Ilex spp.

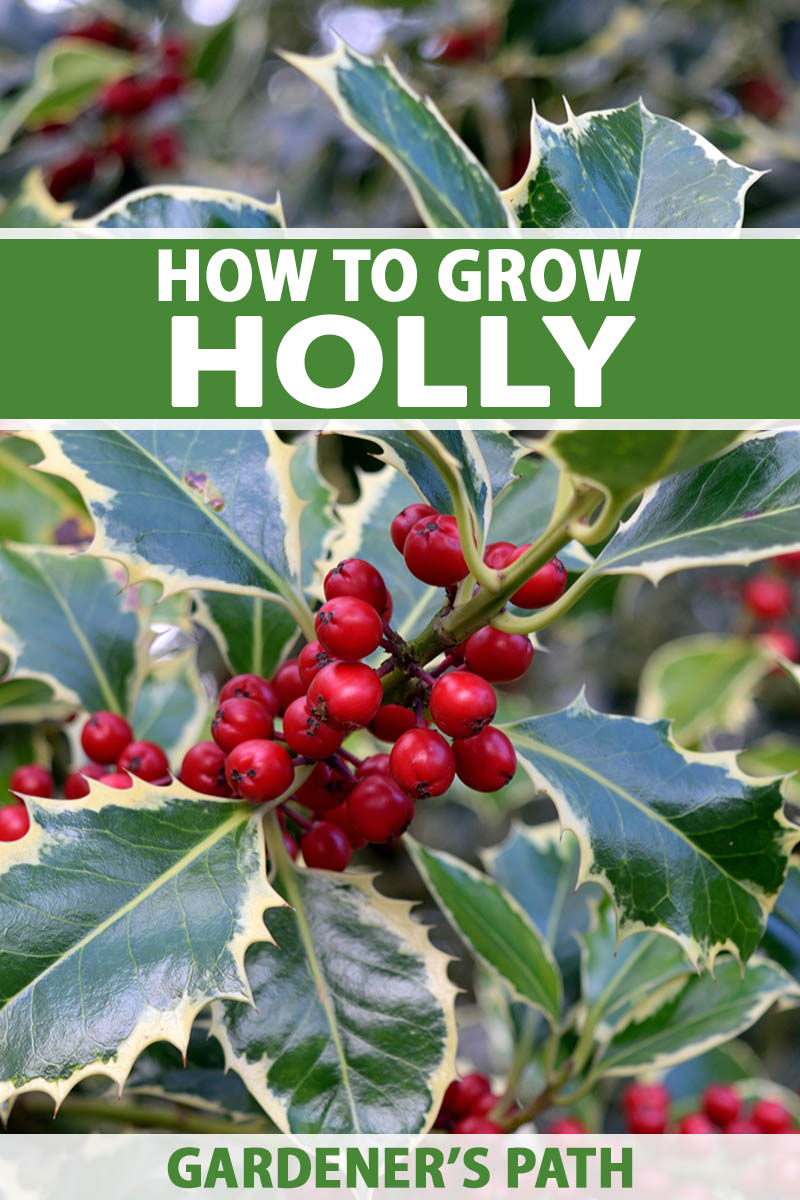

There are some plants that are overhyped and others I totally understand what the fuss is about. You see hollies in lots of gardens, and I think they absolutely deserve their popularity.

Hollies are typically evergreen, provide year-round interest with berries and leaves, and they’re super easy to maintain.

When we talk about holly, most people think about the type with the spiky leaves and bright red berries often used as holiday decorations.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

But there is so much variety within the Ilex genus.

There are smooth-leaved types, those with variegated foliage, some with black or yellow berries, and types that crawl along the ground or grow into tall trees.

If you’d like to learn more about the various plants in this diverse genus, here’s what you can expect in this guide:

What You’ll Learn

Let’s start with what the plants in the Ilex genus have in common.

What Is Holly?

When you think of holly, you probably picture the glossy, alternate, spiky green leaves of common holly (llex aquifolium) – but the Ilex genus includes over 500 species, many of which don’t resemble the familiar holiday greenery one bit.

Some species are low-growing shrubs, others may be climbers, or trees that tower up to 80 feet tall. Some need full shade, and others bask in full sunshine.

There are evergreen types and those that lose their leaves in the fall.

Some have leaves with pointed edges called spines. These sharp bits are a defense against browsing by herbivores.

For plants that grow prickly leaves, the entire plant may or may not have the sharp foliage.

They might have some smooth leaves, a few completely prickly leaves, or some that have just a few spines. If an animal browses on the plant, it will respond by growing new leaves that have lots of prickles, and the spikiest foliage is usually concentrated on the lower part of the plant.

These plants grow natively in North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia in temperate and subtropical climates from sea level up to 7,000 feet in elevation. English holly is the only broadleaf evergreen native to the British Isles.

Most hollies are dioecious, which means the male and female parts grow on separate plants.

If you like the berries, you’ll usually need both a male to pollinate the flowers and a female plant to produce the fruit, though there are some cultivars that are parthenogenetic.

That’s just a fancy word for being able to reproduce asexually, which means no male is required to produce fruit.

Speaking of flowers, they’re usually white and the berries are red, yellow, black, orange, or white, depending on the species.

Technically, the berries are actually drupes, but most people know them as berries, so we’ll refer to them that way in this guide.

Yerba mate lovers might not realize that they’re drinking the dried leaves of a holly plant. Ilex paraguariensis is the species where the beloved South American staple comes from.

Cultivation and History

Hundreds of years ago, holly and evergreen oak trees (Quercus ilex) were classified in the same genus because of their similar leaf shape.

Now, we know they’re not closely related; they just look like they are thanks to the shape of the foliage.

A majority of the species in the Ilex genus are native to North and South America.

Smooth winterberry (I. laevigata), mountain winterberry (I. montana) mountain holly (I. mucronata), American (I. opaca) winterberry (I. verticillata), yaupon (I. vomitoria), and dahoon (I. cassine) are a few common indigenous North American species.

These plants have been and continue to be important to the indigenous people in their native areas, both for the wood and for medicinal purposes. The leaves of many species are used to make tea, though the berries can be toxic.

Depending on the species, various parts of the plants are used to treat fevers, to purify the body, to wash the eyes, to improve vigor, and to ease sleep talking.

As more people began cultivating gardens, they wanted broadleaf evergreen options and hollies fit the bill. The most popular species are, by far, the evergreen ones. There are tons of cultivars that have been around for centuries in Europe, Asia, and North America.

In the US, Christmas holly (I. opaca and I. aquifolium) is grown in the Pacific northwest and shipped across the country for use in holiday decor.

A Ilex few species are endangered, and one, the Indian native Nilgiri holly (I. gardneriana), is now extinct due to habitat loss.

Holly Propagation

Most of us will buy potted transplants from nurseries and home stores, but there are options for propagation if you don’t mind a little work.

You can propagate hollies by seed or via cuttings.

From Seed

It’s possible to grow holly from the seeds inside the drupes, but unless you are using seeds from a species plant, the seedlings might not grow true.

Hybrids, for instance, might have sterile seeds. Some cultivars are patented, so check before you start breeding away. This process also takes a long time.

To propagate seeds, pluck ripe drupes off the tree in the fall. The berries should be their mature color, which varies by type, before you pull them.

If in doubt, wait until mid-winter to harvest because then you can be sure they’re mature.

Pluck out the seeds by using your fingers or a knife to dig into the flesh and pull it off, then rinse off any remaining flesh.

Place one seed about an inch deep in a mixture of equal parts sphagnum moss and horticultural sand. Each seed needs a few inches of space, so either plant them four inches apart in a large pot or sow one seed in the center of a four-inch pot.

Place the pot outside in dappled shade. The seeds need to be exposed to low temperatures, which varies depending on the species. So long as the plant is hardy to your Zone, it will work fine.

Keep the medium moist but not wet, and sit tight. You’ll need to wait through an entire year and into the following spring before you might see any signs of growth. It’s possible that the seedlings might emerge in the first spring, but there’s no guarantee.

Once you see new growth emerging from the medium, gradually move the seedlings into the kind of light the species requires.

For example, if the species needs full sun, you’ll want to move the seedling into full sun over a period of a week, starting with just an hour of exposure the first day and adding an hour each following day.

Keep the soil moist but not wet. If you’ve ever wrung out a sponge really well over a sink, that’s the sort of moisture level you’re going for.

Once the plant is at least six inches tall, you can transplant it as described below. Transplanting should ideally be done in the spring or fall.

From Cuttings

Propagation via cuttings is the most common way for growers to produce plants and it’s the best way if you want to faithfully reproduce the parent plant.

This process is easily done in the spring and works well. Look for a pliable branch that is at least six inches long. The diameter of the branch doesn’t matter, but it should be soft and bendable. This usually means you’ll need to take last year or this year’s growth.

Before you take your cutting, loosen up the soil in the area where you’re planting by adding some well-rotted compost.

While we often start our cuttings in pots, we want to put holly in its growing location straight away because these plants don’t like being transplanted.

Make the cut just below a leaf bud at a slight angle. Remove all but the top two leaves. Dip the end in rooting hormone and poke a hole where you want to plant.

Insert the cutting into the hole by an inch or two and firm up the soil around it. You might want to put a small cage around the cutting if you live in an area with hungry herbivores like rabbits or deer.

Moisten the soil and keep it evenly moist as the roots develop. This can take months, so be patient.

Transplanting

Hollies don’t like to be transplanted. Once they get their roots all dug in and happy, they don’t do well if you disturb them.

To reduce the amount of disturbance, prepare your hole in advance and cut the pot away from the roots if it isn’t compostable. Dig a hole the same depth as the growing pot and two to three times as wide.

Don’t worry, most plants actually do best if they are given a solid base to grow on. You don’t need to dig deeper than the existing root size. But you should dig out wider to make it easier for the roots to expand.

Mix in some well-rotted compost with the removed soil. This loosens the soil and provides nutrients that the plant can use as it becomes established.

Typically when transplanting, I recommend removing some of the existing soil from around the root ball and loosening up the roots a bit, but don’t do this. Try to disturb the roots as little as possible.

Don’t worry, the roots will eventually grow out and into the surrounding soil. It’s a gardening myth that roots growing in a circular pattern because of the shape of the nursery container will continue to grow in a circle.

Place the root ball in the hole you made and fill in around it with the soil you removed.

Firm the soil down gently and water well. If the soil settles, add a bit more. You want the plant to be sitting at the same height it was in the growing container.

How to Grow Holly

Most hollies grow best in partial sun or partial shade. A few cultivars or hybrids will tolerate full sun and a few will thrive in full shade.

All Ilex species need regular water when they’re young and all will require less water during the winter than they do in the growing season.

During the growing season, their needs range from preferring consistently moist soil to allowing the top few inches of soil dry out between watering, depending on the species and even the cultivar.

Check the plant’s water requirements before you bring it home to be sure you can provide what it needs.

If you want the berries, you need a male nearby to pollinate the flowers on the female specimen so the plant can produce the fruit. There are a few exceptions to this, but not many.

You’ll have to hunt the self-fertile ones down. We mention some in the section on best species and hybrids below.

If you grow a male plant, you need one for every ten females or so, and it needs to be situated within 50 feet of the females.

Most hollies like slightly acidic soil with a pH between 5.0 and 6.0, but they will tolerate neutral soil as well. Avoid alkaline soil, which will cause yellowing leaves and stunted growth.

A few species like even more acidic soil and won’t thrive even in neutral soil, so be on the lookout.

If you have alkaline soil, rather than constantly trying to fight your soil pH, grow in a raised bed or container instead.

Similarly, if you have heavy clay, you might want to grow in a raised bed or container. These plants generally won’t do well in wet soil, with a few exceptions.

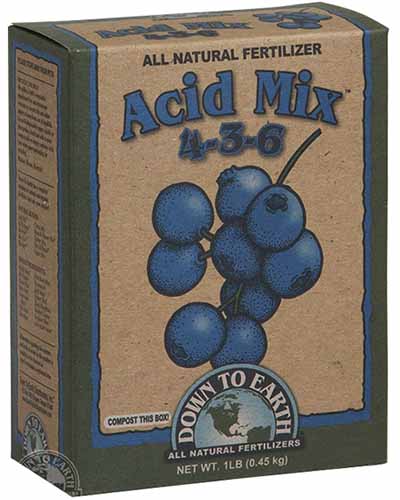

Feed the plants once in the spring with a mild, balanced fertilizer or one formulated for acid-loving plants like Down to Earth’s Acid Mix.

Available at Arbico Organics, it’s my favorite for plants like rhododendrons, blueberries, and hollies because it’s made with cottonseed meal, a waste product that acid-loving plants thrive on.

Growing Tips

- Provide acidic to neutral soil that is well-draining.

- Ilex species generally need partial sun to partial shade.

- To produce berries, female plants need a male plant nearby.

Pruning and Maintenance

All plants in the Ilex genus handle heavy pruning extremely well. If you don’t like the shape of your plant, you can trim it back drastically and then allow it to regrow and reshape it as it grows.

I have taken a 10-foot holly back to the ground and it returned just fine.

That’s not a guarantee, though, so I wouldn’t recommend taking a plant back by more than half unless you don’t mind the risk of losing it.

Keep in mind that a plant that is heavily pruned might not produce flowers or berries the following year.

Don’t move your holly once it’s in place. While these plants tolerate heavy pruning aboveground, they don’t like you messing with the roots. As I mentioned, they don’t transplant well.

Feel free to shear the plants or you can do more judicious pruning.

You should always take off any dead, diseased, dying, or deformed branches. Then, remove whatever you need to provide some shape.

Try to cut the branches in front of a leaf node to encourage bushiness, but the plant will grow around any bad cuts, so don’t stress about it too much.

Holly Species and Hybrids to Select

With so many species in the genus, you know there are lots of options out there. We’ve narrowed it down to just a few of the best for home growers.

Any species that typically has spines will have at least one spineless cultivar, if that’s important to you.

Remember that you should always have a male nearby if you want to produce fruits. We will call it out when there is an exception.

American Holly

American holly (I. opaca) differs from its English cousin (I. aquifolium) in that it has matte leaves rather than glossy ones.

Otherwise, it looks similar, with oval, frequently spiky foliage and red berries that can each be up to half an inch in diameter.

It’s often called Christmas holly because it resembles the English species people have traditionally used to decorate for the holidays.

In the eastern United States, where it grows indigenously, it can reach up to 45 feet tall and half as wide, but most cultivars on the market are much smaller.

You can find I. opaca plants in #3 containers available at Nature Hills Nursery.

‘Satyr Hill’ is an extremely popular cultivar for several reasons. It’s a female, so it produces large, dark red berries in abundance that are evenly distributed throughout the branches.

It also has attractive olive-green, tortoise-shaped leaves that are very large at three inches long and two inches wide.

Bring ‘Satyr Hill’ to your neighborhood and pick one up at Fast Growing Trees in two-quart, two-gallon, and three-gallon pots.

Learn about growing American holly in our guide.

Blue Holly

A clever breeder hybridized pretty English holly (I. aquifolium) with tsuru holly (I. rugosa), known for its unusual leaves, cold hardiness, and prostrate growth habit, to create the glamorous blue holly (I. x meserveae).

It takes its botanical name from its breeder, Mrs. F. Leighton Meserve, who developed a passion for hollies after learning about them at a gardening club lecture in Long Island in the late 1940s.

Thanks to its tsuru heritage, this hybrid is hardy down to Zone 5 and up to Zone 9.

The foliage has a bluish hue, which is where the name comes from, and an elongated oval shape covered in spines along the edges.

The leaves are waxy and somewhat rubbery, making the spines less damaging than those on some other species.

There are several exceptional cultivars, but ‘Blue Princess’ consistently ranks as a top seller. The young leaves are lemon green before deepening to a rich dark blue-green.

The red berries decorate the plant from fall until the birds pluck them from the trees during the winter.

It maintains a petite shape naturally, growing to just 12 feet tall and eight feet wide.

Ready for some garden royalty? ‘Blue Princess’ is available at Nature Hills in #1, #2, #3, and #5 containers.

Chinese Holly

Chinese or horned holly (I. cornuta, previously I. fortunei) is covered in “horned” rectangular leaves covering a shrub that grows up to 20 feet tall, though many cultivars are much smaller. The cheery red berries add color to the winter landscape.

Hardy in Zones 7 to 9, you can shear it into shape to create a topiary or a dense hedge to replace a fence.

Let it grow taller for use as a tree-like specimen. It’s drought tolerant and isn’t harmed by heat and humidity.

‘Needlepoint’ is a cultivar with smooth leaves and an extremely dense growth habit, making it perfect for hedges and living fences.

I. cornuta ‘Needlepoint’ is available at Nature Hills in #3 or #7 containers if you’d like to add one to your yard for some broadleaf evergreen appeal.

Common or English Holly

Good old English or common holly (I. aquifolium) is the one that many people think of when they imagine the plant used for holiday decorations.

It has glossy, oval leaves, often with spiky, prickly protrusions and clusters of bright red berries.

This type is hardy in Zones 7 to 9 and is tough as nails. So tough, in fact, that they might survive and spread too well. They are listed as a noxious weed in Oregon and as invasive in certain parts of Oregon.

But for the rest of us in the right climate, they’re fabulously low-maintenance, with year-round color. They might take up to 20 years to start flowering and fruiting, so you’ll need some patience.

There are over 200 cultivars, ranging in size from two to 50 feet, and some even have variegated foliage with cream or white accents.

You can learn more about how to grow English holly in our guide.

Dahoon Holly

Dahoon holly (I. cassine) is native to the southeastern areas of North America, which means it isn’t phased by heat and humidity.

It grows in swampy areas and in shade, so it’s ideal if you have a soggy area that defies other plants. Just don’t grow it outside Zones 7 to 11 or in a dry, sunny spot.

If left to its own devices, this species grows in a treelike habit and can reach up to 30 feet tall. But it looks equally attractive when trimmed into a hedge or topiary.

The orange-red berries persist through the winter, surrounded by elongated oval leaves that lack the aggressive spines of some species.

The variety angustifolia has long, narrow leaves and small, abundant berries. I. cassine var. myrtifolia has petite leaves and fruit. Some cultivars have yellow berries and dark green leaves.

Walmart carries three, 10, or 20 live plants ideal for those who want to create a hedge screen.

While it’s not the most common species out there, it’s worth seeking out.

Finetooth Holly

You probably won’t see finetooth holly (I. serrata) in gardens too often, and that’s a shame.

It’s cold hardy, with glossy, serrated leaves that add texture to the garden. Even without a male plant, it produces bright red berries in the fall.

I. serrata is also known as Japanese winterberry because they closely resemble winterberry (I. verticillata) except with smaller berries and leaves.

The berries tend to persist on the plant much later than most other common Ilex species. It’s hardy in Zones 5 to 9.

Foster’s Holly

Topal or Foster’s holly (I. x attenuata) is a naturally-occurring hybrid between dahoon and American holly that grows in Zones 6 to 9.

The result is something in between the two, with glossy, dark olive-green leaves and persistent red drupes.

While the leaves do have spines on the edges, they are small and widely spaced.

‘Longwood Gold’ has bright yellow drupes. ‘Fosteri’ has extremely abundant fruit and is more cold hardy than the standard hybrid, growing down to Zone 5.

It’s available at Nature Hills Nursery in a #2 container.

Inkberry Holly

Native to east and central North America, inkberry (I. glabra) gets its name from the ink-black berries that grow on the plant in the fall.

There are also white-berried cultivars, though, so watch for those if you prefer a white hue.

Most are hardy in Zones 5 to 9, though a few, like nordic inkberry (I. glabra ‘Chamzin’) are good down to Zone 3.

This female cultivar flowers and fruits reliably, with a male, of course, and the birds love the persistent berries.

Even when the fruits aren’t present, the four-by-four-foot shrub adds garden interest with its glossy oval leaves that lack any sharp spines.

Nature Hills carries this option if you’re interested (and who wouldn’t be?).

If you’re looking for an alternative to the standard boxwood, ‘Gem Box’ is a petite inkberry that stays under four feet tall and wide.

In the spring, the leaves have pinkish-red tips, followed by black berries in the fall.

It is an extremely dense grower that stays under four feet tall and wide. It’s all the holly beauty in a contained package.

Grab a live plant at Fast Growing Trees.

Learn top tips for growing inkberry holly in our guide.

Japanese Holly

Japanese holly (I. crenata) doesn’t have the spiny leaves, so these plants work well in spaces where you might bump up against them.

The small leaves may be solid or variegated and come in colors like gray-green, deep green, or a blend of green with yellow, white, or cream. You can learn more about the different types of Japanese holly in our guide.

They grow almost anywhere in Zones 5 to 9, so long as it isn’t too hot and humid or super dry. If you need a crawling cultivar, ‘Kufujin,’ with its variegated foliage, is an exceptional option.

‘Soft Touch’ is a particularly nice choice because its foliage is downright soft and the plant matures to just three feet tall and wide.

Fast Growing Trees carries this option in quart, one-, two-, or three-gallon pots.

Learn more about growing Japanese holly here.

Lusterleaf Holly

I. latifolia, commonly called the lusterleaf holly, isn’t well known, and in my opinion that needs to change.

This Japanese native grows in Zones 7 to 9 and up to 20 feet tall in partial shade to full sun, and moist to dry soil.

But what makes it so fantastic are the massive leathery leaves. Each individual leaf can be up to eight inches long and four inches wide, making them some of the largest in the genus.

Along with the bright red drupes, it makes for an eye-catching specimen or hedge in the garden.

There are many attractive cultivars out there, including ‘Agena’ and ‘Venus,’ and I. latifolia is used to create hybrids with other Ilex species.

Oak Leaf Holly

Oak leaf holly (I. x ‘Conaf’) is a hybrid cultivar of I. x ‘Mary Nell,’ part of the Red Holly™ series hybridized by breeder Jack Magee at Evergreen Nurseries in Mississippi.

The plant gets its name from the foliage that, if you squint, looks a bit like an oak leaf. The leaves emerge as bronze in the spring and turn deep green as they mature.

One of the characteristics people love about this plant is that it’s self-fertile, so you will see the greenish-white blossoms and orange-red berries even if you only have one specimen.

It takes on a beautiful pyramidal shape naturally and grows well in Zones 6 to 9.

Bring one home from Nature Hills Nursery in a #3 or #7 container.

Once you’ve placed your order, visit our guide to growing oak leaf holly to learn all about its history and care.

Possumhaw Holly

Possumhaw or meadow holly (I. decidua) is a North American native, hardy in Zones 5 to 9, and one of the deciduous species, so you’ll have red berries on bare branches throughout the winter. Birds, possums, and raccoons love them.

This small tree can grow up to 30 feet tall, but it typically stays smaller. The dark green leaves lack spines and turn yellow in the fall.

Round Leaf Holly

This beautiful Asian evergreen grows in sunny areas on hillsides and goes by the name round leaf or Kurogane holly (I. rotunda).

It’s a small tree or large shrub, though there are many cultivars in different sizes.

It gets its name from the round-oval leaves and is hugely popular in Japan but harder to find in the US.

If you live in Zones 6 to 9, you can enjoy this spineless sun-lover and its large clusters of small red berries.

Don’t confuse this plant with round leaf Japanese holly (I. crenata ‘Latifolia’). They have a similar look but different growing requirements.

Winterberry Holly

Native to the eastern United States, including chilly areas in Zones 3 to 9, winterberry (I. verticillata) is a medium-sized deciduous shrub that handles soggy soils with no problem.

True to its name, the yellow, red, or orange berries persist from fall and through the winter until the wildlife gobbles them up.

Happy in full sun to part shade, it tops out at about 15 feet tall and wide, but it will send out suckers and gradually spread even further.

The oval leaves are spineless and the colorful berries appear at the end of the branches, making them more prominent than some species.

Little Goblin® (I. verticillata ‘VCIV2’) is a compact option at just four feet tall and wide with bright orange berries and vibrant green foliage. Grab one in a #3 container from Nature Hills.

We have lots of information about growing winterberry holly in our guide. Check it out.

Yaupon Holly

Native to the southeastern parts of the United States, yaupon holly (I. vomitoria) is a gorgeous evergreen that can be grown as a large shrub or small tree, with dark green, oval leaves with toothed margins. In the fall, there are bright red berries that stick around through late winter.

It loves moist soil but can tolerate some dryness and will thrive in some shade or full sun, making it a versatile garden option. It’s also a valued source of caffeine for indigenous people.

‘Schillings’ is a dwarf cultivar that stays just six feet tall and wide.

Head to Home Depot to pick up ‘Schillings’ plants in three-gallon pots.

You can learn more about yaupon holly in our growing guide.

Managing Pests and Disease

Pests and hungry herbivores are going to be the biggest threat to your plants, but if you have heavy clay or you tend to overwater, you might run into root rot. Let’s look at herbivore threats first.

Herbivores

You’d think that a spiky plant would be safe from herbivores, but you’d be wrong. Both deer and rabbits will munch on them.

Deer

When I first started planning my garden at our cabin in a deer prone area, I talked to the local nursery about which plants deer would avoid.

They recommended things with spikes and prickles, so I thought hollies would be sure-fire options.

Imagine my dismay when I watched as those fearless deer nibbled on my holly shrubs, and they didn’t even avoid the spiky leaves in favor of the softer leaves higher up!

All that is to say that hungry deer certainly won’t pass up a holly snack.

If you deal with deer already, you probably know the routine. Protect young plants with fences or cages and use your favorite repellants.

If you’re new to the joy of gardening with ungulates, visit our guide for some tips.

Rabbits

It’s not their favorite meal, but rabbits will eat holly, especially the bark and berries. They’ll even go for the leaves, especially on those species that lack spines.

Pests

I’ve never been tempted to take a bite of a holly before, but then again, I’m not a plant-eating pest. Apparently it’s delicious or nutritious because there are several pests that feed on hollies.

Leaf Miners

Leaf miners (Phytomyza spp.) are the larvae of small black flies that chew tunnels through the inner layers of the leaves of many different garden plants.

When they’re present, you will see squiggly thick yellow lines through the leaves. It can be ugly and might weaken the plant.

You can spray for leaf miners, but keep in mind that it will take repeated treatments. Once the larvae are inside the leaves, sprays won’t reach them, so you need to spray to kill the adults.

Any spinosad-based spray will work. Apply it every two weeks at the first sign of leaf miners and keep spraying for at least two months.

The life cycle of a leaf miner is just two weeks and there can be up to ten generations per year.

Bonide makes a killer product called Captain Jack’s Deadbug Brew, which is available at Arbico Organics in 32-ounce ready-to-use, concentrate, or hose-end, and 16-ounce concentrate.

You can learn more about how to manage leaf miners in our guide.

Mites

Red mites are closely related to ticks and spiders, and though they are tiny, they can cause serious harm to your hollies.

Southern red mites (Oligonychus ilicis) are the most common, but there are several species in the Tetranychidae family that will feed on hollies.

These pests use their sucking mouthparts to draw the sap out of the plants, spreading disease and draining plants’ energy. They tend to focus their efforts on the undersides of leaves and the joints where the leaves meet the stems and they’re most active during spring and fall.

When they’re feeding, the plants will be stunted and the leaves might take on a bronze hue.

Mites are present in every garden, so finding them is not necessarily a sign that something is wrong. The problem is when they become overabundant.

Typically, natural predators like ladybugs, predatory mites, and lacewings will keep them under control, but if the balance in your garden is off, the spider mite population can grow out of control and that can spell disaster for young or small plants.

The easiest way to deal with spider mites is to blast them off your plants with a steady stream of water once a week.

You can also introduce natural predators such as green lacewings. These beneficial insects eat all kinds of bad bugs, so they’re definitely something you want around.

You can buy them in various quantities from Arbico Organics to add some to your garden.

Nematodes

I won’t sugarcoat it, nematodes can be difficult to diagnose unless you send in a sample to your local extension office for testing. That’s because the symptoms are extremely generic.

Your plant might be a little stunted or maybe some of the leaves will turn yellow and drop to the ground.

There are several nematode species that might infect your plants, including root-knot (Meloidogyne spp.), ring (Criconemoides spp.), stunt (Tylenchorhynchus spp.), sting (Belonolaimus spp.), and spiral (Helicotylenchus spp.) nematodes.

If you can confirm that your plant is infected, the only option is to dig up the plant and dispose of it. There is no treatment option.

Scale

Scale insects feed on many different species, including those in the Ilex genus. Chinese holly is especially susceptible.

These pests are small, flat, and covered in a waxy coating that might be white or gray. They use their sucking mouthparts to feed on the sap of the plants, resulting in yellowing leaves and stunted growth.

There are lots of options for control, including sprays and mechanical removal. Check out our guide to scale for more details.

Disease

Hollies are mostly disease free. But if they are overwatered or growing in poorly draining soil, root rot is a possibility.

There are two pathogens that can make the roots of a holly plant turn black and mushy, rotting away until the plant dies. The first is the fungus Thielaviopsis basicola and the second is the oomycete Phytophthora cinnamomi.

Both thrive in moist soil and both cause the roots to become black and soft. Aboveground, the leaves will wilt, growth will be stunted, and the foliage might turn yellow and drop from the plant.

Ensuring good drainage can help, as can being careful not to overwater, but both pathogens can persist in the soil for years and can easily travel in water, so it’s hard to avoid altogether.

Japanese hollies (I. crenata) are extremely susceptible because they can’t tolerate poor drainage at all. If you have heavy clay with poor drainage, don’t even think about growing a Japanese type.

Chinese (I. cornuta), yaupon (I. vomitoria), and American holly (I. opaca) are all somewhat resistant.

If your plant is infected, you can do your best to support it with appropriate food and water, but you’ll eventually need to pull it and dispose of it.

Best Uses for Holly

Depending on the species, hollies can be stately trees or large shrub specimens.

There are some that stay compact at just a few feet tall, or those larger varieties that work as hedges or living fences. There are even some creeping or ground cover options.

It might not be the first plant you think of for bonsai, but many species make extremely pretty bonsai specimens.

Plant your hollies with shade-loving flowers like impatiens, begonia, hosta, bleeding hearts, or pansies.

I like to grow them with early bloomers like azaleas or rhododendrons, camellias, hydrangeas, or heath to add some color when hollies are lacking flowers or berries.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Broadleaf evergreen | Flower/Foliage Color: | Green, cream, white/Green, cream, yellow |

| Native to: | North America, Europe, Asia, Africa | Tolerance: | Soggy soil, some drought, deep cold, heavy pruning |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 3-11 depending on species | Water Needs: | Moderate-high |

| Season: | Spring-summer bloom, fall-winter berries | Soil Type: | Sandy to loamy |

| Exposure: | Full shade to full sun, depending on species | Soil pH: | 3.5-7.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | Up to 10 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 2-20 feet, depending on species | Attracts: | Birds, bees, butterflies, herbivores |

| Planting Depth: | 1 inch (seeds), same depth as growing container (transplants) | Companion Planting: | Azaleas, begonia, bleeding hearts, camellias, heath, hydrangea, impatiens, hosta, pansies, rhododendrons |

| Height: | Up to 80 feet | Uses: | Tree, specimen, hedge, living fence, ground cover, bonsai |

| Spread: | Up to 30 feet | Order: | Aquifoliales |

| Maintenance: | Low | Family: | Aquifoliaceae |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate | Genus: | Ilex |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Deer, rabbits; Leaf miners, mites, nematodes, scale; Root rot | Species: | Aquifolium, cassine, coriacea, cornuta, crenata, decidua, glabra, kaushue, latifolia, montana, opaca, paraguariensis, rotunda, rugosa, serrata, verticillata, vomitoria |

Let’s Hear It for Hollies!

For a genus with dozens of popular and reliable species, you can’t do better than Ilex.

There are piles of deciduous and evergreen options in sizes from itty-bitty to towering tall, with or without spikes, and with or without colorful berries.

Are you growing holly? Which species do you fancy? Share your plans with us in the comments section below.

Did this guide help you figure out how to grow hollies and which will work for your space? I hope so.

If so, we have a few other guides to evergreen shrubs that might be useful. Check these out next: