Drosophila spp.

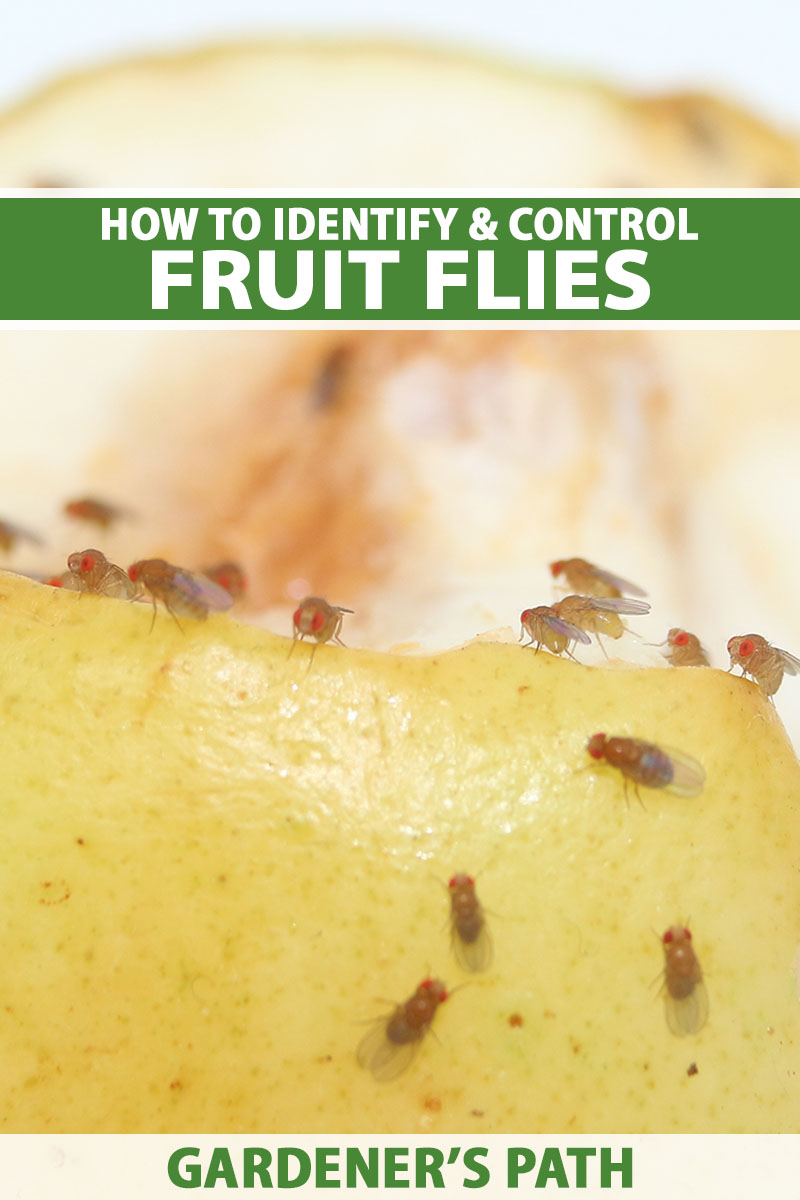

Have you ever left a banana peel in the garbage or a kitchen cloth unwashed for a little too long, and clouds of irritating flies appear, seemingly out of nowhere?

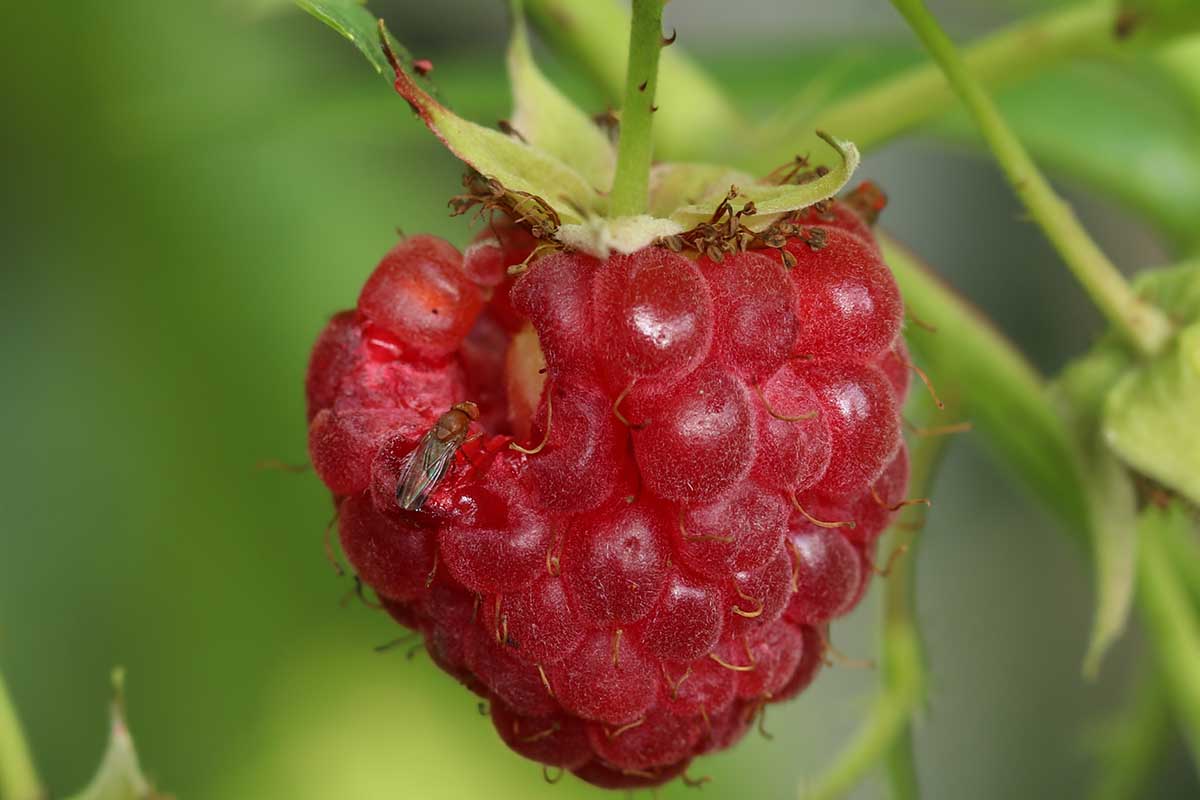

Or, have you been all excited for a fall raspberry harvest only to find the once perfect rubies damaged and turning sour on the canes?

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

If you’ve ever had a fruit fly problem, you know how frustrating it can be.

Luckily, there are a variety of options for dealing with the tiny tan flies that are emerging from somewhere in your home or garden.

Everything you need to know about these little round nuisances is laid out for you below!

Here’s what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Fruit Flies?

We will cover two main types in this article: the common fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), which is the main culprit in your home and better described as a vinegar fly, and spotted wing drosophila (D. suzukii), an important invasive farm and garden pest.

There are many other types, including those that attack citrus trees, gooseberries and currants, and western cherries, but the two we’ll discuss in this article are very common.

In the home, fruit flies are a year-round nuisance indoors, hovering over ripe produce and rotting garbage, with infestations reaching their peak in late summer and fall. They can contaminate food with bacteria and other types of disease pathogens.

In the garden, spotted wing drosophila (SWD) insert their eggs into soft fruits, introducing and facilitating disease, speeding up rotting, and making the maggot-infested berries ugly, unpalatable, and rancid.

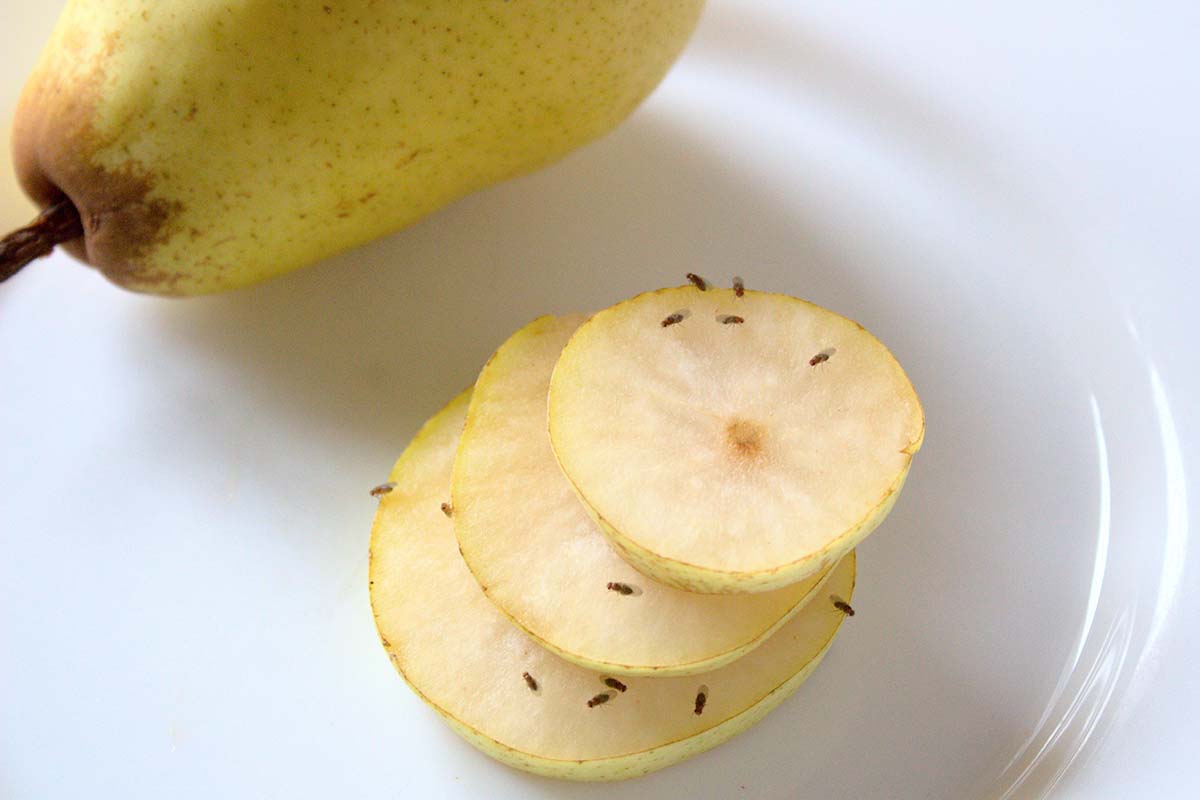

Both like unrefrigerated, ripe, or ripening perishable items, whether that’s on your counter or in the garden.

D. melanogaster merely needs a moist film of material to breed on, such as in drains or the trash, on mops, rags, fermenting foods, and other types of moist organic matter, and thus is attracted to overripe or rotting produce.

However, SWD targets healthy fruits that are often still on the stem, such as blackberries, blueberries, cherries, grapes, plums, raspberries, and strawberries, and it will target damaged thicker-skinned fruits such as apples, pears, and cherry tomatoes as well.

Once infested, rotting is accelerated.

Identification

Adult D. melanogaster are tiny, round, tan flies measuring an eighth of an inch long. They have red eyes, and the males have black stripes and a black abdomen tip, while females only have stripes.

Adult SWD are round, yellow-brown flies with red eyes and dark colored bands on their abdomens, thickening to a black back end.

The females have clear, unmarked wings, while the males have clear wings with a distinctive black spot on the first vein near the wing tip.

Pupae of both species are light to dark brown and tapered, with a hard shell.

Larvae are white, cylindrical, legless maggots measuring an eighth of an inch long, with tapered ends and a distinct head.

Eggs are tiny, half a millimeter long, white to light yellow, and shaped like rice.

Biology and Life Cycle

The life cycles of these pests can be completed very quickly, taking as little as seven days in ideal conditions, and multiple generations can be completed per year.

Females of both species may lay up to 500 eggs.

D. melanogaster lay their eggs in or near the surface of fermenting fruit and other moist areas as described above, while SWD oviposit into healthy soft-skinned, or slightly damaged thick-skinned fruits.

D. melanogaster can breed year-round in your home, but SWD populations peak in August and September, and the adults overwinter outdoors.

The eggs hatch in their respective homes within about 30 hours, and the larvae feed there, completing three instars in as little as four days before dropping to the soil to pupate. D. melanogaster may pupate in the fruit or wherever the larvae were feeding.

In general, less than a month is needed per generation to go from egg to reproducing adult.

Monitoring

You’ll know it if you have a fruit fly problem in your home. Not unlike fungus gnats, they have an annoying presence.

SWD are harder to notice, since they infest plants outdoors.

Symptoms of SWD damage include mold, wrinkling, soft spots and collapse of berry structure, the presence of small larval breathing holes, berry sap seeping from oviposition holes, and tissue scarring.

If you notice these symptoms, however, you are often too late to save the fruit.

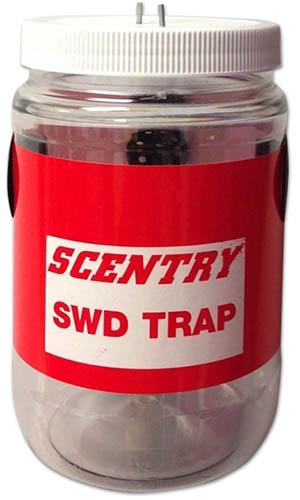

To monitor for SWD before they become an obvious issue, you can capture adults with a homemade trap.

Use a can or bottle with small entry holes (3/16 inch diameter) drilled into the sides of the container about halfway up, making sure to leave a few inches from the bottom sealed to hold liquid.

Add apple cider vinegar and close the lid. The flies are attracted to the scent of vinegar and will find their way inside, but not be able to get out. They will eventually drown in the vinegar but you can hang a sticky card inside to trap them as well.

Hang the trap in tree or vine branches near the fruit, replacing the sticky card and vinegar bait at least once per week, and keeping an eye on the numbers of adults that are trapped.

You can also purchase SWD-specific traps, such as these traps and lures that are available at Arbico Organics.

Some sources will suggest using a paper funnel on top of a jar with some apple cider vinegar in the bottom, and this works to trap flies indoors, but any precipitation would foil that idea, dissolving the cone and/or filling the cup.

Organic Control Methods

There are a variety of methods for mitigating and controlling fruit fly infestations, including strategies to use indoors and out.

Unfortunately, SWD can be a difficult pest to control once infestations become an issue, as the larvae are hard to reach with pesticides.

Once they start feeding, the fruit spoils quickly and becomes unmarketable. Thus, monitoring and preventative strategies are important.

Cultural and Physical Control

Sanitation is a key element of control, both in the home and in the garden.

Keeping a clean kitchen, sorting through ripening fruits regularly, and refrigerating produce if possible, can help to minimize available surfaces for these flies to breed on.

Chilling also slows or stops larval development, giving you time to cut away damaged areas from your harvest and process the rest.

Harvest ripe produce frequently, and do not allow old or damaged fruits to stick around on stems or drop to the ground, attracting the flies. SWD will overwinter in and around old fruit, so be sure to clean up well at the end of the season.

Any overripe produce should be processed quickly, and rotting items should be sealed in a bag and thrown out or left in the sun to solarize.

Do not compost or bury any with suspected SWD damage, as pests in immature stages of development can survive being buried up to 18 inches deep.

These flies are not picky, and alternative hosts for SWD include honeysuckle, dogwood, and a large variety of other wild plants such as wild blackberries.

These plants can provide food extra early or late in the season and overwintering areas for the pests, so consider keeping the areas around your garden free of possible alternative hosts.

SWD populations tend to be low in the spring, especially in colder areas, so choosing June strawberries, and early-ripening blueberries and raspberries allows you to get ahead of the peak infestation periods.

Agfabric Insect Barrier Bug Net

Exclusion techniques can be effective as well, such as protecting plants with 80-gram insect netting like these Agfabric Insect Barrier Bug Nets, available at Home Depot.

Biological Control

In general, augmentative biological control – or in other words, applying predators, parasitoids, or pathogens – has not been perfected for SWD, so cultural and pesticide methods are the only highly effective methods known for use in an integrated pest management (IPM) strategy.

Biological control efforts for dealing with SWD are mainly implemented by conserving the good bugs already found in nature.

These beneficial insects include predators such as ants, damsel bugs, earwigs, pirate bugs, and spiders. Certain parasitoids attack these flies as well.

If you’d like to try adding beneficials, there are several known to attack fruit flies. Keep in mind that, used alone, these aren’t proven to provide full control but may help your cause!

Rove beetles (Dalotia coriaria), available to order from Arbico Organics, are soil-dwelling predatory insects that will attack fruit fly larvae and pupae.

They do exist in the wild, but they can be applied intentionally to guarantee their presence.

NemAttack Beneficial Nematodes

Beneficial nematodes such as Steinernema feltiae and S. carpocapsae will attack the pupae as well. NemAttack Nematodes Combo Packs containing these are available at Arbico Organics.

Organic Pesticides

Spinosad products are effective, such as Monterey Garden Insect Spray, which is available at Arbico Organics.

This product is toxic to bees, so apply in the evenings or early in the morning before they begin flying for the day.

Kaolin clay or potassium silicate products can provide some control.

Arbico Organics carries Surround WP, which can be applied to protect crops that are prone to infestation from egg-laying insects.

Agro-Pest is another option, a combination of repellant and insecticidal oils that is safe for beneficials and effective against SWD. You can find it available at Arbico Organics.

Chemical Pesticide Control

Using chemical pesticides in your home is not recommended, especially since good sanitation practices are very effective against common fruit flies.

Cyantraniliprole, malathion, and cypermethrin are just a few of the available pesticides that are effective against SWD.

Keep in mind that many of the plants you might wish to protect or treat with harsh chemicals also require pollination to produce fruit, so if you must apply something, always spray outside of bee foraging windows.

Combating Fruitarian Insects

I can’t say I blame these flies for enjoying the same sweet and colorful delicacies that we love to grow and purchase.

The luscious morsels that are waiting to be eaten on your counter or weighing down the stems of your plants are a tempting treat for anyone.

Problems arise, though, when we decide to have a berry snack and find them ruined by hungry maggots.

Luckily, there are ways to prevent infestations and deal with these pesky bugs.

We’ve all had fruit flies mysteriously appear in the kitchen. Tell us what you did to get rid of them in the comments below. And if you’ve ever noticed SWD damage, please share your photos and stories!

While you’re thinking about protecting your fruits, read about other common pests here:

Fruit Flies (and similar creatures) Indoors: easy to control ONLY if you don’t let them get a foothold – easy to do: they flourish in discarded food, so: never (NEVER) leave discarded organics open; put them immediately into a covered container. And, they collect around ripe or ripening soft-skinned organics (bananas, peaches, pears, etc.) but only on thick-skinned organics whose skin has been softened by injury, old age etc; so apples, pomegranates, avocados, unripe bananas, etc.) are very rarely visited by fruit flies, and similar creatures, so: never leave soft skinned or damaged organics uncovered. Use a cover such that… Read more »