Melothria scabra

About 10 to 15 years ago, no one I knew had a clue what a Mexican sour gherkin was.

If you had asked how to grow mouse melon, cucamelon, or sour cucumber, you might have gotten some strange looks. So, naturally, as soon as I saw some available in a seed sharing group, I offered to trade for them.

Gardeners are nothing if not adventurous.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Without a doubt, these odd little grape-sized members of the gourd family were one of my absolute favorite crops to grow. After growing them twice, I learned quite a bit about them, and I’m happy to share it all.

Come and learn how to plant, grow, and care for cucamelons aka Mexican sour gherkins! Here’s what I’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

There are so many boutique crops that pass in and out of fashion that sometimes, it can be tough to keep up.

Many of them are interesting to gardeners who are tired of producing the same old thing, year after year. Sometimes they fall out of fashion because of low yields, or it takes a great deal of work to grow them in regions outside their native territory.

Often, these crops are a food source common to other cultures, in places where they’ve been cultivated and eaten for centuries.

Such is the case with the Mexican sour gherkin, which has persisted as a favorite for many home gardeners for years now.

What Are Cucamelons?

Mouse melons, cucamelons, or sour gherkins, are a species belonging to the Melothria genus. This group is a part of the Cucurbitaceae family, which also includes plants like cucumbers, gourds, and squash.

Sour gherkin, or M. scabra, is a species that is native to the Americas and most commonly found in Central America.

Other similar species can be found growing in the wild throughout North, Central, and South America, and the West Indies. Some have naturalized in other regions.

It’s extremely important to make a distinction between M. scabra and other species like M. pendula and M. charantia.

These species bear a strong resemblance when the fruits they produce are immature, but as the fruits of M. charantia and M. pendula mature and ripen, they turn black.

After they’ve darkened in color, they’re toxic, and should not be ingested. Fruits of M. scabra, however, are edible at any stage. Always confirm the species prior to eating to be sure it’s safe.

In their native region, these creeping vines are typically found in forested areas or along their margins, growing with the support of surrounding plants. They prefer loamy soil, but have been found growing in sandy, lean, or wet conditions as well.

Anatomy

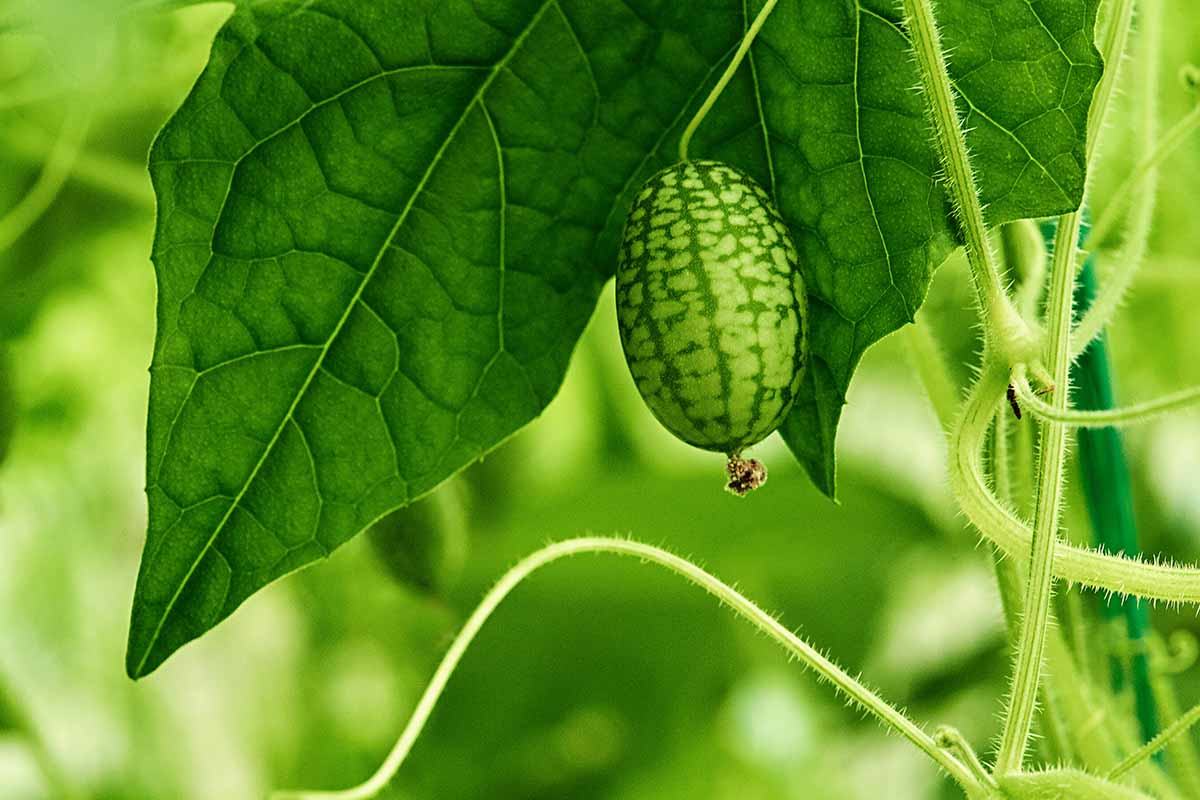

Foliage of this species is much like that of a gourd or cucumber. Their long, fuzzy vines and leaves are almost identical to those of cucumbers, with tendrils that help them to climb and cling to surrounding structures.

Blooms appear in spring and summer with the female blossoms opening first, unlike most Cucurbitaceae species. The blossoms are yellow and five-petaled with a dimple in the center of each.

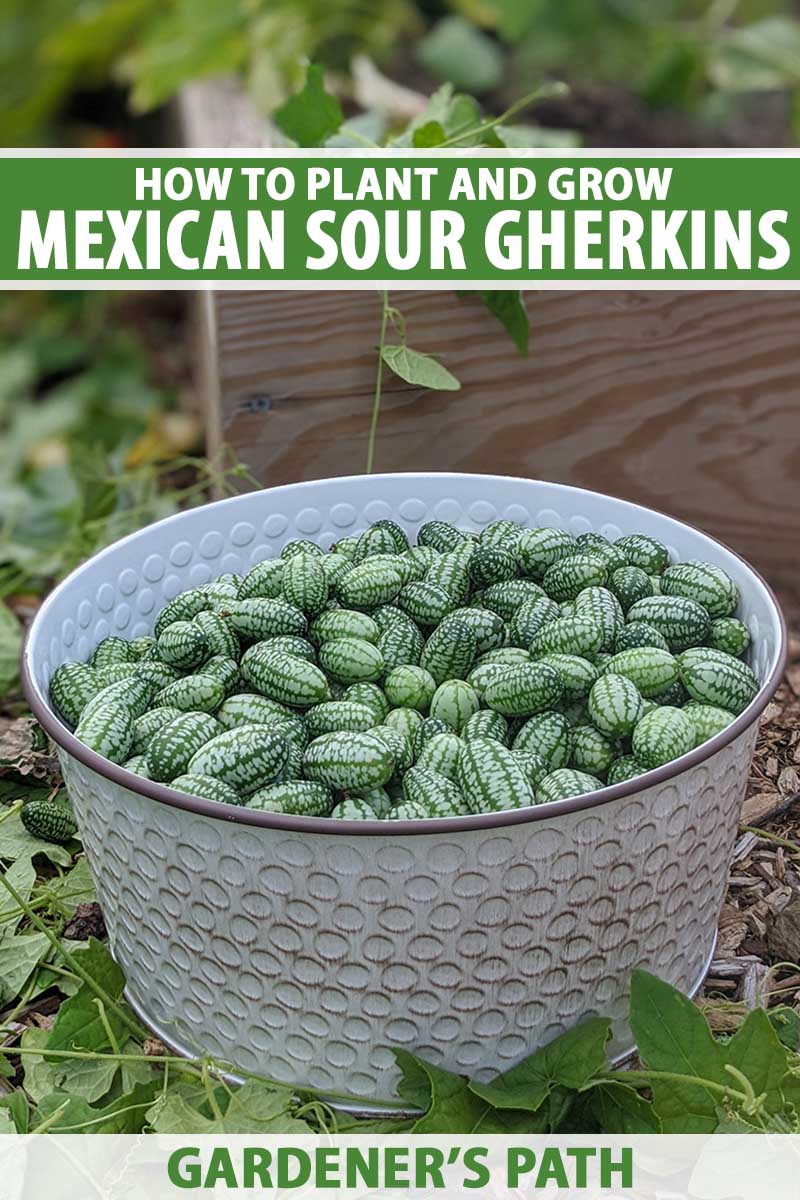

The biggest distinction between cucamelons and their cousins comes from the fruits, which are classified as berries. They range in size from three-quarters of an inch to an inch and a half in length and have a green and white striped pattern akin to a tiny watermelon.

On the interior, the fruits hold soft, teardrop-shaped seeds inside crisp white flesh. Their flavor is much like cucumber, although there is a slight tang that is often described as being lime-like.

Underground, the vines sprout from roots that develop small tubers as they mature.

In regions where temperatures remain above freezing throughout the year, cucamelon plants are perennial and may produce all year long. In cooler regions, the tubers will need protection to return in the spring.

They can also be replanted each year rather than protecting or storing the tubers, and grown as annuals.

Vines can reach 10 to 12 feet or more in length and need support to grow and produce.

Fruits are produced from summer through fall, usually until first frost, and any that are left on the vine after they reach maturity will continue to ripen and fall off on their own. Those that do can be collected for seed.

As I mentioned, these tasty little watermelon wannabes have been cultivated and eaten for centuries by Mesoamericans. Let’s discuss that a bit more.

Cultivation and History

Cucurbit crops have been in cultivation for more than 11,000 years.

Many useful, nutritious crops were cultivated and passed down by the Aztec people and other Indigenous groups in Central America long before they were chronicled in documented history.

The Mexican sour gherkin is but one of those species, which has been referred to by common names including sandiita, or “little watermelon,” and sandia de raton, or “mouse melon,” for centuries by the peoples of the region.

Many cucurbits have a bitter flavor that most people don’t prefer, and this is one reason why cucamelons are so popular – their flavor is sweet and mild.

In the mid-1800s, the plant was described in one of the first known written records by Charles Victor Naudin, a French botanist.

Carl Linnaeus also had a hand in naming the species, although there is some debate about how the name was derived. It wasn’t until the mid-1980s that the term “cucamelon” came about.

Members of Indigenous groups used the fruits as a food source, adding them whole or chopped to mixed salads and stir-frying them to be served with fish and other meats. They were also fed to livestock and eaten fresh from the vine.

Today, they can be used in the same ways and are popular for pickling as well. Their tiny proportions are perfect for packing into a jar for pressure canning with vinegar and spices.

USDA Hardiness Zones 2 to 11 are suitable for growing cucamelons; however, they won’t make it through the winter north of Zone 7 without protection from hard freezes. We’ll cover winterizing in the Maintenance section below.

As the fruits mature, beyond peak harvest, they’ll begin falling from the vine on their own.

For seed saving, they should be left to cure for one to two weeks longer in a cool, dry place and then the seeds can be scooped out and fermented before saving or sowing.

Propagation is easy and fun, and we’re going to cover that next.

Propagation of Cucamelon Plants

Cucamelons should be direct-sown outdoors. Wait to plant until the danger of frost has passed and temperatures in the evening are at least 40ﹾF. Warmer ground typically results in faster germination.

Choose a site with rich, loamy soil and full sun. Be aware that any structure or plant nearby can become a volunteer trellis, so keep the planting site separated from delicate specimens.

It’s not recommended to start these seeds indoors, for two reasons.

First, the roots of most cucurbits don’t like to be touched or disturbed. Secondly, seedlings of this variety are very, very delicate and they don’t transplant well, especially if they need to be hardened off.

From Seed

Start seeds outdoors in early to mid-spring after the danger of frost has passed.

Begin by roughing the soil at the planting site by raking or tilling to loosen it up. Water it enough to moisten it but make sure any excess water drains off.

Mound the soil at 24-inch intervals and plant one to two seeds per mound, inserting them about a quarter to a half an inch deep, pointed side down. Cover them and give the soil a gentle press to settle them in.

If overnight temperatures are still cool, you can use a dome cover to create a microclimate that will insulate the seedlings, such as these garden cloches that are available in a pack of 10 from Amazon.

