Trivia buffs and riddle lovers can take a break today, because the answer to the question, “What’s the difference between a lima bean and a butter bean?” is… nothing.

Both are just different names for the tasty legume Phaseolus lunatus.

But that’s not the complete story. Sometimes home gardeners will find it relevant that a bean has one of these labels or the other, especially in particular areas of the country, or the globe.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

At the same time, when you shop for seeds or decide which variety to plant in your garden, it’s important not to let the lima-versus-butter-bean confusion influence your choices.

Instead, focus on the important distinctions for any lima or butter bean variety you might grow. I’ll share the top three here, and cover these other topics, too:

What You’ll Learn

The Difference Between Lima and Butter Beans

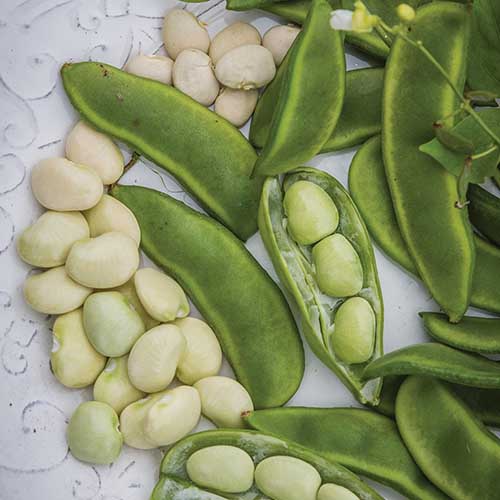

They may look alike, whether you view them in bags of dried heirlooms, on canned goods’ labels, or if you’re one of the fortunate few who spots them shelled at a farm stand.

But one is called “butter bean” and the other “lima.” What’s up with that?

Mostly, a regional tendency to nickname our favorite veggies is at play. These two common names both apply to Phaseolus lunatus, and are used interchangeably as umbrella terms for its many cultivars.

So, yes, lima and butter beans are the same thing. They both require a warm-weather, frost-free growing season, and produce seeds that can be cooked fresh or dried. And neither has edible pods.

With that said, though, sometimes people in a certain region do mean something specific when they use one name or the other.

P. lunatus includes a variety of beans of different sizes. Some of the larger seeds can be as wide as an inch and a half, and the smallest can be about the size of your pinky fingernail.

In some areas, the big ones are called “butter beans,” while in others, they’re known as “limas.”

The Brits, for example, are in the “big equals butter” camp, referring to most all P. lunatus cultivars as butter beans, but especially the ones they describe as being large and starchy.

Maybe they have recognized that these are delicious served with a pat of butter on top, much like a fresh-baked, homegrown potato.

In the American South, people usually call all of them “butter beans.”

If you’re offered a dish of them at an old-school diner, you can expect any variety, but you should assume they’ll also be cooked with some sort of pork or smoked meat (and that they’ll be delicious).

But it’s also common in the South to call the bigger ones limas and reserve the butter bean moniker for “baby limas,” the ones with the smallest seeds.

I take as my authority on this matter “Marion Brown’s Southern Cook Book,” compiled from exhaustive correspondence with Southern home cooks and well-known chefs, and published in 1951.

It’s available on Amazon if you want to snag a copy of your own.

Marion Brown’s Southern Cook Book

Brown ascertained, “The lima bean is larger and more mealy” but could be cooked in the same manner as butter beans.

For either, she recommended boiling two cups of fresh shelled legumes until tender, draining, and then dressing them with a lump of butter, a teaspoon of sugar, and a cup of cream or milk, if desired.

It may be a stretch to compare cooked baby limas to my favorite dairy product, but these small-seed types are velvety, even sort of buttery, when sauteed or even slow-cooked.

The maroon-splashed ‘Jackson Wonder’ is an example of this type, and seeds are available from True Leaf Market.

Now, don’t expect anyone from the United Kingdom to have “lima” in their legume vocabulary, or for Southerners to call anything but a large, pale P. lunatus seed a lima.

But veer away from either of those groups, and you’ll find that many people take the opposite tack, calling all of the many varieties limas, a nod to the species’ origins in Peru, where it’s been grown for around 7,500 years.

These legumes were domesticated in different areas of Mexico 500 to 1,300 years ago, and it was there that the smaller seed varieties were developed.

In 1907, Burpee introduced ‘Fordhook,’ which took just 70 days to mature and allowed those in colder climates to begin growing this type of legume.

Early advertisements referred to them as “limas,” and Burpee still categorizes them that way, with nary a mention of butter.

Other Names for These Legumes

The many common names and colorful nicknames for certain vegetables, particularly legumes, are one of the things I really love about growing my own food.

P. lunatus offers an abundance of these titles, well beyond the two most common ones we’ve discussed here so far.

One name that crops up fairly often is “potato bean,” for the big white seeds that have a baked potato texture when boiled or steamed.

This type of legume is also known as a “Burma bean,” probably because it’s often grown there.

“Sieva” or “Carolina” beans are two more that you might hear, particularly in the South.

These names probably came into common usage thanks to the cultivar ‘Sieva Carolina.’

It was grown at Thomas Jefferson’s plantation Monticello (which, by the way, is in Virginia, not either of the Carolinas) in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Jefferson’s agricultural mentor Bernard McMahon mentioned it and shared specifics on creating poles to support hills of these “running Carolina lima beans” in his 1806 book, “The American Gardener’s Calendar.”

That particular type is a cold-resistant vine that produces white seeds. But in casual conversation, the names “Carolina” and “sieva” can apply to other cultivars, too, particularly those that produce small white seeds.

Other popular cultivars have also spawned nicknames that have come into common usage for broader categories of P. lunatus.

Some gardeners and diners refer to all vining limas as “Madagascar beans,” though according to the Australian seed company Succeed Heirlooms, the name is specific to a cultivar with large speckled seeds grown as perennials in hot, dry climates.

Adding to the confusion, the label “Madagascar bean” is also often used to describe vanilla beans grown in Madagascar.

Vanilla planifolia is an orchid species that produces seed pods. It originated in Mexico, but the Madagascar-grown version is lauded for its high vanillin content. It is not, however, a butter bean.

“Calico bean” is another nickname you may come across. It began as an alternative name for the ‘Christmas’ lima, a vining cultivar that originated in Peru and made its way to the US in the 1840s. It produces mottled maroon and cream-colored seeds.

Nowadays, the term “calico” might loosely refer to any number of speckled, spotted, splashed, or freckled limas. Or it might be a pale white butter bean, or even a baby lima, that’s being used in a recipe for “calico beans.”

The ingredients in this particular stew may vary, but is essentially a medley of browned ground beef and canned kidney beans, canned pork and beans, and canned P. lunatus, sauced up with store-bought ketchup and brown sugar.

I was intrigued when I discovered that the calico bean recipe presented by Johanna Christenson, a student intern at the North Dakota State University Extension Service, called for butter beans, and this referred to the large, white, mealy type.

Shall I go on? I can, you know! This may be the most prolifically nicknamed legume of all time.

Other names include Cape peas, and Chad, civet, Guffin, Haba, Hibbert, Pallar, pocketbook, or Rangoon beans.

And I have one more, my favorite, which I have never actually heard spoken out loud but read of recently: mule ears!

Yep, it’s a Southern label, from the same people who bring you the name “goober” for peanuts and say that wilted greens have been “kil’t.” I love it, and all the zany descriptors that have emerged from my area of the country.

Doubtless there are many more monikers, since this legume has been domesticated since before 5,000 BC. It’s fun to think about all the nicknames assigned to this one vegetable garden crop across seven millennia.

Are Butter Peas Lima Beans?

Now that we’ve cleared up the confusion, you’d probably like to leave it there. But for the sake of all that’s tasty, I must add one more variety to this conversation: butter peas.

Even though they’re not often grown outside the American South, I think they should be, because they’re prolific, full of green vegetable flavor, and so velvety when cooked.

And they’re also a type of P. lunatus, producing little morsels on two-foot bush plants. Butter peas are distinctly round, with seeds that resemble an undersized gumball. These become buttery when steamed, boiled, or stewed.

They take from 70 to 78 days to produce fresh pods for shelling.

This makes it possible to grow these in some shorter-season vegetable gardens, especially if you sow them indoors in biodegradable peat pots and transplant them out after all danger of frost has passed, pot and all.

If Southerners weren’t already referring to them as butter peas (even though they are not a type of Pisum sativum or garden pea), I have no doubt they would label these as mini butter beans.

And I can assure you that they’re worth considering if you’re looking for a high-protein garden crop that’s hard to track down fresh at the farmers market, or, well… anywhere.

This leads us to the next topic, which is this: if you’re not going to fret too much about which common name is used to refer to these legumes, what should you focus on?

Coming up, I’ll share the top three important distinctions to make when you select a variety to grow in your garden.

Spoiler alert: While you’ll want to know the name of the cultivar you plan to grow, I’m going to recommend that you not spend another second worrying about whether to call it a butter bean or lima, even if you’re Peruvian or hail from Mississippi or Texas, or somewhere like that.

Call them what you like, and enjoy them!

3 Traits Are More Important Than the Names

Want to grow these whatchamacallits? I’m so glad.

While you don’t have to take sides on calling them by the Southern term or the Peruvian capital name, or any of their many alternate titles, it is a good idea to consider these three things before making your selection:

1. Taste Profile

If you’re going to grow limas for fresh eating, drying, or freezing, you’ll want to pick a type that will taste good to you, and perhaps the other diners in your household as well.

The varieties with larger seeds in the pods tend to be earthy, with a starchy texture.

Notice I don’t say mushy, because they are nothing like those overcooked, bitter, and yes, mushy frozen legumes you might have consumed in your younger years.

Though they’re bigger, the larger-seed varieties tend to hold their shape better during cooking. If you’re envisioning making lots of soup, cassoulets, or chilled salads, opt for a large-seed variety.

If you’re pursuing a velvety texture and more of a green vegetable flavor instead of a “beany” taste, the types with smaller seeds, or “baby limas,” might be more your thing.

Note that the “baby” term refers to the variety and its tot-size seeds, not an immature variety of larger-seeded limas.

And remember that those smaller morsels tend to disintegrate during long cooking. So while they’re great for making a rich, silky hummus or a succotash with corn and ham, they’re not at all the thing for stews or casseroles.

‘Henderson’ is one such variety of baby lima, an early, drought-tolerant bush type. It produces seeds that are about a third of an inch long, pale green when fresh and bright white when dry.

‘Henderson’ seeds are available in packets and in bulk sizes up to 25 pounds at True Leaf Market.

2. Bush vs. Vine

As a home gardener, you always want to know how much space a given variety will take up in your garden, and whether it will need support.

For limas, it’s easy to get distracted by a catchy cultivar name (or the promise of buttery flavor!) and forget to check whether you’ll be growing a vining (aka pole or climbing) or a bush type.

I can confirm that varieties that grow aerially can save space on the ground, but bear in mind that some of those types also grow 10 to 12 feet tall, and need super strong supports.

My ‘Christmas’ limas are one example. The photo above shows just the top half of the vines where they have grown a good yard taller than the seven-foot arbor that supports them.

As for the bush types, they don’t need support and are usually better suited to growing in containers.

But you typically can’t grow as many of them if you have limited garden space, and they may not yield as much of a harvest as their pole variety relatives.

3. Days to Maturity

Call them what you will, but resist the urge to select one of these legumes to grow without first checking out how many days it will need to mature.

That “no frost” growing requirement is not a suggestion to be taken lightly. So be sure to opt for a fast-growing bush type if you have a super short growing season.

Keep in mind that limas require frost-free days from sowing (in warm soil) to harvest.

When you’d like to have a harvest to dry for next year’s seed or the winter panty, make sure to allow enough time for them to reach the stage where the pods are brown and brittle ahead of the first frost.

The pole varieties do tend to take longer to grow, often as many as 85 to 100 days to harvest after sowing. But they will reward you with a longer harvest window to offset the waiting.

If you have a longer growing season but like the idea of growing a bush type, you can always plan to plant in succession.

I Can’t Believe It’s Not Lima!

I kind of have to laugh at myself for my attitude here.

Usually, I’m such a stickler, complaining when people confuse favas and edamame, for example, or if they show me a photo of yard-long beans when I asked for black-eyed peas.

But for these, I make an exception, because I’m so intent on leading more people to grow this delicious, high protein, oft-overlooked legume.

If you can find one to plant that you’ll enjoy at harvest time, I honestly don’t care what name you call it. Great Southern Bush? Rhett Butler Runners? Margarine? All good by me.

What about you? Have you grown one of these, or heard of a name I haven’t mentioned? We’d love to hear from you in the comments section below. That’s also the spot for questions.

And if you’d like to learn more about the many wonderful varieties and how to grow a bumper crop, I’d recommend reading these lima bean guides next: