From positives such as creation and passion to negatives like destruction and pain, the thought of fire conjures up many different things for different people.

Unfortunately for plants, the “fire” in “fireblight” is anything but awesome.

A truly gnarly disease, fireblight is all the more awful when you’re a grower of apples, pears, or plums – three rosaceous, fruit-bearing trees that fireblight can afflict with ease.

If an infection were to occur, you’d be left with sickly-looking plants and very inedible fruits.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

So how can a grower prevent this condition from striking their orchard? And how can one manage a bout of fireblight that has already infected and begun to damage their poor plants?

With the greatest tool in a gardener’s toolbox, that’s how. No, no, not your trusty hori-hori knife or Felco F-2s. I’m talking about knowledge.

This guide has everything you need to know about fireblight.

What it is, the disease’s symptoms and life cycle, the works. It also covers how to combat a current infection, and even how to keep infections from occurring in the first place.

To borrow from the legendary ring announcer Michael Buffer, let’s get ready to rumble.

What You’ll Learn

Fireblight 101

As Sun Tzu once said, “know thy enemy.” Feel free to consider the following info a part of your pre-battle briefing.

What Is Fireblight?

Fireblight is a very serious bacterial disease of over 130 species of trees and shrubs in the Rosaceae or rose family.

It’s a grim threat for home and commercial growers of susceptible fruit trees, as its introduction to a new place can significantly jeopardize that area’s fruit production and commerce.

The infection of trees such as apples, pears, plums, and other rosaceous plants grown for their fruits usually receive the most press, but even ornamentals from the Rosaceae family such as spireas, mountain ashes, and hawthorns are notoriously susceptible.

The causal pathogen is the bacterium Erwinia amylovora, a North American native that has since become a thorn in the sides of many apple, pear, and plum growers worldwide.

Fun fact about E. amylovora: it was actually the first bacterium to be proven a plant pathogen! But beyond that? There’s not much that’s fun about it.

As an epiphyte, it’s capable of growing and multiplying on plant surfaces before infections even take place, and it doesn’t even have to be on a susceptible plant to duplicate itself.

This multiplication can occur very quickly: in temperatures of 65 to 75°F, a population of E. amylovora can double itself every half hour!

Disease Cycle

Once the weather in springtime becomes sufficiently warm and wet, E. amylovora bacteria that overwintered in mummified fruits and certain large cankers of infected trees – often called “holdover cankers” – become active and begin to multiply.

The pathogen then releases fresh bacteria onto the bark’s surface, sometimes via the nasty-looking “ooze” that fireblight cankers exhibit.

The bacteria can then travel to new plants by hitching a ride on splashed water from irrigation or rainfall, a gardener’s hands or tools, beneficial insect pollinators, and even bugs such as flies that are attracted to the cankerous ooze.

Once they reach a plant, the bacteria will live and multiply on the surfaces of leaves, bark, flowers, and immature fruits.

Upon finding natural openings such as fresh wounds or opened blooms, the bacteria will enter the plant and travel along the vascular systems of branches to infect healthy wood, forming fresh new cankers along the way.

If the tree is young, unhealthy, and/or growing quickly, then the pathogen’s spread is all the swifter.

Eventually, the bacteria can reach the trunk and roots, which is usually the point when the infected plant is done for.

However, disease progression requires the growth period of spring and summer.

As the growing season comes to a close, terminal buds set, and new growth hardens, the pathogen ceases its spread, both within and between plants.

Once fall and winter roll around, mummified fruits and cankers become overwintering sites for the bacteria, where it will lie dormant until next spring.

It’s the circle of life… at least for E. amylovora. For the infected plant, it’s more like the circle of death, as it’ll harbor the pathogen indefinitely.

Symptoms

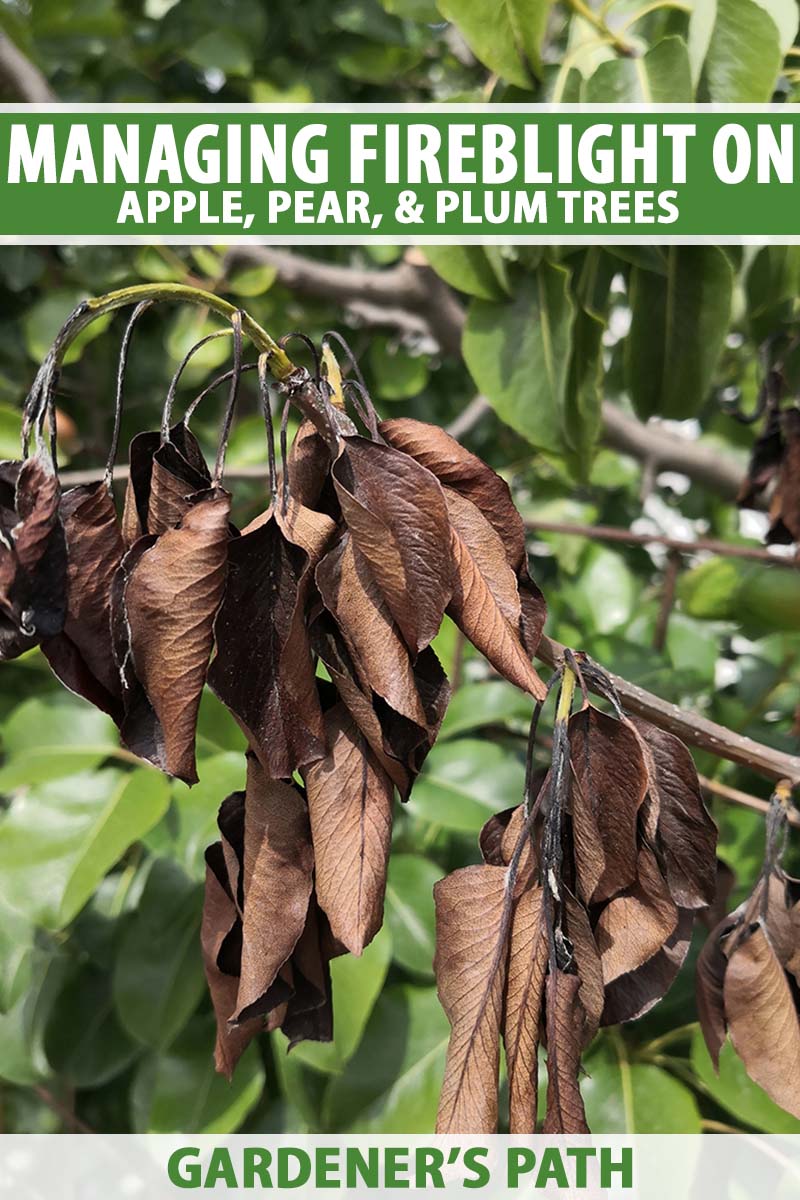

As you can tell from the grisly photos we’ve peppered throughout this guide thus far, fireblight doesn’t exactly leave its hosts in the best shape.

Let’s start with the foliage. After wilting and losing their lush greenness, they shrivel, turn brown or blacken, and hang downward, with the entire leaf stem drooping in an inverted J-hook shape, kinda like a shepherd’s crook.

Diseased flowers have a water-soaked look to them before developing similar symptoms to those of infected leaves, while infected fruits will darken and shrivel into a “mummy,” i.e. a withered husk.

These mummies can cling to the plant for months on end, which is more than enough time for E. amylovora to overwinter within.

Once bark becomes infected, cankers can form and the wood will begin to die back. It’ll become sunken, dark, and may even begin to crack or peel.

If you were to peel the bark back intentionally, you’d find the inner sapwood to be stained.

It’ll be brown and necrotic towards the infection site, reddish in the newly infected wood, and red-flecked in sections that the pathogen is just beginning to colonize.

But if you had to describe the symptoms in a one-sentence blurb for an easy diagnosis, I’d use this one: “Infected plant tissues will appear scorched, with darkened, shriveled foliage and fruits hanging limply from cankered, necrotic branches.”

The majority of this damage occurs in warm and wet conditions – think temperatures of at least 65°F and humidity of 60 percent or higher. This sort of environment allows the pathogen to reproduce and spread at peak efficiency.

All this damage causes plants a great deal of harm and can quickly lead to their demise.

Young and especially susceptible specimens can be killed in a single season, while more mature and durable trees can usually survive several years of branch dieback before perishing.

Either way, an infected specimen’s fruit production will be severely hindered.

Prevention Tips

I’m no Paul Hollywood, but I imagine that baking an apple pie, pear cobbler, or plum cake is tough when the key ingredients are mummified and full of bacteria.

Let’s discuss how to keep fireblight from infecting your fruit trees, shall we?

Plant Resistant Varieties

This tip comes with an asterisk: no variety of rosaceous plant is completely resistant to fireblight infection, if you were hoping for full immunity.

But by selecting varieties that are resistant enough to limit or slow disease progression, gardeners can buy themselves vital time for saving infected specimens.

Moderately-resistant apple varieties include ‘Empire,’ ‘Honeycrisp,’ ‘Liberty,’ ‘Stayman,’ and ‘Golden Delicious,’ and every strain of ‘Delicious’ apple possesses a high resistance.

Personally, I’m a sucker for ‘Honeycrisp,’ which can be purchased in three- to seven-foot sizes from FastGrowingTrees.com.

Growing pears? ‘Harrow Delight,’ ‘Kieffer,’ ‘Moonglow,’ ‘Magness,’ ‘Seckel,’ and ‘Starking Delicious’ are varieties with moderate amounts of resistance.

For a beautiful ‘Kieffer’ pear that’s offered at starting sizes of four to seven feet, visit FastGrowingTrees.com.

More of a plum person? Auburn University has developed some varieties for southern gardens that are resistant to bacterial diseases, such as ‘AU Cherry,’ ‘AU Rosa,’ and ‘AU Rubrum.’

But new cultivars are being developed all the time, so don’t let the above recommendations be the end-all-be-all.

Feel free to check with local orchards and extension agents, as they may have more specific recommendations for your area.

Monitor the Weather

Regularly checking the weather can help gardeners prepare for those warm and wet times when fireblight is especially likely to spread.

Additionally, destructive weather such as lightning, hail, and strong winds can damage plants, creating entry points that E. amylovora can use to gain access.

Keeping aware of upcoming thunderstorms, tornadoes, and the like will help gardeners in scheduling those prompt post-storm pruning sessions.

Avoid Excessive Nitrogen

Don’t forget that the more vigorous a plant’s growth, the faster the fireblight within can spread. And nothing turbo-boosts a plant’s growth rate quite like heavy nitrogen fertilization.

Avoiding this is as simple as not adding disproportionately large doses of nitrogen fertilizer during the growing season. Instead, keep any added N a moderate part of a healthy and balanced fertilizer program.

Prune Properly

The prompt pruning of dead or damaged plant tissues will help to shore up any vulnerabilities that E. amylovora could use to enter the specimen.

Don’t forget to remove water sprouts or suckers from the base of the tree as well, since those are especially vulnerable.

When you prune to shape a tree, try your best to maintain an open canopy.

Without adequate ventilation within a plant’s canopy, there’s nothing to keep moisture from building up and fostering the growth, multiplication, and spread of pathogens.

Don’t prune too much, though. This can stimulate cut tissues to regrow with a vigorous vengeance, which we know helps fireblight to spread quickly.

And finally, no matter what, when, or how much you prune, be sure to sterilize any pruning tools that you use with rubbing alcohol. You wouldn’t want to spread pathogens via contaminated blades!

Avoid Overhead Irrigation

Since splashing water is one way that E. amylovora spreads, make sure to directly water the root zone of plants rather than their leafy shoots.

If you’re giving the plant a shower from overhead, then you’re doing it incorrectly.

Management Methods

Given the severity of fireblight, the slightest infection must be met with aggressive management, lest your plant eventually perish.

There’s no known cure for fireblight, only ways of controlling it. So if you find it in your garden, then you have my condolences. Here’s what you can do:

Prune Out Infection

You should definitely prune away diseased twigs, branches, and cankers, but the “when” must be carefully considered here.

For the most part, it’s best to prune during winter dormancy. Pruning during the growing season – especially in spring, when cankers are oozing – may lead to sucker growth and transferring the pathogen from cut to cut, spreading the disease even more.

An exception to this rule is when a few young specimens in your orchard exhibit relatively small amounts of infection. In those instances, you should prune out infected tissues as soon as they become apparent.

Young trees set terminal buds later than mature ones, allowing for a larger window of disease progression.

Plus, eliminating these few areas of disease in an otherwise healthy orchard is worth the possible risk of spreading it further, in my opinion.

Regardless of the season, don’t prune in wet weather. You’re much better off waiting until it’s relatively dry.

When you’re removing diseased branches, it’s important to make your cuts at least a foot below infected wood, if possible.

Yes, this means cutting well into healthy-looking wood, but it’s a necessary sacrifice for ensuring the health of the rest of the plant.

When you’re done pruning, take what you’ve cut out of the orchard for burning or burial.

While you’re at it, do the same with any mummified fruits and dead twigs that lie on the ground, as they may harbor the pathogen as well.

Use Chemical Controls

I gotta be upfront: chemical controls aren’t super effective in controlling fireblight.

Depending on your budget and how invested you are in your infected trees, using them may not even be worth it to you. But if you’re looking for any possible advantage, then read on.

Chemical controls are essentially preventative at best, and there’s no way of guaranteeing the thorough coverage of an entire plant.

Plus, it would be a bit of overkill to bust them out for a tree’s first year of fireblight – it’s best to save them for when a specimen has had the disease for multiple years.

Streptomycin, and copper-based sprays such as Bordeaux mixture, can be applied at at bloom time once daytime temperatures begin to exceed 60°F.

Applications can continue as frequently as every three days while daily highs of 65°F and humidity of 65 percent are maintained. But these chemicals could damage fruits, so be sure to cease applications well before fruits form.

Additionally, promptly spraying these chemicals on the weather-damaged sections of trees after severe storms can fortify those entry points against pathogens.

Remove Infected Specimens

There’s no official rule for when to remove a tree that’s infected with fireblight. Rather, you should constantly be weighing the pros and cons of salvaging a tree versus removing it outright.

Removing a tree that could have been saved is always a bummer, no doubt about it. But trying to save a lost cause that stays alive long enough to infect your other, disease-free trees… that’s no fun, either.

If the trunk and roots start to exhibit signs of infection, then the tree is usually a goner.

Additionally, a tree that’s had fireblight for several years should also be given the ax. And lastly, if the blight makes an infected tree look like it survived a wildfire, then it should probably go, as well.

Once you remove the sickly specimens, feel free to replace them with more resistant varieties, or even entirely non-rosaceous plants.

E. amylovora doesn’t live free in the soil, there’s no need to wait X amount of years for the pathogens within the soil to die – you can promptly plant a new specimen! Just make sure there isn’t any nearby plant detritus that could harbor the bacteria.

You’ll Do Alright Against Fireblight

…especially now that you’re armed with the know-how necessary to prevent and combat it!

This doozy of a disease can be quite menacing, especially if you’ve got delicious apples, pears, or plums on the line.

But prompt and decisive action will go a long way in protecting your orchard from fireblight, and I believe in you all! Digital nods of respect all around!

Still have questions about fireblight? Lessons that you’ve learned the hard way? The comments section awaits your thoughts.

Trying to keep your rosaceous fruit trees happy? Here’s the low-down on some potential threats to their health: