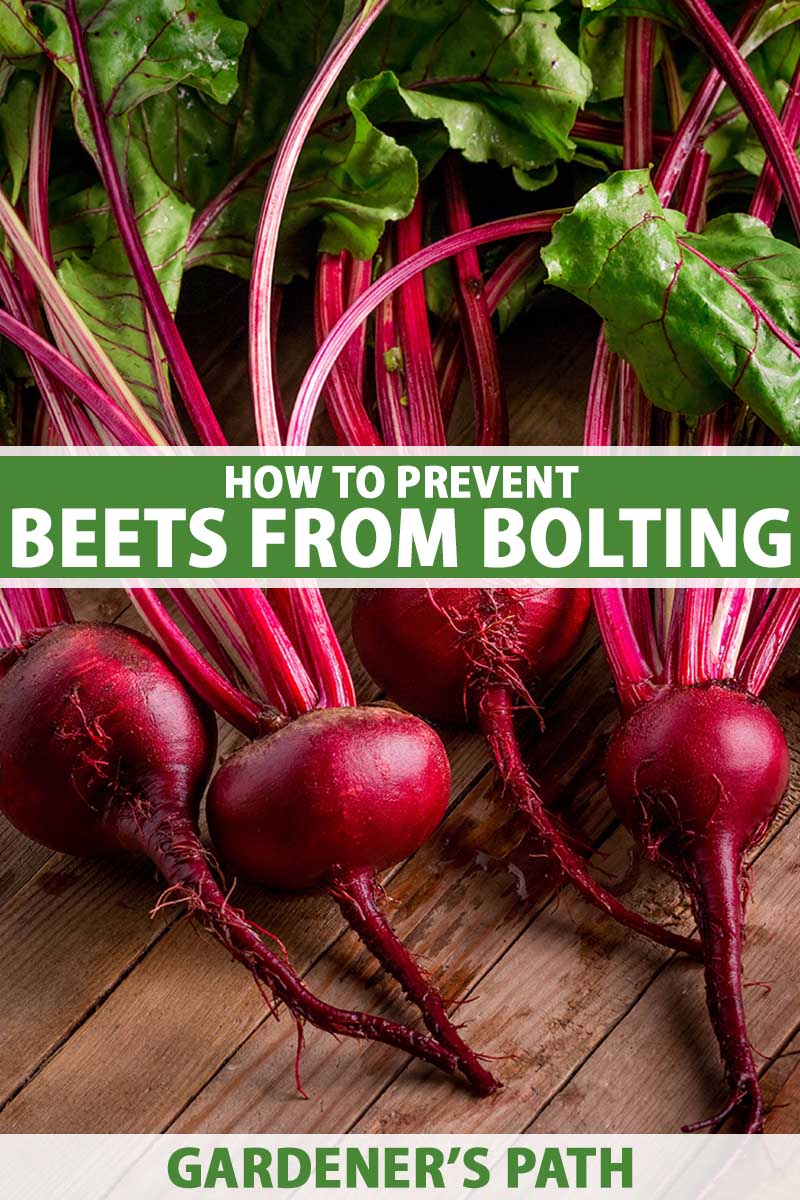

Everything about beets (Beta vulgaris) makes me happy – from soaking those funky-looking seeds and setting them in the ground to lifting the robust globes of earthy goodness from the garden.

After planting, I’ve kept pests away from the foliage and stayed vigilant against diseases. Now, it’s just a case of waiting for the roots to develop.

The only thing standing between me and a goat cheese and beet salad? Bolting.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Bolting is caused by stress. You and I might have a panic attack, stress eat, or scroll mindlessly through social media when we’re stressed. Plants send out flowers.

Seems like a healthier reaction to stress to me, but bolting can mean that you won’t be able to enjoy your delicious beets. When a plant bolts, the leaves turn bitter and the roots become woody.

So, what can a gardener do about it? There are preventative measures you can take and, if all else fails, you might just have to enjoy your roots or beet leaves early.

Here are all the things we’ll chat about in the coming guide:

What You’ll Learn

First things first. We need to discuss why this phenomenon occurs.

Why Do Beets Bolt?

“Bolting” refers to the plant sending out flowers prematurely – at a time when we gardeners don’t want them to.

In the normal course of events, B. vulgaris flowers in their second year, as they are biennials,, which means they complete their life cycle in two years. Annuals take one year to complete their life cycle, and perennials require three or more years.

After the first year, beets send out flowers, which turn into seeds and then the plant dies. But those seeds carry their genetic material and become new beets.

Sometimes, beets will grow flowers in their first year of life. This is what growers refer to as bolting, and it usually happens as the result of stress.

Flowering is influenced by daylight hours, temperature, and other factors like water availability.

These elements influence the hormonal balance in the plant, suppressing some hormones and increasing others. In the normal course of events, the plant will put its energy into developing a big, healthy root, stalks, and leaves during the first year of its life.

But if something goes wrong, the plant enters a kind of emergency mode and sends out flowers and subsequent seeds as a means of reproducing. It is acting in its own best interests to ensure its genetic material survives in the face of some kind of stressor.

It’s not in the best interest of us gardeners, though, because once B. vulgaris bolts the root turns woody and the leaves become bitter and inedible.

You can learn more about bolting in our guide.

What Causes Bolting

If you wanted to create the perfect environment for your beets to bolt, here’s what you would do:

First, give the young plants a nice long period of cool weather with extra moist soil. Then, provide it with long days filled with heat and very little water. Voila!

B. vulgaris needs consistent, even moisture and protection from extreme temperature fluctuations.

Technically, the process of getting ready to flower in beets is known as vernalization. It happens naturally when the plants are exposed to prolonged cold.

The plant emerges in the spring to cool temperatures and short days, which gradually shift to longer and warmer days.

Seeds and seedlings need about five weeks between 41 to 48°F to vernalize. If seeds still on the plant from the previous year or in the ground after falling off are exposed to these temperatures for long enough, they will be vernalized.

Once a plant or seed has vernalized, it’s capable of producing flowers.

If temperatures become too hot – over 65°F or so – depending on the number of daylight hours, the plant might become stressed enough to send out those flowers and complete the lifecycle earlier than it typically would.

Similarly, if it has been consistently cloudy and suddenly the weather changes to nonstop sun every day, that can also cause bolting.

Another common cause is setting out transplants too early, if the seedlings are exposed to a sudden drop in temperature, especially when combined with a lack of water.

Overfertilization with nitrogen, low soil fertility, and inconsistent moisture are the other culprits.

Once the veggie bolts, the sugar content of the root is reduced, and it turns hard and woody. The leaves also become tough and bitter at this point as well.

Beets tend to bolt more readily than some other species because they vernalize with a short period of cool temperatures. Some species require a long period to vernalize.

When bolting occurs, you’ll start to see flower stalks grow up out of the ground and rapidly develop insignificant blooms followed by seed pods.

How to Prevent Bolting

Because bolting is largely weather-dependent, there isn’t a lot you can do to control it.

If the weather takes a warm turn, it can help to put some shade cloth over the planting area. This will reduce the temperature during the worst of the heat.

Other than that, the best you can do is to maintain consistent soil moisture. Beets need a good amount of water as they develop, so try to keep the soil moist but not wet at all times.

If you’ve ever hand-washed some dishes with a sponge and you wring out that sponge well when you’re done, that’s the texture you’re aiming for. Not soggy wet, and not dry.

Don’t plant too early in the spring, and if temperatures drop below 45°F, make sure the plants have enough water.

What To Do If Your Plant Bolts

Once B. vulgaris bolts, there’s nothing you can do to fix it. You can snip off the flower stem, but that won’t stop the plant from otherwise completing the lifecycle process.

Just because you removed the flowers, that doesn’t mean the root isn’t still going to shift the sugar content and toughen up the leaves.

Your best bet is to harvest the beetroots right away. If you catch it early enough, the roots will still taste just fine.

If the roots are far too immature to eat, you can always enjoy the leaves if you catch the bolting plant quickly enough. They’re pretty much the same as chard, anyway.

Don’t Stress

Nothing should dare get between my beet soup, salad, and roasted veggies. Not even bolting.

I’ve been known to dash outside with some shade cloth and obsessively monitor the soil moisture.

Even though beets are fairly quick and easy to grow, I’m not letting anything threaten my harvest.

So, what seems to be causing the problem on your plants? Did you have a cool spring that jumped into a hot summer? Did the soil dry out for too long? Let us know what you’re experiencing in the comments.

Now that the bolting situation is under control, there’s more to know about making the most out of this root vegetable.

If you found this guide helpful, and I hope you did, these beet guides might also be useful for you: