Cardamine spp.

I think native plants don’t receive the attention they deserve. And I get it.

It’s hard to say no to a dramatic peony or stalwart hosta, but there has to be some room for the less dramatic, but no less lovely natives in our gardens, right?

Take toothwort, for example.

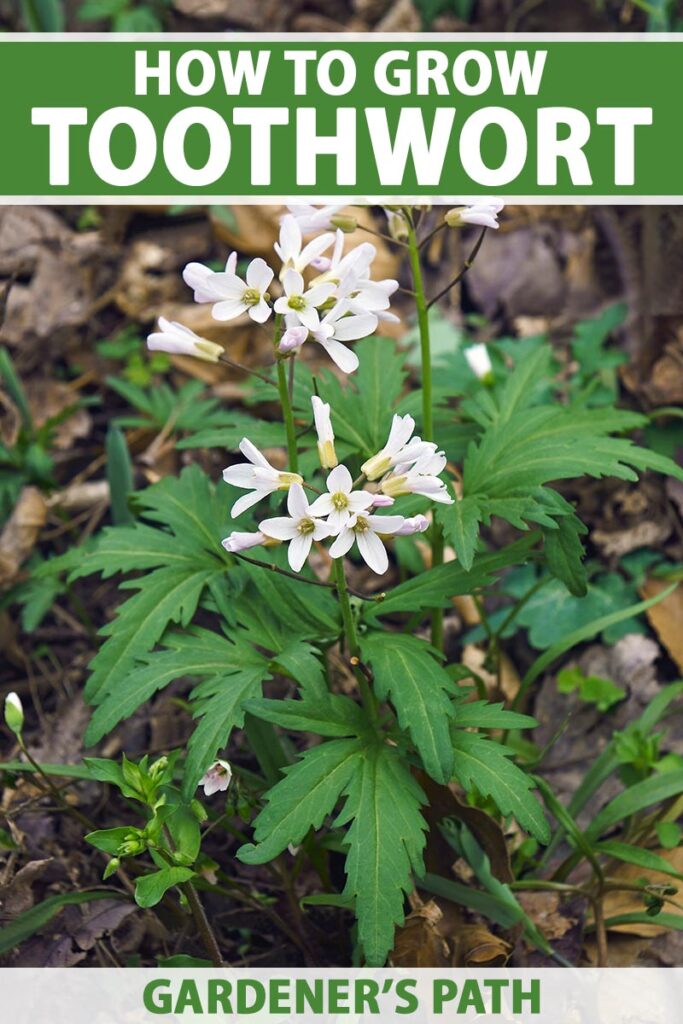

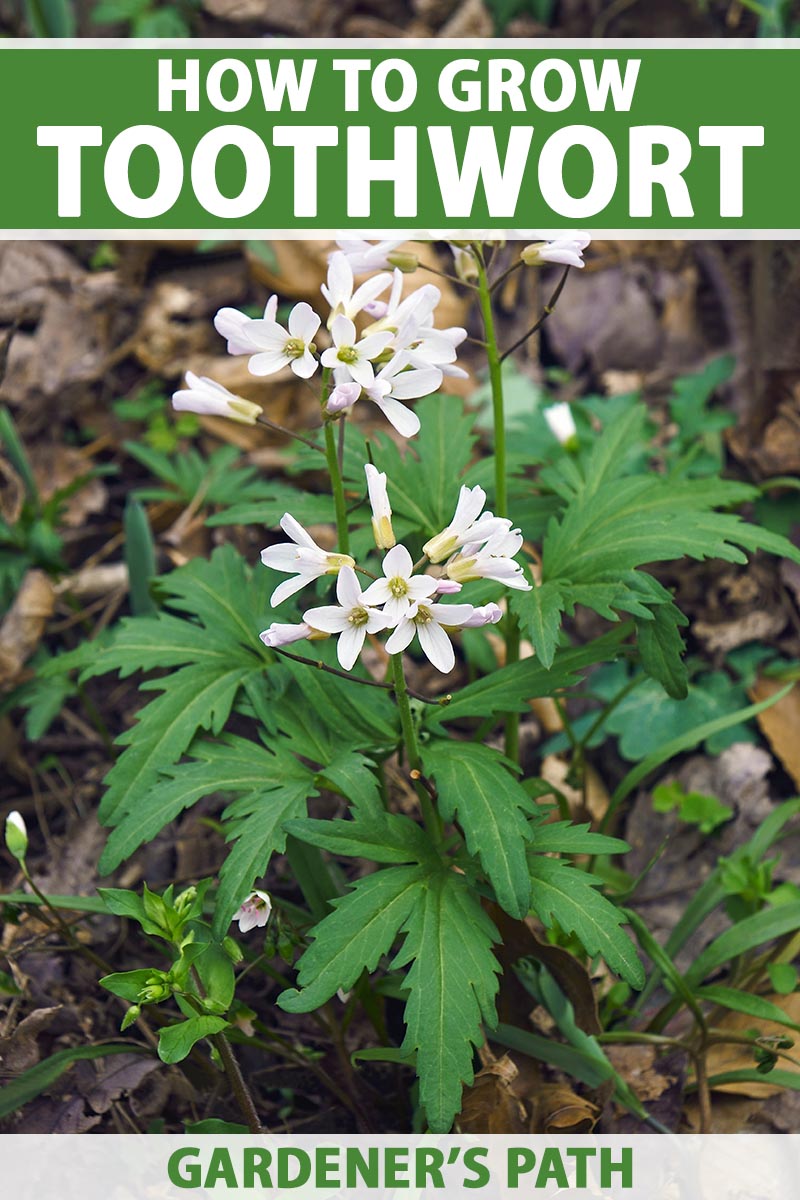

These spring charmers offer up delicate, bell-shaped flowers that add life to shaded or moist areas. On top of that, they’re indispensable to wildlife such as butterflies and bees.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Good old pepper root, as it’s also called, has been humbly popping up out of the woodland leaf litter spring after spring across the globe while the roses and sunflowers have been soaking up all the attention.

Those of us who love nature and recharge by taking a walk in the woods are always looking for ways to bring a bit of that beauty home. Toothwort is an excellent place to begin.

To help you bring some of the wilderness to your garden, we’re going to discuss the following:

What You’ll Learn

Spring is an exciting time. There’s a reason that poets wax on about the reawakening of the world and artists try to capture that spirit on canvas.

Each little element that I can add to the garden to make spring feel that much more thrilling helps me shake off the winter doldrums and emotionally stretch my limbs for the coming warm days.

Toothwort might be quieter in the garden than some other flowers, but it’s every bit as vital for bringing in the woodland joy.

Oh, and did we mention it’s edible? Yep, it can bring joy to the kitchen, too.

Enough with the love letter to toothwort. Let’s jump in!

What Is Toothwort?

Toothworts are brassicas in the Cardamine genus, sometimes inaccurately classified as Dentaria, which are closely related plants known as cresses.

In the western part of North America, toothwort is one of those plants that is in botanical classification chaos.

Experts can’t seem to agree on which species should be shuffled into the Cardamine genus and which should be described as Dentaria.

For now, angled (C. angulata), alpine (C. bellidifolia), Nuttall’s (C. nuttallii), California (C. californica), western (C. occidentalis), little western (C. oligosperma), and yellow-tubered (C. nuttallii var. gemmata) toothworts are all classified as Cardamine species.

They’re common in low-elevation, forested areas near streams.

East of the Rockies, things are a little more organized. Look for cutleaf (C. concatenata, formerly D. laciniata), forkleaf (C. multifida), slender (C. heterophylla), two-leaf or crinkle root (C. diphylla), and large (C. maxima) toothwort.

Plants in this genus have been used by numerous native tribes, including the Algonquin, Cherokee, Iroquois, Micmac, Menominee, Ojibwa, Navajo, and Cheyenne, to reduce fevers, cure a headache, calm the stomach, ease a cold, reduce gas, calm a sore throat, and as an antidote to poison.

Toothworts are sometimes called cuckoo flowers because they start to bloom when the cuckoos start singing in the spring. They’re also called bittercresses, further confusing the classification.

Generally, the toothworts grow about a foot tall or slightly taller, with heavily toothed, whorled, medium-green or grayish-green leaves.

Plants have a basal rosette of leaves with long stems supporting the flowers and the siliques (aka the seed pods). Some have alternating leaves but others, like C. diphylla, have opposite leaves.

Most are spring ephemerals but some are evergreen, such as C. trifolia. Most are perennials but some are annuals or biennials. All need cool, moist conditions.

The clusters of four-petaled flowers these species produce are either pink, pale purple, or white and emerge in the early spring. The anthers are bright yellow and the sepals have a hint of purple.

After the flowers fade, which happens in about two weeks, they’re followed a month later by slender seed pods.

These oblong seed pods explode when they’re ripe, shooting seeds as far as six feet away.

These plants get their name from the fact that they have canine tooth-like growths on the stems underneath the ground.

The growths resemble teeth so distinctly that if you found one sitting around in the woods separate from the plant, you’d assume you’d found the fallen tooth of a raccoon or lynx.

These plants are an important food source for the mustard miner bee (Andrena arabis).

They’re also hosts to the falcate orangetip butterfly (Anthocharis midea), and serve as the only host of the West Virginia white butterfly (Pieris virginiensis).

Cultivation and History

Toothworts are part of the mustard family (Brassicaceae), along with vegetables like kale, Brussels sprouts, and cabbage.

Unlike those plants, toothworts haven’t been extensively cultivated – which is a shame, because they’re both attractive and delicious.

Plants in this genus occur across the world, but cutleaf toothwort, also known as pepper root or crow’s toes, is native to eastern North America and is one of the most commonly cultivated varieties.

There are even a few cultivars out there that you can often find at nurseries.

There are several species that have been brought to North America from Europe as well that you’ll find in stores. We’ll talk about all that in a bit.

Pepper Root Propagation

In the wild, toothworts reproduce by shooting their seeds out into the world or spreading underground via rhizomes.

Not all toothworts eject their seeds, some just drop to the ground. But either way, they’re spreading the love far and wide!

You can propagate them through the same methods, by sowing seed or dividing the roots. You can also buy seedlings at specialty nurseries.

From Seed

Propagating toothwort seed is a challenge, but if you time it right, you’ll set yourself up for success.

When the seed pods split, harvest the seeds and sow them right away. They don’t store well. For that reason, you should harvest the seeds yourself rather than buying them, unless you can be sure they were recently harvested.

You’ll know it’s time to nab the seeds when the pods are plump and brown. If they’re starting to split, act fast! Cut open a pod and scoop out the seeds.

Now you have two options. You can either put them directly in the soil after harvest or you can sow them in pots indoors after a period of stratification.

If you go the indoor growing route, the seeds can be kept for a month or so and then placed in moistened sand in a resealable container like a zip-top baggie or a small glass container.

If you store them, allow them to dry in a protected area and then keep them in a cool, dark place in an envelope.

Place it in a warm area with temperatures consistently between 60 and 80°F for 30 to 60 days, then move the container to the refrigerator for two to three months.

The timing here depends on when you can sow them outdoors in the spring. You’re looking for a few weeks before the last predicted frost date in your region.

If you can sow early in the year, you might do 30 days of warm temperatures followed by 60 days of cold. If you have to sow later in the year, go for 60 days warm and 90 days of cold.

After this period of warm/cold stratification, it’s time to sow your seeds in a container.

Fill a three-inch container or a six-cell tray with potting soil. Sow at least two seeds in each pot or cell about a quarter-inch deep. You want to plant at least two seeds because the germination rate for these is usually low.

Moisten the soil and keep it moist. It will take a few weeks, but if you did everything right, the seeds will germinate and you’ll see seedlings popping up.

Move them into an area with bright, indirect light. Keep the soil moist until the seedlings are a few inches tall and the last predicted frost date is about a month in the future.

Now it’s time to harden off the seedlings.

If you’ve never hardened off seedlings before, it involves gradually exposing seeds to the conditions that they’ll be growing in.

Pick up those seed trays or pots and take them outside during the warmest part of the day. If it’s well below freezing, don’t take them outside that day, but right around freezing is fine.

Put them in a shaded area for an hour, then take them back inside. The next day, put them back out in that spot for two hours. On the third day, do the same for three hours.

On the fourth day, put the seedlings in a spot where they’ll receive dappled sunlight.

Add an hour to this routine in that spot for the next three days. Now they’re ready to be transplanted, which we’ll describe below.

From Divisions

If you want to take a part of a wild plant, make sure you have permission. It’s pretty easy to identify these plants in the wild when they’re blooming, but the leaves are pretty distinct, too.

They have three or five lobes on each palmate leaf, which form at the base of the plant. When the plant is blooming, leaves might extend halfway up each stem, attached by a long petiole.

If in doubt, rip a piece off a leaf and smell it. It should smell a bit like horseradish.

You can divide at any time, but the safest time is when the plants are dormant and all of the above-ground parts are gone. That means you need to identify the plant when it’s growing and mark the spot for later.

Of course, those that are evergreen can be identified at any time of year. They should be divided in the fall or early spring.

Chances are that once you’ve found a single plant, you can dig anywhere nearby and find more, so don’t worry too much about marking the exact spot if that’s going to be difficult for you.

When dividing toothwort, you don’t need to dig deep. The rhizomes are shallow and grow parallel to the soil surface. If you encounter a root, follow it. The roots are light in color, knobby, and jointed.

Dig up as much of the root structure as possible, taking care to keep as many of the stems attached as you can if the plant isn’t dormant. Use a pair of clippers to divide up sections of root.

Remember, the roots look like teeth, and each “tooth” can be separated from the rest, but you’ll have the best luck if each part has several segments and a stem node.

If you’re transporting your roots before planting, wrap them in sturdy paper towels or newspaper and moisten the paper. Keep it moist until you can plant.

Plant each section half an inch deep and six inches apart in prepared soil and water well.

Transplanting

Stores that specialize in native species sometimes carry toothwort. You can also occasionally find European species at nurseries as well.

They’re not challenging at all to transplant. Dig down a few inches into the area where you’re planting and work in some well-rotted compost. Then, open up an area the size of the potting container and gently remove the seedling.

Set it in the hole and firm up the soil around it. Water well. Seedlings should be spaced about six inches apart.

How to Grow Toothwort Flowers

Pepper root provides color in shady spots. Many will even grow and flower under the full shade of evergreens.

That said, you can give them a little bit of dappled sunlight or direct sun in the earliest morning hours and they’ll be just fine.

Some toothworts actually require a little dappled light to do their best, so be sure to check your particular species’ requirements.

Toothwort blooms in early spring before most deciduous trees leaf out. They bloom for about two weeks, and then those magical flowers fade. Don’t deadhead, just let them go and do their thing.

Don’t panic if you don’t see flowers in the first few years after planting. It takes about four years for the plants to start flowering when started from seed.

The rhizomes grow close to the surface of the soil, so you want to be careful not to disturb the soil around the plants. That means taking care when weeding.

Toothworts need moderately moist soil at all times. If you think about the moisture level of the soil in the woods under a canopy of trees and a bit of leaf litter, it’s usually pretty moist, and it doesn’t dry out much.

If you stick your finger in the soil, it should feel like a sponge that you’ve wrung out really well. That’s what you’re aiming for. Much wetter and you increase the chances of root rot. Drier and the plants may go dormant prematurely.

Don’t irrigate once the plants have faded and gone dormant.

There’s no need to fertilize, but you should toss some well-rotted compost onto the soil after the plants have gone dormant, by the start of summer.

Growing Tips

- Grow in full shade to dappled sunlight.

- Keep the soil moist at all times.

- Add compost to the soil after plants have faded at the end of spring.

Maintenance

The rhizomes of these plants grow close to the soil. You need to keep weeds out of the area or they’ll steal nutrients, and disturb the toothwort plants when you go to pull them out.

Spreading a thin layer of mulch over the root zone is a good idea, to help keep weeds away.

By early summer, the leaves will start to turn yellow and fade. Don’t remove them – let the leaves completely die back. They provide nutrients to the roots even as they fade.

When one plant starts fading you’ll know that the rest of them will be close behind. All of the plants will be gone within a week, tops.

Now is your chance to mark where the plants are located if you want to do any dividing or root harvesting later in the year.

If you let the plants go to seed, keep in mind that they might spread into areas where you don’t want them. To be safe, if you plan to harvest the seeds, you might want to tie gauze or mesh bags over the seed heads before they split.

Otherwise, snip off the siliques before they mature if you’re worried about spread.

Toothwort Species to Select

All toothworts taste pretty much the same, so if flavor is your primary concern, go wild. It’s always a good idea to grow species that are native to your area.

Avoid wood bitter-cress (C. flexuosa) and hairy toothwort (C. hirsuta). These are species introduced from Europe, and they push out native toothworts.

Here are the most common species you can find in stores. We’ll discuss which are best for the home garden.

Cuckoo Flower

While all plants in the Cardamine genus might be referred to as cuckoo flowers, it’s C. pratensis that officially holds the title.

Also known as mayflower, this species thrives in wetlands and has become a popular marginal plant for pond gardens.

Just be aware that it isn’t native, so you shouldn’t let it spread beyond your garden if you do grow it.

It has become naturalized in many parts of the US, squeezing out native plants. However, it’s more mild mannered than the two species noted above.

It grows to about two feet tall and is tolerant of wet soil while it’s growing, but not during dormancy. The flowers are bright white with alternating compound leaves.

Cutleaf

Cutleaf toothwort is the most commonly cultivated in gardens and the easiest to find in stores. It’s the species that many people are talking about when they use the term “toothwort.”

C. concatenata has smooth tubers, which makes them easier to clean and use if that’s your goal.

The leaves are heavily serrated and the flowers can be white or pale purple.

‘American Sweetheart’ has olive-gray leaves with silver and purple-black veins.

Narrow-Leaved

You’ll have to look hard to find C. dissecta in stores, but this North American native is worth keeping around.

It has narrow leaves on long stems, which almost resemble petite ferns in the garden.

Starting in their second year, they’ll be topped by petite white flowers on three-foot stalks.

Three-Leaved

C. trifolia is an evergreen from Europe and it’s a pretty incredible option if you need an evergreen bloomer for full shade.

It’s pretty hard to find those, so when you do track down a good one, you should nab it.

It stays under six inches tall and happily spreads without becoming invasive. The leaves come in clusters of three.

Two-Leaved

C. diphylla (formerly Dentaria diphylla) is, along with cutleaf, one of the most common toothworts. It’s native all throughout eastern North America in shady meadows and woodlands.

This plant grows about 16 inches tall and forms a dense mound, which makes it perfect as a ground cover. As you may have guessed from the name, it produces opposite leaves in pairs.

Managing Pests and Disease

Toothworts are basically untroubled by pests and diseases. Their mustardy, peppery flavor even seems to deter deer.

I hesitate to list this as a pest, but the truth is that mice will eat these plants, and it’s a good and bad thing.

Toothwort is an essential part of the white-footed mouse’s (Peromyscus leucopus) diet. Other species of mice will eat them as well.

If you have a healthy patch of toothwort, don’t worry about deterring mice. They won’t destroy your garden. If they bother you, plant alliums near your toothworts.

Best Uses for Toothwort Plants

For a flowering groundcover that amps up shaded areas, it’s hard to go wrong with toothwort.

You could group them in large patches or mix them among other plants that will pick up the slack in the summer, like lungwort, bleeding hearts, astilbe, and toad lilies.

Don’t plant them with other brassicas, though. They share diseases.

The leaves, stems, flowers, and roots are entirely edible. Both have a slightly peppery kick. In fact, I bet you could swap out the rhizome for horseradish and you’d never know the difference.

Harvest the leaves before the flowers emerge. After that, they turn more bitter.

The roots can be harvested at any old time, whether the leaves are present or not. The rhizomes break easily, which is both a positive and a negative.

It makes them a little hard to harvest but it also means that there will be more plants when they split and pieces are left behind in the ground.

The leaves and flowers can be used anywhere you would use mustard greens or horseradish leaves – on a burger, steak, deviled eggs, beets, potato salad, a green salad, stir-fries, eggrolls, you name it!

Blend up the roots to make a horseradish sauce and use it where you would use horseradish sauce.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Perennial forb, spring ephemeral | Flower/Foliage Color: | Pink, purple, white/green |

| Native to: | Europe, North America | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 5-9 | Tolerance | Clay soil |

| Bloom Time: | Spring | Soil Type: | Loose, rich |

| Exposure: | Full to partial shade | Soil pH: | 6.8-7.2 |

| Time to Maturity: | 4 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 6 inches | Attracts: | Bees, beetles |

| Planting Depth: | 1/4 inch (seeds), 1/2 inch (rhizomes) | Companion Planting: | Astilbe, lungwort, hosta, toad lily |

| Height: | 16 inches | Avoid Planting With: | Brassicas |

| Spread: | 12 inches | Order: | Brassicales |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate | Family: | Brassicaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Cardmine |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Mice | Species: | Angulata, californica, concatenata, diphylla, heterophylla, multifada, occidentalis, pratensis, trifolia |

Bring the Woodlands into Your Garden

Nothing compares to a stroll through a peaceful forest in the spring, but bringing toothwort into your garden gives you a slice of the woodlands to enjoy even when you can’t leave your home.

So what kind do you plan to grow in your garden? Will you use it to create a mixed wildflower patch, or as a ground cover for a shady area? Tell us all about it in the comments.

If you’re looking for more shade-loving options, check out these guides next: