Quercus muehlenbergii

Chinkapin oak, Quercus muehlenbergii, is a type of chestnut oak. It belongs to the white oak group of the Fagaceae family of trees that contains beeches, chestnuts, and oaks.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

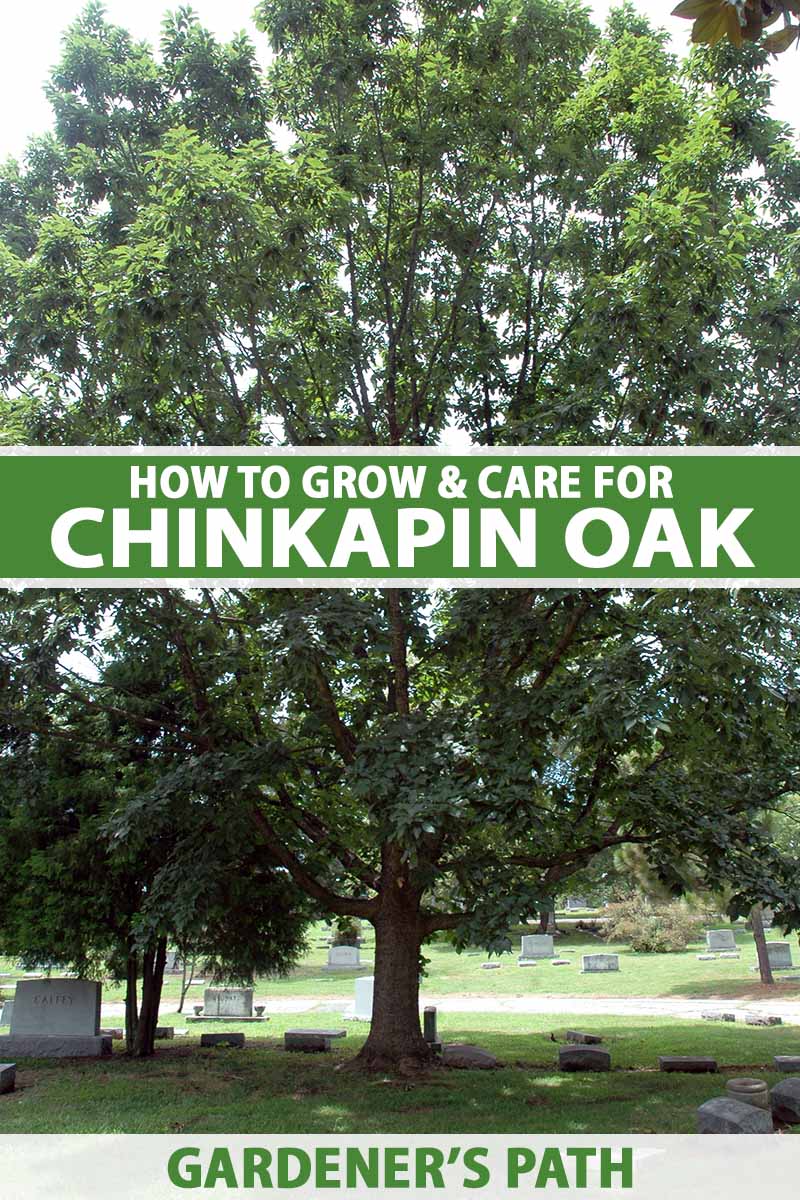

Native to central and eastern North America, it is suited to cultivation in USDA Hardiness Zones 4 to 7, and grows best as a specimen with room to spread its branches and cast pleasant shade for multiple generations to enjoy.

Our guide to growing oak trees provides general cultivation instructions.

In this article, we’ll discuss all you need to know to grow Q. muehlenbergii in your landscape.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

Let’s get to know this tree.

Cultivation and History

Quercus muehlenbergii is not to be confused with three chestnut relatives: the Allegheny, Castanea pumila, Chinese, C. henryi, and Ozark, C. ozarkensis, chinquapin species.

It is a deciduous single-trunk shade tree that grows between 50 and 60 feet tall and wide. The overall shape is like a pyramid or oval when young, becoming rounded as it matures.

The glossy, leathery leaves are narrow and lance-shaped, with irregular, ruffly, coarse-toothed margins and a length of four and a half to six inches.

They are dark green with pale green undersides in the spring and summer, and turn yellow, orange, and brown in the fall. The bark is richly textured with thin scales and grooves that deepen with age.

It grows at a rate of 12 to 24 inches per year. Nondescript greenish male and female flowers are similar to those of a chestnut tree, with male catkins and female spikes.

The female flowers set the fruits or nuts we call acorns. It can take up to 30 years before a tree produces a crop of acorns.

The acorns start green and mature to dark brown. They are edible and have a sweet flavor that attracts local wildlife like birds, deer, foxes, opossums, raccoons, rabbits, rodents, and squirrels.

Acorns do not form every year, but rather every two to five years. An acorn-producing year is called a “mast event.”

In addition to wildlife, some people consume the nuts either roasted or ground into flour, after completing a process of boiling and drying to remove the bitter tannins they contain when raw.

These tannins are potentially toxic when consumed in large quantities.

Can You Eat Acorns?

Some people eat Q. muehlenbergii acorns, but beware: When raw, they contain tannins that taste bitter and can cause gastrointestinal upset.

If you choose to consume acorns, collect only those that have turned brown and have caps attached. Avoid those with blemishes, a green color, holes, missing caps, or soft spots.

Also known as a chinquapin or yellow chestnut oak, the Latin name Q. muehlenbergii honors Gotthilf Heinreich Ernst Muhlenberg.

He was a Lutheran clergyman, botanist, and the namesake of Muhlenberg College in Pennsylvania.

In Algonquian, chinquapin and chinkapin mean “great seed.”

Hard-wearing chinkapin wood has a long history of use in the Ohio River Valley as firewood for steamships, posts and rails for fences, and ties for railroad tracks.

It is not uncommon for Q. muehlenbergii to live over 100 years.

In Oley, Pennsylvania, there is a chinkapin believed to be 500 to 700 years old. Steeped in Native American lore, it is called the “Sacred Oak.”

In nature, Q. muehlenbergii hybridizes readily with other oak species. One is the shrubby dwarf chinkapin oak, Q. prinoides.

Q. × introgressa, the Concordia oak, was a 2015 discovery.

And Deam’s oak, Q. × deamii , is a cross between Q. muehlenbergii and the bur oak, Q. macrocarpa.

Let’s find out how to start a tree in the home landscape.

Propagation

An acorn, as we know, is the seed-containing fruit of an oak.

You may have luck starting with an acorn, but you’ll most likely begin with a nursery pot or a more mature balled sapling with a root mass wrapped in burlap.

Other methods – like rooting stem cuttings and bud grafting – are less likely to result in successful propagation.

Let’s look at how to start with an acorn and a nursery transplant.

From Seed

You can start a tree by sowing seed as soon as it is harvested, or in this case, acorns.

Harvest acorns in the fall and determine their viability by dropping them into a bucket of water. Those that sink are good to plant. Discard those that float.

Lay entire acorns in their shells on their sides. Cover them with three-quarters to an inch of soil. Layer two to three inches of mulch over the soil.

Keep the soil moist but not soggy.

When the acorns sprout, usually in about four to six weeks, remove half the mulch and leave the rest in place for the winter.

Keep the soil moist until the arrival of first frost, and then discontinue watering until the following spring.

In the spring, the seedlings will begin to grow again. After the danger of frost passes, carefully remove the old mulch.

Thin the seedlings as desired, keeping the strongest. You can thin them again when you decide which is the best of the bunch.

I don’t recommend saving acorns to plant next spring.

While some sources recommend storing them in damp vermiculite in a plastic bag in a cool, dry location, or in a plastic bag in the fridge, moisture can cause them to become moldy, or to germinate well before they are needed.

Transplant from Nursery Stock

Because growers typically tailor deliveries to local hardiness zones, you’ll get your sapling at the right time to plant it, after the first fall frost date and before the last frost date in spring.

Trees are dormant during this period and transplant shock is minimal.

Choose a location that can accommodate a mature width of 50 to 60 feet.

Take into consideration overhead power lines to avoid branch entanglement in the future. And if you know where your sewer line is, you’ll save yourself heartache down the road if you can keep the roots away from it.

If you have existing shrubbery and perennial plantings, think about the shade the tree will cast on them if it is planted in proximity.

Whether you have a young tree in a container or a more mature one with burlap-wrapped roots, you’ll need to start by working the soil to a depth and width twice as deep and wide as the container or root ball.

Crumble the clods of earth and remove debris, like grass, rocks, sticks, and weeds.

Settle the tree at a depth that is the same as in the container.

For a burlap-wrapped root ball, place the crown, where the trunk and roots meet, slightly above ground level to allow for some settlement after watering.

Backfill firmly so the trunk stands up straight.

Make a ridge of soil about six inches high about a foot away from the trunk.

Water deeply inside the ridge, like a moat.

Tamp the soil and add more as needed to restore level ground.

Use the moat to water for the first few weeks. Smooth it out before applying mulch, a topic we’ll cover shortly.

First, let’s find out how to care for a tree once growing is underway.

How to Grow

Full sun is essential – Q. muehlenbergii has zero tolerance for shade.

Choose your location wisely to avoid having to relocate and possibly damage the long taproot typical of an oak tree.

In its natural habitat, chinkapin oak grows on rocky limestone outcroppings. In the home landscape, it does best in organically-rich loam, although it tolerates soil of average quality.

The ideal soil pH ranges from slightly acidic to alkaline, or about 5.0 to 8.2. It must have excellent drainage.

Full sun, six hours per day minimum, is required for optimal development. When a tree is young, it may tolerate some shade but loses this tolerance as it ages.

Watering is an essential task, especially during the first year after planting. University of Minnesota Extension experts recommend the following care for young trees:

For the first two weeks, water daily.

For weeks three to 12, water every two to three days.

After that, water once a week as needed depending upon rainfall.

Per the extension pros, a tree needs more water as the trunk grows in diameter. So, for a three-inch trunk, you’ll need one to one and a half gallons per watering.

Once mature, a chinkapin has some drought tolerance. However, supplying enough water during a dry heatwave may pose a challenge.

In such a circumstance, you may find a soaker irrigation hose useful.

Another option is a slow-release tree watering bag.

Instead of watering a sapling daily, you can fill this 20-gallon Tree Soaker Watering Bag provides eight to 10 hours of slow-drip irrigation.

Made of UV-protected PVC, it’s rip-resistant with conveniently long lift straps, a heavy-duty zipper, and heat welded seams.

The Tree Soaker Watering Bag is available via Amazon.

Fertilizing is another consideration. You may want to conduct a soil test to determine what nutrients your soil may be lacking.

Fertilizers come in various forms – granular, liquid, and spikes. The best is a slow-release product that feeds gradually.

The University of Missouri Extension pros recommend not fertilizing at planting time to avoid encouraging leaf formation at the expense of root development.

Instead, they suggest waiting until a month after planting and then doing a light topical application of a nitrogen-rich product.

Take care to keep fertilizer at least a foot away from sapling trunks to avoid burning.

You may want to employ an arborist to plant and care for your tree. Depending upon the size you buy, you could be investing several hundred dollars.

If you choose to plant your own, ask the purveyors if there is a guarantee and replacement option in the event of a failure to thrive. They may even plant it for an additional fee.

Growing Tips

- Full sun is essential.

- The ideal soil is slightly acidic to alkaline, organically rich, and well-draining.

- Consistent moisture is necessary and watering must increase as the trunk grows wider.

- Fertilizer at planting time is not required and may be detrimental to root development.

- A large shade tree is an investment – consider hiring an arborist for planting and care.

Pruning and Maintenance

While you’ll read that chinkapin is a low-maintenance tree, I beg to differ.

Granted, it is pretty self-sufficient once established in the home landscape, barring pest or pathogen challenges.

However, with an enormous mature tree, there are piles of leaves to rake and loads of acorns to pick up in a heavy mast year.

However, if you invest in a chipper, like my dad did years ago, you’ll be in gardener heaven with leaf mulch galore.

Mulch is an excellent choice for weed control to minimize competition for water and inhibit pests and pathogens.

The pros at the Penn State Extension stress the importance of mulching.

Apply mulch in mid-spring to aid in weed control, moisture retention, and ground temperature regulation.

Place it in a ring around the trunk out to the drip line. Start the mulch 12 to 18 inches away from the trunk to avoid moisture buildup and rotting.

Choose an organic product, like compost, leaf mulch, or pine needles that break down to enrich the soil.

For heavier materials, apply two to four inches, and for lighter ones, one to two inches, to allow the roots to breathe.

Early each spring, rake away the old mulch.

Apply a slow-release fertilizer and water per package instructions.

Wait a day or two for the ground to dry, and add a fresh layer of mulch.

An arborist may fertilize mature trees with a different method, like an injection in the trunk, or a soil drench.

Continue to water regularly, taking rain into consideration. Remember, it takes about 30 years to reach full maturity, and even then, supplemental water is needed if it doesn’t rain.

Monitor for signs of insects or diseases, like discoloration, disfigurement, wilting, or premature leaf drop.

You may wish to consult an arborist to initiate a preventative regimen of treatments to minimize the risk of pest infestation and disease.

As your tree grows and becomes too tall to reach comfortably, you may need an arborist to climb it to remove damaged and/or dead branches.

Pruning for health and aesthetics is a winter task made easier in the absence of foliage.

Where to Buy

When a reputable nursery makes a tree available, it’s time to buy one. Rest assured it will be delivered to your growing zone at the appropriate time for planting.

The pros at Nature Hills Nursery recommend planting young oaks, as they withstand the stress of transplant better than older ones.

Chinkapin oaks are available from Nature Hills Nursery.

They also suggest an application of Root Booster at planting time.

It contains microscopic mycorrhizae fungi to promote healthy root growth.

Root Booster is available from Nature Hills in eight-ounce single-application packets.

Managing Pests and Disease

While it’s not uncommon for a chinkapin oak to live for over 100 years, there are pests and diseases you may need to address during its long and beautiful life.

Common pests include:

- Acorn Weevils, Curculio spp.

- Carpenter Worms, Prionoxystus robiniae

- Columbian Timber Beetles, Corthylus columbianus

- Gall-Forming Cynapids, Callirhytis spp.

- Spongy Moths, Lymantria dispar

- Little Carpenter Worms, P. macmurtrei

- Acorn Moth Larvae, Blastobasis glandulella

- Filbertworm Moth, Cydia latiferreana

- Oak Timber Worms, Arrhenodes minutus

- Orange-Striped Oak Worms, Anisota senatoria

- Two-Lined Chestnut Borers, Agrilus bilineatus

- Variable Oakleaf Caterpillars, Heterocampa manteo

- White Oak Borers, Goes tigrinus

In addition to pests, common diseases and the pathogens that cause them include:

- Anthracnose, Gnomonia veneta

- Canker, Strumella coryneoidea, Nectria galligena

- Oak Leaf Blister, Taphrina spp.

- Oak Wilt, Ceratocystis fagacearum

Often the best way to address these pests and diseases is with preemptive applications of products like fungicides and insecticides.

These proactive measures, combined with proper planting in full sun, adequate water, fertilizer, and mulching, go a long way toward keeping a tree pest and disease free.

Consult an arborist to discuss injecting trees preventatively to reduce the risk of infestation or infection.

Best Uses

Chinkapin oak is a large landscape tree that functions best as a stand-alone specimen.

Placement on the south side of a home is ideal for sun exposure and to cast shade where it is most appreciated.

Be sure the location has no physical impediments, like overhead wires that would require it to be pruned, spoiling its natural shape and dimensions.

Companion trees in the vicinity may include other oaks, maples, chestnuts, and beeches. Q. muehlenbergii tolerates juglone toxicity, so don’t hesitate to plant it near a black walnut that contains this toxic organic compound.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Deciduous tree | Foliage Color: | Green/green (yellow, orange, brown in fall) |

| Native to: | Central and eastern North America | Maintenance: | Medium |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 4-7 | Tolerance: | Average soil, black walnut juglone, some drought |

| Bloom Time: | Spring | Soil Type: | Organically-rich loam |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil pH: | 5.0-8.2 |

| Time to Maturity: | 30 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 50-60 feet | Companion Planting: | Beech, black walnut, chestnut, maple, oak |

| Planting Depth: | 3/4 to 1 inch deep (seeds); same depth as original container (transplants); roots with crown slightly above ground level (saplings in burlap) | Uses: | Landscape specimen, shade tree |

| Height: | 50-60 feet | Order: | Fagales |

| Spread: | 50-60 feet | Family: | Fagaceae |

| Growth Rate: | Slow to moderate | Genus: | Quercus |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Species: | Muehlenbergii |

| Common Pests: | Acorn weevils, carpenter worms, Columbian timber beetles, gall-forming cynapids, spongy moths, little carpenter worms, moth larvae, oak timber worms, orange-striped oak worms, scale, two-lined chestnut borers, variable oakleaf caterpillars | Common Diseases: | Anthracnose, canker, oak leaf blister, oak wilt |

A Living Legacy

At maturity, chinkapin oak commands attention as it soars into a sunny blue sky.

Isn’t it time to plant a tree in your landscape that can live for hundreds of years, casting shade on those below its expansive branches and sustaining wildlife?

With best planting and care practices – like a full sun location, well-draining soil, regular watering, appropriate fertilization, mulch, and proactive pest and disease measures – you can cultivate a living legacy to be enjoyed for generations to come.

Are you growing a chinkapin oak tree? What do you love most about it? Please share your thoughts in the comments section below.

If you enjoyed reading about this species and are looking for other large, long-lived landscape trees, we recommend reading the following next: