Pilea peperomioides

Chinese money plants are immediately recognizable by their fascinating round, flat foliage which attaches to the petioles in the middle of the leaves. Many gardeners frequently compare them to UFOs, pancakes, and coins.

They are sometimes likened to species like nasturtium (Tropaeolum spp.) and Peperomia, which have a similar leaf shape and attachment, though there are many notable differences between them.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Their easygoing nature and unique shape would be enough to recommend Chinese money plants, but these green wonders also have a charming origin story that makes me love them even more.

They’re known for bringing people together and fostering friendships.

We’ll talk about all that and more in this guide. Here’s the rundown:

What You’ll Learn

Like I said, pancake plants have a fascinating history that I find positively sweet. Let’s talk about that first.

What Are Chinese Money Plants?

Pilea peperomioides is part of the nettle family, Urticaceae, and closely related to stinging nettle (Urtica dioica). But don’t worry, it’s hairless and isn’t going to give you the same itchy, burning rash that other nettles can.

It’s also commonly referred to as lefse plant, UFO plant, mirror grass, missionary plant, and friendship plant. Note that there is another Pilea species (P. involucrata) known as friendship plant, and you can read about it in our guide.

Chinese money plant is indigenous to the Sichuan province and the west of Yunnan province in China.

In the wild, P. peperomioides grows above 4,500 feet in wet, rocky, forested areas. It stands out because the species has nearly round leaves with the stem (or petiole) connecting near the center, which is known as a peltate attachment.

While the origin of the name Chinese money plant isn’t clear, it’s a safe bet that it has to do with the coin-shaped leaves.

The peltate leaves emerge slightly cupped, but they flatten out as they mature. They might also take on a cupped shape if the plants are stressed.

As the upright stem matures, it turns brown, but young stems are green.

When mature, it can reach up to 18 inches tall and wide.

P. peperomioides is self-fertile, and in the spring or summer, thriving specimens will produce pink, white, or pinky-white blossoms on long stems. This even happens on those growing indoors.

Sadly, in its native habitat, P. peperomioides is endangered.

If you’re thinking of cultivating P. peperomioides outdoors, it can tolerate a brief freeze, though sub-zero temperatures will kill the aboveground parts. Provided it is only brief, the roots will survive and send up new growth.

It can be safely grown outdoors in Zones 10 and 11, and even in Zone 9 if you commit to adding a thick layer of mulch around the plant in the winter and covering it during an extended freeze.

Cultivation and History

Until the 1980s, P. peperomioides wasn’t well known outside of its native China, except in Scandinavia, where it is decidedly not native.

The first Westerner to identify the species was botanist George Forrest from Scotland on an expedition to the Yunnan province in 1904.

While he was there, he helped inoculate local people against smallpox and collected plant specimens and seeds to send back to the United Kingdom.

Then in 1945, Agnar Espergen, a Norwegian missionary, brought his own specimen home from the Yunnan province, and its popularity as a houseplant rapidly spread throughout Scandinavia.

Here’s the part of this story that I really love:

It became popular quickly because hobby growers realized just how easily P. peperomioides can be propagated from cuttings. They shared it far and wide in the region with friends and fellow plant-lovers, which is how it became known as the friendship or pass-along plant.

I love a plant that gained a following organically simply because people enjoyed sharing it with each other.

The Chinese money plant finally found its way to the rest of Europe and North America in the late 20th century.

It was identified by experts at Kew Gardens in 1978 after a hobbyist named Mrs. D. Walport sent a specimen to them looking for information.

They couldn’t identify the plant at first, but were able to figure it out after an assistant at the gardens named Sally Jellis brought the specimen to various experts who compared it with plants originally sent by Forrest to Edinburgh.

In 1993, the Sunday Telegraph in London asked readers for more information about the plant, and it was eventually determined by a reader that the specimen sent to Kew Gardens had arrived in the UK via Norway, where it was already widely grown. Whew!

Still, it didn’t really become hugely popular in the US and England until the early 2000s. These days, it’s no surprise to run into one at a store. It’s extremely popular.

Chinese Money Plant Propagation

Pilea species are super easy to propagate because they develop clones of themselves called pups or offsets.

In addition to separating these offsets, you can propagate via cuttings or purchase a potted plant from the store.

From Cuttings

You can propagate both stem and leaf cuttings from your P. peperomioides. It’s best to do this in the spring or summer, but you can do it anytime.

To take a leaf cutting, look for a large, healthy leaf and cut it off at the stem with a sharp knife or razor. Be sure to remove a little bit of the heel, which is a bit of the stem at the end of the petiole.

A stem cutting simply requires a section of stem that includes at least one node.

Stick the end of the leaf in or lay the stem section sideways on top of moistened potting medium in a pot.

Place the container in an area with bright, indirect light. Keep the medium moist and wait for roots to develop. You’ll know they have once new green growth emerges.

From Plantlets

Pilea grow pups from their roots and on the stem. Those that emerge from the roots are easiest to propagate since you can take a little root with the plantlet and pot it up.

You can do this any time of year, but spring is best.

Wait until the pups are at least a few inches tall with at least three leaves. Pups emerging from the main stem should have a little stem of their own. The larger the pups the better the chance they’ll survive.

To pot up a pup in the soil, gently tease the offset up and out of the soil as much as you can without damaging the parent. Then, dig down around the stem to locate the roots. Cut away the pup and some roots using a clean knife or pruners.

Place the pup in a small pot filled with standard potting soil. Water the soil and firm up the plant to make sure it stays put. Keep the soil moist and after a few weeks it should develop roots.

To take the plantlet off the stem, take a clean, sharp knife or razor and cut away the pup as close to the stem as possible.

Place the youngster in a glass of water and let it develop some roots. This takes a week or two. Change the water every few days to avoid mold.

Once roots have developed, pot it up in a small container filled with potting soil and water well.

You can also put the pup directly into potting soil, but I’ve had better luck with the water method.

Keep your pups in the same kind of light that you would keep the mature specimen.

Transplanting

If you bring home a purchased nursery start, at some point, you’ll want to move it from the grower’s pot and put it in a new one.

Choose a container one size up from the existing pot and place a thin layer of potting soil in the bottom.

Look for a rich potting mix that is water-retentive and well-draining with a pH that is slightly acidic to neutral.

Most houseplant mixes will fit the bill, but I always recommend FoxFarm’s Ocean Forest potting mix.

It has forest humus, bat guano, fish meal, earthworm castings, and moss in a combo that keeps all of my houseplants as happy as can be.

FoxFarm Ocean Forest Potting Mix

You can find one and a half cubic foot bags available via Amazon.

Carefully remove the plant from its pot and gently loosen up the roots a little. Place the plant in the new container at the same depth it was previously, and fill in around the roots with potting soil.

How to Grow Chinese Money Plant

Pancake plants prefer bright, indirect light. Within two feet of a window with sheer curtains, or just to the side of a window where it won’t be hit by direct light would work nicely.

Avoid any direct light. Too much light will cause heat stress and the leaves will start to curl back and develop wrinkles.

If the petioles become long and droopy, that is a sign it’s not exposed to enough light.

Variegated cultivars will lose their color if they’re exposed to too much or too little light.

Water when the top two-thirds of the potting medium has dried out. I’m assuming you are growing your Chinese money plant in a pot with drainage holes at the bottom (you are, right?). If so, you need to empty any cachepot or saucer about 30 minutes after watering.

Overwatering can cause the leaves to droop and curl into themselves.

Speaking of containers, P. peperomioides has a small, shallow root system. Remember, in their native habitat they grow in rocky areas so they don’t have the opportunity to develop deep roots.

If you use a deep pot, you run the risk that either the roots won’t be able to reach the moisture in the soil, or you will have to provide an excessive amount of water to bring the water up high enough for the roots to access.

A shallow pot or one that is no deeper than twice the width of the specimen is ideal.

Don’t use a deep pot and fill up the bottom with rocks or broken pottery. This is bad gardening advice and a myth that simply won’t die. Rocks in the bottom of a pot won’t improve the drainage and provide a place for water to drain so the roots won’t drown.

The change in texture from the potting medium to the rocks in the base causes the water to pool above the rocks via a method called capillary action.

Chinese money plants prefer humidity of around 50 to 75 percent. You can group a few houseplants together to raise the relative humidity or run a small humidifier.

Even better, keep your Chinese money plants in a bathroom or near your kitchen sink, which tend to be the most humid areas in the home. Pebble trays don’t do much to raise the humidity, so I don’t recommend them.

We might not realize it since we don’t get the chance to see the plants in their native environment, but many of the species we grow as houseplants remain in a perpetually juvenile state.

They’re more attractive that way, since mature specimens can be bulky and leggy, and they stay a more manageable size. Pothos, philodendron, monstera, and pilea are all kept juvenile, for the most part.

As your Chinese money plant grows, it tends to start dropping the lower leaves and can end up looking leggy and bare. Every few years, unless you like the leggy look, you might want to cut off the bushy top of the stem and propagate it as described above.

A few leaves dropping here and there is totally normal. The lower leaves drop off as they age.

But if your specimen starts acting like a deciduous tree and lots of leaves start turning yellow and dropping, especially in the fall, it means that it was exposed to too low temperatures too rapidly.

You’ll often see this with plants placed close to a window, because it can be significantly colder near a window than many of us realize.

Chinese money plants must be kept in temperatures between 60 and 80°F. Anything below 55°F and you run the risk of harming it. Keep it away from exterior doors, single-pane windows, or air vents.

If you want to encourage a symmetrical shape, rotate the pot a quarter turn every month.

Feed your specimen every week with a mild, balanced fertilizer. There are many good houseplant-specific fertilizers available.

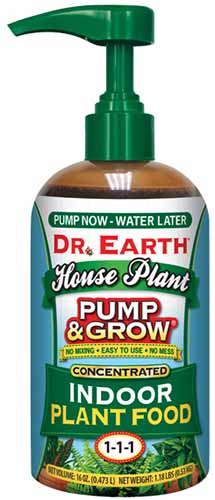

Dr. Earth’s Pump and Grow, for instance, has an NPK ratio of 1-1-1 and is made using waste scraps from grocery stores.

Grab a handy 16-ounce pump bottle at Arbico Organics.

Growing Tips

- Provide bright, indirect light.

- Water when the top two-thirds of the pot has dried out.

- Maintain temperatures between 60 and 80°F.

Pruning and Maintenance

As the leaves age, they turn yellow. You can snip or pull these off. Be aware that leaves can also turn yellow if you are overwatering.

You can tell the difference because in the case of overwatering, the leaves will be soft as well as yellow, and it won’t just be the older leaves that will change colors.

Leaves might also turn yellow if they’re exposed to too much light. In this case, they will retain their typical texture but they’ll turn a pale, light yellow.

Wipe the leaves every few weeks with a damp cloth to remove dust. If too much dust builds up on the leaves, the plant will suffocate and can’t photosynthesize.

This also removes the water marks that inevitably build up when water splashes or accumulates on the leaves.

As they mature, the lower leaves drop and the plant will take on a tree-like shape. If you don’t like this, you’ll need to snip the trunk off about halfway down right above a leaf node.

It will send out new, bushy growth at the spot where you cut it. Otherwise, just let it take on that natural shape.

Chinese Money Plant Cultivars to Select

The vast majority of specimens you’ll find for sale are species plants, but there are a few variegated cultivars available.

Variegated cultivars aren’t as common, but they’re worth searching out because they’re beautiful.

But so is the species, and if you prefer one of those, you can buy a live specimen in a six-inch pot at Fast Growing Trees.

Mojito

Break out the drinks, we’re going to celebrate with ‘Mojito.’

This cultivar is like the species in every way except for one special difference: the leaves are speckled in hues of dark and lime green, like chunks of muddled basil floating around in your cocktail.

Sugar

‘Sugar’ is a sweet little cultivar that looks like it has been dusted in sugar granules, with lots of white speckles covering the foliage.

White Splash

The leaves of ‘White Splash’ are freckled in tiny dots of white, like someone splashed the foliage with white paint.

Plus, the variegation is stable and new leaves and pups will consistently show the coloration.

You can nab a starter plant in a two-inch pot from Optiflora via Amazon.

Managing Pests and Disease

Keep your plant healthy, and it’s unlikely that pests or pathogens will come calling. If you are unlucky enough to encounter a problem, here are the ones you will most likely see:

Insects

If you examine your plant to look for pests and you notice salt-like deposits on the underside of the leaves, it’s nothing to worry about.

These aren’t insect eggs, the discoloration is caused by mineral deposits that form on the foliage as it ages.

Aphids

Aphids are small, pear-shaped insects that use their sucking mouthparts to draw the sap out of the plant. The result is drooping, yellowing, and stunted growth.

Most of us will encounter aphids at some point in our lives, so don’t panic if you notice these pests clustering on the stems and undersides of the leaves.

Also watch for the sticky honeydew that they leave behind and the black sooty mold that it attracts.

First, isolate your Chinese money plant. Then, read our guide to learn about dealing with aphids. My preferred method is to spray them off with water, but you can also use insecticides.

Mealybugs

Mealybugs are small insects from the family Pseudococcidae that feed on plants. They’re closely related to scale insects, but instead of armor, they have a waxy coating that protects them.

Not only do they feed on the sap but they can spread disease as well.

When they feed on Pilea, it causes the leaves to turn yellow and may even result in stunted growth.

Examine any specimen that looks unhealthy to see if there are any signs of these bugs, which tend to cluster in groups on the stems and undersides of the leaves.

If you see them, check out our guide to mealybugs to learn all about dealing with these pests.

It’s easier than you might think. You can wipe them with a cotton swab dipped in isopropyl alcohol, which removes their protective coating and leaves them open to the elements.

Scale

Closely related to mealybugs, scale are flat, oval insects that look like little lumps on the leaves and stems.

They’re less common on houseplants than scale and aphids, but you still might see them. If you don’t see the insects themselves, look for leaf yellowing and drooping.

If you see scale, or the honeydew they leave behind, check out our guide to learn how to deal with them. You can use the same methods for removing mealybugs to remove scale.

Disease

It’s unlikely that you’ll have disease issues with your Chinese money plants. They’re tough and rarely bothered. Overwatering, however, can result in root rot.

Root Rot

Root rot is caused both by overwatering and pathogens in the Pythium genus.

Pythium species are oomycetes, or water molds, that cause roots to turn black and mushy as they die.

Even when the pathogens aren’t present, overwatering can drown the roots and deprive them of oxygen.

Either way, if the leaves are drooping and turning soft and brown, unpot the plant, remove the soil, and inspect the roots. Are they black and mushy? If so, use a clean pair of scissors and cut off all the dead material.

Next wipe out the container with a 10 percent bleach solution (one part bleach to nine parts water) and dispose of all the old soil.

Spray the roots with copper fungicide and repot it in fresh potting soil – and make sure to water much less than you were previously.

Once a month, drench the soil in copper fungicide.

If you don’t already have copper fungicide in your gardening arsenal, it’s handy to have around because it’s useful for treating so many different diseases.

Pick some up at Arbico Organics in 32-ounce ready-to-use or 16-ounce concentrate.

We have a comprehensive guide on managing root rot here.

Best Uses for Chinese Money Plants

The long stalk of P. peperomioides can be shaped, braided with others, or left to grow upright to look like a tree.

I’ve seen trailing Chinese money trees, those with five braided stems, and those kept short and bushy. You could grow one as a tree with pothos trailing out of the pot.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Tropical perennial | Flower/Foliage Color: | Pink, pinky white, white/green, yellow, white |

| Native to: | China | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 9-11 | Tolerance: | Low light |

| Bloom Season: | Spring, summer | Soil Type: | Loose, airy, humus-rich |

| Exposure: | Bright, indirect light | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.5 |

| Time to Maturity: | 2 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Height: | 18 inches | Uses: | Trailing, tree habit, bushy houseplant |

| Spread: | 18 inches | Order: | Rosales |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate | Family: | Urticaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Pilea |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, mealybugs, scale; Root rot | Species: | Peperomioides |

Pass it On

This popular houseplant is tough, unfussy, and eye-catching. It’s a blast to have around, which is all the more reason that it’s your turn to pass the friendship plant along.

I sincerely hope you learned all you hoped about growing (and sharing) Chinese money plants. How are you going to grow yours? Do you plan on keeping it bushy and short? Tall like a tiny tree? Share with us in the comments section below!

Now that you’ve mastered growing Chinese money plants, maybe you want to try other houseplants with similar growing requirements. If so, here are a few guides you might be interested in: