Psila rosae

It takes some work and patience to grow a perfect crop of straight, beautifully orange, smooth skinned, crisp and delicious carrots.

The soil needs to be crumbly and deep, they need water and fertilizer, and there are a variety of insects that might insist on having the first munch – not the least of which is Psila rosae.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Also known as the carrot rust fly, the maggots of this tiny fly are no joke. Thanks to their small size and well-hidden feeding, their damage can be an unpleasant surprise at harvest time if you aren’t keeping a close watch on your plants.

How can you deal with these hungry maggots?

Everything you need to know about them is laid out for you below!

Here’s what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Carrot Rust Flies?

Also known as the carrot root fly, the larvae of the this pest loves – you guessed it – those sweet, crisp, orange garden staples.

They will also attack celery, celeriac, parsley, parsnips, and other Apiaceae (aka Umbelliferae) plant family members, chewing on the roots.

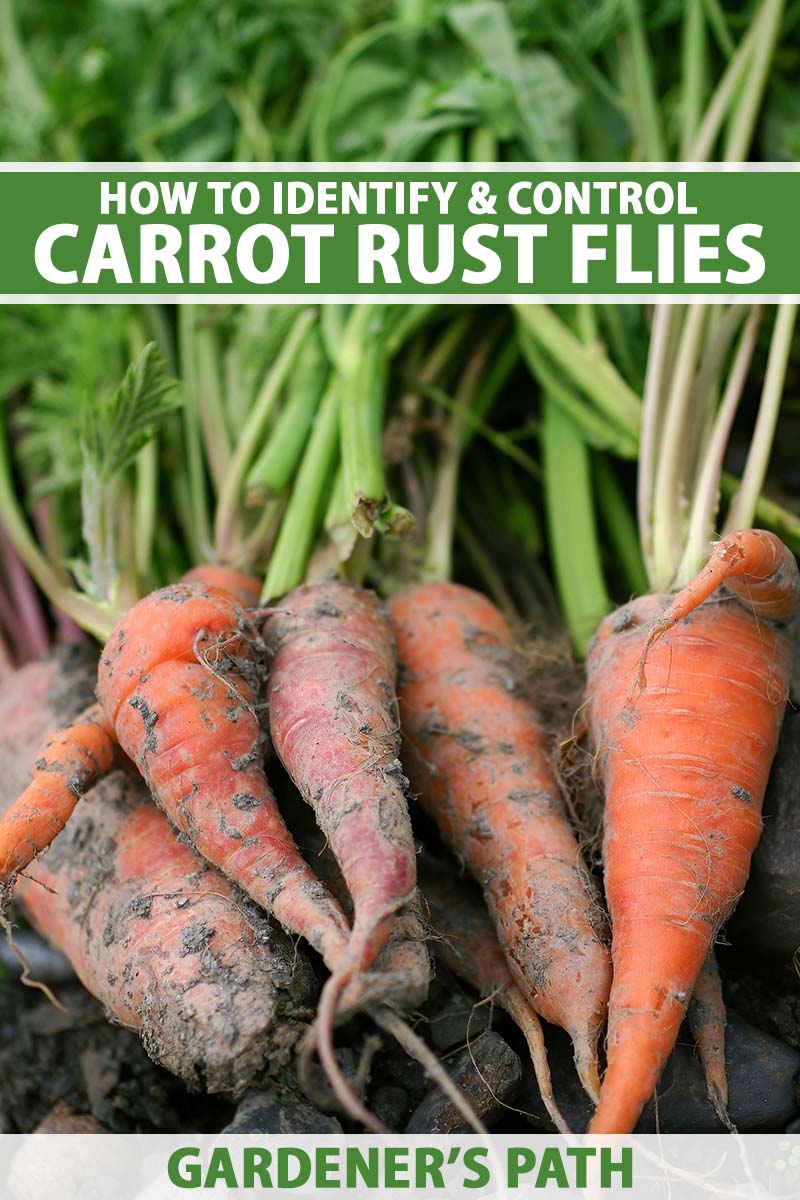

Symptoms of an infestation include yellowing and dying leaves and plant dieback, wilting, stunting, bulbous and forked roots, and root tunnels.

Older plants may be able to take some feeding, and will only show some root scarring, but these pests can kill younger plants.

The tunnels they mine turn rust red in color from the frass left behind by the immature pests, and these double as an excellent entry point for pathogens.

Identification

The adults are small, six-millimeter-long shiny flies with a dark-colored abdomen and thorax, clear wings, and an orange-tinted head. They are weak fliers.

The larvae are stiff, white to yellow-brown maggots that grow to eight millimeters long.

Eggs are white and about half to one millimeter long.

Biology and Life Cycle

These pests overwinter as pupae in the soil close to recent host plant crops or weeds, or as larvae in carrot roots left in the field or garden.

Adults emerge in late spring when it is still cool and moist. They will spend most of their time in the peripheries of the plot, usually only flying in to lay eggs.

Each female can lay up to 40 eggs in clusters of up to three eggs each, on the soil surface near the base of the plants.

Within 10 days the eggs hatch into larvae, which enter the roots. They will typically chew the lower portion of carrot roots, and the upper portion of parsnips.

The maggots feed for a few weeks before pupating in the soil for up to 25 days and emerging as adults. Second-generation larvae are often actively damaging carrots by August, and one to three generations can occur per year.

Monitoring

Commercial farmers often use yellow sticky cards at the soil level to monitor for adult fly activity. You can pull a root here and there in your garden to check for damage as well.

Organic Control Methods

In this section you’ll learn there are several non-chemical methods for preventing and controlling these crop-ruining pests.

Cultural and Physical Control

Control the alternate host weeds, such as hemlock, wild carrot, and other umbellifers surrounding the garden to reduce overwintering sites.

For the same reasons, clear out any crop residue at the end of the season, and rather than harvesting a carrot here and there, harvest entire plots at a time.

Since overwintering is accomplished near the host plants and the adults are weak fliers, use crop rotation strategies to avoid planting in the same spot as the previous season. This should help you avoid the majority of the first hatch the following year.

If you live in an area where carrots can tolerate summer temperatures, delay planting until after when most of the first-generation adults will have died, which could be in mid-June.

Exclude the adults from laying eggs in your crop in the first place by covering the plants as soon as they emerge or earlier with floating row covers.

Studies show that intercropping with dill, onions, marigolds, and calendula can help to reduce P. rosae damage.

Biological Control

Both hoverflies and ladybugs will attack these pests, so planting flowers to attract these beneficials not only looks pretty but is useful too!

Chorebus gracilis and Loxotropa tritoma, species of parasitic wasps, are used as biological controls in Canada.

Organic Pesticides

There are a few pesticide options for home gardeners, however, most have limited effectiveness. The adults are tiny, difficult to see, and hard to catch with sprays. The maggots are well protected in the soil and roots.

Spinosad – in formulations such as Monterey Garden Insect Spray, which is available at Arbico Organics – can be applied to the plants once you see the larvae for some control.

Chemical Pesticide Control

Chemical pesticides are used by commercial growers. They will often use a granular product added to the furrows during planting, and a pyrethroid sprayed for adult control during the growing season.

In your home garden, chemical pesticides often do more harm than good. They can be hazardous to beneficial bugs, pollinators, birds, and other living organisms, as well as soil, air, and water.

Pain in the Carrot

It’s the worst feeling when you are happily pulling your crop expecting beautiful, long, orange roots only to find frass-filled tunnels throughout the gnarled, stunted roots.

Sometimes the damaged portions can be cut or peeled off, leaving some edible bits, but that’s not the bountiful harvest you were anticipating when you carefully prepared a soft bed for the seeds in the spring.

Instead of merely hoping this pesky little fly won’t find your patch, employ the various methods we talked about above to put the odds in your favor.

Have you ever had issues with P. rosae maggots in your garden? Let us know how you got rid of them by sharing in the comments below!

While you’re at it, read up on more of the ins and outs of growing carrots here:

We have found that using boiling water in the fall after harvest, over the area where the carrot fly has done dammage has helped.

I keep seeing them emerging from the soil and a mash them. Not helping much.

Ugh, sorry to hear that Linda!