Eriosomatinae

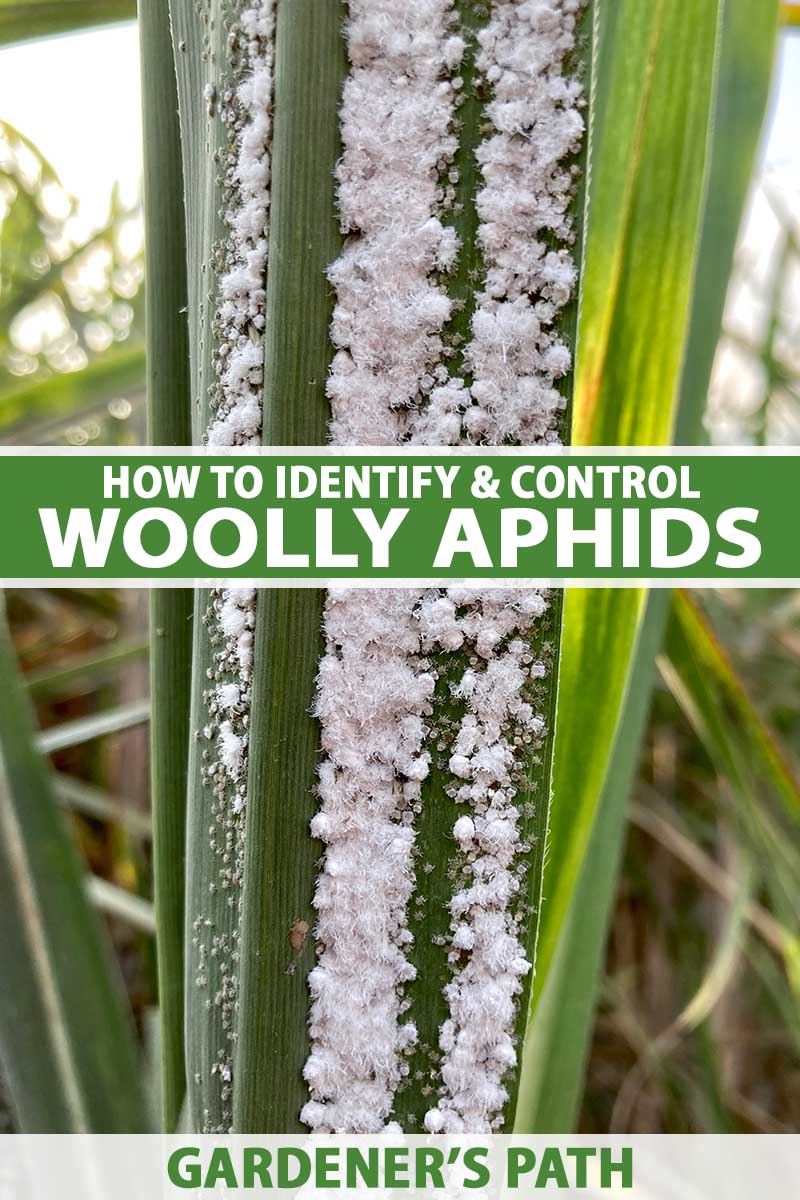

Just in case there weren’t enough white waxy insects for you to tell apart already, such as scales and mealybugs, here is another fluffy type.

Now introducing the shrub- and tree-loving woolly aphid, an insect that takes the waxy coating game to a whole new level.

Aphids are notorious plant pests, and the fuzzy types can be just as hard to identify by species – and sometimes even harder to control – than their smooth, shiny relatives.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

We’ve compiled everything you need to know about these sap-sucking pests, so you’ll know how to deal with them when they show up on your apples or landscape trees.

Here’s what we’ll cover in this guide:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Woolly Aphids?

Belonging to the Aphididae subfamily Eriosomatinae, these pests suck the sap from a variety of plants, especially trees and shrubs such as edible and ornamental apple, cotoneaster, maple, elm, alder, and beech.

They feed on both underground and aboveground parts of these plants, from the roots to the twigs and leaves.

This causes twisted and curled leaves as well as chlorosis, or yellowing of the foliage, and may result in reduced plant vigor.

Some species cause galls, which can provide entry points for fungal diseases.

However, the primary negative effect of these woolly creatures is cosmetic, and their main hosts are ornamental, so infestations of white fluffy insects are not appealing.

Like other sap-sucking pests, these insects exude sweet honeydew, which attracts ants, and an ugly black sooty mold can grow on stickied leaf surfaces.

Identification

Woolly aphids have three-millimeter-long, pear-shaped bodies that are covered in a white, waxy, fluffy coating.

There are several common species to look out for on your plants. Often, the host gives the best clues to help identify what species is attacking, as the insects themselves can look quite similar.

The woolly apple aphid, Eriosoma lanigerum, is a common and serious apple pest worldwide.

As its name suggests, it loves apples of all types, including ornamental crabapples, but it will also feed on elm, alder, mountain ash, hawthorn, serviceberry, and pyracantha.

These have bluish-black bodies under their white fluff, and they feed on the base of new shoots, branches, roots, and trunk wounds.

Their feeding causes galls to form, and these cracked and swollen areas on branches – perfect entry points for diseases such as rots and canker – are the primary reason these insects are such serious pests, and why they are sometimes called American blight aphids.

Woolly elm aphids, Eriosoma americanum, feed on American elm foliage in the spring, and the roots of serviceberry (also known as Saskatoon berry) as an alternate host in the summer.

On elms, feeding causes the edges of new leaves to roll inwards and form a gall-like swelling where they hide out. On Saskatoon berry bushes, especially young plants, root feeding can result in stunting and reduced berry production, and the damage can be fatal.

On the elm, the adult has a red-orange body with some white sticky bubbles, or it may be covered with a waxy cotton-like coating. On the serviceberry, where they are found underground, they are light blue to black, and may have some waxy fluff on their thoraxes.

The woolly alder aphid, Prociphilus tessellatus, feeds on silver maple in the spring, and alder in the summer.

This is the super fluffy species you may already be familiar with, and they look like pieces of cotton floating through the air when they’re flying, or fungi when they’re congregated on twigs. Even their eggs are woolly.

Besides looking a little strange or even ugly on the plant, this species doesn’t cause significant damage.

Large populations can cause shriveled leaves, and the honeydew they produce can make vehicles, sidewalks, and any lawn furniture positioned under the maple or alder trees sticky.

But these issues aren’t usually serious enough to warrant control.

Biology and Life Cycle

Most of the woolly aphids have two primary hosts, which they alternate feeding and reproducing on.

Often, they lay eggs on the primary host, the eggs overwinter in the cracks of bark, females hatch in the spring, and they begin to produce live offspring.

They will spend a few generations feeding and reproducing, without males, on the primary host plant.

A generation of winged females will fly to the secondary host soon after, and they will spend most of the rest of the season feeding and reproducing there.

In the late summer or early fall, a second wave of winged females head back to the primary host, and produce a generation of males and females.

These mate, and each female lays one egg that will overwinter and hatch in the spring, producing another all-female generation.

Some species will hatch before winter, and spend the season as nymphs on the host plant’s roots.

Females can produce hundreds of offspring during their one-month lifespan, and these offspring reach sexual maturity in four to ten days.

One of my professors described this as giving birth to live, pregnant young. Thus, populations can explode very quickly.

Monitoring

Keeping a close eye out for these pests before their populations – and the damage they cause – gets out of control is essential for effective management.

The downside is, once the damage is visible, management options are often limited or rendered ineffective.

Check the undersides of leaves for woolly aphid populations. Look out for shiny, sticky honeydew and an accumulation of waxy shed skins on the upper side of leaves.

They are easily mistaken for mealybugs and scale insects. But mealybugs often have tails, and both mealybugs and scales are flat while aphids are pear shaped.

Often, the distinguishing feature of aphids is the two tailpipes (cornicles) on the end of their abdomens, but they are short and often covered by fluff on woolly species.

Organic Control Methods

Control is not often warranted, especially on mature, healthy trees and shrubs. However, infestations of certain species, especially Eriosoma lanigerum, can become serious enough to bust out the control options.

If control is necessary, approach these pests with an integrated pest management (IPM) strategy, combining monitoring with cultural and biological methods for safe, effective control.

Cultural and Physical Control

Keep your plants healthy to achieve tolerance and minimize damage.

Avoid planting one host – elm, for example – near or in the same vicinity as the other host – such as serviceberry. Try to avoid cultivation of one host in the same area where wild alternate hosts are growing as well.

Physical control methods can be hard or impossible to use on tall trees, but on smaller trees and shrubs, you can use a strong stream of water from the hose or scrub infested areas with a stiff brush to dislodge colonies.

Prune out and destroy heavily infested twigs and branches.

These pests spread by crawling, flying, or being transported via plant material, clothing, gardening shoes, and tools, so examine new plants and clean your tools between working with infested and non-infested plants.

Plant resistant varieties of common host species. For example, ‘Northern Spy’ apples are resistant to the woolly apple aphid.

Biological Control

Parasitic wasps are the primary enemies of these pests in general, and they can often provide adequate control of small populations. Aphelinus mali, for example, specifically targets the woolly apple aphid.

Lacewings, ladybugs, hoverflies, and even earwigs will snack on them as well.

Aphidoletes aphidimyza is a commercially available predator commonly referred to as the aphid midge that can be applied and works well in indoor settings such as greenhouses.

The adults lay eggs near the aphids, and the resulting larvae prey on the pests.

Find these predators available at Arbico Organics.

None of these beneficial insects will target the underground pests, however.

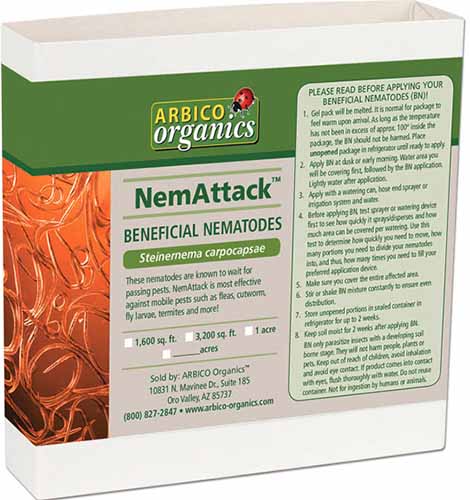

That is a job for the nematode Steinernema carpocapsae, which will attack underground colonies.

You can find these sold under the brand name NemAttack at Arbico Organics.

Learn more about how to use beneficial nematodes in our guide.

Organic Pesticides

Using pesticides to control these insects can be difficult, thanks to their protective waxy coating.

Good coverage and penetration of this fluffy coating is essential to achieve any effect with contact products, whether organic or chemical in nature.

Most of the products that are effective against smooth aphid types can provide some control of the fluffy types as well, provided coverage is adequate.

Horticultural oils, such as this one from Monterey that is available from Arbico Organics, and insecticidal soap products such as this one from Bonide, also available at Arbico Organics, are two viable options.

There are no organic or chemical controls available that are specific to the treatment of underground pests.

Chemical Pesticides

Chemical control is rarely justified with these pests.

As with organic contact products, chemical contact pesticides such as pyrethroids are not very effective against them either.

Systemic chemicals, those that are absorbed and translocated throughout the plant, are the most effective, as these are sucked up with the sap they feed on.

However, chemical applications can actually serve to encourage insect outbreaks, as these can be toxic to beneficial insects as well. Reducing or wiping out predator populations gives the aphids a chance to reach infestation levels again.

They are not choosy about pollinators either, so avoid using chemicals on plants that attract bees and other pollinators, and if you must use them as a last resort, wait until the plants have finished blooming.

Beware the Plant-Eating Cotton Balls

Though these insects can look like innocent bits of floating cotton, they can quickly settle into fluffy plant-sucking colonies.

Not only can they cause leaf curl or stem galls, they also don’t exactly create what you’d call a desirable aesthetic on ornamental trees and shrubs.

Luckily, the damage they cause is often minor, and nature provides some control to go along with your cultural and physical strategies.

Have you ever dealt with these downy insects before? Let us know down in the comments what plants they targeted, and how you controlled them!

And for more information about other plant-sucking insect pests, have a read of these guides next:

Hi, I have just discovered this on the branches of a climbing plant that we have. There does appear to be an infestation (if that is the right term). It feels slightly spongy and when I removed it from the branch there is an orange type ‘glue’. I am in Australia and it is winter. Can you tell me what I am dealing with. Thanks

Hey there, Vanessa! It doesn’t seem to be from a pest… do you know what species of plant it is? That could help narrow down the list of possible ailments.

White wax scale is the name of this pest. You can use Neem oil, fingers to remove them, white oil or a systematic poison if they can not be controlled naturally. I always get them in winter when it is wet. The ants carry them around the plants. I have a lot of trouble with them all the time. Good luck.