Cloches can be used until temperatures warm but should be removed on sunny, hot, or humid days, as they can cause wilting.

Be sure to keep the vent open as it gets warmer outside and remove the covers when evening temperatures are at least 50ﹾF minimum, or the seedlings develop their first tendrils.

Germination can occur within seven days to two weeks, depending on the ground temperature. Keep the moisture level consistent by checking the soil surface daily. In the absence of rain, it’s best to offer about one inch of water per week.

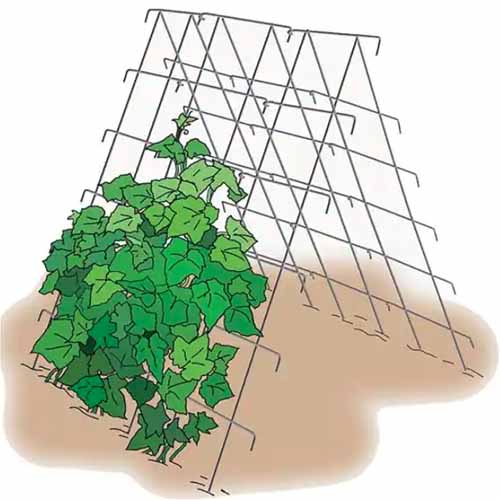

The site you choose should have a structure for the plants to climb on, which should be installed when they’re under about four inches in height. Tendrils form early and are eager to latch on.

A support structure should be able to hold several pounds per vine, although they’re not as heavy as most cucurbits due to the petite size of the fruits.

Container-growing is also an option.

Choose a container with drainage holes that offers at least 12 inches of depth and width per plant. This 32-by-18-inch cedar planter from Leisure Season via Home Depot works perfectly for growing two or three plants.

Fill the container with soil rich in organic material, in a ratio of one part soil to one part perlite or coarse silica sand, and water it well. Allow the excess moisture to drain off.

Make small mounds spaced 12 to 18 inches apart, and press the seeds about a quarter inch deep. Cover them and press gently to settle them in.

Be sure to add a trellis or other support early on to allow them to grasp and climb.

Transplanting

If you plan to purchase starts – although, I’ve never seen them for sale – look for those that are growing in peat pots.

Make a hole the same width and depth as the pot and drop it in carefully. Cover the pot with soil to the base of the seedling but be very gentle, as they can easily be damaged.

Install supports as early on as possible. Water in well to settle and keep the moisture level consistent for the first few weeks.

How to Grow Mexican Sour Gherkins

The planting site should allow for full sun exposure, with at least six hours of direct sunlight per day. Be sure to keep the surrounding area clear of obstructions that can inhibit sunlight, airflow, or pollinator access.

Soil should be rich and loamy. Mixing in one part compost and one part sand at the planting location will provide the nutrients and drainage they need. Keep the pH between about 6.0 and 6.5 for optimum health.

A trellis or other sturdy support, such as this A-frame cucumber garden growing support from Garden’s Alive via Home Depot, is a good choice. It offers two sides and allows for the fruits to hang down away from the leaves.

Gardens Alive Cucumber Growing Support

Guide the vines toward the trellis and gently weave them through and around it to get them started. Once they have a hold of it, it may still be necessary to occasionally guide errant vines back on track.

Don’t allow the vines to trail along the ground as this can invite pests such as slugs and snails, and leave them susceptible to damage from being trampled.

Offer about one inch of water per week in the absence of rain. Cucamelons are rather drought tolerant once established, except in the warmest zones.

While they are able to withstand the heat of summer, in the hottest regions where the heat lasts all day, they will prefer some partial shade.

Mexican sour gherkins can be potted and grown in containers as well, as described above. So if you’d rather add them to a porch or patio garden, that is an option.

Adding fertilizer is optional, although the vines will benefit from an application of two to four inches of well-rotted compost in early spring and midsummer. Be sure to avoid piling the compost against the stems.

If you have poor soil or want to give your vines a boost, a light application of fertilizer doesn’t hurt.

Try using a balanced blend such as Espoma Organic Garden-Tone Herb and Vegetable Food, which is available in eight- or 27-pound bags from Home Depot.

Apply packaged fertilizers according to their printed instructions and make sure to water in well to prevent a buildup of mineral salts.

Growing Tips

- Grow mouse melons in a sunny location where they’ll receive at least six hours of direct light per day.

- Provide support from the time vines are four to six inches in height to give them something to climb.

- Avoid allowing vines to trail on the ground as they may be damaged or attract pests.

- Underground tubers can be left to regrow in warm regions, or dug up and stored over the winter in cooler regions.

Maintenance

No matter if you start in-ground or in a planter, if you plan to grow cucamelons as perennials, they’ll need winter protection in some regions.

As I mentioned, sour gherkins can be grown throughout Hardiness Zones 2 to 11, although they’ll need winter protection from Zone 7 north.

Gardeners in regions that don’t experience hard ground freezing can cut the foliage back to ground level in late fall and mulch with four to six inches of shredded bark or straw.

Just be sure to clear the way in springtime by moving the mulch aside so the new sprouts can emerge.

Areas where hard freezes are common require cutting the vines back to the ground in late fall, just after the first frost, and lifting the tubers for storage.

It may be necessary to dig around to find all of them but do so gently, as they’re not as tough as potatoes. Dig the tubers up, rinse them off, and allow them to dry for a few hours in a cool, dry place to prevent rotting in storage.

Prepare a large paper bag or container with a few cups of coconut coir and place a few tubers on top. Add another layer of coconut coir and tubers, repeating until all of them are covered.

Fold the top of the bag over loosely and place it in an unheated but sheltered location such as the garage or basement to await replanting in the spring.

After the last frost date in your region, prepare the ground or a container as described in the How to Grow section above. Bring the tubers out of storage and allow them to warm to the outside temperature.

Carefully remove them from the substrate and soak them in warm water for about 30 minutes to rehydrate them. This will also signal them to come out of dormancy.

Place the tubers about three inches deep in the soil so the crown is no more than one inch below the surface, and cover them over. Water them in well and they should sprout within seven to 14 days.

Where to Buy Cucamelon Seeds

At this time, only the species plant is available for sale – no commercially available cultivars have been developed.

Cucamelon seeds are open pollinated heirlooms that produce true to the parent, which means they can be harvested at the end of each season as well.

It takes 60 to 70 days to reach maturity, and vines can reach 10 feet in length or more in that time. Sturdy support is important, as described above, as is clearing the way for pollinators to reach the blooms.

You can purchase M. scabra seeds in packets of 30 from Burpee.

Managing Pests and Disease

Despite their membership in the Cucurbitaceae family, cucamelons are nearly pest free and very disease resistant. We’ll briefly touch on a few issues to keep an eye out for.

Herbivores

With the exception of the occasional test nibble from a rabbit or squirrel, there are no known herbivores that will defoliate this species.

Just as I type this, I’m sure there’s a squirrel somewhere with plans to the contrary, but as it stands – we’re in the clear!

Insects

Only two common pests are known to bother with these miniature cukes, and we all know and possibly loathe both: the slug and the aphid.

Aphids

I would challenge you to find a growing guide for any common crop that doesn’t mention aphids. They’re practically universal, appearing without warning and sucking the life out of many plants indiscriminately.

The fluid loss isn’t always the killer – sometimes it’s the diseases that are transferred by their piercing mouthparts that cause the most damage.

If you happen to spot signs of infestation, such as stunting, leaf curling, and discoloration, or if you spot the pests, check out our guide to dealing with aphids and take action fast.

Slugs

If you have slugs in your area that are known to visit the garden, they’ll most likely munch on the leaves and fruit of the mouse melon as well.

This is less likely to happen if the vines are trained on a trellis rather than trailing on the ground, but it’s still not impossible.

Learn how to control slugs in our guide.

Disease

With such a short list of pests of concern, I’m sure you were hoping for the same with diseases. Sorry to disappoint, but there are a few to be wary of with sour gherkins.

Cucumber Mosaic Virus

Among botanical diseases, mosaic viruses are some of the most damaging maladies that can befall a crop.

They also infect the widest range of host species, with over one thousand known fruits, vegetables, and ornamentals affected by various types of mosaic viruses.

Cucumber mosaic virus is caused by several different Cucumovirus pathogens, and is characterized by leaf mottling, growth distortions and stunting, and deformities of the fruit.

Typically, viruses such as these are passed from host to host via the feeding mouthparts of insects such as aphids.

When they pierce tissues to feed from the sap on the interior, they infect the plant with the virus at the same time. This can cause widespread damage.

Unfortunately, there is no cure for mosaic virus and affected plants will need to be removed and destroyed. Never compost them, and be sure that you don’t save seeds from them either, as seeds can be carriers of viral pathogens.

Powdery Mildew

Powdery mildew is a pain. There are hundreds of fungal pathogens that can cause it and it can show up on thousands of different plants.

Learn how to deal with powdery mildew naturally in our comprehensive guide.

Harvesting Cucamelon Fruit

It’s easy and fun to harvest cucamelons!

Throughout the summer, new fruit is set continuously. Be sure to check daily since they only take a couple days to mature. They can also be rather sneaky and hide behind the large leaves.

They’re picked in the same way as cucumbers, with one exception – the vines can be rather delicate, so it’s best to either snip ripe cucamelons off with clean shears or hold the stem and twist each one free.

The best way to tell if they’re ripe is to monitor their size. Pollinated female flowers will drop their petals and the ovary will begin to plump in the same day. In my own experience, they may be the size of a grape and ready to eat within the next day or two!

As they continue to mature and ripen, they tend to lose firmness as the seeds inside fill out.

Any that you don’t pick within about a week from when they start developing are better left to ripen fully if you plan to collect seed. Otherwise, you can pick any that are past their peak and toss them on the compost pile.

Store harvested fruit in the refrigerator for up to two weeks if you don’t plan to eat it right away.

Preserving Mexican Sour Gherkins

These Lilliputian cukes are the perfect picklers!

Rinse your harvest off and pat them dry. Add them to a canning jar, fill with your choice of brine made with vinegar, salt, and spices, and pressure can them for delectable pickles to enjoy all year long.

If your pickling skills are underdeveloped, take a look at this expert article from our sister site, Foodal, to learn all about how it’s done.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Sour gherkins can be used in the same ways as you’d use cucumbers. They’re delectable when eaten raw, or they can be split down the middle and tossed into salads. Or, leave them whole if you prefer – no peeling or seeding necessary.

For a cooked veggie side, split the cucamelons in half, toss them in a pan with butter or oil, and saute to your liking. It only takes a couple of minutes, and they make a wonderful accompaniment to fish or chicken.

Quarter them and place them on some foil or a grill-safe tray, and add butter, salt, and a pinch of red chili flakes. Grill them for just a few minutes until they start to release their juices and serve them as a relish with grilled pork chops or salmon.

They blend flawlessly with tomatoes, garlic, and oil for a refreshing bruschetta topping as well.

My mouth is watering just thinking about it!

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Herbaceous vining perennial | Water Needs: | Moderate |

| Native to: | Central America and the West Indies | Tolerance: | Some drought and heat |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 2-11 | Maintenance: | Low |

| Season: | Summer | Soil Type: | Loamy, sandy loam |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil pH: | 6.0-6.5 |

| Time to Maturity: | 60-70 days | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 18 inches | Companion Planting: | Carrots, onions, oregano, parsnips, radishes |

| Planting Depth: | 1/4 inch (seeds); 3 inches (tubers) | Avoid Planting With: | Tomatoes, potatoes |

| Height: | 10-12 feet | Family: | Cucurbitaceae |

| Spread: | 2-4 feet | Genus: | Melothria |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, slugs; cucumber mosaic virus, powdery mildew | Species: | Scabra |

Mighty Mouse Melons or Quirky Cukes?

My kids and I love cucumbers, so each year, I always planted several extra vines to make sure we would have enough for pickling and preserving as well as eating fresh.

Once I found this adorable, quirky alternative, it became a staple in our garden plan too.

Will you be giving cucamelons a try? We’d love to see your setup and hear about your harvest – whether it was fantastic or frustrating. We can help with troubleshooting too, so leave us your comments and questions below!

If you’re shopping for some more cucurbit crops to add variety to your harvest, check these guides out next:

I am in Pretoria in South Africa. I successfully managed to grow cucamelon plants and have 200 ready to be sold. It’s quite a satisfying hobby and hope to grow a thousand in 2023 for sale.