Prunus laurocerasus

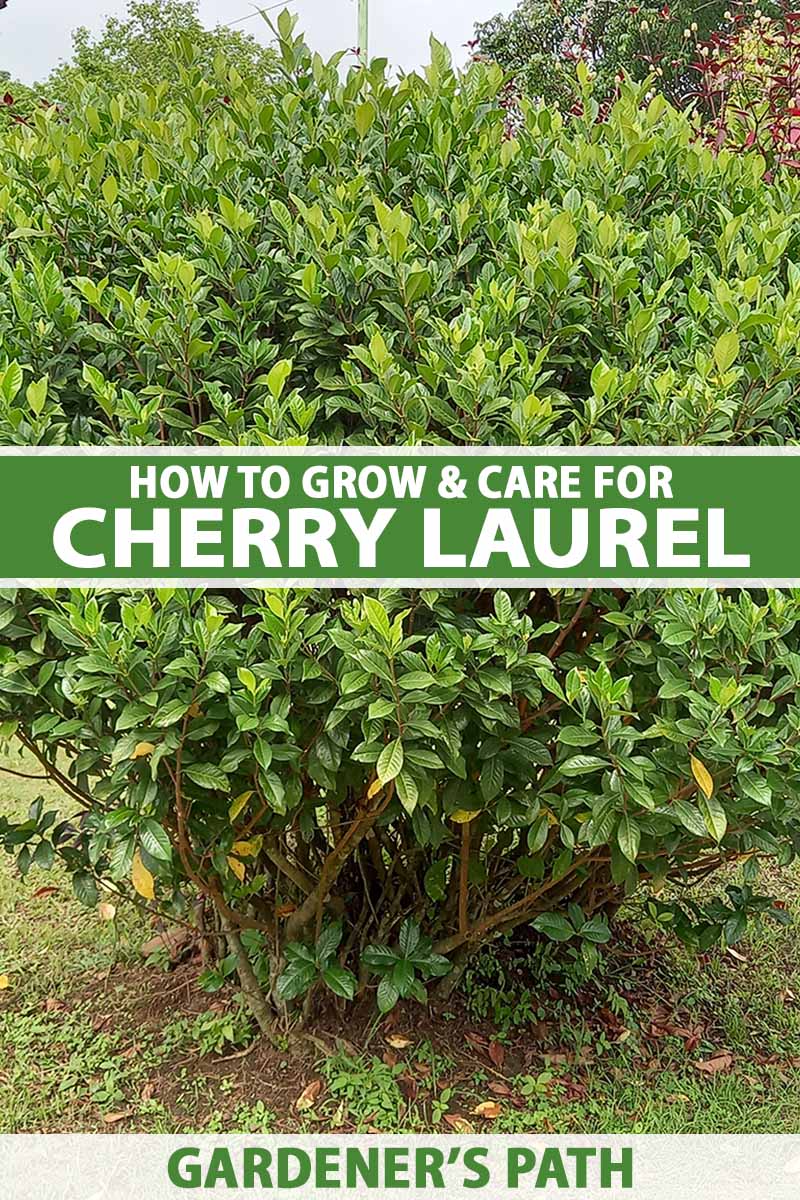

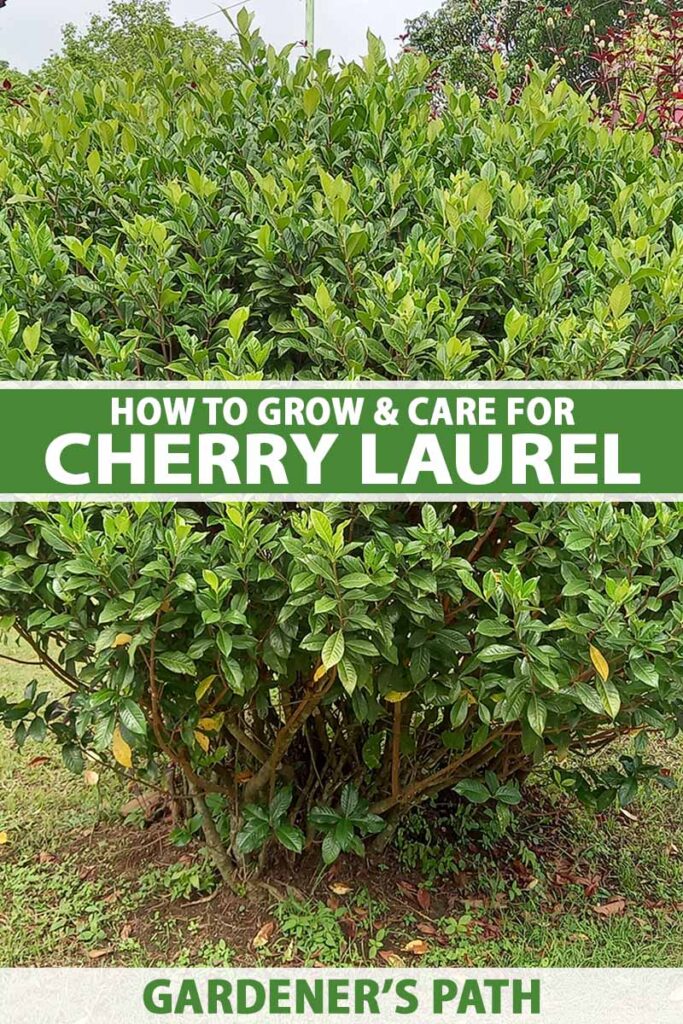

In the world of landscape design, it’s hard to go wrong with a heap of green shrubbery. And when that shrubbery is none other than a cherry laurel, it just feels oh so right.

The glossy green broadleaf foliage is alluring, what with the way that it grows all dense and tightly-packed.

Yet each leaf can be admired individually, as they’re of ample size. They’re also evergreen, meaning they’ll provide a year-round spectacle.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

But let’s not forget the flowers and ornamental fruits, each of which deserves an eyeful of aesthetic admiration.

Add attractiveness to wildlife and some cultural toughness to the mix, and you’ve got yourself a real winner.

Ready to start on your cherry laurel journey? This guide will show you how.

Here’s what we’ll be discussing:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Cherry Laurel Shrubs?

A member of the Rosaceae family, Prunus laurocerasus is a stunning evergreen shrub that originates in southeastern Europe and Asia Minor.

Hardy in USDA Zones 6 to 8, cherry laurels typically reach mature heights of 10 to 20 feet, with spreads of about 20 to 30 feet.

Although these multi-stemmed plants are typically grown as shrubs in the landscape, they can also be pruned to look like low-branching trees.

P. laurocerasus boasts densely-packed, medium to dark green foliage that’s glossy up top and a bit pale and matte underneath.

Individual leaves are usually two to six inches long, each with an oblong to elliptical shape.

Come spring, white flower clusters emerge from light green buds.

Growing two to five inches long, each is made up of many small, five-petaled, and botanically perfect flowers, i.e. these bear both male and female parts.

The fragrant blooms attract insect pollinators such as bees and butterflies.

By midsummer, the blooms give way to small, rounded, purple to black drupes, which are quite tasty to birds. Within each fruit lies a round, tan seed that ripens in fall.

But before you get any ideas, you should know that the entirety of a cherry laurel shrub contains cyanogenic glycosides such as amygdalin, the leaves and seeds especially.

These are not edible. If ingested, you could develop a grab bag of possible symptoms such as weakness, convulsions, shock, and respiratory failure.

Therefore, I wouldn’t recommend that you, your pets, or your livestock go snacking on a cherry laurel.

Cultivation and History

Before we dive into P. laurocerasus any further, let’s examine its name.

Prunus originates from the Latin prunum, meaning “plum” – another member of the Prunus genus. The species name laurocerasus comes from the Latin words “cerasus” and “laurus” for “cherry” and “laurel,” hence the common name.

Beyond its native lands, the cherry laurel was all but unknown for a long time.

That is, until sometime in the mid-16th century, when a traveler to Genoa, Italy established some specimens in a local garden.

P. laurocerasus was introduced into Northern Europe around the year 1576 CE, thanks to the horticulturally influential Carolus Clusius.

This Flemish botanist and doctor – the man responsible for bringing many significant plants to Europe, from the tulip to the potato – received a dying cherry laurel from Constantinople, revitalized it, and made yet another mark on the horticultural world.

By the mid-1600s, P. laurocerasus had become a popular choice for espalier in estate gardens.

Come 1730 CE, it had become more trendy to let cherry laurel groupings grow a bit more wild and untamed. Throughout this time, its popularity in England earned the plant its “English laurel” moniker.

P. laurocerasus soon found a non-ornamental application: a foliar extract, dubbed “laurel water,” was used to add a delightful almond-y essence to various foods and drinks.

Unfortunately, this aroma was due to the presence of hydrogen cyanide, which led to a few high-profile poisonings in the 1700s. After that, the extract’s culinary appeal understandably vanished.

The shrub has since been introduced to North America, where it has surfed the ups and downs of ornamental landscaping trends. But for the most part, it’s a beloved shrub. For the most part…

It’s worth mentioning that this shrub has some invasive tendencies.

Its seeds are spread far and wide by birds, it vegetatively spreads via suckering, and its cultural requirements, while making it easy to cultivate, can also make it hard to kill.

All of this could potentially displace native species as well, so it’s best to always double-check your local laws and invasive plant lists prior to planting.

If you’re located in the Pacific Northwest, you should take particular heed.

The plant is on Washington’s monitor list, which keeps tabs on suspected noxious weeds, while the Native Plant Society of Oregon has P. laurocerasus listed as a medium- to high-impact species in terms of its effect on native habitats, alteration of ecological functions, and tendency to form monocultures.

Cherry Laurel Propagation

Do you want to propagate some cherry laurels? The best means of doing so are from seed, cuttings, or via transplanting.

From Seed

To gather seeds, collect ripe fruits in the fall. Remove the pulpy drupe from around the seeds, and leave the seeds out to dry.

Alternatively, you could purchase seeds from a reputable vendor and skip all of that harvesting nonsense.

Once you have your seeds, let them soak in water for 24 hours to scarify them.

After that, place the seeds in a baggie of moist sand before leaving said baggie in the refrigerator for 60 to 90 days. Make sure to keep the sand moist all the while!

Once your seeds are stratified, remove them from their sandy baggie. Carefully, though – it’s likely that the radicals may have already emerged.

Sow the seeds an inch deep into a 50:50 mix of peat moss and perlite, whether in a seed tray or individual three-inch containers.

Moisten the media and expose them to bright, indirect light indoors, ensuring that the media is kept continuously moist.

After the final frost in spring, the seedlings should be ready for direct sowing outside.

But first, harden off the seedlings by leaving them outdoors for 30 to 60 minutes before bringing them back inside. Add a half to a full hour of exposure each day, until they can handle a full day of being outdoors.

At this point, the seedlings can go in the ground, whether into a seedling bed or their forever homes.

Alternatively, you could grow them in outdoor containers, at least until they outgrow five-gallon ones that are easy to maintain.

From Cuttings

If genetic variation isn’t your thing, then rooting cuttings is the propagation method for you! This allows you to create clones of the parent plant.

Come summer, take four- to six-inch cuttings from healthy-looking shoots with a sharp and sterile blade.

Make the actual cuts just below a node, defoliate the bottom two inches of each cutting, and dip the de-leafed sections in a rooting hormone, such as this Bonide-brand IBA powder from Arbico Organics.

Bonide Bontone II Powdered Rooting Hormone

Stick each cutting into its own three-inch container filled with a 50:50 mix of peat moss and sand.

Water it in, and place the containers somewhere indoors where they will receive bright, indirect light, such as on a windowsill.

After eight weeks of light exposure and constant moisture, the cuttings should be well and truly rooted.

At this point, you can transplant them directly in-ground or into outdoor containers. But make sure to harden them off first, using the above protocol.

From Seedlings/Transplanting

Prepare well-draining, fertile soil with a pH of 5.0 to 7.0. Exposure-wise, these plants can handle full sun, full shade, and everything in between.

A good idea would be to try and balance light and climate – specimens in USDA Zone 6 should receive more sun, while those in Zone 8 could probably use some more shade.

Space these sites are about as far apart as your specimens are expected to spread at maturity. Container-grown transplants should have at least an inch or two of elbow room between the roots and the container’s sides.

Dig holes about as deep and a bit wider than the transplants’ root systems.

For some added fertility, feel free to mix the dug-out soil with some organic matter such as compost or rotted manure prior to backfilling.

Once the transplants are in their holes, alternate backfilling with watering until transplanting is complete. At this point, pat yourself on the back – ya done did it!

How to Grow Cherry Laurel Shrubs

Now that you’ve got a cherry laurel or two in the ground, let’s discuss how to keep them happy throughout their stay in your garden.

Climate and Exposure Needs

P. laurocerasus has a fairly narrow hardiness range: USDA Zones 6 to 8.

But within these zones, the sky’s the limit in terms of placement options. These shrubs can handle full sun to full shade, salt spray, wind, and even atmospheric pollution!

For optimal growth, try to hit an equilibrium of sorts with the light and climate. Warmer Zone, less light. Cooler Zone, more light.

Soil Needs

Rich fertility, a high drainage capacity, and an acidic to neutral pH are solid ingredients for the ideal cherry laurel soil. Specifically, a pH range of 5.0 to 7.0 works quite nicely.

As for the soil nutrients, working an inch or two of organic matter into the root zone every spring goes a long way.

Water and Fertilizer Needs

A cherry laurel prefers to sit in moist soils. Therefore, you should water whenever the soil feels dry about three inches down. For an approximation, a finger’s length should suffice.

A springtime addition of supplemental fertilizer for acid-loving evergreens would be helpful as well.

Try this continuous-release liquid fertilizer from Scotts, available from Amazon.

Growing Tips

- Provide full sun to full shade exposure, and adjust based on USDA Hardiness Zone.

- Ensure that the soil is well-draining.

- A cherry laurel prefers constant soil moisture around the roots.

Pruning and Maintenance

The evergreen leaves of a cherry laurel don’t exhibit the autumnal color change and mass fall that deciduous ones do.

But broadleaf evergreens such as P. laurocerasus do cyclically drop their oldest leaves each year, so you may want to rake those up as desired.

Additionally, maintaining a couple inches of mulch above the root zone will help to retain moisture while also suppressing weed growth.

Depending on the desired shape, you can prune your cherry laurels in many different ways.

A controlled shearing, keeping it low and spreading like a bushy ground cover, shaping it to be tall and treelike… you have options.

Save this big, shape-altering pruning session for early spring, and feel free to go nuts – these plants can tolerate heavy pruning.

Dead, dying, and/or diseased branches should be removed ASAP, whenever you happen to notice them.

And make sure to promptly prune away suckers, too, so that your shrubs don’t expand out of bounds.

Cherry Laurel Cultivars to Select

A standard P. laurocerasus is fantastic, and can be purchased from Nature Hills Nursery.

But cherry laurel cultivars definitely have their merits, as well. Here’s a handful of varieties that you may like.

Otto Luyken

Introduced by Hesse Nurseries in Germany circa 1968, ‘Otto Luyken’ is a pretty compact cultivar, attaining a height of three to four feet and spread of six to eight feet.

Eventually, older plants may attain heights of six to 10 feet in ideal conditions.

This variety is also free-flowering, meaning its bloom time is longer and less limited to a certain period of time.

In a bloomless pinch, you can distinguish it from other cherry laurels by examining the leaves – they’ll point more upward, often at a 45- to a 60-degree angle. How’s that for variety?

Schipkaensis

Another hard-to-pronounce cultivar, ‘Schipkaensis’ is well worth learning the phonetics of. Either that, or you can refer to it by its nickname, “skip laurel.”

Back in 1889, ‘Schipkaensis’ was discovered near the Bulgarian Shipka Pass, growing at an elevation of 4,000 feet.

As you can imagine, it’s quite tough, with an extended hardiness range of USDA Zones 5 to 8.

With a mature height of about four to five feet, the leaves of this variety are a bit narrower than those of the species plant.

You definitely don’t want to “skip” the skip laurel. For a ready-to-plant specimen, visit FastGrowingTrees.com.

Zabeliana

Speaking of narrow foliage, the leaves of ‘Zabeliana’ are quite skinny, practically willow-like.

The habit of this one is especially low and wide-spreading, with heights of three to five feet and spreads of 12 to 25 feet when fully grown.

Another free-flowerer, ‘Zabeliana’ is a low-growing bloomer that any gardener would enjoy.

Managing Pests and Disease

Cherry laurels do attract wildlife, but most animals don’t give these plants any trouble.

A deer-resistant shrub, P. laurocerasus doesn’t have to deal with many pests and diseases. But the problems that it can suffer from are well worth knowing about.

Proper cultivation leaves plants more capable of dealing with health threats, so be sure to grow your cherry laurels properly!

Insects

Bugs aren’t the most sterile of creatures, as they can easily vector diseases while they feed. But that’s the great thing about proper pest management – it can also help to prevent disease!

Peach Tree Borers

Also known as Synanthedon exitiosa, peach tree borers primarily attack species of Prunus in the landscape, cherry laurels in particular.

The wasp-like adults are a steel blue to black in hue, while the larvae have white to pinkish to light brown bodies and darker-colored heads.

After the female adults mate and lay their eggs in summer beneath the bark at plant bases, the larvae hatch and bore their way up into the shrub, leaving reddish-brown frass in their wake.

This feeding continues all the way through fall and winter into spring. Come summer, the larvae pupate into adults, and the cycle continues.

Bored-through tunnels often exhibit gummosis, or an oozing of thick, jelly-like sap.

These tunnels can damage the vascular tissues of the plant, leading to wilt and leaf chlorosis. Young plants can be girdled and killed, while older specimens can usually sustain moderate infestations.

It’s important that you prune and destroy infested branches when you happen to notice them.

If there are only a few larvae present, you can dig them out with a sharp blade or kill them with a wire poked through the feeding tunnels.

White Prunicola Scale

A species of armored scale, Pseudaulacaspis prunicola can be found on the twig and branch bark of infested specimens all year long.

These circular white scale insects puncture and extract vital plant fluids with their piercing-sucking mouthparts, which can cause chlorosis, leaf drop, and stunted growth. If infestations are heavy enough, entire branches could die.

Necrotic branches should be pruned and destroyed. More moderate infestations can be swept off of infested plant surfaces using a brush.

Sprays of horticultural oil or insecticidal soaps can be effective, especially when these pests are in their crawler stage.

To monitor for this stage of the life cycle, wrap some double-sided tape around a branch or two. When you notice crawlers on the tape, you’ve got the green light to make with the spraying.

Need some horticultural oil? Check out Monterey’s ready-to-use spray, available in 32-ounce bottles on Amazon.

Disease

Even though you’re getting your hands dirty with soil and various plant juices, it’s important to garden in a sanitary manner.

This means using sterile tools, disease-free soils, and pathogen-free plant stock. A quality pair of gardening gloves doesn’t hurt either.

Cherry Shot-Hole Disease

Are the leaves of your Prunus species exhibiting round, tiny holes about an eighth of an inch in diameter? If so, you may be dealing with cherry shot-hole disease.

Often caused by the fungus Blumeriella jaapii or the bacterium Xanthomonas pruni, cherry shot-hole disease is prone to occuring in warm and wet springtime conditions.

Symptoms start with brown to reddish-brown leaf spots, which later drop out of the foliage and leave holes behind.

This is mostly a cosmetic issue, and one that’s quickly hidden by the growth of new leaves. But photosynthesis will definitely be hindered some, leading to reduced growth and vigor.

You won’t usually need to do much besides promptly pruning out afflicted leaves and raking up fallen ones – your specimens should recover in time.

You could also improve airflow by pruning the crown, if you desire.

Root Rot

Ah, root rot: the bane of many moisture-loving plants.

Although the roots of cherry laurel love themselves some soil moistness, they also need oxygen.

But when the roots are chronically deprived of O2 thanks to oversaturated soils, they can suffocate and die. And don’t even get me started on the pathogens that overly-wet conditions could encourage!

These rotted roots can cause all sorts of issues above the soil line, from chlorosis to necrosis.

The best way to avoid this problem is to prevent it entirely, so make sure you don’t overwater, and provide well-draining soils!

Cherry Laurel Best Uses

As you can imagine, the aesthetic gifts of a cherry laurel lend this shrub to many landscaping applications.

Its dense foliage makes the shrub a fantastic screen, hedge, or foundation planting. Whether placed together in a grouping or alone as a specimen, P. laurocerasus isn’t picky.

The flowers can attract many pollinating insects to your landscape, while the fruits can draw beautiful birds to feed from and nest within the plant.

And I’ve even heard that the leaves make a solid leafy backdrop for floral arrangements, if that’s your thing.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Broadleaf evergreen woody shrub | Flower/Foliage Color: | White/medium to dark green |

| Native to: | Asia Minor, southeastern Europe | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 6-8 | Tolerance: | Deer, heavy pruning, occasional drought, pollution, salt spray, wind |

| Bloom Time: | Spring | Soil Type: | Fertile |

| Exposure: | Full sun-full shade | Soil pH: | 5.0-7.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | 5-6 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | Width of mature spread | Attracts: | Bees, birds, butterflies |

| Planting Depth: | 1 inch (seeds), depth of root system (transplants) | Uses: | Groupings, hedges, foundation plantings, screens, specimens, wildlife attraction |

| Height: | 10-20 feet | Order: | Rosales |

| Spread: | 20-30 feet | Family: | Rosaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Prunus |

| Common Pests and Disease: | Peach tree borers, white prunicola scale; root rot, cherry shot-hole disease | Species: | Laurocerasus |

Rest on Your (Cherry) Laurels

Metaphorically, that is. Lounging atop a P. laurocerasus would be pretty painful, for both person and plant.

But hey, you’re on your way towards having a cherry laurel in the ground, which is certainly commendable. And after growing and caring for one of these bad boys, you’re sure to love ’em!

Questions? Concerns? All of that and more can go in the comments section below.

In need of other Prunus pointers? Then these guides will definitely be a step in the right direction:

The European Union Regulations 2014/2016 prohibit the sake, growing, distrubition and transportation of invasive plant spices like Cherry Laurel and Rhodedendron plants in Ireland

Thanks for sharing this valuable information, Catherine. As we mention above in the article, it’s always a good idea to research a plant’s tendencies in your local environment before you commit, to avoid planting anything potentially invasive.