Ilex verticillata

I grew up enjoying snowy winters every year in Montana, so when I moved to southern California for college, I missed the snow. A lot.

But then came graduate school in Vermont, where not only did it snow every winter, but plants I hadn’t seen before in Montana popped up along with the snow and cold.

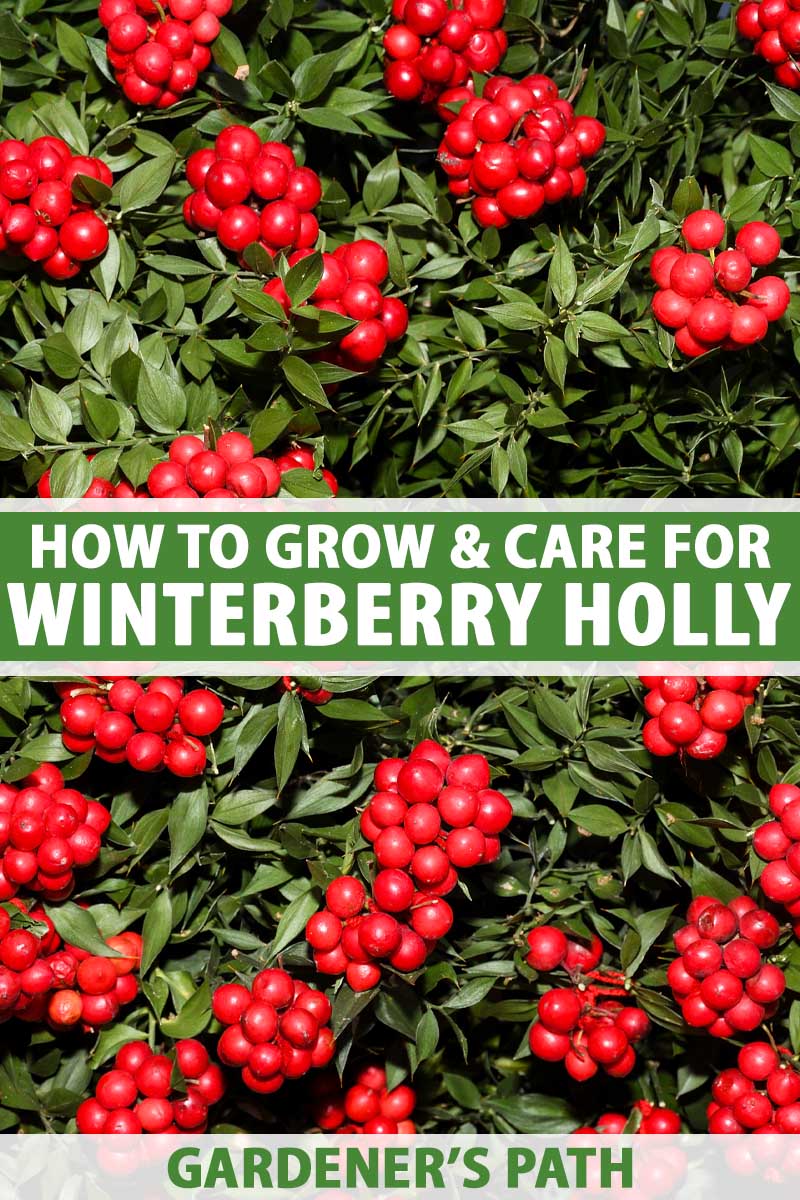

Plants like winterberry holly bushes, bare-branched except for jewel-like clusters of bright berries hanging on well into January, February, and even March.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

While this beautiful woody shrub’s native range stretches from central Florida and Texas and up through New York State and Maine, you can grow it just about anywhere if you live in USDA Hardiness Zones 3 to 9.

Winterberry holly, Ilex verticillata, makes an attractive hedge or addition to a flowerbed at any time of the year, and the bright berries attract birds and small mammals – a good thing or a not-so-good thing, depending on your preferences.

But beware, for these lovely-looking berries are toxic to humans and dogs if ingested. Don’t eat them!

Unlike other well-known holly plants like English holly (I. aquifolium), I. verticillata is deciduous, but its berries cling to the branches for months after the leaves – which often turn a pretty orange, rust, or purple color – drop.

I. verticillata has a rounded growth habit and a mature height of three to 15 feet with a spread of six to 15 feet, depending on the variety.

Want to learn how to grow this gorgeous shrub with year-round appeal?

Here’s what I’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Is Winterberry?

Native to the eastern United States and Canada, winterberry holly thrives in wet, acidic soil with a pH of 3.5 to 6 and grows happily alongside ponds, creeks, rivers, and swamps.

Other common names include Canada holly, common winterberry, and black alder (though I. verticillata is not related to alders).

This species belongs to the Aquifoliaceae family, of which the holly genus – Ilex – is the lone member.

Plants in the Ilex genus are either evergreen or deciduous shrubs or trees that grow mainly in temperate and subtropical zones. The flowers are tiny and hardly visible, but the berries stand out – especially in the case of I. verticillata in winter.

The genus name, Ilex, comes from the Latin meaning “holm oak” or “evergreen oak.” Holm oak, Quercus ilex, has similar-looking leaves, but is unrelated.

Some leaves of plants in this genus have a distinctly glossy, toothed look, like Christmas-card classic English holly, Ilex aquifolium.

Rather than possessing iconic evergreen foliage, the leaves of I. verticillata are lance-shaped and finely toothed but not sharp like English holly. The bark is smooth and gray-brown.

The gorgeous, quarter- to half-inch berries are actually drupes with seeds inside and range in color from red to orange to gold, depending on the cultivar.

Winterberry holly is dioecious, which means each individual plant will bear either male or female flowers. Only female plants produce berries, and one or more male plants that bloom at the same time need to be growing within 50 feet of the females if you wish to see those bright berries on your shrubs.

Thankfully, via the hard work of bees, one male can pollinate up to ten females.

It’s easy to tell the two sexes apart by looking at the flowers – and later in the year, by noting the absence or presence of berries. Female flowers have raised bumps in the center, which form berries when pollinated, and males do not.

If you grow winterberry holly at home, you can leave the berries on the bush as a striking addition to your landscape, and you can also cut branches to bring inside for a cheery addition to a bouquet, or to display on their own.

We’ll discuss more potential uses for these plants in more detail below.

Cultivation and History

Historically, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) people used the bark and leaves to treat various maladies.

Early settlers and colonists noticed it, too. George Washington wrote about it in his diary, saying, “I discovered in tracing it upwards many small and thriving plants of the Magnolio and about and within the Fence, not far distant, some young Maple Trees; and the red berry of the Swamp.”

The “red berry of the swamp” has since been cultivated by plant breeders into several different cultivars, including ‘Red Sprite’ and ‘Winterberry Red,’ which produce red berries, along with their male pollinators ‘Jim Dandy’ and ‘Southern Gentleman.’

For golden berries, ‘Winter Gold’ and ‘Goldfinch’ are popular cultivars. ‘Aurantiaca’ and ‘Little Goblin® Orange’ are well-loved choices for orange berries.

We’ll talk more about a few of our favorite varieties below.

So, how do you propagate these beauties? Keep reading to find out.

Propagation

There are two common ways to propagate I. verticillata: from cuttings, or by division. We’ll cover each of these methods here.

While it’s technically possible to grow the berries from seed, it can take years to grow mature plants that produce berries via this propagation method. You might also end up with a bunch of males and no females, or vice versa.

Plus, trying to grow seeds from hybrid cultivars can result in disappointment, as the characteristics of these won’t be true to their parent plant.

From Cuttings

If you know someone with thriving winterberry holly shrubs, or if you’ve seen a few plants out in the wild, you can easily propagate a new pair of plants by rooting a few cuttings.

Just remember you will need to take cuttings from both male and female shrubs to ensure you have a pollination partner for your female berry-bearing bush.

Softwood cuttings work best, so you’ll want to do this during the spring or summer.

First, prepare an eight-ounce clear plastic cup for each cutting you plan to take, and fill it with a mixture of perlite and peat moss. Moisten the potting medium by spraying it with a misting bottle.

Then, cut three- to four-inch sections of new growth from the mature male and female shrubs.

Using a clean knife or pruning shears, clip away all the leaves except two or three at the very tip of the cuttings.

Bonide™ Rooting Hormone Powder

Carefully scrape away the bark from the bottom half-inch of the cuttings with a knife, and dip each cut end in rooting hormone gel or powder, like this one from Arbico Organics.

With your finger, create a hole for the cutting in the potting medium in each container and place one inside. Tamp the mix snugly around the cuttings.

Set the containers in a warm area with indirect sunlight, and consider placing a dome over each to lock in moisture. Keep the cuttings moist by spraying the potting medium with water at least twice a day.

After six to eight weeks, the cuttings should be growing new roots, which you’ll be able to see through the clear sides of the cups.

Transplant one cutting apiece to eight-inch pots filled with fresh potting soil and place them in a sunny location indoors, or in a greenhouse. Water them every other day or so, or any time the top inch of soil feels dry.

Make sure they get at least six hours of sunlight each day, or eight to ten hours of light from a grow light, which tends not to be as strong as direct sun.

After a year passes, you can start hardening the plants off by moving them outside for an increasing amount of time each day, until they can stay outdoors in indirect light for eight hours at a stretch.

At that point, you can transplant each one into its permanent place in your yard or garden!

Do this when the weather is still warm and the soil is workable – usually in the late summer or early fall the year after initial propagation.

By Division

If you’re looking for a quicker and easier way to propagate a new plant, try growing a new one (or two, preferably – a male and a female) from suckers that are growing next to or near the parent plants. You’ll want to do this in late fall or early winter.

All you need to do is dig out and detach the suckers from their parent plants and transplant each one into an eight-inch pot filled with potting mix.

Water daily or every other day, letting the top inch of soil just barely start to dry out between waterings. Keep in a partly sunny location indoors or in a heated greenhouse. When you see new growth, you can transplant the new plants out into the garden.

Or, you can dig eight-inch-deep holes at least six feet apart in a partly sunny or full-sun location and bury the pots there for the winter. Mulch with straw, and water as described above.

Come spring, you can remove the mulch and the pots, and replant the root balls directly in the soil.

Just remember to plant a male within 50 feet of a female if you want to see berries in the winter!

Transplanting

If you don’t want to propagate a new plant or you don’t have established plants in the area that you can take cuttings or suckers from, you can always purchase potted I. verticillata plants from a nursery or gardening store.

I’ll offer a few suggestions in the section on Cultivars to Select below.

Remember that you’ll need both male and female plants growing within 50 feet of each other, so when you choose a planting location, check the spacing requirements for your chosen cultivars.

Winterberry holly plants can spread six to 15 feet wide, depending on the cultivar. Smaller cultivars can be planted six feet apart, but check plant labels for mature widths and space accordingly.

The best time to set out transplants in your garden is late summer or early autumn, to give the roots a chance to establish before winter sets in.

To transplant a purchased winterberry shrub into your yard or garden, dig a hole as deep and wide as the root ball and amend it with a mixture of compost and peat moss, or some 10-10-10 (NPK) fertilizer according to package instructions.

Carefully loosen the root ball of the plant and remove it from the nursery pot. Place it in its new spot and backfill with soil.

Water thoroughly, and voila! You’ve planted a lovely set of shrubs to serve as an anchor for your flowerbed. Or, add several more plants to create an informal hedge or border.

How to Grow

Winterberry holly should be planted in a part to full sun location, and does best with well-draining soil, although this plant will tolerate extra moisture.

You can conduct a soil test to check that your soil is acidic enough to grow these – it should be in the 3.5 to 6.0 pH range.

If you need to make it more acidic, lay two inches of peat moss on top of the soil and then work it into the top eight to 12 inches of the planting site with a trowel.

You can also apply granular sulphur, according to package instructions to help lower the pH of your soil.

Water new transplants every other day until you notice new growth. Then, slow to watering a few times per week, or after the top inch of the soil dries out.

Don’t allow the soil to completely dry out, however, as these plants are not drought tolerant – without sufficient moisture, they may not form fruit. You can apply a layer of mulch to aid moisture retention.

To keep moisture in the soil and help the roots stay warm and protected from changes in temperature during the winter, mulch the root area with bark or straw.

Growing Tips

- Plant in a part or full sun location

- Make sure the soil pH is between 3.5 and 6.0

- Water new plantings every few days, or when the top inch of soil dries out

Pruning and Maintenance

To make sure your shrub remains robust as it matures, consider planting it in an area where it can grow without restraint, with a natural habit.

It’s best to plant an I. verticillata that grows only as high as you want it to. For example, ‘Red Sprite’ grows to just three feet tall, and its pollinator, ‘Jim Dandy,’ tops out at six feet.

‘Southern Gentleman’ and ‘Winter Red’ reach a height of six to eight feet.

We’ll talk more about each of these cultivars below, but just keep in mind that you should take a close look at the height and spread of different varieties and find a size that works for you.

For the most abundant berries, you really want to prune this species as little as possible, simply removing dead or broken branches in the winter after the plant loses its leaves.

This is because berries grow on old wood, and buds for the next year develop on the current year’s new growth.

If you prune a branch in the spring, you’ll remove buds. If you wait to prune it until fall or winter, you remove those jewel-like berries.

It’s a lose-lose situation! In fact, leaving a bush alone completely (except for removing cuttings here and there) can result in the most fruitful blooming and yields of ornamental berries.

Cultivars to Select

As mentioned, when shopping for varieties to plant, you’ll need a male to pollinate your female plants.

The important thing to note is that they must bloom at the same time so that pollination can occur. So if you choose an early-blooming female, make sure your male cultivar is also early-blooming.

Here are a few of our favorite winterberry holly cultivars for you to enjoy at home.

Jim Dandy

With satiny foliage and an appealing yellow-and-purple autumn color, ‘Jim Dandy’ will make a beautiful addition to your yard.

But take note: ‘Jim Dandy’ is a male cultivar and does not produce berries.

‘Jim Dandy’ is an early-blooming cultivar, producing flowers between late May and early June – which is why he’s the ideal pollinator for early-blooming ‘Red Sprite,’ described below.

Hardy in Zones 4 to 8, ‘Jim Dandy’ grows just three to six feet tall with a spread of four to five feet.

You can find three-inch potted plants available from Nature Hills Nursery.

Red Sprite

For a perfect complement to ‘Jim Dandy’ and his pollination skills, plant pretty ‘Red Sprite’ in your garden for long-lasting color.

She blooms at around the same time as ‘Jim Dandy’ – in late May and early June. The bright red, half-inch berries last through the winter and into early spring.

Plus, if you’re looking for a compact cultivar, ‘Red Sprite’ is your holly. Hardy in Zones 4 to 9, she grows just two to three feet tall and three to four feet wide, with an upright, rounded habit, making her perfect for a flower bed.

In fact, I’ll be planting ‘Jim Dandy’ and ‘Red Sprite’ together in my garden to provide much-needed winter color that won’t overwhelm my small flower beds.

Find plants in three-inch containers online at Nature Hills Nursery.

Southern Gentleman

Late-blooming ‘Southern Gentleman’ satisfies the pollination needs of all your late-blooming female cultivars, including ‘Winter Red.’

With a height of six to seven feet and a spread of six feet, ‘Southern Gentleman’ makes an appealing, informal hedge.

This male cultivar blooms from early to late June and is hardy in Zones 3 to 9.

Winter Red

For a stunning cultivar with abundant clusters of bright red berries, try ‘Winter Red.’ Mature plants have a height and spread of six to eight feet.

Hardy in Zones 3 to 9, ‘Winter Red’ blooms between early and late June, making her a perfect pair for ‘Southern Gentleman.’

You can find three-inch containers from Spring Hill Nurseries via the Home Depot.

Managing Pests and Disease

Luckily for you, winterberry holly is good at withstanding pests and disease.

While squirrels as well as birds love to eat the berries – particularly American robins, cedar waxwings, gray catbirds, wood thrushes, and woodpeckers – they won’t generally eat enough to interrupt your enjoyment of them. Not all at once, at least.

And indeed, the presence of birds and other little creatures adds interest to the garden. It’s not like you are going to eat the berries, after all! (Again, remember that these are strictly ornamental, and toxic to humans and pets).

Other critters aren’t big fans. All cultivars of I. verticillata are deer-resistant, and these plants aren’t typically bothered by insects.

Though problems are rare, be on the lookout for leaf spot and powdery mildew, which aren’t typically fatal, and ensure adequate air circulation with proper spacing between plants.

If you notice the leaves turning yellow, the soil pH might be too alkaline, which is why it’s important to test your soil before planting.

And if you live in a cold location, be careful when you throw salt down on your sidewalks to melt ice, as it can leach into the soil and raise the pH level.

A great alternative to rock salt is traction sand, available at most hardware stores during the winter, which provides traction but doesn’t melt the ice and add an excess of sodium to the earth, either. We use traction sand every winter at our house.

Although winterberry loves moist soil, it isn’t usually bothered by fungal disease.

It can, however, sometimes fall prey to anthracnose, especially in the humid growing conditions of the southeastern United States. Keep an eye out for small brown or tan splotches on the leaves.

If you see signs of anthracnose, remove the affected leaves and spray the entire section of the plant with copper fungicide spray, like this one from Bonide™, available at Arbico Organics.

Best Uses

Winterberry holly provides a perfect backdrop in a flower garden for other perennials. It also looks lovely as a natural, informal hedge or border.

The berries make excellent holiday decorations, and the red ones contrast nicely with the gray-brown bark.

Trim three to five (or more, if you’d like) branches of berries to display by themselves in a vase with water, where they’ll stay fresh for about two weeks. Or add them to a winter bouquet of red roses and evergreen boughs for a cheerful centerpiece.

You can display them in a vase along with cut white lilies and baby’s breath for a perfect contrast.

Another idea is to add sprigs of winterberries to an evergreen wreath for a warm, natural-looking decoration for your front door. Simply use twine to affix two- to three-inch sprigs of berries to the spruce or pine boughs.

You’ll have to pick individual berries off as they turn brown and shrivel, so keep an eye out for that.

And remember that the berries are toxic, so you want to keep these decorations well out of reach of kids and pets.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Woody ornamental shrub | Flower / Foliage Color: | White/emerald green (noted for berries) |

| Native to: | Eastern North America | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 3-9 | Tolerance: | Boggy, wet soil |

| Season: | May and June | Soil Type: | Acidic, loamy |

| Exposure: | Full sun to part shade | Soil pH: | 3.5-6.0 |

| Spacing: | 6-15 feet | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | Same as root ball | Attracts: | Birds, squirrels |

| Height: | 3-15 feet, depending on variety | Uses: | Borders, hedges, backdrops for perennials; cutting for vases |

| Spread: | 6-15 feet, depending on variety | Family: | Aquifoliaceae |

| Time to Maturity: | 2-3 years | Genus: | Ilex |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Species: | verticillata |

| Common Pests: | Leaf miners, scale, spider mites | Common Diseases: | Anthracnose, leaf spot, powdery mildew |

Berry Merry and Bright

There’s nothing better than looking out of the window in the winter and seeing clusters of winterberries against a snowy backdrop.

One day I’ll go back to Vermont and admire all the wild I. verticillata growing there, leaving lovely berries behind for us to gaze at in the winter and for the birds to enjoy.

But for now, I’ll capture a bit of that magic by planting them in my own garden in Alaska.

Have you ever grown a winterberry holly? What’s your favorite cultivar? Let us know in the comments section below, and feel free to ask any questions you may have!

And for more information about growing holly in your garden, check out these guides next:

- Must-Have Tips for Growing Inkberry Holly

- How to Plant and Grow Oak Leaf Holly

- How to Grow and Care for American Holly Trees

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Arbico Organics, Hirt’s Gardens, Home Depot, Nature Hills Nursery, and Spring Hills Nursery. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. With additional writing and editing by Clare Groom and Allison Sidhu.

Excellent stuff. Great details of explanation. I love all Holly berries plants and I will try to get some cuttings and grow this year. Thanks so much Laura. A keen gardener and follower. Have a great beginning of 2021 and looking forward to more information like this. It’s a year from inspiration like yours that makes easy life. Thanks.????

Thank you so much for reading, Laura! I love hollies, too. If you have any questions, feel free to reach out here or on our forum!

The title photo is not Ilex verticillata, it is Ruscus aculeatus.l aka Butcher’s Broom. The next photo is also not I. verticillata, it is Nandina aka Heavenly Bamboo.

They do look similar, don’t they? Butcher’s-broom tends to have just one fat berry and not clusters like Ilex verticillata. You might be right about the second photo, though. I’ll have to check the source. Those two plants look very similar as well. Thank you!

Hello Laura: Wow Alaska! The state with the most earthquakes! Amazing pioneer you are! I have 2 winter berry hollys one in the northeast side and other on the north side. I have given them no special care except planting well when they were small. They are now both at full potential and are glorious in January. February about 3 yrs ago the robins arrived early and consumed all the berries in 2 days. I have 8 bird feeders and lots of birds who return every year if they dont winter here in Rhode Island. It was great to learn… Read more »

Oh wow! Your yard sounds like a gorgeous and life-filled place. Thank you so much for reading! We do indeed have earthquakes up here — we’re still having aftershocks from our big one in 2018. Pretty wild!

Started three bushes in summer of 2021, and this year have wonderful berries on one female, just a few on the other. Male is between them in a large bed. Love the berries already against all the forest around our home. They are Berry Poppins and Mr. Poppins cultivars. Hoping to make more from these as they get larger. This is the best collection of info I have seen, is really helpful.

Thanks for reading, Stef. We’re so glad you’re enjoying your plants!

Thanks for all of the useful info here! I did want to point out, however, that the picture under “How to Grow”, and the picture under “Best Uses” are both of an invasive shrubby honeysuckle, the genus Lonicera. Ilex have alternate buds and branches, and Lonicera are oppositely arranged.

Thanks Ray! Good catch, we’ll look into it and get those updated.