Alstroemeria spp.

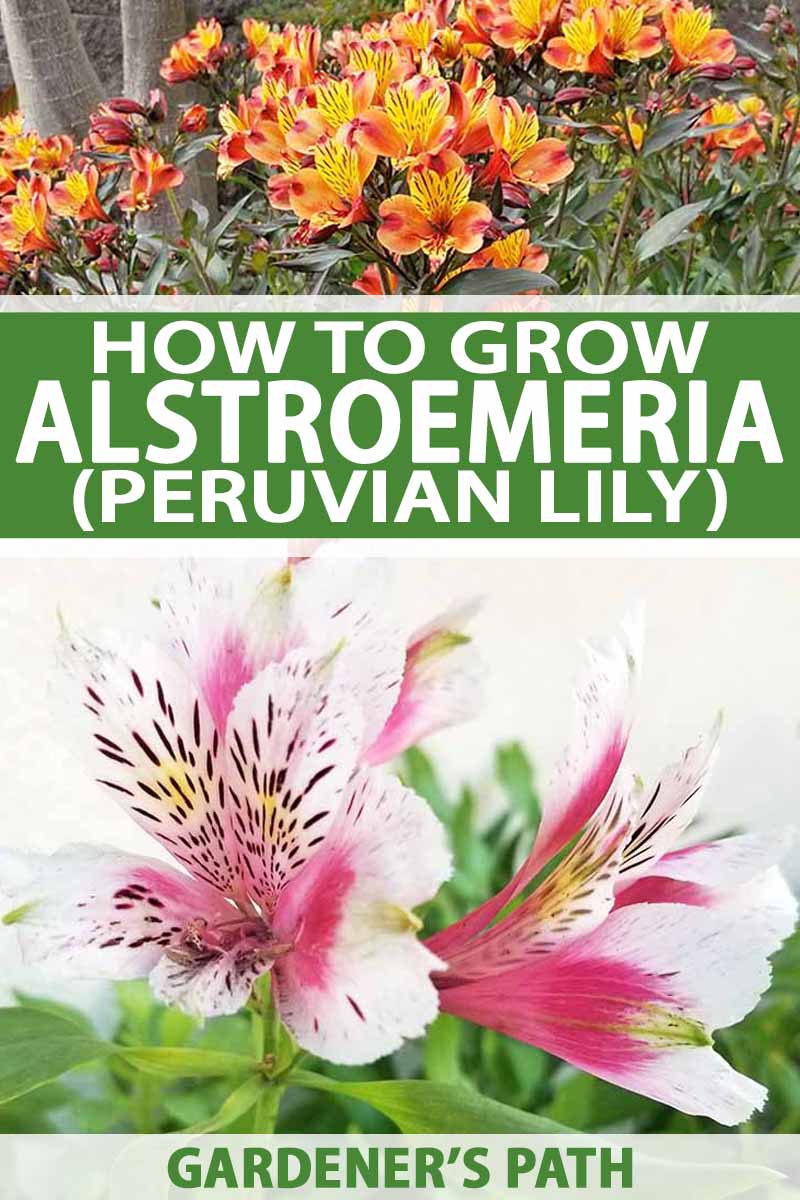

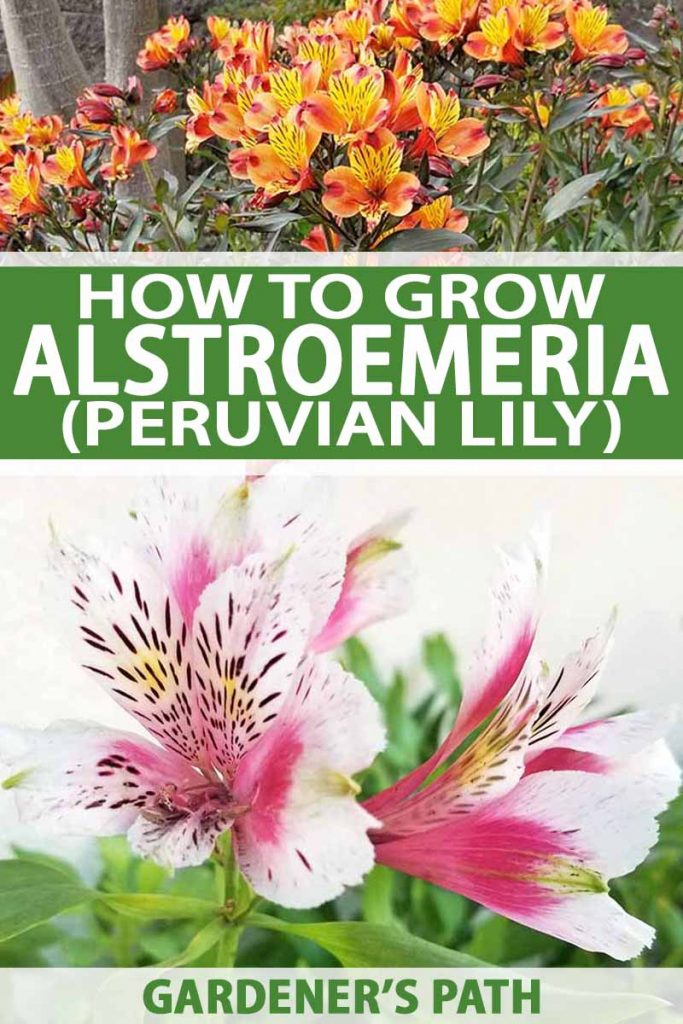

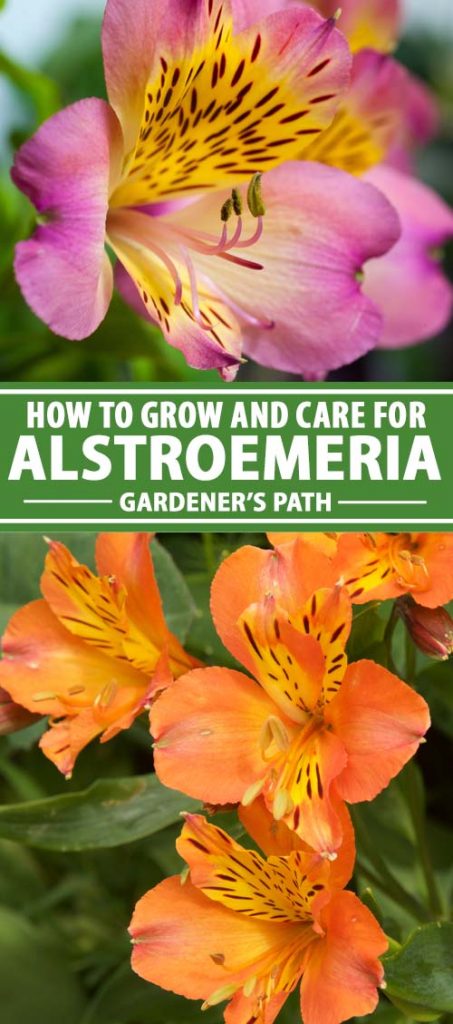

Alstroemeria, also known as Peruvian, parrot, or princess lily, as well as lily of the Incas, is an exceptional cutting garden flower in the Alstroemeriaceae family.

There are about 80 species native to South America, with the greatest diversity in Chile. Thanks to today’s hybrids and cultivars, there’s a rainbow of options available for the home gardener.

Most of the species are perennial, and they grow year-round in USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 8 to 10. With a little mulch in winter, you may even have success in adjacent zones.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Let’s find out all we can and then see where to buy some of our own.

What You’ll Learn

How to Grow Peruvian Lilies

To grow this prolific bloomer, find a sunny to partly shady location.

The soil should be of good quality and on the loose side, so it drains well. Enrich it with compost and add a little sand if necessary.

From Rootstock

Mound the soil to promote drainage as you would to grow squash. Place the tuberous rootstock on the mound and cover it with earth. If there are stems or shoots, they should be upright and visible above the ground.

Tamp the soil down gently to secure the rootstock in place, water, and tamp down again. Maintain even moisture, but don’t let the soil get soggy.

From Seed

Some folks plant seed instead, but often it fails to germinate. The trouble starts once it’s harvested from spent blossoms.

You see, in nature, seed dries out completely and then undergoes a period of wetness, cold, and tumbling about all winter long. It’s this “cold stratification” that enables it to break dormancy and sprout.

To replicate this natural process, you might try the following:

- Harvest mature seed.

- Let the seed dry for several months.

- Soak seed overnight.

- Scarify by rubbing the surface slightly with an emery board.

- Sow in the fall.

As an alternative, you can also provide the necessary period of chilling indoors.

According to Julie Thompson-Adolph in her book, Starting Saving Seeds: Grow the Perfect Vegetables, Fruits, Herbs, and Flowers for Your Garden, you can fill a bag or container with seed starting mix, moisten it, and add seeds that have been given plenty of time to fully dry.

Place it in the refrigerator for two to four weeks to replicate outdoor conditions before sprouting indoors, and be sure to keep the potting medium moist throughout.

Starting & Saving Seeds, available via Amazon

We haven’t tried this particular method for this species ourselves, and time requirements on cold stratification may vary depending on the cultivar. Sounds like a fun winter project to experiment with, and determine what provides the best germination rate for your collected seeds!

Keep in mind that purchased seeds should come already stratified, and ready for planting.

Whenever I start plants from seed, I like to sprout them indoors in egg cartons or seed starting containers. Using a mixture of sand, perlite, and vermiculite is recommended, to promote drainage.

When your seedlings are about two inches tall, transplant them outdoors to the garden or a container with good drainage holes, and remember – pots dry out a lot faster than the ground.

Allow one to two feet of space per plant. Some bloom in the first year, most by the second.

A Note on Hybrid Plants:

Some hybrids do not produce seed at all. They are propagated by the division of their rootstock and bred this way so as not to become invasive. You may divide plants in spring to thin them out, make new plants for other locations, share with friends, or all three!

These plants take time to establish. Help them along with regular watering and a periodic application of slow-release fertilizer. Choose one with a low nitrogen content to avoid a proliferation of foliage with few blooms.

A fun-fact about Peruvian Lily is that it naturally produces some stems that are purely vegetative (non-sexual), while others produce blossoms. With diligent care, by the second year, you’ll enjoy blossoms from summer through fall. And the best part – the blooming is continuous.

In some regions, like southern California, many plants have jumped bed and border perimeters to naturalize in the wild. You can avoid this by “deadheading” spent blossoms to prevent seed fall.

Pick the entire stem at its base, and don’t just remove the top, just in case there’s still some oomph left to make more stems and flowers before season’s end.

Peruvian Lily Species and Cultivars to Select

Are you ready to buy some Alstroemeria plants for your gardens or containers? Check out these beauties!

‘Indian Summer,’ available from Burpee

Enjoy all the colors of a summer sunset with the golden-hued petals and bronze foliage of ‘Indian Summer.’ This 30-inch-tall, 24-inch-wide stunner that’s winter hardy to USDA Hardiness Zone 6.

‘Summer Breeze,’ available from Burpee

‘Summer Breeze’ is a marvel, with its orange-yellow blossoms and variegated foliage. It’s 30 inches tall by 24 inches wide at maturity, and winter hardy to Zone 6.

‘Colorita Elaine,’ available from Burpee

Pink with gold and maroon dots and dashes, ‘Colorita Elaine’ is a dwarf variety that reaches a height of 14 inches at maturity.

‘Colorita Claire,’ available from Burpee

‘Colorita Claire’ is snowy white dwarf variety that is sure to delight at 14 inches tall.

‘Colorita Ariane,’ available from Burpee

‘Colorita Ariane’ is another favorite. This 14-inch dwarf with freckled yellow faces on each blossom is perfect for the garden or container.

Flower Harvesting

When your plants are well established, they will begin to “colonize,” forming numerous mounds along a series of fleshy rhizomes. Each new plant stem that grows shoots straight up from these tuberous roots.

As a matter of fact, you can stimulate plant growth each time you want cut flowers. Here’s how:

Instead of cutting stems at random places with shears, pluck each one at its base, close to the rootstock, to encourage the growth of new shoots. Easy! Then use shears to cut stems to desired lengths.

The exception to this practice is if you’re lucky enough to have flowers in the first year, in which case some folks recommend trimming near the base with shears to prevent uprooting a new plant.

Using Alstroemeria as a Cut Flower

Alstroemeria is prized by professionals and amateurs alike because of its striking, azalea-like blossoms.

It comes in an extensive color palette and has a long vase life. Sturdy stems support hefty clusters of vividly-colored petals that are often striated or flecked by contrasting colors.

In addition, the foliage twists in a unique way so that the underside becomes the top surface. There’s a band of leaves just beneath the blossoms, and then more alternating down the stem.

To display cut flowers in a vase, remove all stem foliage but the top cluster. This serves two purposes: the water stays clean longer, and the flowers receive more hydration.

Once picked, Peruvian lily lasts a good two weeks in water. My first experience with it was using it as a filler flower among larger specimens in tall vases, as well as a stand-alone in small bud vases and bubble bowls.

A Note of Caution:

You should always wear gloves when handling this plant. It contains levels of toxicity that may cause illness if ingested, or an allergic reaction with skin contact.

Would you like to make your own centerpieces for dinner parties? Why not start a cutting garden? Maybe you already enjoy arranging foliage from your yard. If so, this is an exceptional flower that you need to plant.

Overwintering Tips

There are deciduous and evergreen varieties of Alstroemeria available, with some dropping leaves and others retaining them throughout the dormant winter season.

In the temperate zones favored by this plant, you may like the visual interest provided by foliage that lasts year-round. If you are in a fringe zone, pack some mulch around your plants and they may surprise you by holding up just fine.

If you are growing in containers where the winters are harsh, bring them inside before the first frost. Place your pots in a cool location with filtered sunlight, and water often enough to keep the soil from completely drying out.

You may also dig tubers from the earth and bring them inside in pots of soil. However, they don’t like to be disturbed, and you may end up breaking them.

The alternative is to grow Peruvian lily as an annual and replace it with a new and exciting variety, or your all-time favorite, each season.

When spring returns and the frost warnings have passed, divide large clumps of rootstock as desired. Plant them, gradually move indoor containers outside to harden off, and resume regular watering with good drainage at this time.

Pests and Diseases

You should have few disease and pest issues although there are a few to keep an eye out for.

Pests

Alstroemeria plants are generally free of attacks from mammals and other herbivores due to their semi-toxic leaves.

If aphids, spider mites, or whiteflies appear, it’s probably as a result of either overwatering or not watering often enough, and the stress both can cause.

In the case of over-watering, the roots may become waterlogged and rot, snails and their kin may move in, and the plant may be unrecoverable.

If you are under-watering, yellowing leaves will be an early warning sign for you to resume irrigation and ward off pests and vulnerability to disease.

Keep an insecticidal soap on hand, just in case, and apply according to the package instructions in the case of a large infestation.

Here’s a tip: If you’re in for an unusually hot spell, water well and mound mulch around your plants to help keep the ground cool. Otherwise, your flowers may not be as plentiful.

Diseases

The are several fungal diseases and mosaic viruses that can affect your plants.

Three fungus diseases are the most common including: Botrytis blight, Rhizoctonia root rot, and Pythium root rot.

Several mosaic viruses are also a threat to your Peruvian lilies.

Botrytis Blight

This fungal disease, also know as gray mold, makes itself known by fluffy, gray or brown spores on the leaves.

The blight is most common during warm, humid periods, usually when temperatures are between 70 and 77°F.

Botrytis blight is hard to stop once it gets established. Cut out areas of infection and use bleach water (1 part household bleach to 5 parts water) to disinfect your clippers between each snip. Remove and dispose of any plant debris.

Prevent gray mold by spacing your plants to allow good air circulation and by watering around the base of the plants, rather than spraying their leaves and stems.

Rhizoctonia Root Rot

Rhizoctonia solani, the fungus responsible for this form of root rot, attacks during the warmer weather of midsummer by invading at the soil line and transmitting through the stems. If your alstroemeria develops dry and wiry basal stems, Rhizoctonia is a likely cause.

To prevent this disease, ensure that you plant in well-draining soil.

If your plants do show signs of this disease, lightly add some sand and small rocks to the top 10 inches of soil to encourage drainage and add some compost mulch to soak up any excess water. If the root rot continues to spread, remove and dispose of the infected plants.

Pythium Root Rot

Pythium spp. is one of the most common forms of fungal disease in gardens and is found almost everywhere. The spores attack the roots of plants by dissolving the outer cortical layer which leads to decay and blackening of the root.

Wilted leaves and stems, and stunted growth are symptoms of Phythium.

This fungus thrives in heavy, wet soils. Ensure you plant in well-draining soil, and avoid overwatering.

If you notice these symptoms quickly enough, you can successfully treat it by improving the drainage of your soil. Try the sand and pebble method described above, or mix some pine bark into the soil.

Digging small trenches along the side of flower beds may also help to drain excess water away.

If these measures don’t stop the spread of the disease, you may be forced to remove and dispose of the affected plants.

Mosaic Viruses

Mosaic viruses, spread by aphids and thrips can also attack Alstroemeria. The two most common are the tomato spotted wilt virus usually spread by thrips and the Hippeastrum (Amaryllis) mosaic virus usually spread by aphids.

Signs of the tomato spotted wilt virus include irregular lines developing on the leaves coupled with green, yellow, or white spots.

Hippeastrum is identifiable by dark and lighter green mosaic patterns appearing on the leaves.

Mosaic viruses such as these are not treatable.

If your plants do develop symptoms consistent with a virus, remove and dispose of all affected plants. Remember to disinfect any tools that you might have used with bleach water to prevent the spread of this disease.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Tender perennial | Flower / Foliage Color: | Yellow, orange, salmon, pink, rose, purple, red, or white |

| Native to: | South America | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 8-10 (without winter protection) | Soil Type: | Medium, clay, chalk, and sand tolerant |

| Bloom Time / Season: | Early summer through fall | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.0 |

| Exposure: | Full to partial sun | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining but moist |

| Spacing: | 18 inches | Attracts: | Pollinators |

| Time to Maturity: | Current season | Companion Planting: | Lilacs, roses, and peonies |

| Height: | 1-3 feet | Uses: | Cut flowers, beds, boarders, containers |

| Spread: | 1-2 feet | Family: | Alstroemeriaceae |

| Tolerance: | Deer, rabbits, and other wildlife due to toxicity of vegetation | Genus: | Alstroemeria |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Species: | Various |

| Common Pests: | Aphids, spider mites, white flies | Common Disease: | Botrytis blight, Rhizoctonia root rot, Pythium root rot, Hippeastrum (Amaryllis) mosaic virus |

Something for Everyone

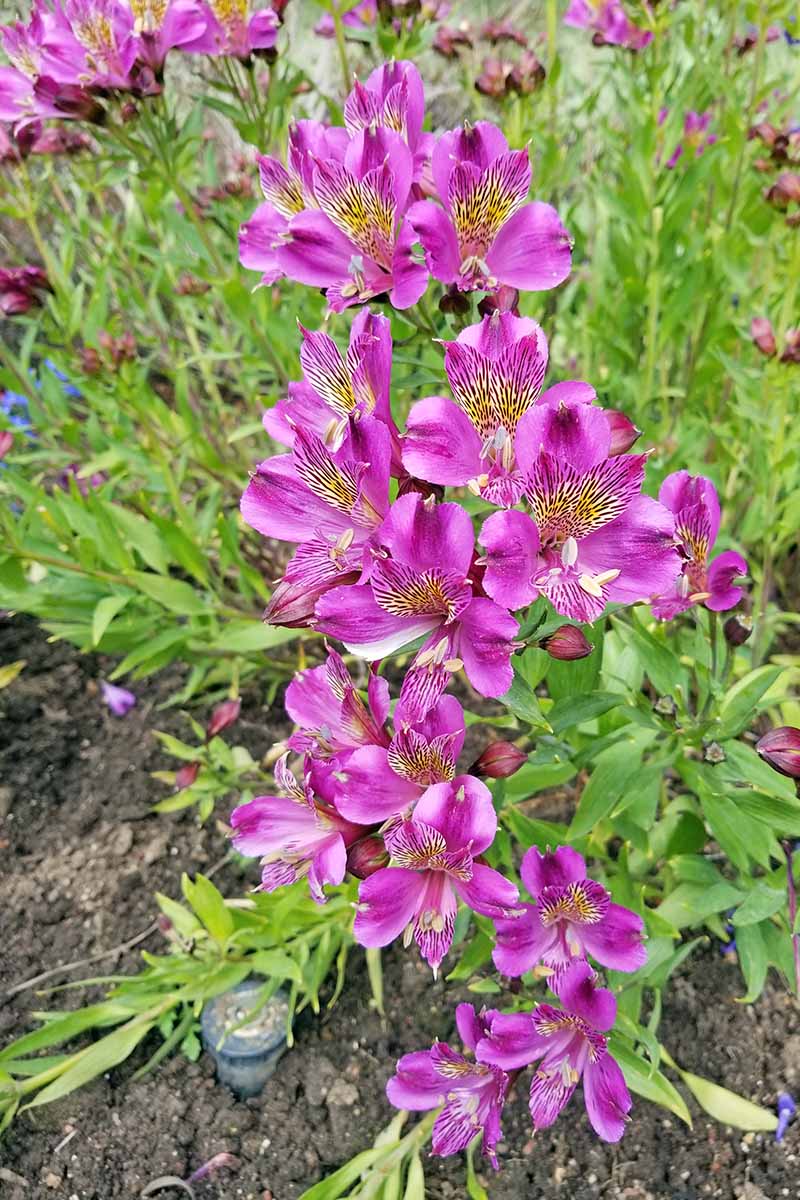

Choices abound when it comes to the vibrant color combinations of Peruvian lily, from 10-inch dwarf varieties to the renowned Ligtu hybrid series with specimens topping out as tall as five feet.

And in addition to being gorgeous, the deep speckled throats of Alstroemeria attract beneficial pollinators, for a lively backyard habitat.

So, what will it be? An assortment of dwarf varieties along a border, tall specimens to anchor the back of a bed, or maybe both? Tell us more about what’s growing in your garden in the comments below.

I live in the upper peninsula of Michigan zone 4. I have about 40 peruvian lillies(alstroemeria) . I love these plants. I have tried bringing them in the house. They do solo in the winter. What is the best way to winter them to hopefully have them for next year.

Hi Pam – What a lovely garden you must have! If there weren’t so many, you could pot them up, trim the foliage down, and leave them in a cool, dry shed. They would need occasional watering to keep them from completely drying out. Or, you could dig up the roots, brush off the soil, and cut away the foliage. The root stock could then be stored in peat moss for the winter. However, with so many, you may just want to trim the foliage to the ground and cover the area with several inches of mulch. The soil must… Read more »

Hi Nan, it says the Peruvian Lillies are toxic to digest – but is it toxic to be used in any skin care products? Do you know if the plant can be dried out?

Hi Michelle –

As highlighted in “A Note of Caution,” Peruvian lily contains toxins. It should not be ingested. Contact with skin may cause an allergic reaction, so using it in skincare products is not recommended. As for drying, you may try suspending stems upside down in a warm, dry place, or pressing them.

Hi, can you recommend sources for 2-3 foot alstromeria seeds or bulbs in vibrant colors like Sunkist orange, pink, etc? The plants I get locally are not growing more than a foot tall. Many thanks for any advice

Hi Kathy,

If the plants are otherwise healthy, I would guess that you are growing the more compact cultivars.

‘Summer Breeze’ is a colorful cultivar that grows up to 2-3 feet tall. It has bright yellow and red bicolored blooms, and variegated leaves. You can find plants at Burpee.

Another possibility is ‘Indian Summer,’ also available at Burpee. This one has yellow, orange, and red flowers. The only pink cultivar they carry is a compact one, that tops out at about a foot tall.

Hope this helps!

Man I am a big fan of all the ranges of purple colors. Is there somewhere you can recommend to purchase these shades.

Thank you

Sal

Hi Sal –

The purple shades are very pretty, and can be challenging to find. Contact your local nursery for sources, or search online for sellers of seeds.

Hello I just acquired this plant from my in laws. It’s been moved from Chula Vista, CA to Banning, CA to now Fallbrook, CA. It is is over 17 years old. No new sprigs or flowers. I must keep it alive as it is from my deceased mother and now my father in law. It is planted in a pot. Do you have any recommendations to keep it thriving?

Much appreciated for your response

Thank you in advance

Hi Dorene –

Heirloom plants are treasures. Be sure to keep the potting soil moist, but not soggy. Never let it dry out completely. During winter dormancy, you’ll find you need to water less frequently.

In the spring, fertilize with an all-purpose liquid houseplant fertilizer per package instructions.

Deadhead spent flower stems to keep plants vigorous.

If you find it necessary to re-pot, choose a container with ample drainage holes. Be very careful not to disturb the delicate roots.

Peruvian lily does best in the garden. To have one potted for 17 years is amazing!

Hi Nan! I loved your article on Peruvian lilies! I have a beautiful yellow lily that I would like to divide but I didn’t see anything about dividing plants. Can Peruvian lillies be divided like hostas?

Thanks Tammy! These can be divided in the spring- see our guide to dividing perennials for tips!

Time to bring my alstroemeria inside for the winter. I turn the potted plants upside down and find a plastic drain device which the plant has wrapped and nearly consumed. I hesitate to pull it out as it will surely disturb the roots… What do you suggest?

Hi Marge –

I think your instincts are right – don’t disturb the roots if you can avoid doing so.

For the future health of your plants, if they have outgrown their pots and the root have become entangled as you’ve described, repotting is suggested to preserve their health in the future. Though you will probably have to cut some of the roots to disentangle them, if you do this carefully and do your best to avoid damaging the root structure significantly, you should be able to restore them to health over the winter. With a little luck and proper care, they should thrive after repotting since the roots will no longer be fighting for space, or reaching beyond their… Read more »

I live in Buffalo, NY and winters are sometimes harsh. I tried to mulch and cover my Alstroemeria with a tent last winter and it did not make it. This year I dug up my new plant, trimmed it to about 3 inches and planted it in peat moss in a clay pot and sprinkled lightly with water. It is in my basement for the winter. Does it need to be watered during this time.

Hi Roberta –

To store alstromeria for the winter, the temperature should be between 35°F and 45°F, and you should water lightly once a month.

Thank you, my Alstromeria was beautiful this Summer. Plan to do the same for Spring 2022!