I love garlic! On toast, roasted and drizzled in olive oil, whole cloves on my pizza, diced pieces in my guacamole… It doesn’t matter how I use them, I love it all.

And I also love how garlic repels many of the pests that try to feed on my favorite veggies. What’s not to like?

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

But at the same time, I hate garlic.

It seems like every year, something infects my plants. Sometimes it’s a touch of rust, and other years, it’s devastating rot.

I’ve gotten pretty good at preventing most diseases, so I rarely lose a bulb anymore. But it requires constant vigilance.

Whether this is your first year experiencing problems or you’ve been struggling with something every year, we’ll help you through it.

Here are the diseases we’re going to cover:

7 Common Garlic Diseases

I don’t mean to make it sound like you will always face disease issues.

Once you know what conditions they thrive in and the tricks for avoiding them, garlic disease could mostly be a thing of the past in your garden.

Let’s get one of the worst issues out of the way first…

1. Basal Rot

Basal rot is nasty business. It’s the most serious threat to commercial garlic production in the world.

This is a disease caused by a fungus called Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cepae. If it infects your garlic plants, it can cause yellowing foliage and dying leaves as well as rot below ground.

The tips of the leaves will turn yellow first, and then the disease will work its way down the rest of the leaf to the base.

That’s because the rot prevents water from moving from the roots to the foliage, so the parts that are furthest away die off first.

You know that hard, flat bit at the bottom of each clove that you usually cut off when chopping them up in the kitchen?

That’s part of the basal plate, the area on the plant where the cloves emerge from growing upwards, and the roots emerge from growing downwards.

This is the part of the garlic plant that suffers first when basal rot is present.

As it progresses, it turns the roots pink to black and may even move into the base of the cloves in the form of white or pink fungal spores.

What makes it worse is that it can continue to spread even after you harvest and store your garlic bulbs, which means they might look okay when you harvest them, but they eventually rot away while they’re waiting to be cooked.

The pathogen lives in the soil, and it can survive for decades even if a host isn’t present. I told you this was nasty stuff.

While the fungus can infect any allium, plants that are damaged either by insects or accidents while planting or weeding are more prone to infection.

It’s only active when temperatures are between about 59 and 90°F, so you don’t have to worry about it during the winter. But when the growing season starts, look out!

While the pathogen can survive in the soil, it will reduce in numbers over time if a host isn’t present. For that reason, it’s best to rotate your alliums out every three years.

In the meantime, don’t plant corn, tomatoes, sunflowers, black beans, cowpeas, or oats. These plants can act as alternate hosts.

If you find signs of this disease in your garden, store the harvested bulbs at 33 to 39°F to prevent it from spreading further.

When you’re out shopping, look for garlic cultivars that are advertised as resistant to fusarium or basal rot.

2. Botrytis Rot

As with most diseases on this list, botrytis rot can infect any type of allium, but only Botrytis porri in particular will infect garlic.

Generally, you won’t have a clue that anything is wrong until you harvest the garlic bulbs and discover dark brown or black fungal spores and soft spots on the bulbs or the neck of the plant.

If an infection is bad, you might see the outer leaves of the plant turn yellow and die.

Once you harvest, the disease can continue to develop and spread on the bulbs, so eat them right away without curing or store them immediately at temperatures below 41°F to stop the pathogen from spreading.

To prevent botrytis rot, avoid damaging the bulbs as they are growing in the garden since this creates wounds for the disease to enter through.

You should also avoid over-fertilizing and allow the bulbs to dry out a few weeks before harvest, if the cultivar that you’ve planted can tolerate that kind of treatment.

If you suspect this disease is present, you can treat the bulbs two months before and again a month before the expected harvest date.

A copper fungicide can be effective, but this might be the time to break out the big guns.

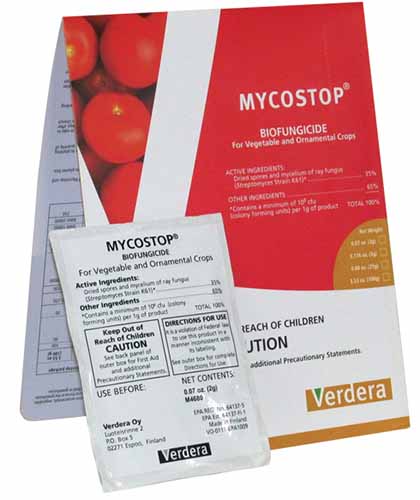

Something that contains the beneficial bacteria Bacillus subtilis or a product like Mycostop, which contains a bacteria derived from peat moss known as Streptomyces strain K61, are both more effective.

I’m always singing the praises of Mycostop because it works so well.

It has saved many of my plants from a range of fungal problems, including botrytis. If you want to try it out, grab a five- or 25-gram packet from Arbico Organics.

3. Downy Mildew

You might be familiar with downy mildew on other plants, like roses and cucurbits. This disease can strike alliums like garlic, too.

In garlic, it’s caused by the oomycete Peronospora destructor. A pretty sinister name, right? Destructor is Latin for destroyer, and that’s what this pathogen does: destroys your crop.

If you have a patch of garlic, you might notice a circular group of plants turning yellow before it spreads to nearby plants.

If you grow your garlic in rows, it might just be two or three plants next to each other that are showing symptoms.

Either way, you’ll see leaves that first turn a bit pale before turning yellow or brown. Left untreated, they will turn completely brown and die. In humid climates, you’ll even see white fuzz on the foliage.

Don’t assume the garlic bulb is safe from this disease just because it’s hiding below ground. It’s slowly rotting, turning watery and soggy.

The oomycetes need moisture and cool temperatures to reproduce and spread. That’s why you usually see downy mildew in spring or fall, or in winter in areas with temperate climates.

The most damage occurs when temperatures are between 43 and 61°F. Above 68°F the spread slows dramatically or even stops.

Since moisture is a crucial element in the success of these pathogens, you need to do what you can to control it.

As we can’t change the relative humidity, we need to do things like plant with adequate spacing instead. You should also water at the soil level and avoid sprinkler irrigation.

Rotate alliums out for three years after planting, and destroy any infected plants if you opt to pull them rather than treating the plants. Don’t put them in the compost.

Mancozeb or a product containing Streptomyces lydicus strain WYEC 108 are both effective at treating the disease, provided you catch it in the early stages.

Arbico Organics carries 18-ounce bags of Actinovate AG, which contains this powerful microbe.

Once the bulb starts to rot, there isn’t much you can do.

4. Mosaic Virus

Garlic mosaic virus (GarMV) and onion yellow dwarf virus (OYDV) are diseases carried by aphids. Many plants might be infected and won’t show any symptoms.

Other times, growth might be stunted, or you might see stripes, mottling, or mosaic patterns on the leaves.

The only way to prevent these viruses is to keep aphids away from your plants and to only purchase certified disease-free seed cloves.

Once a virus strikes, there isn’t anything you can do to cure it. It’s best to pull the infected garlic to prevent the disease from spreading to other plants, but you can leave them in place if you want.

If you aren’t certain whether a virus is infecting your plants, you can always send a sample to your local extension office. They can test the sample and let you know what you’re dealing with.

5. Purple Blotch

Are you picturing a disease that causes purple blotches on the leaves of your garlic plants? Nailed it! That’s what the fungus Alternaria porri causes.

It targets onions more often, but it will also infect garlic and leeks. This disease thrives in humid conditions when temperatures are between 75 and 85°F.

The pathogen favors older leaves, and purple blotches develop after the disease has progressed. Initially, you’ll see sunken, water-soaked spots that will turn brown with yellow halos before turning purple.

It can also infect the garlic bulbs underground, turning them reddish-purple before they rot completely.

Because the pathogen needs water to reproduce, increasing air circulation will help limit it.

That means providing appropriate spacing, watering at the soil level, and watering in the morning so any drops that spray the plants evaporate quickly.

You should also practice crop rotation. Only plant alliums in the same spot once every four years.

If you spot symptoms, immediately start treating the plant with copper fungicide, both as a foliar spray and a soil drench.

Keep doing this every three weeks until no new symptoms develop and no existing symptoms worsen.

You can pick up a 32-ounce ready-to-use spray or a 16-ounce copper fungicide concentrate at Arbico Organics.

6. Rust

I’m always looking for the bright side of things, and when it comes to rust, the bright side is that this disease is pretty easy to diagnose, and it usually won’t kill a plant.

The fungus that causes it, Puccinia porri, shows up as raised, reddish-orange, oval-shaped or circular pustules. As the disease goes on, the pustules darken, and the leaves might turn yellow.

P. porri needs high humidity and temperatures between 55 and 75°F to reproduce, so you usually see rust in spring and fall. It can infect any allium, but it likes garlic best of all.

There are resistant (not immune) cultivars, including all elephant garlics. If you see signs of the disease, treat the leaves with copper fungicide every three weeks.

7. White Rot

I’m going to just lay it all out. This disease is bad. Really bad.

White rot hasn’t become a huge problem in all parts of North America… yet. It’s rapidly spreading and exists in all states, but it’s worse in some areas than others.

The fungus that causes the disease, Stromatina cepivorum, can live in the soil for decades, even if there are no alliums planted there for it to infect.

When soil temperatures are between 50 to 75°F, this disease can move throughout the soil, infecting any allium it finds in its path.

The fungal pathogen can spread in water, soil, on equipment, or on plant material. Once a plant is infected, there is no cure and the plant will eventually die.

When a garlic plant is infected, the bulb will rot away, with white and black fungal growth appearing on the base and up into the cloves.

It will spread into the leaves, causing them to turn yellow and die back. Once you see symptoms on the upper parts of the plant, there’s not much you can do but pull the plants and dispose of them.

Since you can’t get rid of this disease, you need to avoid it. The first step is to buy disease-free seed or to dip clove seeds in 115°F water – use a spoon, not your fingers – to kill the pathogen. Don’t go any hotter because it might kill the garlic.

Always take care to clean your tools between uses, and don’t bring any plants or soil to your garden from areas that you know have been contaminated.

If your garlic is infected despite your best efforts, you can eat any asymptomatic bulbs. Toss out anything that shows symptoms in a sealed garbage bag.

Don’t plant any alliums in the same area unless you replace the top six inches of soil or solarize the soil to kill the pathogens.

Kiss Nasty Pathogens Goodbye

If you do your best to reduce excessive moisture, take care to clean your tools, and practice good crop rotation, you’ll significantly reduce the chances of ever dealing with one of these issues again.

Were the symptoms you spotted on this list? Did we help you narrow down the possible causes? I hope so! Let us know what you’re experiencing and if you have any other questions about how to deal with it in the comments.

Now that you don’t have to worry about diseases anymore, you might want to learn a bit more about growing garlic. If so, here are a few guides to get you started:

Very nice and informative post! We have plenty of garlic fungus problems – mostly storage rot (botrytis?). How do you treat garlic with the Mycostop, with a clove dip at planting, or some other technique? Thanks

Hi Dick, thank you for the kind words. There are a couple of causes of storage rot, including botrytis and bacteria. It can be a pain.

I use Mycostop both as a soil drench and as a foliar spray, depending on the problem I’m addressing. For botrytis, I use it as a soil drench, following the manufacturer’s directions. I haven’t had to deal with storage rot in years. Best of luck to you!

I planted Inchelium Red last fall in central MA. All the plants are lying down & have NO ability to stand straight up. I have them planted near some Russian Red which are healthy & fine looking. What did I do wrong?

Hi Dave, as ‘Russian Red’ is a hardneck type and ‘Inchelium Red’ is a softneck type, they will have different needs and reactions to their environment. You might want to visit our guide to garlic leaves falling over to understand why this might be happening. It can be a number of different issues, from water or light issues to it being time to harvest.