Buxus spp.

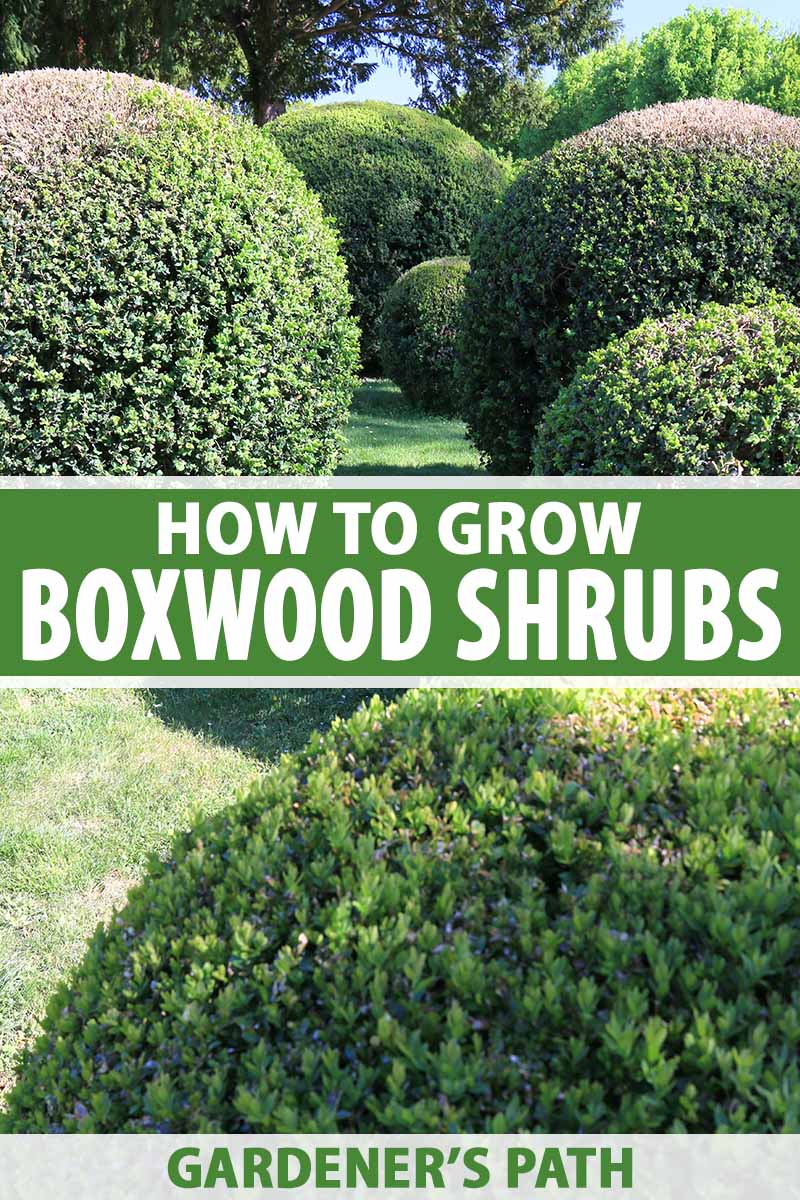

If you’re looking for a plant that’s terrific for topiaries, great for hedges, and even attractive when left untrimmed, the boxwood shrub is perfect for you.

A long-time favorite of Southern gardeners, boxwoods have been grown in the States for centuries.

In fact, you’ll find many of these shrubs growing on historic estates, including Middleton Place in Charleston, South Carolina, a National Historic Landmark and home to the oldest landscaped gardens in the US.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

What many people don’t realize, though, is that there are multiple types of boxwood you can grow – many of which are cold-hardy and can be cultivated by northern gardeners, too.

With 97 species in the Buxus genus and over 260 cultivars to date, according to the American Boxwood Society, there are, of course, certain varieties that are more popular than others when it comes to landscaping.

While many of these are only hardy to Zone 6, some can survive in temperatures as cold as -35°F (that’s Zone 3, folks!).

Whether you’ve been putting off planting boxwood shrubs because you think your growing zone is too cold or because you think these plants are too difficult for a novice gardener to care for, it’s time to give them a second look.

Keep reading to learn how to grow this beautiful shrub with gorgeous year-round appeal.

What You’ll Learn

\What Is the Boxwood Shrub?

Boxwood is a plant that is used in traditional landscaping designs all over the world.

It often grows to a mature height of 10 to 15 feet, depending on the species and cultivar.

But since it is so easily pruned, it can be grown as either a small tree or a wide-spreading shrub. It produces dense, evergreen foliage with leaves that are typically dark green on top and a yellow-green underneath.

There are several species that are popular among gardeners, including the common or American boxwood (B. sempervirens), of which the English type is a variant, and the littleleaf or Japanese boxwood (B. microphylla), of which the Korean type is a variant.

As their common names suggest, B. sempervirens is what you will see growing most commonly in the US, while B. microphylla has notably smaller leaves and a smaller stature to match, generally only reaching a mature size of four feet by four feet.

This makes cultivars of B. microphylla a good option for gardeners with limited space. We’ll cover a few suggested varieties of both species in the cultivars section below.

Both species grow slowly, adding fewer than 12 inches of growth each year. While Japanese boxwood tends to be more heat-tolerant, American boxwood is often better for northern growers who live in regions with cold winters.

Curious about the term “boxwood?” The reason for this moniker is quite simple: The wood from these shrubs is well-suited for carving and woodturning.

It’s often used for projects like making chess pieces, musical instruments, rulers, and other small specialty items. Quite literally, the name of the genus – Buxus – simply means “box” in Latin.

Boxwood shrubs produce small yellow-green flowers in the spring, but these are not usually noticeable.

They also produce tiny fruits that contain small seeds. While these are attractive to birds, they aren’t a major draw for most gardeners.

Instead, these shrubs tend to be grown for their glossy green foliage, which remains evergreen throughout the year.

Cultivation and History

Boxwoods are native to western and southern Europe, and portions of Asia, Africa, South America, Central America, and the Caribbean.

As stated above, though other species are grown in gardens in other parts of the world, it’s B. microphylla and B. sempervirens that are most commonly cultivated in the United States, as they do not require tropical growing conditions to flourish.

These plants have a long history in cultivation. Ancient Egyptians planted boxwoods in their gardens and trimmed them down into formal hedges as far back as 4000 BC.

And members of other cultures used the wood for making musical instruments, rulers, and other small objects for which larger types of shrubs and trees were not appropriate.

B. microphylla has been cultivated in Japan since the 1400s. Believed to be the result of hybridizing other species in the garden, it’s unclear which specific species may have been used.

B. sempervirens was first introduced into the US in the 1600s, after being brought by Anglo-Dutch merchants from Amsterdam to Long Island, New York.

Boxwood is unique in that it is an evergreen species that can also be used in medicine, with historic use in treating rheumatism, epilepsy, toothaches, and fevers, particularly in its native range in Asia and the Americas.

Curious about how to grow these shrubs in your backyard? Keep reading to learn more.

Boxwood Propagation

There are three ways you can grow a boxwood shrub: from seed, from a cutting, or from a started transplant. We’ll cover all three methods below.

While it’s certainly possible to start from seed, a transplant is by far the easiest avenue for a novice gardener.

Growing these shrubs from seed will take some time, as does rooting a cutting – but both are fun projects if you’re willing to give them a try!

From Seed

First, you will need to purchase a soilless mix to germinate your seeds. Plants grown from seed are generally less uniform than those grown from cuttings, and you’ll need to first cold-stratify the seed.

This involves exposing the seeds to one to two months of cold temperatures.

You can do this by using a bit of sandpaper to scratch the coating of the seeds. Soak them overnight in warm water, then drain the seeds and place them in a plastic bag filled with damp peat moss.

Refrigerate them for about four to eight weeks at 33 to 41°F, depending on the species, and make sure they neither dry out completely nor become waterlogged.

Once they’ve been cold-stratified, you can plant them about one-sixteenth of an inch deep in a large seed-starting flat filled with moist seed-starting mixture. They should be planted about three inches apart.

Cover the container with plastic wrap to produce a greenhouse effect, and keep the soil moist by spraying the surface with a spray bottle a few times a day.

Boxwood seeds take a long time to germinate, up to six months in some cases.

If you start them indoors towards the end of spring, or in a warm location like under a cold frame or in a greenhouse, plan to care for them there through their first winter.

They can then be planted out in the late spring the following year.

When the seedlings appear, you can remove the plastic wrap and place them under grow lights.

You can also put the seedlings next to a sunny window, but a grow light will provide more consistent light and help prevent them from becoming “leggy” as they reach for the light.

Water daily, keeping the soil moist but not sodden.

When the seedlings are about four inches tall, you can thin them out and transplant the strongest ones into individual pots that are approximately six inches wider than the root ball of each plant.

From Cuttings

Many people choose to grow their boxwood shrubs from cuttings. Though not as simple as planting seedlings or small shrubs from the nursery, it’s still an easier option than starting your plants from seed.

To do this, first you will need to obtain a cutting. Generally, the best time to do this is sometime in the late summer to early fall.

Wait until after spring growth has hardened up, then choose a healthy, strong branch with no signs of disease.

Take a cutting that is approximately four to six inches long. Strip the leaves from the bottom half of the stem, then dip half an inch into powdered rooting hormone.

Place your cuttings about two inches deep in a potting mixture of equal parts compost and sand. Use a pencil or stick to keep the plant upright and stable.

The container you use should be at least four to six inches wide and equally deep.

Then, put your cutting in an area that’s warm and receives plenty of sunlight. Keep the soil moist, and mist the foliage with a spray bottle once or twice a day to keep it hydrated.

After four weeks, check to see if your cuttings have formed roots. You can determine this in several ways. Usually, if the cutting hasn’t wilted and died by this point, there’s a good chance that roots are present.

You’ll know the roots are strong if you can lightly tug on the cutting and it sticks. If it remains firmly stuck in the soil, you have roots.

If that’s the case, you can transplant them into larger containers about two weeks later. You can transplant outdoors in the spring.

From Seedlings or Transplanting

Of course, the easiest way by far to grow a boxwood shrub is to plant a seedling or nursery transplant.

Boxwood shrubs can be grown in just about any light condition, tolerating heavy shade to full sunlight. A blend of the two is best, ideally in a location that provides dappled sunlight or light shade with a few hours of morning or early afternoon sun.

Plants that are grown in full shade are generally less vigorous, while those grown in full sun are susceptible to leaf scorch.

Dig a hole that is as deep as the root ball and twice as wide, using the container the transplant came in as a guide.

Remove the plant from its container and gently loosen its roots. Then, place it in the hole until you can see about two inches of the root ball above ground level.

Boxwoods root shallowly and should not be planted too deeply – the top eighth of the root ball needs to be set above the soil level.

After planting, water thoroughly, as this will help your plant set strong roots. Add two to three inches of organic mulch, which will help keep the roots cool and to conserve water.

How to Grow Boxwood Shrubs

Plant your boxwood in well-draining soil. Before planting, conduct a soil test to make sure your soil is mostly neutral, with a pH between 6.5 and 7.5.

You can add compost or other amendments as indicated by your soil test before planting, if necessary.

Water thoroughly and frequently if you receive less than one inch of rainfall per week. You can determine the amount of precipitation your garden has received with a rain gauge.

Fertilizing is not always necessary for these plants, but if a soil test determines that your soil is deficient in certain nutrients, you may want to start a regular fertilization schedule.

Boxwood plants, known for their foliage, are also prone to nitrogen deficiency. If that’s the case, you’ll notice that your plants’ lower leaves have begun to yellow or fall prematurely from the shrub.

You can apply a liquid all-purpose 12-5-9 (NPK) fertilizer in the early spring, applying it liberally around the base of the plant.

Growing Tips

- Grow in moist, well-draining, loamy soil

- Apply one to two inches of mulch

- Thin plants regularly to improve air circulation

Pruning and Maintenance

These shrubs should be pruned to encourage branch development and to maintain a desired shape.

The best time to prune is in early winter. Prune only small amounts, cutting off no more than a third of the plant at one time.

If more widespread pruning is needed – for example, if your plant is suffering from a disease – you should start by cutting large branches on just one side of the plant and then taking the other half the following year.

This will prevent you from overstressing the plant when it’s already trying to recover from another event or condition.

You can also thin your boxwood shrubs to improve airflow. This should be done once a year, any time when temperatures are above freezing.

You can read more about pruning boxwood shrubs here.

Mulching is a good idea for most plants. Adding about one to two inches of organic mulch, like pine needles, composted leaves, or pine bark, out to the drip line will help keep the soil moist and fertile.

Just avoid pushing mulch against the stems, which can lead to rot.

Boxwood Species and Cultivars to Select

When shopping for boxwood species and cultivars to grow, remember that your growing zone will play the biggest role in your selection.

Here are the top two most popular species, with corresponding recommended variants where applicable, and cultivars to choose as well:

Common

The American boxwood, B. sempervirens, is the most common species found in the United States. In fact, it’s often referred to simply as common boxwood.

Often used in hedges, it can grow up to five feet tall and four feet wide, giving it a somewhat squat appearance when left untrimmed.

However, it can be shaped with light trimming during the winter period when it is dormant.

One specific cultivar, ‘Suffruticosa,’ or English boxwood as it is commonly known, was first grown in the United States in the 1700s.

It can reach a mature height of three feet and grows so slowly that it rarely requires pruning, only putting on about an inch of growth each year.

With a cloud-like habit, this type is hardy in Zones 5 to 8.

Dwarf English boxwood plants in #1 containers are available from Nature Hills Nursery.

‘Calgary’ is another nice option with a compact habit. And it can withstand freezing temperatures as well as summertime heat and humidity, in Zones 3 to 9.

Find plants in #3 containers at Nature Hills Nursery.

Littleleaf

With a smaller overall stature as well as smaller leaves than the common species, you’ll see a few variants of this type, and breeders may choose to write these on plant labels in a variety of ways.

B. microphylla var. koreana, aka Korean boxwood, is a littleleaf variety that is suited to Zones 4 to 9, making it a good option for northern growers.

It has a dense form and reaches around two to three feet tall and four to six feet wide at maturity, with yellowish-green foliage.

Not sure which cultivated type to choose? Look no further than ‘Wintergreen.’

This dwarf cultivar is incredibly versatile: It can be sheared into precise shapes, it’s a popular choice for foundations and formal gardens.

You can find ‘Wintergreen’ plants in quart-sized, one-, three-, and seven-gallon containers available from Fast Growing Trees.

A close relative of the Korean variety (and a member of the same species), Japanese boxwood is another popular type.

There are a few different cultivars of B. microphylla var. japonica available to home gardeners, but ‘Winter Gem’ is one of the most popular.

It serves as a smaller alternative to English boxwood and grows in a compact fashion, usually only reaching two to three feet tall at maturity.

Hardy in Zones 5 to 9, this variety has deep green foliage, and it can tolerate heavy pruning.

You can find plants available in #1 and #3 containers from Nature Hills Nursery.

Managing Pests and Disease

Boxwood is an easy plant to grow, with very few pests or disease issues to worry about. Most can be prevented with basic care.

Insects

There are several insect pests that are known to plague boxwood shrubs, many of which are exclusive to this kind of plant alone.

Leafminers

The boxwood leafminer (Monarthropalpus flavus) is the most dangerous pest that may threaten the health of this plant. It can cause serious damage, leading to blistered, discolored foliage.

Technically a small fly, this pest can be controlled by planting resistant varieties, including most Japanese types, or using an insecticide.

Read more about about controlling leafminers here.

Mites

Eurytetranychus buxi is technically a spider mite. It feeds on the underside of leaves and causes yellow and white spots.

It usually attacks B. sempervirens, with littleleaf types generally being less susceptible. Be careful about using too much high-nitrogen fertilizer, as this can increase the frequency of mite infestations.

If they do appear, get rid of them with a harsh blast from the hose or use horticultural oil.

Psyllids

Cacopsylla buxi, sometimes referred to as Psylla buxi, is less serious than the two aforementioned insects, but it can cause cosmetic damage to your plant – like poor twig growth and leaf cupping.

It tends to attack American boxwoods most often, wreaking havoc in the spring after overwintering in the soil earlier in the year. You will need to use insecticides to get rid of it.

Mealybugs

Mealybugs, a number of species in the Pseudococcidae family, are challenging to control with insecticides, but you can get rid of them with insecticidal soap, or a forceful blast from the hose.

Not only can they weaken your boxwood plants by draining them of their energy reserves as they eat, mealybugs also excrete honeydew, a substance that attracts ants, and can lead to sooty mold.

Learn more about controlling mealybugs here.

Parasitic Nematodes

There are several kinds of nematodes that will go after boxwood plants, and these pests can cause stunted growth.

To prevent them from impacting the health of your plants, grow resistant varieties like B. sempervirens and be consistent with care by watering, mulching, and fertilizing on a regular basis.

Scale

Various species of scale, a sucking insect in the Coccoidea family, that can cause unattractive leaf scarring may infest your boxwood shrubs.

The pests look like tiny white bumps, and when you remove them from your plants, you’ll notice green scars that cannot be removed in their place.

Fortunately, this pest doesn’t usually kill plants or cause long term effects beyond surface-level cosmetic damage. If your plants suffer from an infestation, you can prune away areas that have been affected.

Find more information on controlling scale insects here.

Disease

Most diseases of plants in the Buxus genus can also be prevented and addressed by following good watering and garden hygiene practices.

Here are some of the most common culprits:

Blight

Boxwood blight is caused by the fungal pathogens Neonectria pseudonaviculatum and Cylindrocladium pseudonavitulatum.

The fungi cause the leaves on the lower part of the shrub to develop brown spots and twigs to form lesions.

Blight can kill young plants, with littleleaf boxwoods being the most susceptible.

You can limit the spread of this disease by cleaning all of your gardening tools thoroughly and destroying affected plant parts.

Make sure your plants are thinned and spaced properly for good airflow, and use a fungicide when necessary.

Leaf Burn

Leaf burn causes the leaves of your boxwood to turn red or yellow and fall prematurely. This physiological disorder is caused by water stress and low temperatures.

Plant your shrubs in an area that is protected from wind and make sure they are watered well during dry spells.

Leaf Spot

Leaf spot causes leaves to turn yellow and become speckled with black.

A fungal disease caused by Macrophoma candollei, it can be prevented by protecting your plants from wind and salt spray.

Boxwood Best Uses

While you might use a boxwood shrub as a specimen plant, it’s best used when grouped together in a foundation planting or in a hedge.

You might even consider using them as topiary, bonsai, or knot-garden plants.

You can even cut your boxwood for use in holiday arrangements like wreaths, kissing balls, garlands, and more.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Woody shrub | Foliage Color: | Green, yellow-green |

| Native to: | Asia, Europe | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 4-9 | Soil Type: | Average to organically rich |

| Season: | Spring, summer | Soil pH: | 6.5-7.5 |

| Exposure: | Full sun to partial shade | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 2-3 feet (less for a hedge) | Attracts: | Bees, birds |

| Growth Rate: | 12 inches per year | Companion Planting: | Hosta, rosemary, thyme |

| Height: | 5-15 feet | Uses: | Foundation plantings, hedges, topiaries, cut holiday arrangements |

| Spread: | 5-15 feet | Order: | Buxales |

| Tolerance: | Slightly acidic soil, shade | Family: | Buxaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Buxus |

| Pests & Diseases: | Boxwood leafminer, mite, psyllid, mealybugs, parasitic nematodes, scale; blight, leaf burn, leaf spot | Species: | microphylla, sempervirens |

Hedge Your Bets with Boxwood

If you’re looking for an ornamental shrub that can be grown as a small tree, a border, or yes – to form a hedge! – consider growing boxwood.

This plant is hardy, easy to grow, and provides garden interest in all seasons.

Have you ever grown boxwood shrubs before? Do you grow them as hedges, topiaries, or in some other fashion? Let us know in the comments section below, and feel free to ask any questions you have about growing these elegant shrubs.

A good gardener never stops learning – you’ve got to keep working on that green thumb!

If you want to read more about growing ornamental shrubs in the garden, take a peek at these helpful guides next:

Thank you for such an informative article, it will help me on my Bonsai Journey!

I bought 20 plants Japanese boxwood shrubs from Lowes and planted around my patio. Out of 20 plants 2 plants dying and become dry leaves and yellow. All others are healthy and green.

Please recommend to me what to do to keep them alive.

Thanks

Hello Ghulam Siddiqu I am sorry to hear about those two boxwood, and I am glad the other 18 don’t have an issue yet. From your description of the symptoms, I think the two diseased shrubs might have boxwood blight, which is caused by certain fungi and attacks young shrubs in particular. You should go ahead and uproot the plants that are doing poorly and destroy them so the blight doesn’t spread. I’m not sure if you planted the new shrubs at least two feet apart, or at least a foot apart if you intend to grow them as a… Read more »

A landscaper is proposing green mountain boxwoods 18-24″ – is that the height of the plant from where the plant touches the ground up to the top of the plant? or could that be the circumference of the plant?

I’d be surprised if a landscaper used a measurement like that to refer to circumference. That seems more like the it’s describing the starting height of your green mountain boxwoods.