If you’ve ever smelled something oniony in your yard and seen hollow-stemmed, grasslike herbs growing there, you might be dealing with wild chives (Allium schoenoprasum).

But what are wild chives, exactly? Will they spread everywhere? Can you eat them? What do you do with them?

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

In this guide, we’ll answer all of these questions.

Here’s what we’ll dig into:

All About Wild Chives

What Are Wild Chives?

These succulent, hardy members of the Allium genus grow along rocky creek banks and lakes, as well as in marshy meadows and grassy yards, from Zone 3 in Alaska down into the lower 48 states, as far south as Zone 8 and sometimes Zone 9.

They begin growing in early spring before the rest of the natural world has fully awakened to the new season.

To spot them, look out for telltale bunches of grasslike green leaves rising above old, dead grass. You’ll know the clumps aren’t grass when you get closer and see the cylindrical shape of the leaves, which grow 12 to 24 inches tall and can spread up to 12 inches.

You might not be looking at wild chives, though. Onion grass (A. vineale) looks almost identical to A. schoenoprasum and often pops up in lawns. Other alliums that closely resemble wild chives can also appear in your yard, including wild garlic (A. canadense), and onion weed or three-cornered leek (A. triquetrum).

The bad news is that in the United States, A. canadense, A. triquetrum, and A. vineale are seen as weeds. Onion grass is even listed as an invasive weed that can affect the taste of nearby crops of wheat or other grains, though it is a native plant in parts of Europe.

If you don’t live near wheat fields and don’t mind a weedy lawn, the good news is that onion grass, wild garlic, onion weed, and most other alliums are edible and make tangy additions to salads, soups, and more.

Not sure what you’ve found in your yard, but it smells like onion? Take it to your local extension office and see if they can help you identify it. And if it doesn’t smell oniony, don’t eat it!

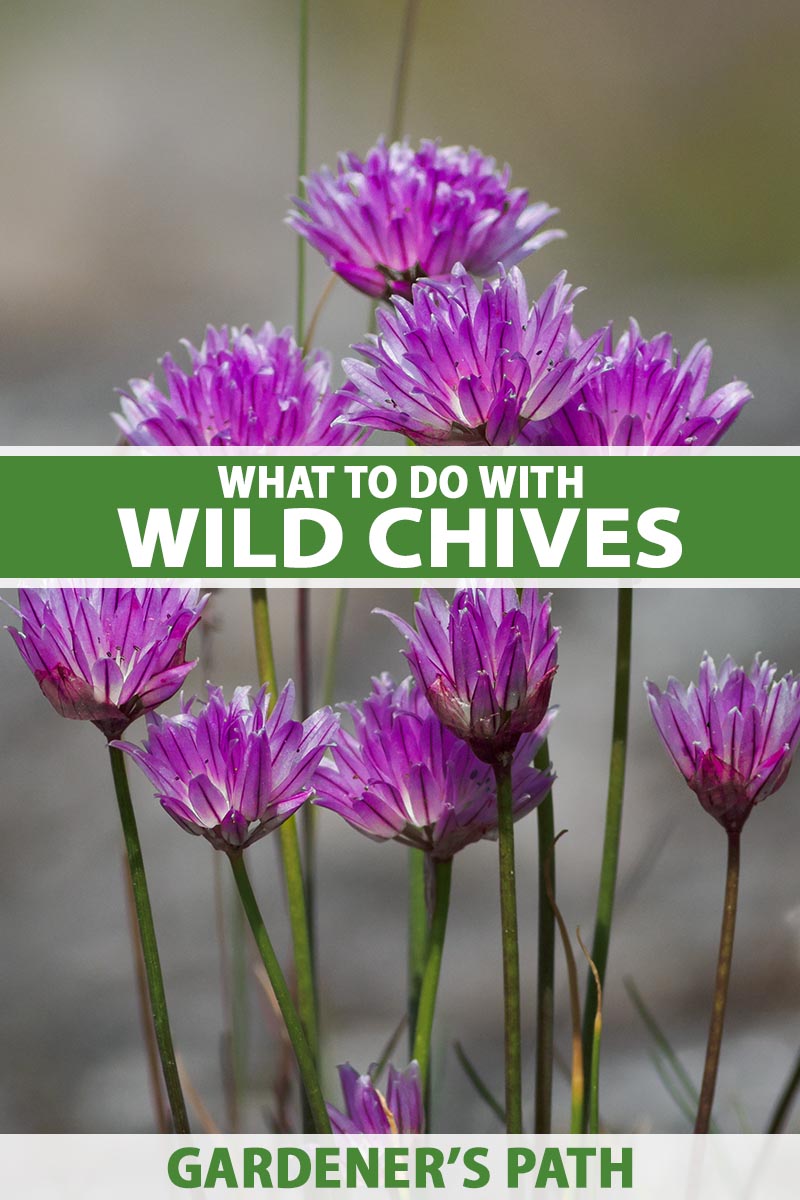

By May or June, if it isn’t cut down first, A. schoenoprasum produces clusters of pinkish-lavender flowers atop straight flower stalks.

Native to Eurasia, wild chives were naturalized in North America long ago, and have been an important part of indigenous peoples’ diets in the Western Hemisphere for many years.

The leaves have long made a perfect flavoring for savory meats and vegetables. Indigenous communities have also used the plants in traditional medicine, to help treat coughs, colds, and minor wounds.

It’s easy for the cultivated garden variety to escape the confines of your garden and grow in your yard, so it’s possible that the clumps that are suddenly growing among your grass aren’t truly wild A. schoenoprasum at all.

To make things even more exciting, it can be virtually impossible to tell the true wild species apart from garden escapees!

There are some key differences, though: in the wild, A. schoenoprasum tends to grow taller with thinner stalks and smaller flowerheads than its cultivated counterparts.

As far as flavor, use, and edibility are concerned, there’s no meaningful difference between cultivated plants, escapees from gardens, and true wild chives growing in their native or naturalized habitats.

Here’s how to identify any chive that’s growing beyond the bounds of your garden:

Identification Tips

It’s crucial to know that what you’re looking at and potentially eating is wild A. schoenoprasum and not something potentially deadly, like the similar-looking mountain death camas (Anticlea elegans).

This lookalike can make humans and animals extremely sick if ingested and can even cause death.

In both of these plants’ early stages, the grasslike blades look similar.

But unlike wild chives, mountain death camas have flat blades and cream-yellow flowers.

Most notably, the deadly plant doesn’t smell like an onion when you crush a leaf between your fingers.

This is a key component to correctly identifying a chive in nature. Does it have hollow, cylindrical leaves that smell like an onion when crushed?

Then it is most likely a wild chive.

Or, it could be one of the Alliums we mentioned before. Here’s a quick look at key differences between these Alliums and our star, wild chives:

Onion Grass (A. vineale)

A. vineale is hardy in Zones 4 through 8. Also called “crow garlic,” this one looks so much like chives it’s uncanny.

A key difference is that they can potentially grow a bit taller than chives – up to three feet – and they have a tougher texture than chives when eaten.

In addition, the purple, blue, or pinkish inflorescence in onion grass grows additional green scapes from the top, for a wild Albert Einstein hair type of look, except with green hair instead of white.

Onion Weed (A. triquetrum)

Also known as the “three-cornered leek” due to the grassblade shape of its flower stalks, this allium is only hardy in Zones 7 through 10.

Unlike chives, its flower stalks are not hollow. Plus, they bloom in small clusters of dainty, white, pendulous flowers.

Wild Garlic (A. canadense)

Also known as “meadow garlic,” wild garlic has chive-like hollow stems and dainty, onion-weed-like flowers, only they face up instead of down.

Unlike wild chives, it only grows up to one and a half feet tall. Wild garlic is hardy in Zones 4 to 8.

If you have any doubts at all about what you’re seeing in your yard, do not eat the plant. Take it to your local extension office or an edible plants specialist to make sure it is, indeed, A. schoenoprasum or a related edible weed.

And if it is, rejoice that you’ve found it in your yard or in the wild somewhere!

The plants will spread by reseeding or via their underground bulbs if you let them.

If you don’t want this to happen, pinch off the flowers before they bloom to help keep the wind from blowing seeds all over your yard. To get the bulb spread under control, you have to dig up the entire plant.

It’s important to dig and not pull, because tugging on the plant usually just causes the leaves to break away from the underground bulbs, making them harder to unearth.

Harvesting and Preserving

It’s easy to harvest these flavorful members of the onion family, but there’s a big caveat: in some parts of the United States, including Michigan, Minnesota, and New Hampshire, wild chives are a threatened or even endangered species.

Refrain from foraging in those states, and in any other areas where you may find out that the plant is a threatened or endangered species. (Do your research!) Instead, plant some cultivated chives in your garden.

Another thing to consider is that you don’t want to forage in areas that are polluted or potentially sprayed with harmful chemicals. Stay away from unfamiliar areas, roadways, chemical treated lawns, and the like.

In some states, like Maine, wild A. schoenoprasum grows freely along waterways: think creeks, streams, rivers, and lakes. These are probably the safest places to forage for wild chives.

To harvest, get a pair of scissors or a sharp knife, grasp a cluster of leaves with your fist, and slice them off about an inch from the ground.

Do this with the entire cluster, even if there are buds or flowers on the plant, because those are edible too, and they taste delicious in salads.

Within a day or two, you’ll see new shoots growing up from inside the cut leaves. In another two weeks, you can harvest the entire bunch of chives again.

Usually, you’ll be able to do this three or four times with one plant throughout a single growing season, the same as you might with chives cultivated in the garden.

If you have more of these delectable greens than you know what to do with, why not flash-freeze them for later use?

Chop them to whatever length you prefer, spread them on a baking sheet, and pop them in the freezer for two hours. Then, transfer them to a storage container and put them back in the freezer.

Use your frozen herbs within four to six months for the best flavor.

Recipes to Try

I love sprinkling wild chives on soups, salads, and avocado toast. When I find them in my yard during the summer up here in Alaska, I head out most mornings to harvest a few here and there for my morning omelets.

They’re also absolutely scrumptious in this recipe for easy sourdough biscuits with cheese and chives from our sister site, Foodal.

Top a bowlful of Foodal’s Buffalo chicken soup with wild chives to go along with your biscuits and you’ve got a perfect meal.

If you want something a little fancier but supremely comforting, use your foraged chives in this recipe for Western Tex-Mex crab cakes with lemon aioli, also from Foodal.

Jiving with Chives

No matter where you find them, stumbling upon a wild cluster of A. schoenoprasum is a delight.

Just make sure if you’re in a national park or other protected area – or on someone else’s property – that you ask before picking, and refrain from harvesting in places where these plants are known to be scarce.

Have you ever found these beauties in nature? Let us know in the comments section below!

And in the meantime, check out these articles on growing alliums in your garden next:

Thanks for the article! it’s was very helpful. I see chives all over my neighborhood and have always wondered if they were edible. I just transplanted one bunch from my backyard to a container.

I have lots of wild chives growing in my back yard along the creek bank. I wasn’t sure if that’s what they were until I picked one and it smelled like an onion. In the spring and summer we can smell them when we sit outside.