Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

Referred to as timber rot, white mold, or sclerotinia stem rot, this disease can wreak havoc on tomato plants in cold, wet climates, and may persist in the soil for up to 10 years.

And it’s not only your tomatoes that may be at risk. White mold can infect more than 400 species of plants, including such important crops as potatoes and peppers.

Caused by the fungal pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, this disease is widespread in sub-tropical and temperate areas. Over 60 names have been used to date to refer to diseases caused by this pathogen.

Not surprisingly, it can also infect a large number of weeds, which can serve to maintain a reservoir of the pathogen.

Weed hosts include lamb’s-quarter, pigweed, Canada thistle, wild mustard, hairy nightshade, and ragweed – a who’s who of prominent weeds.

Here’s what I will cover:

What You’ll Learn

Sclerotinia Stem Rot Symptoms

A classic symptom of this disease is the production of structures called sclerotia that give the organism its scientific name. These survival structures look like rat droppings – small, black, hard, cylindrical objects.

The sclerotia form in or on dead plant tissue. You can find them inside tomato tissue that has turned white and dry due to the disease. This symptom in tomatoes gives the disease its alternate name, timber rot.

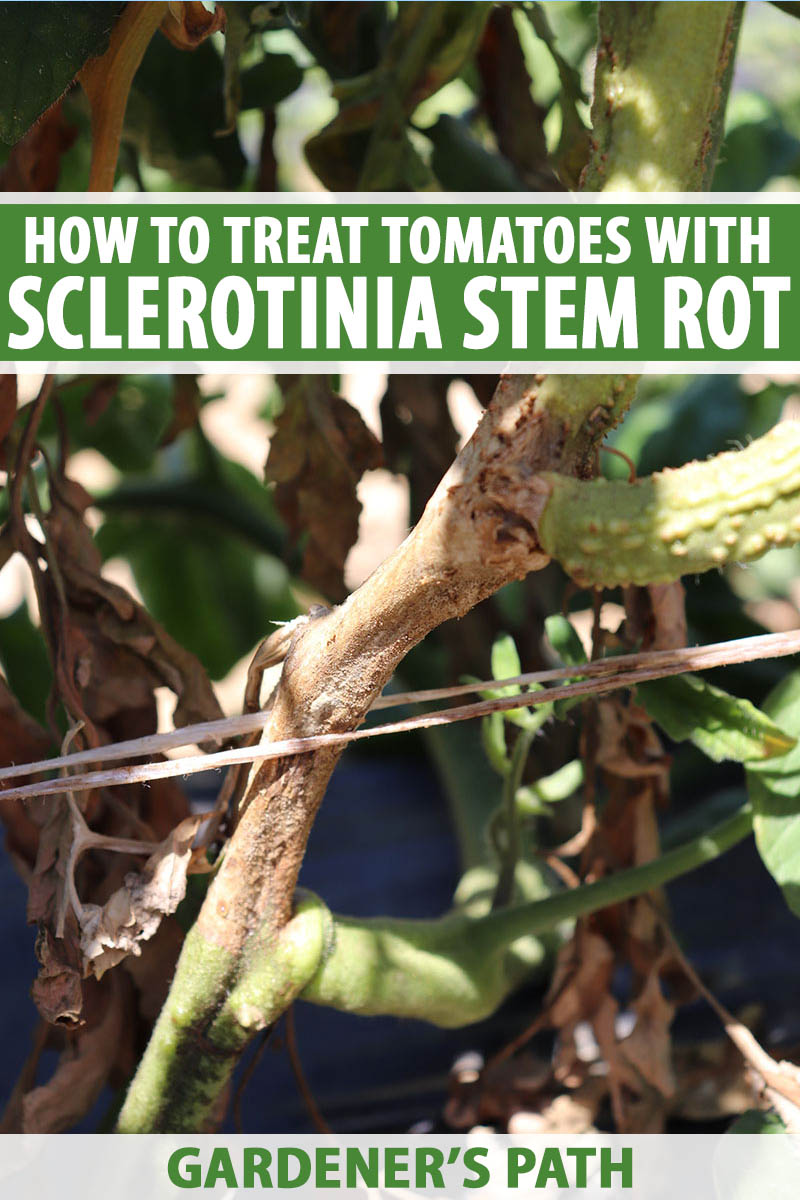

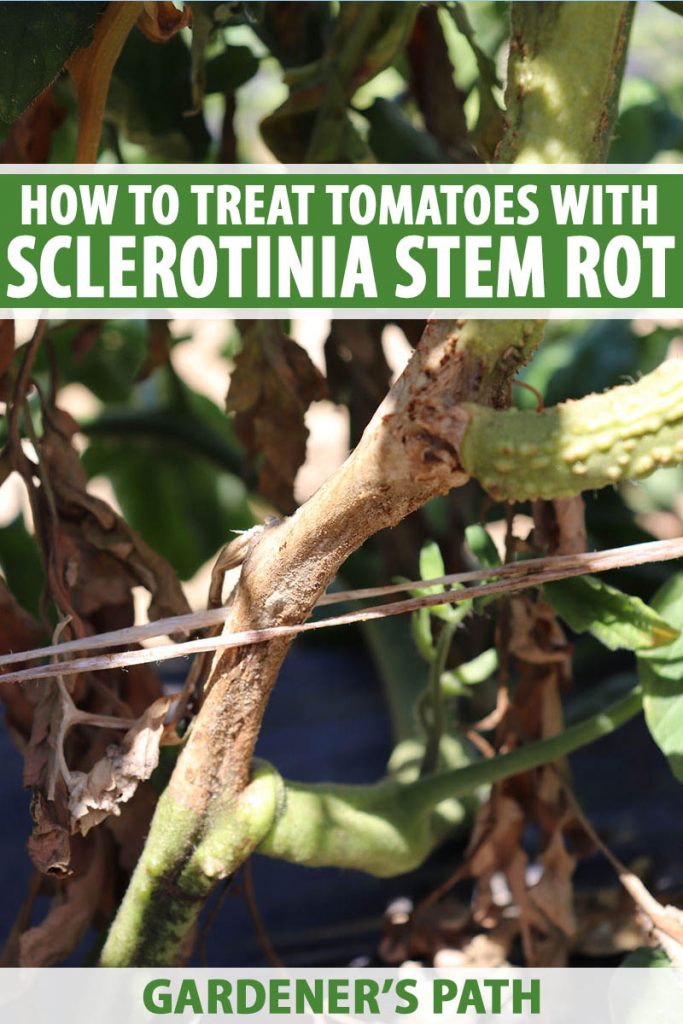

The first sign of infection by this pathogen is at the base of the main stem at the soil line or on lower branches. At first, the disease manifests as watery soft rots and bleached areas on the leaf axils and stems.

Next, a white fuzzy mold grows both inside and outside the plant. It then spreads to the flowers, petioles, leaves, and stems. The fruit can also be infected, turn gray, and rot.

As the disease progresses, the plant will wilt. The tissues become even more bleached and brittle, and in seven to 10 days, the black sclerotia are formed. If you cut the sclerotia open, their insides are pinkish-white.

Favorable Weather for Infection

White mold is a disease of cool, wet weather – temperatures from 59 to 70°F. Nighttime temperatures around 60°F are particularly favorable for infection.

Spores are most likely to infect tomato plants after 16-72 hours of continuous wetness with a relative humidity that is greater than 90 percent.

The plants are most susceptible when they are blooming, so pay particular attention to the flowers if the weather is cool and wet.

The Disease Cycle

If the environment is warm and dry, the sclerotia can stay in the soil for years – as infectious as ever.

Once conditions are cool and favorable for the fungus, the sclerotia within the top inch or two of soil germinate and produce fruiting bodies. You may be able to see these – they look like little mushrooms on the surface of the soil.

The fruiting bodies produce spores right above the soil line that are very sticky. These can survive on a leaf for up to two weeks under favorable conditions.

The spores typically germinate on susceptible tissue such as dead flowers. This is often the case in leaf axils where a flower blossom has fallen and become stuck.

Once the pathogen has become established in decaying tissue, it moves on to attack the healthy parts of plants.

The only good thing about this disease is that once it has completed its disease cycle, it will not produce spores until the next year when favorable conditions return.

However, you are stuck with those sclerotia in the soil – a harbinger of doom for your tomato plants.

How Your Garden Can Become Infested with Timber Rot

The most common way that timber rot is spread is by spores that blow through the air from infected crops or weeds, and land on your unfortunate plants.

If successful, the fungus will then produce sclerotia, which can spread the disease further in your garden.

The wind can also blow soil or crop debris infested with sclerotia into your garden.

Water can spread spores or sclerotia, and irrigation water is a common source of infection in commercial fields.

How to Manage Sclerotinia of Tomato

There are some techniques you can use to minimize infection of your plants.

Unfortunately, no resistant varieties of tomatoes are available currently, though genetic testing of resistance to this pathogen is underway.

When conditions are favorable, it is a good idea to inspect your plants periodically and remove and destroy any that show symptoms of this disease.

Given the wide host range of this pathogen, it is particularly important to double down on removing any weeds found in or near your garden.

Cultural Controls

What’s the most important factor in terms of cultural control in this case? Location, location, location, as they say.

Rotate your crops and avoid planting in soil known to be contaminated with this pathogen for at least five years. Note that the sclerotia can survive deep in the soil for up to 10 years.

If that’s not possible, consider planting in containers or raised beds, using fresh soil.

Sanitation

Make sure your gardening tools are clean!

Options include a solution of 10 percent bleach, 70 percent rubbing alcohol, or an activated oxygen product called BioSafe Disease Control that is available from Arbico Organics.

If you grow your tomato plants in containers, sterilize the pots before using them again. Plant in fresh soil to lessen the risk of possible infection.

Prevent Excess Moisture

If you can keep the surface of the soil dry, you have a good chance of preventing the sclerotia from germinating. Promote good drainage and prevent pooling of surface water around your plants.

Prune your plants to improve air circulation, and don’t plant your tomato plants too close together.

This combination of careful pruning and adequate spacing will reduce the amount of excess moisture that remains on the leaves, allowing it to evaporate more quickly.

Other techniques to minimize moisture include spacing your rows widely, and caging or training your plants to grow up trellises.

Finally, avoid watering your plants from overhead. It is best to use a soaker hose at the ground level, or drip irrigation, to avoid spraying water on the foliage.

Sterilize Your Soil

Commercial growers sometimes fumigate their soil. However, the chemicals used are highly toxic to all forms of life – not to mention expensive – so this is something that you probably want to avoid as a home gardener.

Some studies have shown that soil solarization for eight weeks during the summer months can be effective.

Solarization involves laying a transparent sheet of plastic over the soil surface to use the heat from the sun to raise the temperature of the soil. The sheet needs to be pulled tight to minimize air pockets, and weighted down at the edges.

Dig Up the Soil Around the Stem

If you are short on space and you must consider planting your tomatoes in the same plot next year, strongly consider digging up the soil after removing an infected plant.

Dr. Beth Gugino, Professor of Vegetable Pathology at Penn State University, recommends digging a circle around infected plants with a radius of six to eight inches four to six inches deep in the ground, and remove all of the soil.

Dispose of it in the garbage rather than reusing the soil!

Biofungicides

Other options include using biofungicides – treating the soil with microbes that will kill the S. sclerotiorum.

Your primary option is a certified organic product called Contans WG that contains a suspension of spores of Coniothyrium minitans, a fungus that parasitizes the sclerotia.

This strategy works best as part of an integrated pest management system.

You will need to plan three to four months in advance to give the fungus plenty of time to attack the sclerotia.

It is also critical to avoid tilling the soil deeply, or you risk bringing sclerotia buried deep in the soil to the surface, where they may pose a threat to your plants.

Fungicides

Several synthetic fungicides are registered to control S. sclerotiorum.

Endura (boscalid) is specifically labeled for gray mold, but is known to be effective against timber rot as well. You should apply it in advance if you suspect that an attack is likely.

Other options include Fontelis (penthiopyrad) and Botran (dicloran).

The Combination of Spores and Sclerotia Is Deadly

White mold (or timber rot) of tomato has multiple ways of spreading to attack your plants. Air can blow in spores or soil infested with sclerotia, which can then make more spores.

It is important to familiarize yourself with the early symptoms and keep a close eye out for this disease.

There are a number of cultural methods you can implement to reduce the chances of infection.

If you know your soil is infested with sclerotia, you can treat it with a biofungicide to parasitize and kill them. And you can preemptively use synthetic fungicides to prevent infection.

Now, armed with this information, you are better equipped to keep this destructive pathogen out of your tomato garden.

Have your plants succumbed to timber rot? Or were you able to fight back against the white mold? Let us know in the comments, so we can learn from your experience.

And for more information on identifying and treating common tomato diseases, you’ll need these guides next:

- Blossom-End Rot: What to Do If Your Tomatoes Rot on the Bottom

- How to Prevent and Treat Early Blight of Tomatoes

- Identify and Treat Septoria Leaf Spot on Tomatoes

- How to Prevent Southern Blight on Your Tomato Plants

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photo via Arbico Organics. With additional writing and editing by Clare Groom and Allison Sidhu.

This disease is realy disturbing it has kills more than hundred tomato plants please assist

Hi Bakari,

Your poor plants! I’m so sorry that you are dealing with such a horrible disease.

Most of the ways to manage this pathogen are preventative. However, the article does list several fungicides that you can use. Given the severity of the infection, I would strongly suggest that you try them.

I hope they work. Please let us know how your plants are doing after treatment.

I’m not 100% positive what killed this plant in a raised bed was timber rot, but digging up the dead plant showed an astonishing degree of dry white soil around the root ball. Is this consistent with timber rot?

What type of symptoms did the plant show before it died? Does the dry white material dissolve in water? And are you able to share photos?

Timber rot often exhibits cottony fungal growth aboveground, whereas the dormant fungal structures that form beneath the soil are black specks. What you may be seeing is the growth of saprophytic fungi which feed on dead plant matter. These do not typically cause disease in plants. Shallow, frequent watering could also potentially lead to salt buildup around the root zone of plants, but these salts would dissolve in water whereas mycelium will not.