Daucus carota

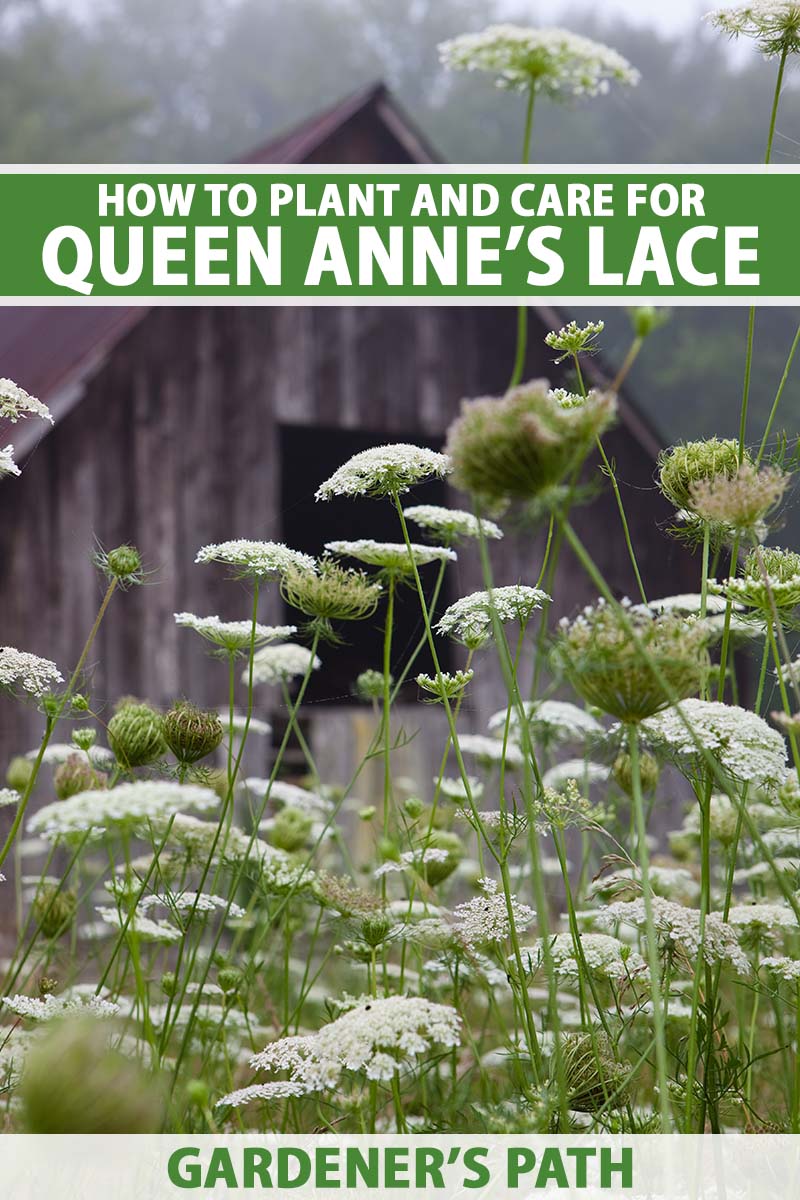

Sporting delicate white frills perched on tall stems, and that cute purple center flower that’s so often a feature, Queen Anne’s lace was one of my favorite childhood wildflowers. They grew everywhere.

One summer, my sister and I ambitiously harvested a few pails full, bundled and stuffed them into plastic sleeves, and sent them on the truck with my dad’s greenhouse-grown cut flowers to the flower auction.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

As common in ditches and on field margins as they were, they didn’t sell. But we couldn’t imagine why they hadn’t even made a few cents. They were so pretty!

I still love them, and their loose, textured boho look is back in style. Even better: they are magnets for beneficial insects.

If you decide to grow these easy, lacey blooms, whether as an extra wildflower or to add to bouquets, everything you’ll need to know is in this guide.

Here’s what I’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

Cultivation and History

Daucus carota, a member of the Apiaceae family, is native to Europe, Asia, and North Africa. It was introduced to North America from Europe, likely hitching a ride with 17th-century colonists in some cattle feed, straw, or hay.

It has naturalized in North America, Japan, New Zealand, and Australia, and is so successful it is considered a noxious weed in some states, including Iowa, Washington, Michigan, and Ohio.

Contact your local university extension office to find out if it is invasive in your area before you plant and to get a list of noxious weeds in your state.

Though it is well known as Queen Anne’s lace in North America, some call it wild carrot or bird’s nest.

The name Queen Anne’s lace is popularly thought to originate from its resemblance to the lace headdress of Anne of Denmark, queen consort of King James I of Scotland, England, and Ireland in the early 1600s.

Legend has it that she challenged her ladies-in-waiting to a contest to see who could make a piece of lace as beautiful as a flower, but none could beat hers.

Often, you’ll find a singular dark purple flower in the center of the umbel (flat flower cluster), and this is said by some to symbolize a drop of blood from when she pricked herself with a needle while sewing.

Over the course of the past 150 years, botanists have come up with a variety of reasons why the singular purple flower exists. Some say it mimics an insect visiting the flower, and this raises theories that it either dissuades passing insects from landing, or attracts predatory wasps.

The name wild carrot has a more concrete origin. D. carota are the tough-rooted and less tasty ancestors of the fleshy orange root vegetable we love to eat, aka D. carota subsp. sativus.

As the seed ripens, the drying umbel curls into a bird’s nest shape. Thus, the common name bird’s nest!

The entire D. carota plant is edible, though not as tasty as the domesticated subspecies grown for edible use.

The taproots are best in their first year, and can be cooked as a vegetable, or dried, roasted, and ground as a coffee substitute.

You can try steeping the flower heads for teas or battering and frying for a special treat. The leaves smell and taste like carrots and can be added to soups and stews.

Be aware, though, that this plant can be a skin irritant for some, can cause phytophotodermatitis, and may stimulate uterine contractions. Proceed with caution.

Queen Anne’s lace has a few lookalikes, and some are very poisonous.

Bishop’s weed, Ammi majus, is a harmless doppelganger from the same botanical family and is sometimes sold by seed companies as a less invasive alternative under the name Queen Anne’s lace.

Lookalikes poison hemlock (Conium maculatum), water hemlock (Cicuta spp.), and fool’s parsley (Aethusa cynapium) are all poisonous. Make sure you know what you are looking at before touching and especially before eating.

Poison hemlock has a spotted stem, while Queen Anne’s lace is green, and water hemlock grows in wet areas, while wild carrot prefers dry locations.

A good way to differentiate between wild carrot and its poisonous lookalikes is to have a good sniff. Queen Anne’s lace leaves smell strongly of carrot.

Propagation

You can find blooming Queen Anne’s lace from spring to early fall. Two to five inches in diameter, each umbel contains up to 1000 flowers.

This plant propagates itself solely by seed, and self seeds very easily. The seeds are bristled and will latch onto fur and feathers to be distributed far and wide.

It doesn’t transplant well because of its long taproot, so direct seeding is the best way to propagate wild carrot.

Purchase seeds, or sow collected seeds directly into the ground as soon as they are ripe.

Alternatively, you may save collected seeds and sow them early in the spring. You can read a more detailed guide on how to harvest and store carrot seeds here.

Broadcast the seeds as you would other types of wildflower seeds, over soil that is loosened and moist.

When sown in the early spring, some may bloom the same season. However, most will concentrate their efforts on producing leaves and roots the first year, and won’t flower until their second season.

How to Grow Queen Anne’s Lace

Hardy in Zones 3 to 9, Queen Anne’s lace is a tolerant, easy biennial to grow. It thrives in low humidity and moderate temperatures.

Plant in full sun for loads of lovely, large white flower clusters. Partial shade is okay, but full shade will greatly decrease vigor.

Wild carrot prefers loamy, nutrient deficient soils, and dry conditions. It tolerates a wide variety of soil types, including chalk, clay, and sand. A slightly acidic to neutral pH of 5.5 to 7.0 is ideal, but this species may adapt to a wider range.

Once established, it doesn’t need to be watered. Deadhead if you want to prevent plants from self seeding and spreading.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full sun for optimum blooming and vigor.

- Dry soil is preferred.

- No need to fertilize.

Where to Buy

Many seed companies sell Ammi majus seeds under the common name Queen Anne’s lace. While plants look almost identical, these are not the true species, D. carota.

You can find species plants with the characteristic white flowers available from Seedsandscents via Amazon.

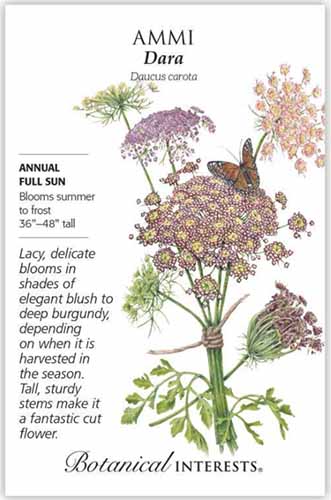

Dara

Daucus ‘Dara’ is an interesting cultivar, often listed as “flowering carrot,” chocolate lace flower, ‘Ammi Dara,’ or ‘Purple Kisses.

A standout in cut flower arrangements, It features pink and purple flowers instead of the white ones you see growing wild.

You can find ‘Dara’ seeds available from Botanical Interests.

Managing Pests and Disease

These wildflowers are generally low maintenance, but they can occasionally be bothered by a short list of insects and diseases.

They are hosts for domesticated carrot pests, so if you are growing carrots in your vegetable garden, consider planting the two as far away from each other as possible. Keep an eye on the Queen Anne’s lace to indicate possible carrot issues.

The seeds feed ring necked pheasants, ruffed grouse, and pine mice in the late fall and winter. Deer and rabbits snack on the foliage, but are not usually enough of a problem to worry about. Read about how to keep deer out of your garden here.

Insects

While it attracts some welcome visitors, including natural pest enemies and pollinators, some of the insects that will drop by your D. carota aren’t as beneficial.

Aphids

Several species, such as the carrot-willow aphid (Cavariella aegopodii), hawthorn-parsley aphid (Dysaphis apiifolia), and two species of honeysuckle aphids (Hyadaphis foeniculi and H. passerinii), will feed on wild carrot during the summer.

Leaf curling, reduced vigor and black mold growing on the honeydew exudates are some symptoms of aphid feeding.

The carrot-willow aphid also transmits carrot mottle virus and carrot red-leaf virus, which I’ll discuss below.

If you wish to treat for aphids, try applying an insecticidal oil such as Monterey Horticultural Oil, which is available at Arbico Organics.

Caterpillars

Wild carrot is an excellent food for the larvae of the black swallowtail butterfly (Papilio polyxenes) and the zebra caterpillar moth (Melanchra picta).

The swallowtail butterfly is a striking black winged beauty with colorful yellow and iridescent blue markings, distinct red-orange eyes, and the characteristic tails on its wings.

Many gardeners try to attract these stunning visitors, but if numerous enough, the larvae (aka caterpillars) can chew down an entire plant, no problem.

The larvae of P. polyxenes start out black with a white saddle and covered in spines. The spines then turn red-orange, and eventually the entire body becomes smooth and green with black transverse stripes dappled with yellow.

M. picta caterpillars are bright and easily recognizable, with black and white markings and yellow stripes. While they may infest a variety of agricultural crops, they also have a lot of natural enemies just waiting to attack as they develop.

The larvae of both of these caterpillars aren’t usually numerous enough to justify using insecticides, but gardeners can handpick the larvae if they are causing damage.

You can also apply a bacterial insecticide product which contains Bacillus thurengiensis v. kurstaki that will not harm beneficial insects.

Bonide Thuricide is available at Arbico Organics.

Disease

Diseases are rarely a problem for Queen Anne’s lace, but keep an eye out for the following two.

Carrot Leaf Blight

A significant agricultural disease, carrot leaf blight is caused by Alternaria dauci, a fungal pathogen that loves hot, wet weather.

The leaves and petioles develop angular spots, which widen and cause eventual leaf necrosis (aka death). This reduces yield in domestic carrots but is usually just an eyesore in ornamental Queen Anne’s lace.

You can apply a biological fungicide product such as CEASE, available at Arbico Organics, to try to control carrot leaf blight if it is ruining your wildflower garden.

This product contains Bacillus subtilis, and is safe for bees and the beneficial insects visiting the flowers.

Carrot Motley Dwarf

Carrot motley dwarf disease is a combination of two viruses, the carrot mottle virus and the carrot redleaf virus, which are vectored together by the carrot-willow aphid.

The symptoms look like a nutrient deficiency – the plant’s growth may be stunted, and the leaves turn yellow or red.

Besides controlling the vector aphid, removing all carrot and wild carrot residue from the garden before the winter is another good way to reduce the risk of infection.

Best Uses for Queen Anne’s Lace

Beautiful on its own in a vase or as a bouquet filler, in a bed by itself or mixed in with other wildflowers, Queen Anne’s lace is a versatile plant.

It makes a great companion plant as the pollen and nectar attracts a variety of beneficial insects, such as ladybugs and other beetles, flies and hoverflies, small bees, and wasps.

Plant near fruits or vegetables that need pollination or to attract predatory insects to help with pest control.

You can use it to fill bare spots in your garden with its feathery leaves and lacey flowers. Flowers may also be pressed and dried.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Flowering biennial/wildflower | Flower / Foliage Color: | White/green |

| Native to: | Asia, Europe, north Africa | Tolerance: | Varying soil types and pH, drought |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 3-9 | Maintenance: | Low |

| Bloom Time / Season: | Spring-early fall | Soil Type: | Chalk, clay, loam, sand |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil pH: | 5.5-7.0 |

| Spacing: | 12 inches | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | Surface sow | Attracts: | Butterflies, pollinators, and other beneficial insects |

| Height: | 36 inches | Uses: | Cut flowers, dried flowers, wildflower beds |

| Spread: | 20 inches | Order: | Apiales |

| Time to Maturity: | 2 years | Family: | Apiaceae |

| Water Needs: | Low | Genus: | Daucus |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, caterpillars; carrot leaf blight, carrot motley dwarf | Species: | Carota |

Lace Is Back

The wild, textured look is again popular in floristry and garden design, and adding Queen Anne’s lace is the perfect way to dive into this trend.

Whether you use it in bouquets or to add an extra pop of white frills in your landscape, the delicate leaves and feathery flowers add some neutral color, boho vibes, and best of all, attract beneficial insects.

I’d love to see a photo of your favorite flower bouquet featuring wild carrot, and while you’re at it, tell me about all the different insect good guys you discover in your wildflower garden in the comments section below!

And to learn more about how to grow and care for other umbellifers in your garden, you may enjoy these guides next: