To me, pumpkins are the paragon of autumn, my favorite season. So this last winter, I decided to grow a few varieties indoors in early spring for a summer transplant into the garden.

But the gourds began to flower while they were still inside.

Frantic, I researched pumpkin pollination. Sure enough, they need bees in order to be pollinated.

Alas, there were no bees to be found in my house in early May.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

What comes next is a story of determined lovers, along with tips for what to do if your flowers aren’t as romantic as mine.

Ready to unlock the secrets of Cucurbit pollination? (Because yes, everything you’ll learn here applies to zucchini, squash, gourds, cantaloupes, and more.)

Here’s what you’ll discover:

What You’ll Learn

How Do Pumpkins Pollinate?

Before we get started on how to hand-pollinate your pumpkins, let’s dive into the nitty-gritty details of pollination for this gorgeous member of the Cucurbit family.

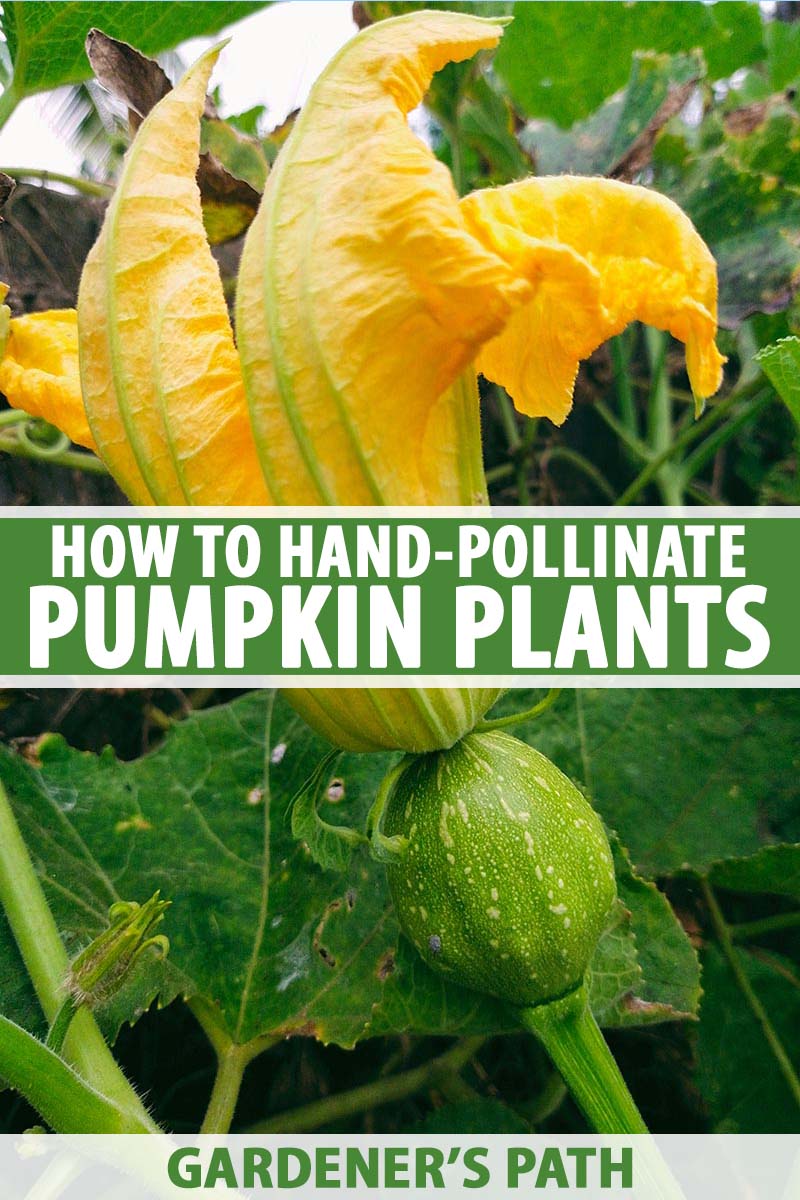

About 50-55 days after your seedlings germinate, the first yellow, open-throated flowers will appear.

These are the male, or staminate, blooms. They usually start blooming a week or two before the female, or pistillate, flowers. And unlike the females, they contain no visible teeny tiny baby – aka the ovary – at the base of the stem.

That’s right – pumpkins and other Cucurbits are monoecious, meaning they have separate male and female flowers on the same plant.

In order for the baby ovary to grow into a mature fruit, pollen from the male flower’s stamen must be transferred to every portion of the female’s pistil.

How does that typically happen? You guessed it. When your plants are growing outdoors, honeybees, bumblebees, and squash bees usually do that work for you.

But if you’re like me and you’re growing your gourds indoors for a while, you’ll have to do it yourself if they bloom. We’ll talk more about that in a moment.

Here’s a tip: don’t be like me and freak out when both the male and female flowers wilt and die by the end of the day.

That’s what they’re supposed to do. The ideal pollination time is during those golden hours when both types of flowers are open.

While one plant can definitely have both male and female flowers blooming at the same time, you’re more likely to get more “pollination windows” if you plant several gourds of the same variety.

This is because there will be more male flowers open at a given time to pollinate those females.

But say you don’t have many bees around in your outdoor garden, you’re growing gourds in a greenhouse or a similar indoor space where bees don’t have access, or it rains on the day when your male and female flowers open and the bees aren’t out and active?

This is where hand pollination comes in.

Or romantic intentions between blooms, if you want to place your bets on it…

That’s what happened to my ‘Jack be Little’ plant.

A Tale of Determined Love

One morning, before I had researched how pumpkins are pollinated, I awoke to find a flower with a tiny baby pumpkin at the base (aka the female flower) and another flower from farther down the vine fused together in what appeared to be a sort of embrace.

A couple days later, the blooms fell off but the baby remained.

And it kept growing.

After conducting my research into pollination, I was fascinated to discover that the two blooms had somehow found each other, with the male pollinating the female directly since there weren’t any bees inside and I, the tardy gardener, hadn’t solidified my pumpkin pollination knowledge yet.

Isn’t that too cool?

If you don’t want to depend on this unlikely but seemingly amorous method, here’s what to do.

How to Hand Pollinate Pumpkin Plants

The easiest way to do this is to first identify a male flower. The stamen should be covered with fuzzy pollen.

Next, peel back the petals until the stamen is exposed. Take the stamen and bring it over to a female flower’s pistil, which looks like this:

Gently rub the male’s stamen over each segment of the female’s pistil until there’s plenty of sticky pollen on every single segment.

You can also take a paint brush or cotton swab and use it to gather yellow pollen from the male flower.

Then, carefully brush the pollen all over the female’s pistil.

Once you’re done, gently seal the female flower by pressing the petals together, covering the pistil. This will keep any nearby bugs from landing there and transferring pollen away from the flower.

That’s all there is to it.

The female flower petals will dry up and fall off, and the tiny ovary will grow into a fat pumpkin if it’s been pollinated sufficiently.

An Easy-Peasy Path to Beautiful and Delicious Harvests

It’s shocking how easy it is to pollinate pumpkins on your own. Now that you know, you can be smarter than I was, and watch out for those male and female flowers.

Now even those of us who have to grow our gourds somewhere artificially warm and bugless can enjoy the promise of pollination.

Have you ever hand-pollinated Cucurbits? Let us know in the comments below!

And don’t forget to check out these guides for more information on growing pumpkins in your garden:

Hi Laura! Thank you for this post! I’ve tried to pollinate TWO females within the past week and they’ve both shriveled up. I followed every single thing I’ve learned and they still didn’t make it. I searched again for more info ( which is how I’m here now) because I have another female probably about 7 hours away from opening. I have alarms set in hopes it opens a bit early! LOL! I only have 2 giant pumpkin plants and ONE male flower about to open (@ the same time as the female). There was a male flower that boomed… Read more »

Hi Jen! I’ve had a pumpkin shrivel post-hand pollination too. The next time, I used flowers from two males, and that was a success! I now have a fat Howden growing after a shriveled miss last month. So I’d say, go ahead and use the saved flower and the one that’s open.

Best of luck!

I have read that there is only a short amount of time for pollination to occur. Time being four to six hours. Have you found this to be true?

Also, I have about six beautiful blooming vining pumpkin plants, but alas ALL of the blooms fall off without even one single little pumpkin. I have absolutely no clue as to when the best time to hand pollinate is. Any help there is appreciated.

Thanks so much for your article.

Kay

Hi Kay! The best time is typically in the morning, but any time during their one-day “open period” is fine. The flowers tend to shrivel by late afternoon or evening. Get out in the garden early every morning and you should be able to catch them!

Hi! This spring we started getting these weeds with GIANT leaves!! (Tells you what I know about gardening!) It took a bit before I remembered, we left the GIANT pumpkin we were goinggggg to carve there after it sat on my kitchen table for about 3 weeks after Halloween ???? Well, I’ve been watching it and reading up on them and just used this article to hand pollinate it as it just so happens I do have a female and 2 males in full bloom this morning!! I used both the male flowers to be sure it got plenty of… Read more »

I’m looking at my first time pumpkin garden wondering why I have so few growing even though it’s a big and healthy bunch of plants. This article may just save the pumpkin patch! Thank you for such easy yet thorough tips!!

You’re welcome Heidi! Let us know how it goes and feel free to reach out if you have any questions.

Pumpkin fertilising I have done this lots of times. Usually by breaking all petals off male flower & wave over girl flower bits. Sometimes leaving the male flower embeded in girl flower. As vine is growing I keep an eye on flowers that are likely to open on same day. I like to fertilise them early in the morning while flowers are nice & fresh. You will know within a couple of days if it has been successful. If so, they will grow fast. I grew my last lot on a Trellis, had to make hammocks to support the fruit.… Read more »

Good morning! What do you do if you have three male flowers and no females yet? Can the male flowers be picked and saved?

Male flowers tend to appear first early in the season, but this shouldn’t be a cause for worry. As long as the environmental conditions are suitable, female blooms will appear as well in time. You could try storing pollen in the freezer if you wish, but this shouldn’t be necessary.

Ok my question is. Let’s say you didn’t get home from work till about 3pm and the flowers have opened and closed while you were gone. Is it possible to hand open then back up and then pollinate them yourself? Closing them back up when you are done. I haven’t had much bee activity in my small pumpkin patch (have had a few vine borers). I would like to be absolutely positive things got pollinated.

Hello Matt! I hate that you don’t have an ideal window of opportunity for hand pollinating given your work schedule. Any chance you can try that on a few of the flowers and let some others go to cover all your bases? Also, is it possible your pumpkins are planted somewhere near grass or other plants treated with pesticides? Of course, your very best bet is always going to be to encourage the pollinators to do the pollinating. Strategies there include planting native flowers and possibly providing mason bee houses. You can read more about applying pesticides and insecticides in… Read more »