Coffea arabica

Whether you’re a confirmed java lover or more of a tea person, coffee plants are excellent to have around.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

They have big, beautiful, glossy leaves and are pretty darn forgiving of those with black thumbs. If you forget to water your plants or live in a dry climate though, take note:

These plants will be grumpy with you, unless you keep on top of giving them what they want.

Think of a coffee plant as a very undemanding pet. Whether you have lofty goals of raising them to produce some of your own beans or if you just want to enjoy their outstanding foliage, this guide will get you there.

Here’s everything we’re going to discuss to make it happen:

What You’ll Learn

Grab a cup of joe and settle down with your laptop or mobile device. Let’s discuss how to make this lovely bush thrive.

What Is a Coffee Plant?

This isn’t one of those confusing naming situations where we call a plant something that it in fact isn’t.

Though a Douglas fir isn’t a fir and asparagus ferns aren’t true ferns, coffee plants are the same plants that give us that energizing morning cuppa, species from the Coffea genus.

Indoors, Coffea specimens can grow up to six feet tall in the right conditions, but most of them stay much smaller when grown as houseplants.

You could also grow them in a greenhouse, or outdoors if you live in USDA Hardiness Zone 10 or 11. In Zones 8 and 9, you can also grow them outside if you can provide protection from freezing weather.

Although the beans, as we know, are edible, the rest of the plant is toxic to humans and pets – so don’t go looking for your caffeine fix by nibbling on the leaves.

C. arabica is grown commercially for its seeds, aka the “beans.”

As the flowers die and fall away, a tube known as the carpel is left behind. This carpel matures over months into a cherry, which holds the seeds inside.

The seeds are roasted and then ground, and turned into that brew that so many people crave.

As houseplants, it’s rare for them to produce delicate white flowers, followed by clusters of red berries, but it’s not impossible.

If they’re positioned in the right amount of light and receive the right care, you may be rewarded with pretty flowers.

There are dozens of Coffea species, but it’s arabica that you’ll most often come across.

C. canephora, aka “robusta,” is another popular variety for commercial cultivation to make caffeinated beverages.

Cultivation and History

The history of when coffee was first discovered and cultivated has been lost to time.

The genus was probably first discovered in the region of modern Ethiopia before word spread and people began cultivating and trading beans on the Arabian Peninsula.

We know for certain that coffee was being cultivated in the 1400s in what is now Yemen, and it had spread to the modern region of Egypt, Syria, and Turkey by the 1500s.

Public coffeehouses started appearing in cities and European travelers brought the delicious stuff back to their homes during the 1600s.

As with many plants and foodstuffs carried from the East to the West, the brew created from the once-mysterious beans was first considered an evil drink, but eventually gained wide acceptance.

As a houseplant, it’s not clear how long people have been keeping this tolerant little beauty in their homes, but it has become more popular in recent years.

Propagation

All of the following methods can be done at any time of year, but spring is best.

From Seed

You can’t grow a plant from a coffee bean in a bag purchased from the store.

They’ve been roasted and won’t germinate. And don’t use green beans meant for roasting – those won’t germinate either.

Fresh coffee cherries or seeds intended for planting are pretty uncommon in nurseries, but the good old internet can always help.

For example, you can find a packet, ounce, or quarter-pound of seeds available at Eden Brothers.

Once you’ve gotten your hands on some seeds, fill a six-inch pot with an appropriate potting medium as described in the How to Grow section below.

Plop two seeds into the pot and push them in about a quarter-inch deep using your finger. Water the potting medium but not to the point where it feels soggy.

Tent a plastic bag over the container or cover it with a glass cloche. You can also cut the top off of a clear plastic two-liter soda bottle to make a little DIY cloche.

We’re trying to increase the humidity here, because most homes are lower in humidity than what these plants prefer.

Place the container in a spot with bright, indirect light.

Check the soil every day to make sure it feels moist, and add water when necessary.

There will come a point in about a month or six weeks when you’ll start to wonder if your seeds are duds.

I like to think that the seed senses my fear and decides to hurry up and germinate at this point, because every time I’ve started to despair, a week or two later a green head pokes itself out of the medium.

Do I tend to anthropomorphize a lot? You betcha!

If both of your seeds germinate, just pluck out and dispose of the smaller one. Once the seedling is a few inches tall, you can move it to its new home as described in the transplanting section below.

We have more tips for growing from seed here.

From Cuttings

Coffee plants are fairly reliable when you propagate them this way, if you have access to a mature specimen, but you really need to keep on top of the humidity situation.

If the cuttings don’t stay quite humid enough, they tend to fail.

To get started, fill a six-inch container with your choice of packaged seed-starting medium.

Take a six-inch-long cutting from a healthy specimen and remove all but the top two leaves. Stick the cutting into the soil about an inch deep.

Water the soil well so it feels moist but not wet and then, just as we do with the seeds, cover it with a plastic bag, cloche, or bottle to increase the humidity around the cutting.

Once every day, check the soil to make sure it’s moist, and go ahead and spritz the foliage with a water bottle if you want to, to increase humidity – though I’ll offer more information on the best ways to do this below, so don’t miss that!

Just as we had to practice patience with the seeds, we need to be patient while we wait for cuttings to form new roots.

Coffee may give us lots of energy to zip around and get things done quickly, but the plants themselves take their sweet time.

After about four weeks, give the cutting a gentle tug. If it resists, your cutting has roots and you can transplant your new C. arabica. If not, keep at it.

If roots haven’t formed by the eight-week mark, your cutting didn’t take. Try again.

Transplanting Seedlings

If you’re not feeling the whole cutting or seed propagation thing, no problem.

You can find seedlings in stores pretty easily. You might find them being sold as houseplants or as outdoor plants, but they’re both the same.

Once you bring your new beauty home, remove it from the nursery pot.

This might seem like an unnecessary step when you can just set the plastic container inside a decorative cachepot and call it a day, but we want to check out those roots.

Brush away as much of the dirt as you can from the roots and then rinse them off in warm water. Examine the roots for any black or mushy bits and remove those.

Fill a new container that is just slightly larger than the root ball with a bit of water-retentive potting soil and place the root ball inside. Fill in around it with fresh soil.

You want the plant to be sitting at the same height it was in the nursery pot.

The container material doesn’t matter, just make sure that it has good drainage.

When it comes to selecting soil, any potting mix with water-retentive elements such as vermiculite, sphagnum moss, or coco coir should do nicely. You can add rice hulls for a little boost of extra drainage and water retention.

While coffee plants prefer an acidic pH between 4.9 and 5.6, if you aren’t concerned about your plants producing flowers or seeds and you’re just in it for the foliage, a neutral pH (7.0) is fine.

How to Grow

Water, water, water. That’s the key to keeping your coffee plant happy. We want water in the soil, and water in the air.

You can use a soil moisture meter or just your handy dandy finger, but either way, check the potting medium every few days.

You know when you wring out a sponge really well? That’s what you want the soil to feel like at all times.

You have to be careful, though. Sometimes the top inch or so feels just right, but near the bottom of the pot, the soil is soggy and wet.

Don’t get too comfortable and start to assume you don’t need to feel the soil regularly.

Your specimen will likely require less water to maintain the right level of moisture in the winter, so seasonal adjustments are a must, with the surrounding indoor environment in mind.

Coffee plants also love humidity. These are not happy campers in dry air and the edges of the leaves will quickly turn brown and crispy if they’re left in dry conditions.

They also stop sending out new leaves, or young leaves might die, when humidity is low.

I don’t find misting to be particularly helpful in preventing the leaves from turning brown, so use a humidifier, cluster plants together on a humidity tray, or grow them in pretty cloches.

You want the humidity around the plant to be 50 percent or higher.

When it comes to picking a potting mix, there isn’t much to it. C. arabica will be perfectly fine in any of the many generic houseplant mixes available at the store.

I’m a huge fan of FoxFarm Ocean Forest potting mix, which is available from Amazon in 12-quart bags.

I have yet to find a plant that doesn’t thrive better in this mix over other generic mixes. It has a healthy balance of nutrient and water retentive properties while still draining well.

Keep the plant somewhere that has bright but not direct light.

A place in front of a window with a sheer curtain would be great. Or keep them in a north-facing window, or a few feet away from a west-, east-, or south-facing window.

Once every month, feed with a balanced liquid houseplant fertilizer.

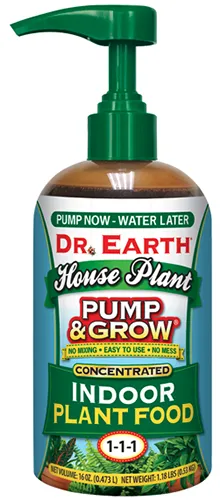

I like to use Dr. Earth’s Pump & Grow, which is mild enough that it won’t burn roots and well-balanced for use on most houseplants.

Arbico Organics carries this fertilizer with a handy pump top in 16-ounce containers.

Growing Tips

- Provide bright, indirect light.

- Keep the soil moist.

- Humidity is key for healthy plants.

Pruning and Maintenance

Coffee plants tend to get leggy as they age. And the lower part will start to become bare, with all the foliage concentrated at the top.

Your best defense against naked legs and legginess is to prune regularly.

As soon as your specimen reaches a size you like, trim it back by about a quarter or so. Make your cuts just above a leaf node to encourage new, bushy growth.

These plants will send up new stems at the base, which can help hide that leggy growth.

Don’t forget to dust the leaves now and then with a damp cloth.

Growing Beans

Most of the time, your coffee plant won’t flower or produce fruit. You didn’t do anything wrong, it’s just difficult to maintain the right conditions for it to fully flourish indoors.

But if you really like the idea of encouraging your plant to flower and fruit, you can give your coffee a helping hand.

First, it should be placed outside during the summer to more closely replicate its natural habitat, and improve pollination when in flower.

Bring pots outside when nighttime temperatures are consistently over 50°F.

You’ll also want to increase the soil acidity by amending with sulfur or aluminum sulfate.

Grab a pound of pure, food-grade aluminum sulfate from Pure Original at Amazon.

Mix a quarter-cup with a gallon of water and water the surface of the soil. If you don’t use it all up in one go, you can save the solution for up to a month to use for the next watering session.

Wait a day after watering and test the soil pH.

If it still isn’t low enough, within the range of 4.9 to 5.6, wait two weeks and water with the aluminum sulfate solution again. You can do this two or three times as needed, to amend the potting medium.

Keep your plant in dappled shade and ensure the soil remains moist. The soil will dry out more quickly outside, so be diligent about checking the moisture level and watering.

While these plants are self-fruitful, it also helps to have a second one to boost pollination.

When you bring your plant back inside in the fall, when evening temperatures are dipping right around 50°F again, reduce the amount of water you provide.

The soil should be allowed to dry out just a bit more than usual, allowing the top inch to dry between watering.

By the second summer, if the stars have aligned and you did everything right, you should at the very least see a few beautiful white flowers, which look and smell a bit like jasmine.

The fruit will follow, if the flowers have been pollinated successfully and conditions are right.

Cultivars to Select

There are dozens of coffee cultivars out there. But most houseplants are simply sold under the species name, and these are usually C. arabica, as we’ve covered here.

Fast Growing Trees has potted specimens available in gallon- or three-gallon containers, as well as one- to two-foot and two- to three-foot options.

Cultivars have mostly been bred to improve the quality of the beans, not for their value as houseplants, so you won’t find named varieties with variegated leaves or extra-full flowers, for example.

Having said that, you can occasionally find variegated specimens available from rare plant sellers. If you’re growing one, send us pictures!

The following recommended cultivars are particularly suited to growing indoors because they have compact, bushy growth habits and particularly attractive foliage.

Bourbon

‘Bourbon’ is an extremely common cultivar and one that has been used to create countless newer cultivars. It was bred from wild types of coffee growing in Yemen.

A few dozen trees were obtained by French growers, likely missionaries, in the early 1700s and planted on what is now known as Reunion Island, off the coast of Madagascar.

Eventually brought to Brazil in the mid-19th century, this cultivar spread from there through the Americas and East Africa.

This C. arabica cultivar has a round growth habit with broad, round leaves and spherical fruit.

Gesha

‘Gesha’ – not “geisha” – is a cultivar bred via natural mutation from a ‘Bourbon’ plant. It’s named after the town in which it originated in Ethiopia.

While it’s a favorite in commercial coffee production because of its rich flavor, it’s also quite pretty. It has a bit more weeping, bushy growth habit than its parent.

As a houseplant, you won’t notice this shape until it has matured a bit.

Typica

‘Typica’ is one of the oldest arabica cultivars and, along with ‘Bourbon,’ is one of the two parent plants used commonly to create dozens of newer cultivars.

It was first bred in Yemen before traveling to Ethiopia, India, and eventually to Europe and the Caribbean, carried by Dutch travelers.

This was the only coffee plant you could find in the Americas until the middle of the 19th century.

It has a conical growth habit and the leaves are more narrow than those of many other cultivars. The berries are also narrow.

Managing Pests and Disease

As long as you keep your houseplants healthy, I find pests and pathogens will go for other species before they’ll attack Coffea plants.

No doubt that’s in part because caffeine is a natural insecticide, much like the glucosinolate that mustards produce.

The biggest risk your plants may face is going to be root rot. They love moisture, but too much will drown them.

Insects

Coffee plant houseplants are “bugged” by what I think of as the big three: aphids, mealybugs, and spider mites. If you’re growing indoor plants, you’ll probably see one or all of these at some point.

Aphids

Aphids are tiny insects that use their sucking mouthparts to draw the sap out of plants. For pretty much every plant species, there are one or more aphid species that may potentially feed on it.

Outdoor coffee plants are attacked by different aphid species than houseplants, which are commonly visited by the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae.

But it doesn’t really matter which species is visiting – you can treat them all the same.

The damage is evidenced by yellowing and browning leaves. Look closely and you’ll likely see clusters of light green bugs on the undersides of the foliage.

You might also see a sticky substance called honeydew, which can attract sooty mold.

Isolate the infested coffee plant while you treat it. This will take a few weeks.

Set the plant in your shower or bathtub and spray it with water. You might need to cover the soil with plastic so you don’t overwater it.

Let it dry and then treat it with neem oil, saturating the leaves, both top and bottom, the stems, and the soil.

Do this once a week until you don’t see any more aphids.

For more tips, read our guide to managing aphid infestations.

Mealybugs

Mealybugs can look a lot more like a sign of disease than a pest.

These bugs are covered in a waxy white coating and they move really, really slowly – so they can look a bit like a fungus. They like to chill together on the undersides of leaves and near stems.

Like aphids, they make a meal by sucking the juice out of the plants. They also leave similar evidence of their presence behind, including yellowing and brown leaves, and excreted honeydew.

If your coffee plant is small, the easiest way to deal with them is to dip a cotton swab in isopropyl alcohol and wipe each insect. This removes their protective coating and kills them.

You can also just handpick them off.

For large specimens, you might want to turn to insecticidal soap or horticultural oil. Check out our guide to learn more about how to treat mealybugs.

Spider Mites

Spider mites are tiny arachnids in the Tetranychidae family. They’re pretty small, so don’t bother trying to identify them by their appearance. Look for the fine webbing they leave behind instead.

These webs will often be filled with tiny dots, which are the discarded skins of the mites.

When they feed on your plants, this results in wilting and blotchy yellow spots on the foliage.

It’s pretty easy to treat spider mites. They thrive in dry conditions, so up that humidity! Remember, that’s an essential part of keeping coffee plants happy.

To knock the pests off the plant, spray it with water. Do this once a week and you should be rid of them in no time.

Disease

Plants grown indoors are less likely to be contaminated by some of those awful bacterial and fungal diseases that travel far and wide in the great outdoors.

But if you take your coffee plants outside during the summer, or if you use your outdoor tools on your houseplants without sanitizing them first, you might transmit something infectious.

Always be sure to clean your tools, whether they’re exclusively used on your houseplants or not!

Here are the most common ailments you may come across:

Collar Rot

Unfortunately, the oomycete that causes collar rot, Rhizocotonia solani, is everywhere.

In young coffee plants, like the ones you might buy at the nursery, it shows up as a brown, sunken area on the stem near the soil. If you see this, don’t buy the plant.

If symptoms show up later, drench the soil with copper to try and kill the pathogen.

Many times, stems that are already symptomatic will die despite your best efforts. But the plant will send up new, healthy stems when it recovers.

Bonide Liquid Copper Fungicide

To drench the soil, grab a liquid copper fungicide concentrate. Arbico Organics carries Bonide brand, which I love.

Mix a teaspoon of it with a cup of water. Pour the water evenly over the potting soil. Repeat every 10 days for up to two months.

Root Rot

Root rot can be a fungal issue or a physical one. Either way, it’s caused by overwatering.

When you overwater, it drowns the roots and also invites pathogens like Armillaria mellea and Fusarium solani, which cause the roots to turn mushy and black.

Indoors, A. mellea is rare – I’ve never heard of it causing an infection in a houseplant regardless of the plant species, though I suppose this is theoretically possible.

Of course, you probably aren’t examining your plant’s roots on a daily basis, so how on earth would you know the roots are quietly rotting underground? Droopy foliage is the tell-tale sign, and black or brown areas will appear on the leaves and gradually expand.

Low humidity can also cause brown areas to develop on foliage, but you can tell the difference here because root rot spots are darker brown and they usually start on the inner parts of the leaves.

The foliage might also turn yellow, but it will be soft and moist rather than dry and crispy.

Because it’s hard to tell without a test whether drowning roots or a pathogen is causing this problem, you need to treat for both.

First, water less often and make sure that the pot is still draining freely. Those drainage holes can become clogged over time.

Also, be sure to drain any catchment container used beneath the pot within half an hour of watering.

Then, drench the soil with copper as described above for collar rot.

Find tips on dealing with root rot here.

Best Uses

While a single coffee plant looks absolutely lovely on its own, as it ages, I like to grow something at the base in the same pot. Pothos, string of hearts, and philodendron all look nice.

It’s also a fun challenge to try to grow some flowers and fruits. Who knows – maybe someday you’ll have a few of your own beans to roast and brew!

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Woody shrub | Foliage Color: | White (red berries)/green, green and white |

| Native to: | Arabian Peninsula, Ethiopia | Tolerance: | High humidity, heat |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 10-11 | Soil Type: | Rich, loamy potting soil |

| Exposure: | Bright, indirect light | Soil pH: | 4.9-5.6 |

| Planting Depth: | 1/4 inch (seeds); same depth as nursery pot (transplants) | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Height: | Up to 15 feet | Uses: | Houseplant, ornamental, edible seeds |

| Spread: | Up to 10 feet | Order: | Gentianales |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate | Family: | Rubiaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Coffea |

| Common Pests and Disease: | Aphids, mealybugs, spider mites; crown rot, root rot | Species: | Arabica |

Enjoy Your Morning Coffee in Plant Form

As long as you give them the moisture they crave, coffee plants aren’t too challenging to grow.

Plus, they add such a beautiful, tropical element to your home. You might even be lucky enough to enjoy the intoxicating blossoms.

If you are able to coax your coffee plant to produce flowers or fruits, let us know how you found success. Better yet, share some pictures with us in the comments below!

Want to grow a few other multi-purpose houseplants? Here are some fun options:

My coffee plant is now 20 yrs old and has produced many pounds of coffee beans. I’ve planted many of its seeds and started many new coffee plants as well. I recently learned that I should “stump” (prune) the plant to about 50-60 cm from the ground to promote more beans, as it’s almost stopped producing in the past year or so. Wish me luck! Ha!!

Hi Marten, that’s incredible! Thanks for the tip, enjoy those beans!

I inherited a coffee plant a few years ago, and it’s getting out of hand! I don’t think it’s ever been properly pruned. How much off the top would you recommend I chop to keep the height down? If I take enough off, will more branches start sprouting from lower down the stem, or has that ship sailed? LOL