I was visiting my daughter out West, and on one of our walks, we came upon what turned out to be prickly pear cacti growing on a hillside by the road.

One of the flattened paddle-like stems, aka cladodes or nopales, had broken off and was lying on the ground.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

We noticed that, unlike some cacti we had seen, it didn’t have long, sharp spikes but rather tufts of small yellow bristles. My daughter thought she could root the paddle, so she grasped it gingerly while I opened my canvas shoulder bag.

I can hear you laughing already.

We didn’t realize at the time that the bristles are called glochids, or sometimes glochidia, and while not long and menacing, they are sharp, irritating, and difficult to remove.

In this article, I’ll discuss glochids, which species have them, and safe handling techniques.

What You’ll Learn

The Spines Make the Cactus

Cacti are succulents with spines or leaves that evolved to withstand harsh desert weather. They deter predators, reduce evaporation, and shield the fleshy, water-filled stems from sun and wind.

They vary widely in traits like texture, shape, size, and color. The spines of Emory’s barrel cactus, Ferocactus emoryi, are ridged and firm.

Those of old man cactus, Cephalocereus senilis, are smooth and hair-like.

Spines grow out of raised bumps called areoles that are evenly spaced on the stems, cladodes, pericarpels (around the flowers), and fruits.

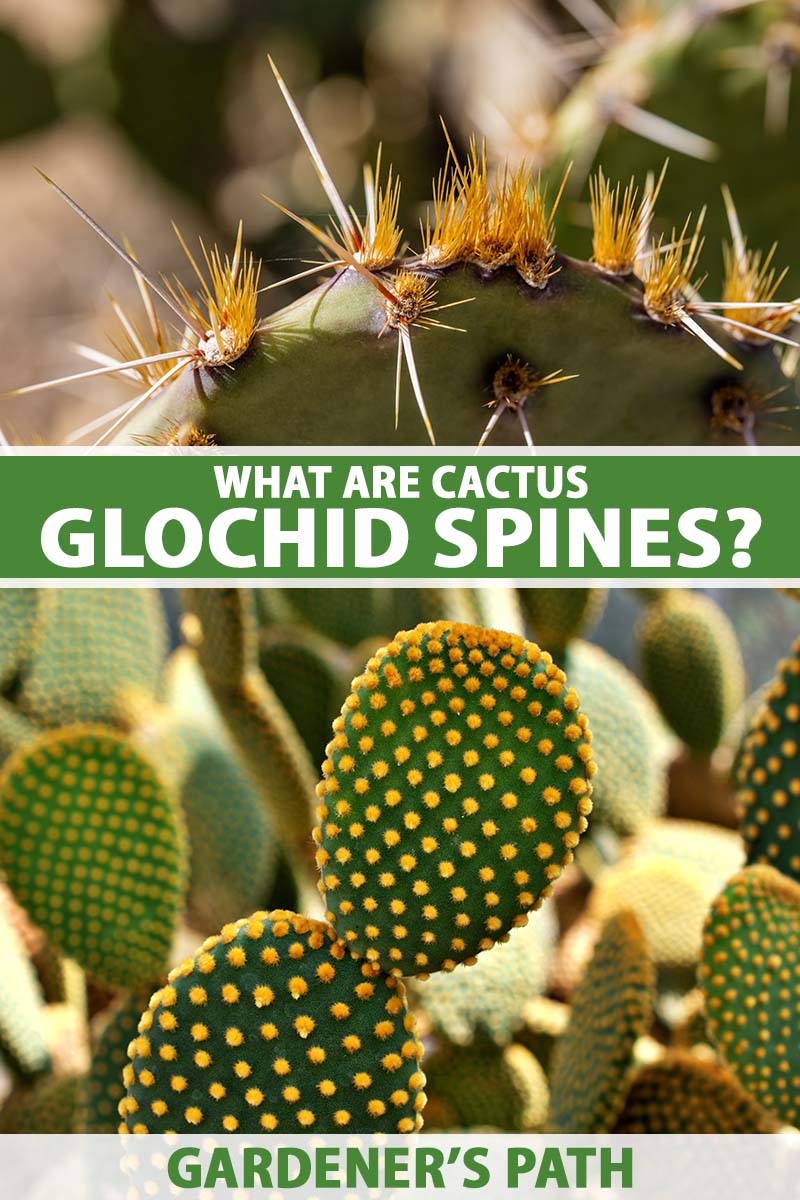

Glochids are small bristles that also grow out of areoles. Unlike longer, smooth spines, they are brittle and detach easily from the foliage. But fishhook-like barbs make them especially hard to extract from whatever they penetrate.

Cacti with glochid spines belong to the same taxonomic subfamily, Opuntioideae. Within this subfamily are five tribes: Austrocylindropuntieae, Cylindropuntieae, Opuntieae, Pterocacteae, and Tephrocacteae.

That’s a lot to take in!

Don’t worry if you find it overwhelming. Because of a high degree of natural hybridization, multiple genera per tribe, and many species, the entire subfamily is still undergoing study to distinguish natural species and best define them.

In 2010, experts proposed that the only true tribes in the Opuntioideae subfamily are Opuntieae and Cylindropuntieae.

Cacti in these tribes have glochids, and the two types common in cultivation are prickly pears, Opuntia spp., and cholla, Cylindropuntia spp. There are subspecies of both types, as well as cultivated varieties.

As of 2021, there were 180 recognized Opuntia species.

Cacti in the Opuntia genus have flattened, segmented stems. Cylindropuntia cacti have round, columnar loosely segmented stems. Chollas have only glochids, while prickly pears can have glochids and large spines or only glochids.

Formerly, species in both genera were classified as Opuntia, because both have glochids and a segmented, branching growth habit. However, pronounced differences warrant classification in separate genera.

An example of a cholla is the teddy bear species, C. bigelovii.

Prickly pears with large spines and glochids include devil’s tongue, O. humifusa and plains prickly pear, O. polyacantha. Examples of species with only glochids are bunny ears, O. microdasys and beavertail, O. basilaris.

Chollas have an unusual trait. The stem segments are loosely attached and densely covered in glochids.

When passersby get too close, the segments cling with a vengeance to fabric and skin. This characteristic has earned the Cylindropuntia fulgida species the name “jumping cholla.”

What’s that, you ask?

Are there spineless Opuntia cacti?

Great question!

At the turn of the 20th century, breeder Luther Burbank developed spineless hybrids by crossing various Mexican prickly pears, Opuntia tuna, with Indian figs, Opuntia ficus-indica.

However, the resulting plants still have glochids, and under drought conditions, they may still grow long spines.

Regardless of species and size, when spines of any type pierce the skin, they can cause irritation, inflammation, and infection.

Damage Control

If you are injured by contact with a cactus, sanitize a pair of tweezers or needle-nose pliers with 70 percent isopropyl rubbing alcohol. Use a magnifying glass and mirror to guide you and attempt to remove all the spines you can see.

If you still feel a scratchy, stinging sensation, the bristles have likely broken and left the barbs behind. Sanitize the affected area with rubbing alcohol. Once dry, apply an antibiotic ointment daily.

A 2010 case study confirmed that spines that remain embedded may lead to infection, inflammation, allergen and toxin-mediated (body’s response to germ infiltration) reactions, and granulomas (nodule formation at the infection site).

Consult a medical professional to avoid complications, as recovery may take months.

On that walk with my daughter, neither of us realized that the nasty little bristles had detached and embedded themselves in my fabric bag and the sweater I was carrying in it.

When we went to lunch, I took the sweater out carefully to avoid disturbing the paddle. I put my arm into the sleeve, and suddenly, it felt like pins were pricking me, and I didn’t know if I was itchy or in pain.

When I took off the sweater and ran my hand down my arm, I had the sensation that there were tiny slivers of glass in my skin.

We soon learned that the innocent-looking yellow bristles were designed by nature to detach readily and wreak havoc in the mouths and on the skin of predators.

Fortunately, I wasn’t skewered to pieces and had no signs of complications. In a matter of days I no longer felt any irritation.

Mind the Spines

We learned our lesson.

The first line of defense when handling a cactus is thick gloves made from a sturdy, cut-resistant material such as leather, nitrile-coated fabric, or rubber. However, even the best still don’t offer complete impermeability.

The second is a barrier material, like a foam packing sheet or a sling made from newspaper, for a firm grip during activities like dividing, potting, transplanting, and hauling home found treasure.

You can add a third protective layer to the process by gently grasping the foam or newspaper with salad tongs.

Paddles Aren’t Portable

Well, I guess most people wouldn’t carry a bristly paddle in their pocketbook. But in our defense, I’ll bet you have a few gardening skeletons in your closet, too.

It’s five years later, and the sweater and tote still serve up the occasional jab, even after repeated washings.

We’ve mentally filed this story under “What Were We Thinking,” right after the one about the well-meaning spouse who snipped the Christmas cactus and added it to the chicken dinner. But that’s a tale for another day.

Keep the two common garden varieties with glochids in mind: prickly pear and cholla. Don’t let the small stature of the sharp bristles fool you. They cause irritation with the potential for infection and require handling with care.

Do you have experience with glochids? Tell us about it in the comments section below.

If you enjoyed reading about glochids and would like to learn more about gardening with cacti, we suggest the following: