Lycorma delicatula

If you live in the Mid-Atlantic, you have almost surely heard of the dreaded spotted lanternfly (SLF), known scientifically as Lycorma delicatula.

This invasive planthopper originated from China, where it was observed and appeared in records dating as far back as the twelfth century.

This pest feeds on an extensive variety of economically important plants, ranging from grapes and fruit crops to hardwood trees.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

The major reasons that this pest is so invasive are its enormous host range on plants, and its lack of natural enemies in the US.

This insect lays eggs on a variety of surfaces – including the wheel wells of cars – allowing it to be easily transported to new areas.

Spotted lanternflies are often found on another invasive organism known as the tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima). First introduced to Pennsylvania in 1784, the tree was planted widely in cities throughout the 19th century, and is now found across the US.

While this horrific pest has so far been confined to the East Coast, grape growers on the West Coast are preparing for its inevitable spread.

Here’s what to come in this article:

What You’ll Learn

- US Invasion of the Spotted Lanternfly

- Easy Transport via Motor Vehicles

- Identification, Life Cycle, and Biology

- Host Plants

- Symptoms on Plants

- Honeydew: Why It’s a Problem

- How Homeowners Can Manage Spotted Lanternflies

- Chemical Controls

- Do Not Use Home Remedies

- Growers on the West Coast Are Bracing for an Infestation

- A New Invasive Species

While fighting this pest is not trivial, we at Gardener’s Path will help homeowners learn how to manage infestations by this invasive insect.

US Invasion of the Spotted Lanternfly

The first encounter with L. delicatula in the US took place in Pennsylvania in September 2014. However, the USDA Invasive Species Information Center reports that experts think the fly was present for three to four years in the US before its official discovery.

As of May 2019, 14 counties in eastern Pennsylvania were under quarantine because they are infested with these insects. This includes an area of at least 3,000 square miles!

The situation in Pennsylvania could become dire. According to Jennifer Smith at The Wall Street Journal, if the lanternflies spread throughout the state, they could conceivably damage agricultural crops, forest products, nurseries, and landscape businesses collectively worth $18 billion to the state’s economy.

In 2017, the infestations had spread to nearby states, including Delaware and New Jersey.

In January of 2018, sightings of multiple egg cases and live adults were confirmed in Winchester, Virginia. The insects have since spread into Frederick County.

As of February 2019, Mercer, Hunterdon, and Warren Counties in New Jersey, as well as New Castle County, Delaware, were under quarantine.

The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services established a quarantine for the affected areas in May of 2019.

The unwanted visitors have also been found in New York State, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, although the spotted lanternfly does not appear to have become established in these states as of May 2019.

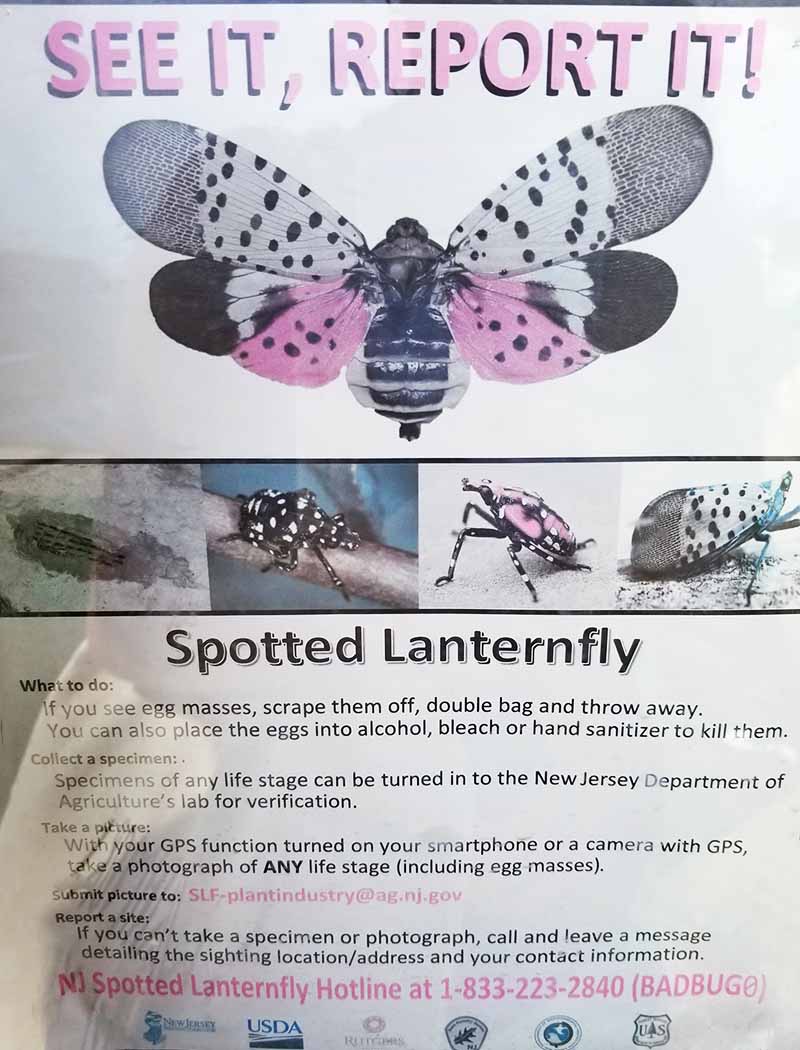

If you live in an area not known to be infested with the spotted lanternfly and you see one, please report it to you county extension agent.

Do your best to kill it (and its friends!) and snap a photo for reporting. Some localities outside quarantine zones have requested that residents submit specimens for identity verification as well.

Easy Transport via Motor Vehicles

Unfortunately, the female spotted lanternflies lay their eggs on any available hard surfaces, such as decks, rocks, trees, playground equipment, outdoor furniture, bricks, wood pallets, and even the undercarriages and wheel wells of cars!

They are sometimes found on firewood, and there is a whole website hosted by an outreach partnership managed by The Nature Conservancy that is devoted to preventing the movement of firewood out of quarantine areas.

As of July 2019, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York require permits for carriers that pick up or deliver wood, plant material, and other items in a quarantine zone.

The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture (PDA) has the power to levy a $20,000 fine if a carrier transports the quarantined pest – even accidentally.

The PDA’s Deputy Secretary Fred Strathmeyer told Greg Grisolano of Landline Today that the state would prefer to not issue fines.

The Penn State University Extension School has an online course on its website to teach businesses how to spot these pernicious garden pests.

Only truckers who load and unload in the quarantine zone require a permit. Those who are just passing through do not need a permit to travel through a quarantine zone, possibly leading to inadvertent spread of these pests.

Identification, Life Cycle, and Biology

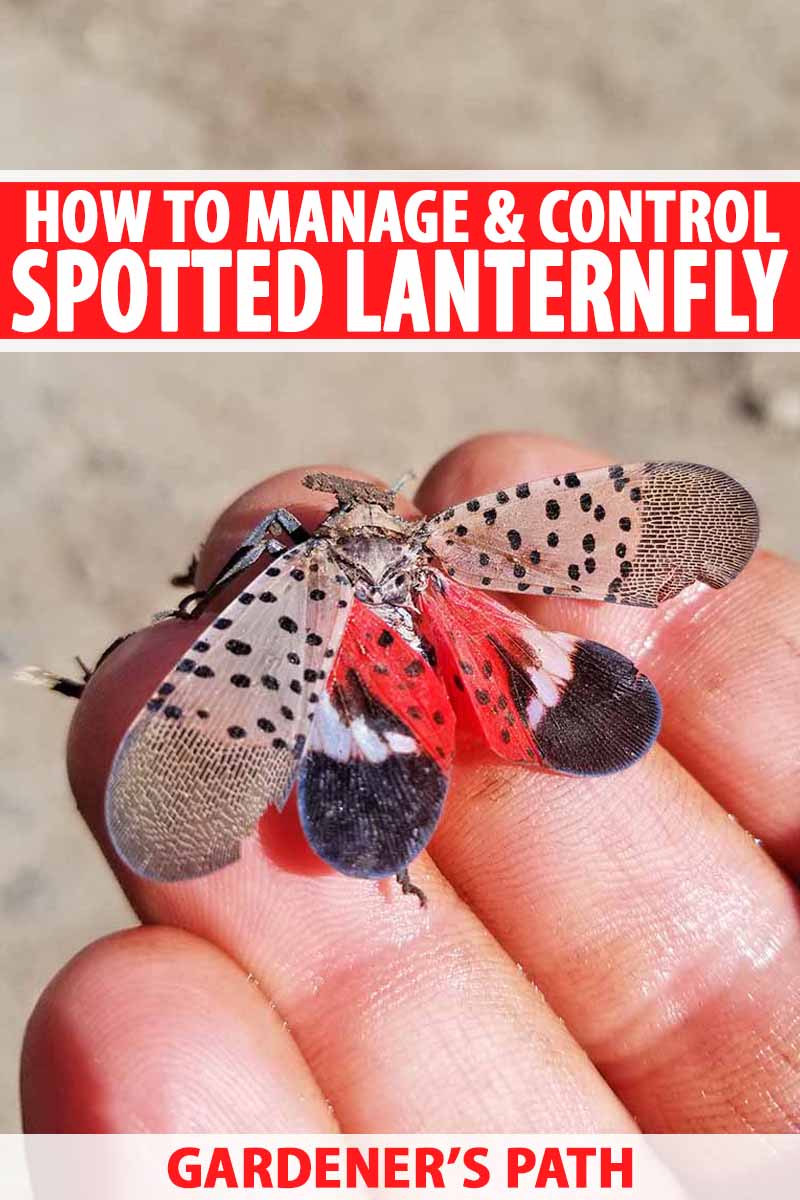

The inch-long adults are easy to identify, thanks to their distinctive coloration.

They have black bodies and gray wings with black spots. The lower half of the bottom wings is bright red with black spots.

If the adults have fed, their abdomens are yellow with broad black bands at the top and bottom.

You can tell an adult female by the red spot at the bottom of its abdomen.

The adults can fly, though they are mainly “plant hoppers” that occasionally travel short distances through the air.

Although the females prefer to lay their distinctive eggs in the fall in trees of heaven, they will lay them on practically any hard surface.

The egg masses look like they are covered in mud, and are about one to one and a half inches long. Each egg mass is composed of 30 to 50 eggs laid in vertical columns of four to seven eggs each.

Depending on when the eggs were laid, they overwinter until anytime between March and June, usually hatching in April or May. They can survive temperatures below 0°F.

The small nymphs that hatch from the eggs are quarter to half an inch long. They go through four immature stages, known as instars.

For the first three stages, they are small black insects with white spots. However, the nymphs in the final phase are very colorful – red with black stripes and white dots.

They are particularly noticeable during this period because of their bright coloration and their large size – at this phase they reach about one inch long.

They are lively and can jump several feet to avoid being captured.

The nymphs morph into adults between July and December.

The adults typically jump, but they do fly to new trees to feed in the late summer.

While the adults feed on the sap in branches, trunks, twigs, and leaves, the nymphs typically feed on leaves and branches.

Host Plants

The spotted lanternfly can infest more than 70 kinds of plants, including trees, shrubs, and vines.

Tree of Heaven

It’s thought that the infestations in the US began with the tree of heaven. This tree is the host that these flies most strongly prefer.

While native to China, these rapidly growing trees were widely planted in much of the eastern US during the 19th century. They were introduced to California during the time of the Gold Rush.

Originally, they were planted to control erosion, but they have also been used as ornamental street trees in many cities.

Since the tree of heaven can grow in a wide range of soils, it has spread throughout the US, and is now considered invasive. It is common in disturbed areas along the sides of roads.

You may need the help of a tree service to remove a tree of heaven, since they can grow to be 100 feet tall. Their trunks can reach six feet in diameter.

Ornamental and Timber Trees

Tree hosts of the spotted lanternfly include oak, sycamore, black birch, maple, paper birch, black walnut, black cherry, white ash, tulip poplar, and willow, just to name a few.

Many arborists and foresters are very concerned about the spread of lanternflies and their potential impact on these valuable trees.

In addition to the direct economic value of many hardwood trees, losing large chunks of forests to this invasive pest could cause irreparable damage.

While this pest can cause damage to ornamental and shade trees, it has not yet been found to kill them.

Fruit Trees and Vines

This pest can feed on a number of crop plants, including apricot, apple, peach, cherry, and plums.

It also feeds on grape vines – a worrying thought for those involved in the $4 billion US wine industry. And that’s not all – the spotted lanternfly feeds on hops, too.

While the insects don’t feed on all types of fruit, they can still affect a harvest by weakening the trees.

Symptoms on Plants

The wounds that the adults and nymphs cause on the plants will ooze, resulting in the classic symptom of a gray or black trail along the plant’s bark.

These insects can suck so much sap that it causes the leaves and young branches to wilt. Symptoms at this point include dieback of the branches, and thinning of the crowns.

Since the adults can’t digest all of the sugar in the sap, they secrete a large amount of it in the form of sugary honeydew.

There can be so much of it that you can sometimes see it falling from the trees on a sunny day!

The honeydew coats the stems and leaves, and can even cover the ground under infested plants.

Honeydew: Why It’s a Problem

The sticky mess draws yellowjackets, hornets, and ants. In addition to being annoying, the presence of these stinging and biting insects complicates the harvesting of crops.

The honeydew also encourages the growth of sooty mold, which can contaminate grapes and other types of fruit, reduce their yields, delay ripening, and reduce their tolerance to cold weather.

The fungi that cause the sooty mold grow so thickly that they can block adequate light from reaching the plants.

Without enough light, the plants cannot photosynthesize properly, and this can lead to their eventual death.

Even other plants growing under trees infected with sooty mold can die due to the lack of light.

Read more about sooty mold identification and treatment here.

How Homeowners Can Manage Spotted Lanternflies

If you live in a quarantine zone, there are several basic steps you can take to keep this invasive pest from spreading to new areas. Let’s take a look:

1. Don’t Transport Them!

Look for the egg masses from late fall to early spring. Be sure and check your wheel wells and under your car. Look for nymphs and adults during the rest of the year.

Don’t park under infected trees or store things under them. And keep your windows rolled up when you are parked.

And once again, do not transport firewood! Even moving mulch, and other yard waste, can be a threat.

Items as mundane as grills and children’s play equipment can harbor the egg masses, so you should check almost any outdoor item before you move it out of a quarantine area.

2. Destroy the Eggs

Keep a close eye out for the egg masses.

When you find them, scrape them off into a solution of rubbing alcohol, very soapy water, or hand sanitizer. Double bag the eggs and throw them out.

You can also smash or burn them, if you choose to. Just be sure to avoid dumping any eggs that you find into the compost pile, or elsewhere that any that may still be viable could hatch out.

Keep in mind that there may be egg masses located on the tops of trees that you might not be able to safely reach. Contacting an arborist or treatment specialist is recommended.

3. Band Trees to Catch the Nymphs

The newly hatched nymphs will walk up the trees to feed on the new growth.

You can prevent this by wrapping your tree trunks in sticky tape to trap the nymphs.

This technique works better on smooth bark than bark that has grooves in it, and it doesn’t work on bushes or vines.

You can make your own tape by putting petroleum jelly on water-resistant paper or plastic, or you can buy sticky tape like Stiky Stuff Adhesive, available from Arbico Organics.

As soon as the nymphs begin to hatch, apply a band of tape about four feet off the ground.

Make sure the tape is tightly secured to your trees, using pushpins or staples, being careful not to damage the tree.

Check your traps at least every other week. You may need to check more frequently if your trees are in a heavily infested area.

Be prepared to reapply the sticky tape frequently.

Avoid Trapping the Wrong Creatures

You might run into issues with birds, squirrels, bats, beneficial insects, or lizards getting stuck in the tape. This happens frequently, and it is known as “bycatch.”

Only apply the tape if you know you have an infestation, or if you have seen the nymphs on your trees.

Steps you can take to minimize bycatch include reducing the width of the band. If you are using a standard commercially available tape, cut it by half or one-third.

Another step is to build a guard out of chicken wire or window screens to keep the larger animals from getting stuck.

And if you do have a stuck animal, don’t handle it yourself. Call your local animal control center, or take steps to safely and carefully remove the band and bring the animal to a local wildlife rehabilitation center.

4. Remove Trees of Heaven and Other Preferred Hosts

Since they prefer to feed on the tree of heaven, you should remove as many of these trees as possible as a preventive measure.

To do this, a professional arborist may apply foliar herbicide such as glyphosate or triclopyr amine to smaller trees in the mid-summer or early fall.

Larger trees may require bark application, either by spraying from the base of the tree up to 12-18 inches, or by making cuts in the bark. This will allow the herbicide to be transported to the roots.

Wait at least a month after herbicide application before removing the trees. They tend to regrow from the stumps as well as root fragments, and these trees have extensive root systems. It may take multiple applications to kill the tree, eradicate the roots, and pull up any young seedlings.

Alternatively, remove the stump entirely. This won’t be an easy job, and professional assistance is recommended.

The tree of heaven looks very similar to several hardwood trees, including hickory and black walnut. But it has a less than heavenly scent. If you break off a small branch, or crush some leaves, you’ll notice an unpleasant smell.

The leaves themselves are unique, each having a pointed end, and two to four notches at the base of each contain glands that give the tree its distinctive smell.

The seeds are another clue, with females producing large clusters of wing-shaped, papery seeds that turn reddish over the summer.

In winter, you’ll need to look at the bark. In younger trees, the heart-shaped leaf scars on the smooth bark are a tell-tale sign, and as the tree matures, the bark becomes darker colored and rougher.

Another recommended tactic is to remove wild grape and oriental bittersweet. There is some evidence that doing so might help to reduce the populations of the pests as these are preferred secondary host plants.

5. Chemical Controls

You have a choice of insecticides for ridding your property of this pest that work in different ways. You should only apply them to trees that are already infested.

Do not treat your whole yard, because you will also kill your beneficial insects.

The following recommended insecticides were evaluated by the Penn State University Extension in March 2019, so it is possible that additional insecticides will be recommended in the future.

Unfortunately, the adults are frequently most active right before fruit trees are ready for harvest – a time when many insecticides cannot be sprayed safely.

Traditional Insecticides

In addition to disposing of any nymphs or adults that you are able to trap and kill manually, application of insecticides will help to prevent their continued spread.

There are various insecticides shown to be effective in controlling spotted lanternflies at different stages of their development.

Ovicides

An ovicide is a chemical that kills the eggs of insects. Preliminary research and testing on ornamental trees suggested that JMS Stylet Oil killed most of the egg masses that it was sprayed on from February to April, in the period before they started to hatch.

You can buy organic JMS Stylet Oil from Arbico Organics.

Contact Insecticides

These are the kinds of insecticides that you are probably most familiar with.

If you spray this type of product directly on the flies, it will kill them. Or if an insect walks across a treated surface, that will also zap it.

You can apply these sprays yourself. If you are spraying a tree of heaven, be sure to spray around the base of the tree, since the adult insects like to congregate there.

Bifenthrin and zeta-cypermethrin are insecticides with excellent residual activity, which means they keep working for some time after application.

Carbaryl is very effective against the spotted lanternfly but its residual activity is classified only as “good” by Leach, Biddinger, Krawczyk, and others at the Penn State Extension, so you may need to reapply more frequently.

However, this insecticide is one of the few contact insecticides that controls the spotted lanternfly and can be used safely on vegetables.

Malathion has poor residual activity and is not recommended.

Systemic Insecticides

In contrast, systemic insecticides are applied in such a way that they become present within the host plant, and when an insect feeds on it, it is killed.

These chemicals are less of a threat to beneficial insects than the contact insecticides.

Systemic insecticides can be applied in a number of different ways, depending on the chemical. Many are applied as soil drenches. Some types are sprayed on the trunks of trees, or the leaves. Pest control professionals may be able to inject some types into your trees.

These compounds take a while to move into the trees, so they should only be applied during periods of active growth. Summer is the best time to use this type of insecticide. Do not apply it in the late fall or winter.

Depending on which insecticide you use, you may need to apply an additional compound that allows the active chemicals to penetrate into the tree. Homeowners can buy a product called Pentra-Bark, available via Amazon.

Systemic insecticides are effective for longer periods than contact insecticides. They can typically persist and remain effective for up to several months.

Combined Systemic and Contact Insecticides

A number of insecticides act in both manners. Keep in mind that the ones referenced below should not be used on edible plants.

Both dinotefuran and imidacloprid are commonly applied as soil drenches.

Imidacloprid should be applied after trees have finished blooming in the spring, so it will kill the nymphs without affecting bees and other pollinators.

In contrast, dinotefuran should be applied in mid-summer through early fall to kill the adults.

Always be careful to avoid contaminating water supplies. Don’t use these compounds if the soil is sandy or if there is a shallow water table in the area.

The contact insecticides Tau-fluvalinate and Tebuconazole are used as spot treatments to spray trunks, branches, and leaves as needed.

Organic Insecticides

Most organic insecticides act on contact. While they have documented effectiveness ranging from good to excellent against the spotted lanternflies, they have poor residual activity and will need to be applied more frequently.

There are a number of different compounds you can use that are safe for vegetable plants.

Insecticidal soaps are a classic way of controlling pests. One such product is BONIDE® Insecticidal Soap RTU, available from Arbico Organics.

Neem oil is a widely used organic insecticide that is also available from Arbico.

Natural Pyrethrins

Spinosad is a microbially-based insecticide that is highly effective against certain pests, including the spotted lanternfly.

You can buy it as BONIDE® Captain Jack’s Deadbug Brew, available from Arbico Organics.

6. Create a Trap Tree

This strategy produces a tree that is highly desirable to the flies and treats it with systemic insecticide, so it will kill the pests!

Get rid of all the female tree of heaven plants in the area, and keep a male tree to lure the flies to it.

The spotted lanternfly will feed on either sex, but the female trees can produce as many as 300,000 seeds a year and repopulate the property. Therefore, they are purged, and ideally only male trees are left.

You can tell the trees apart by inspecting the flowers.

Healthy male trees produce larger quantities of flowers, which have a foul odor, and only the female trees produce fruit, yellowish papery seeds that can remain on the trees until late fall.

The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture provides detailed instructions on how to kill the trees, which readily grow back.

Treat the tree with the insecticide dinotefuran, so it will kill the lanternflies that feed on it.

This approach works best between June and August because the new adults emerge during this period and seek out a tree of heaven to feed on.

In addition to purging the majority of the invasive trees of heaven in the area, establishing these bait trees is a key strategy of the joint efforts between the USDA and the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture.

Do Not Use Home Remedies

The internet offers cures for every problem, and the spotted lanternfly is no exception. We’re here to provide you with the best advice recommended by experts, strategies that have been tested by professionals and that are proven to work.

Penn State University Extension strongly recommends against the use of home remedies, which can sometimes do more harm than good.

Such treatments as boric acid, vinegar, dish soap, salt, garlic, chili, and vegetable oils are ineffective against this insect, and could harm humans, pets, and plants.

While these compounds may seem harmless enough, let’s look at dish soap as an example. It can contain a tremendous number of chemicals, including solvents, surfactants, and foaming agents.

In addition to the possibility of harming beneficial insects, you could burn the leaves of your plant if you spray dish soap on it on a sunny day.

And it gets worse! Boric acid is toxic, and exposure to high concentrations can harm or even kill humans and animals. Even pepper sprays can cause health problems if they get in your eyes or on your skin.

Most importantly, they won’t work against these pests.

Growers on the West Coast Are Bracing for an Infestation

While California is a whole continent away from the infestations on the East Coast, the ability of the flies to hitchhike as egg masses has growers and researchers alike on high alert.

The state is acting proactively by performing research on potential biological controls for the spotted lanternfly.

Biocontrol experts Mark Hoddle and Kent Dawne received a $544,000 grant from the California Food and Agriculture Department to research/test effective spotted lanternfly biocontrol agents in April 2019.

These researchers are piggybacking on comparable work being conducted on the East Coast.

Stakeholders are particularly concerned about the numerous high-value crops in the state, including grapes, walnuts, avocados, and pistachios. California is also the fourth largest producer of wine in the world.

The hope is that with the current quarantine in place, the knowledge obtained by this ongoing research will facilitate the containment of the spotted lanternfly.

And California is not the only western state to be worried – Washington and Oregon have substantial agricultural industries that could also be hard hit by an infestation.

A cautionary tale is that of South Korea. It only took three years for these pests to overrun the country after their first occurrence in 2004.

This is most certainly a case where knowledge is power! It’s up to gardeners and growers to be on the lookout for these pests, to take the necessary steps to eradicate them, and to report any sightings beyond the bounds of established quarantine areas.

A New Invasive Species

For an inch-long insect that was only recognized in the US in 2014, the spotted lanternfly is a significant pest.

Its host range of over 70 plants, combined with its lack of natural enemies in the US, has helped it to spread across eight states – all the way from Virginia to New England.

It is imperative that citizens in the affected areas – as well as areas where the pest has not yet arrived – know what the insect and its egg masses look like.

This pest is a known hitchhiker, and this knowledge can help prevent the inadvertent transportation of the insect to new areas.

The spotted lanternfly is expected to spread from Pennsylvania to the West Coast, but experts are already preparing for an onslaught and hope to be able to keep this insect at bay.

Do you live in a spotted lanternfly quarantine area? Have you spotted any on your property? If so, share your experience with us in the comments.

For more information on emerging insect infestations, such as the spotted wing Drosophila and the Asian citrus psyllid that spreads the lethal citrus greening pathogen, we recommend these articles:

- Using Organic Methods to Control the Spotted Wing Drosophila

- What Is Citrus Greening Disease?

- How to Control Fruit Flies in the Garden and Indoors

Photos by Matt Suwak. © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. With additional writing and editing by Clare Groom and Allison Sidhu.

Please don’t encourage the use of the spotted lanternfly paper tape on trees. People are not using it properly. They are not using the proper wire cage around the tape which helps prevent “by-catch.” Instead of showing tape with only lantern flies stuck to it…try showing tape with bluebirds, woodpeckers, and squirrels stuck to it. It’s a dangerous product and more needs to be done to either educate the public or ban its use.

Dear Roberta, Thank you so much for this critical reminder!

I live in the borough of Hatboro PA and have tons of the little black spotted nymph lantern flies in my backyard that I have treated over the past two days covering two of my trees. My one flowering tree is very affected and some branches are already dead and it has attacked my very large beautiful tree. I’m not sure what kind of tree it is but I am in the midst of finding out. So far I wrapped the base and large branches with inside out duct tape and sprayed the bases of the tree with insecticide as… Read more »

Hi Christina, I am so sorry to hear about the horrible infestation on your trees. I would strongly urge you to apply a systemic insecticide as a soil drench. I think it would be difficult for you to treat all of the insects on large trees, and this will kill all of the nymphs. You can buy imidacloprid at Home Depot as Compare-N-Save – Systemic Tree and Shrub Insect Drench. If you still have the insects as the summer progresses, I would suggest switching to the chemical dinotefuran. Please be careful with the duct tape. Could you put some sort… Read more »

1) I was thinking of buying preying mantis as a predator, and there seem to be places that sell this online (both adult and eggs), but read a posting on the internet, saying that the preying mantis that we can buy are mostly asian preying mantis, not native ones. And the Asian ones are larger, also eat beneficial insects. ?? any information on that

2) there seems to be a plastic bad or bottle based collecting structure that one can attach on the tree, but the Pennstate site instruction is kind of hard to understand. any information?

txs!!

Hi Hong, I’m sorry that your plants are under siege! I am not familiar with using praying mantises to control the spotted lanternfly. My guess is that you would need a huge population of them to make a difference, since so many nymphs are present. I agree that the instructions on using the bag or bottle as a funnel are not clear. You might want to stick to the sticky tapes that wrap around the tree trunks. They are supposed to work better than duct tape. You can order them from Arbico Organics. However, it is important to put a… Read more »

Hi Dr. George, This is an excellent article and most comprehensive with excellent photos. 2020 will be the 3rd year we’ve been dealing with SLF on my property in Chester County, PA. My 2 October Glory maples are a favorite of SLF, and have seen them on our tulip poplar and scarlet oak. Doing my best to try to control them, starting with diligent egg casing removal. I’ve never seen Pentra-Bark Systemic Bark Spray recommended on PSU’s website. I’m interested. Has Cornell tested and recommended it?

Hi Barbara,

Thank you so much! I’m so happy to hear that you found the article helpful. I’m glad that you are diligent with egg masses. I’m not sure about Cornell, but I found a Penn State Extension document that mentions Pentra-Bark as an option for homeowners. It’s posted on the Orwigsburg website. It was produced in cooperation with the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture and the USDA, so it comes highly recommended. I hope that helps and wish you the best with your control efforts.

Thank you for the additional link to the website, as well. Take care

Hi, I’m searching for the source of all the photos in this article. Only a few have the name of the photograph written under it – where have they been taken? Thanks.

The ones by Matt Suwak (another staff writer for Gardener’s Path) would have been in the Philadelphia area. The one by Allison Sidhu (our managing editor) would be in central New Jersey.

The others are licensed to us from various sources.

My maple tree must have lanternflies on it. All of my potted plants have this sticky residue. They are houseplants that I put outside for the summer. What can I do to save them? This also includes the hostas I have around the tree.

Hi Marion,

I’m so sorry to hear about your severe sooty mold. That is very common with spotted lantern fly infestations.

Unfortunately, I am not currently knowledgeable about how to manage it, but I will be doing a lot of research on that over the next couple days, so I should be able to get back to you with advice soon.

Hi Marion, I haven’t forgotten about you! It took me longer to prepare for the sooty mold article than I expected. You can actually wash your plants in a soapy solution to get rid of the sooty mold. Add a tablespoon of liquid detergent (any household kind should do) to a gallon of water. Then dip your plants in it or spray them. Wait 15 minutes and then wash it off. It might take several treatments over the course of several weeks to work, since the fungi that cause sooty mold are really tenacious. I hope that will help! Please… Read more »

Hi Dr. George. We have two very large, beautiful maple trees (silver and sugar) on our Wilmington, DE property. This year is the first we’ve started to witness signs and actual SLF insects (nymphs and adults). More specifically we have noticed a significant amount of honeydew sap excrement being dropped on our backyard deck and furniture, which is promoting the associated mildew / mold build up. Being the beginning of September, we are mostly identifying (and killing) adults at this stage. As you can imagine, they are very difficult to spot and kill on trees known for their scaly and… Read more »

Hi Andrew, Thank you so much for your excellent questions! I’m sorry that the SLF has made it to Wilmington. I’ve heard that they are in my old neighborhood in Heritage Park. Injections of imidacloprid will cause a wound, but they are so widely used that they should be safe. The SLF experts at Penn State University say that September is too late to inject the compound – that it should be injected in June and July. It should then protect against the insects for the rest of the year. If you are seeing a lot of honeydew, you should… Read more »

I need help we have a serious infestation. They are congregating under our roof eves by the hundred and on the bushes outside our house. What can we use that won’t hurt our dogs? They keep trying to get in our house. Please help.

Hi Denise, I’m sorry to hear about your infestation. That sounds dreadful. It sounds like you need something to kill them ASAP. There are some options that are certified organic that should be safe for humans and dogs. One of them is spinosad that is an insecticide derived from bacteria. If you can’t find it locally, you can order Monterey Garden Insect Spray in a ready to use form from Arbico Organics. That should help knock down the populations. Keep an eye out for egg masses on your property, though. And please let us know how you are doing after… Read more »

Great article and conversations. My Maple tree bird safe trap is working well. But not well enough. Some SLF appear to fly over it. Does it help to cut back low hanging branches? Are these used by SLF?

Hi Mark,

I’m so sorry for my delayed response. Thank you for your kind words.

That is an excellent question, and I’m having a hard time finding out how high the insects can fly. “relatively high and far” seems to be the answer. Given that, I think it would make sense to cut back the low hanging branches.

And thank you for using a bird safe trap!

I wish you the best in your battle with them.

I am searching to see how to treat my maple tree from the black sooty mold/fungus from the spotted lantern flies. I read your comment to treat plants with detergent but what about trees?

I heard you can use neem oil but have not found any articles yet on how to treat the tree.

Any suggestions?

I tried the Penn State site but I could not find an answer.

Cindy

Hi Cindy,

I think the principle of treating the trees is the same as treating the smaller plants but much more difficult.

We have an article on how to manage the sooty mold, but it doesn’t specify trees.

You might try the Penn State spotted lantern fly hotline. I have found that they answer quickly and are extremely knowledgeable. If you do call, please let us know what advice they provided. The number is 1-888-422-3359.