Ilex crenata

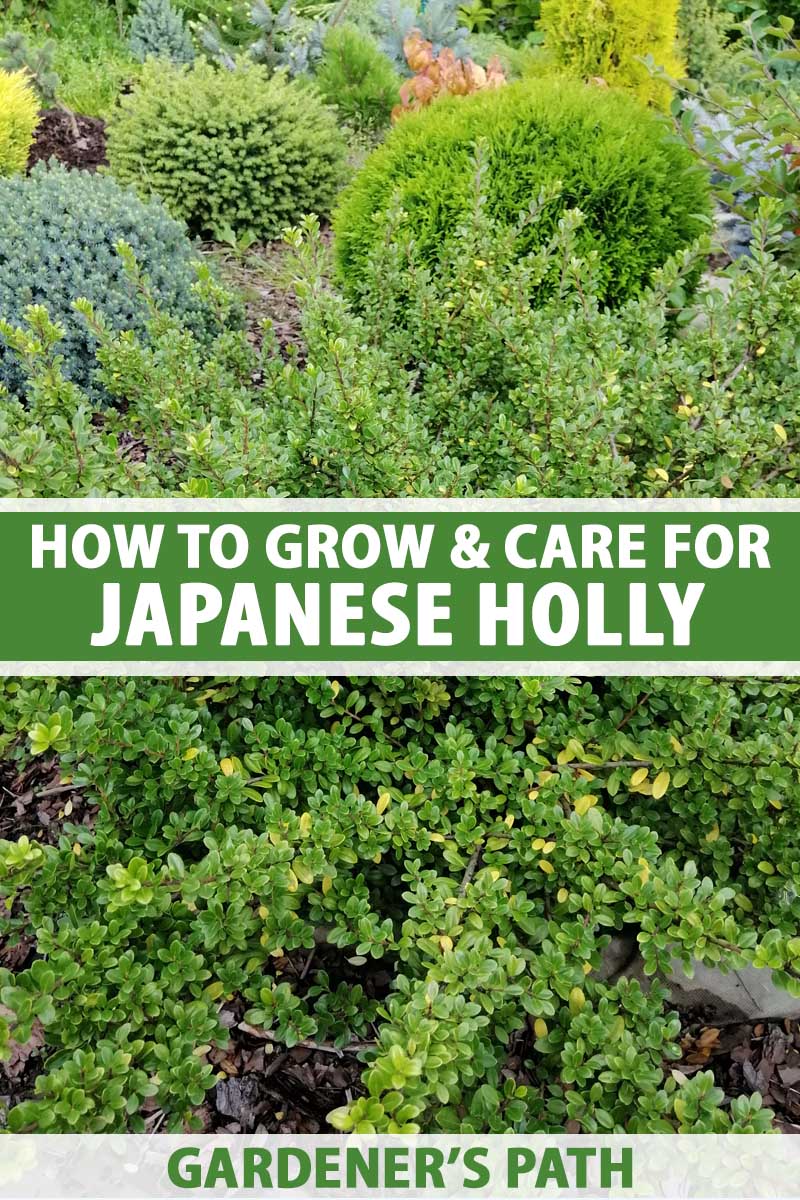

Dealing with a difficult area in the garden? I’ve been there.

I once had a group of Japanese hollies growing next to my patio and I made the very stupid, no-good decision to pull them out to plant something with showier flowers.

Nothing I planted in that spot ever did well, and believe me, I tried a lot of plants. The soil was clay and the light exposure wasn’t ideal. Plus, I missed the winter color the evergreens provided.

You live and you learn (or just learn from my mistakes).

Since then, whenever I need to fill a challenging spot, one of the first plants I turn to is Japanese holly.

Unlike other plants in the Ilex genus, these beauties don’t have spiny leaves, so you can place them in areas where you might brush up against them without coming away scratched and scarred.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

These evergreens come in solid or variegated cultivars and with foliage that can range from pale gray-green to deep, dark green, and some with yellow or cream accents.

Sound like something you’d like to add to your garden? Here’s what we’ll go over in the following guide so you can be sure yours will thrive:

What You’ll Learn

Did I forget to mention that these shrubs are rarely bothered by pests or diseases? Troubled by deer or rabbits? Not Japanese holly.

Can you tell I’m a fan? You will be too, so let’s dig in.

Cultivation and History

Native to Japan and other parts of East Asia, this species thrives in moist woodland and mountain areas in full or part sun.

It prefers acidic soil but it’s fairly tolerant of a range of soil conditions and pH levels. If you struggle to find plants that can survive in your heavy clay soil, Japanese holly might just be the thing.

That doesn’t mean it needs heavy, wet soil, though. It can be equally as happy in dry soil, and it can even survive in the shade.

It seems like just about the only thing these glossy beauties can’t tolerate is prolonged drought, or high humidity combined with heat as you might find in the American south. They do well in USDA Hardiness Zones 5 to 9.

Japanese hollies are dioecious, which means the plants are either male or female. If you want to grow berries and harvest seeds, make sure you plant one of each sex for best results.

Males don’t produce berries, so if you want to avoid them, pick a male plant. Don’t worry, though, the berries are small and don’t make a mess. Birds usually pluck them off the plants before they can fall to the ground anyway.

The typically white blossoms form in mid- to late spring, and the shiny black seeds inside the fruit produced by pollinated female flowers ripen in the fall.

This plant is often confused with dwarf cultivars of yaupon holly (I. vomitoria), and though they look similar, they are different species.

Japanese hollies typically grow about 10 feet tall and five feet or so wide, but there are many cultivars out there that have different sizes and shapes. Speaking of, there are a lot of different cultivars of this species – over 500, at last count!

The species plant was first brought to the US in 1898, and it has become a favorite in gardens across the country.

Propagation

Japanese hollies can be grown from seed, stem cuttings, and seedlings or transplants.

Propagating seeds is the least reliable method, with germination rates somewhere just above 50 percent. There’s also no way for home growers to tell whether they’ve produced male or female plants from seed until they mature enough to flower.

From Seed

You can purchase seeds or harvest them from ripe berries. Just be aware that hybrids won’t grow true to type. That doesn’t mean you won’t have a beautiful bush, just that it might not have the characteristics like leaf color or size that you were expecting.

The seeds must be cold stratified. That means either planting the seed in the fall and allowing Mother Nature to take care of the job for you, or recreating the same conditions in your home.

This involves filling a resealable container or bag with sphagnum moss or sand, moistening the medium, and placing the seeds inside.

Place the container in the refrigerator for 12 weeks, checking once a week or so to make sure the medium is still moist. The seeds should germinate by this time. Any that haven’t should be tossed out.

Place the germinated seeds outdoors in the spring after the last projected frost date for your area. Ungerminated seeds that you won’t be stratifying indoors should be placed in the ground in late fall.

Seeds should be buried a quarter-inch deep in the earth. Ideally, work some compost into the soil to improve drainage and increase water retention.

Japanese hollies prefer well-draining soil that is loose, moist, and slightly acidic with a pH of 4.5 to 6.5. But as we mentioned, they can survive in anything ranging from sand to clay.

To save your own seeds from existing plants, collect the berries in late fall. They should be plump and have some give. Cut them in half, scrape out the seeds from the interior, and rinse them in a bowl filled with water.

Allow them to dry on a paper towel then treat them as described above. Remember, you must have a male and female plant to produce fertile seeds.

From Cuttings

Stem cuttings are more reliable and quicker to propagate than seeds. The process is fairly simple, too.

To begin, remember that cuttings are clones of the parent plant, with the same DNA. Female plants that are cloned via stem cutting propagation will yield female clones, and taking cuttings from male plants results in male clones.

In the late summer, take a six-inch cutting from new growth – it will be green, rather than hard and brown. Use a clean pair of secateurs and make the cut at a slight angle.

Strip the leaves off of the bottom half of the cutting and dip the cut end a rooting hormone product like Bonide’s Bontone II Rooting Powder, which Arbico Organics carries in 1.25-ounce containers.

Bonide Bontone II Rooting Powder

Fill a four-inch container with a potting medium and work in a little acidic fertilizer. I like to use compostable containers like CowPots, but anything that’s the right size works.

Add a teaspoon of the mix to each container and work it into the soil well – I recommend my favorite type in the How to Grow section below, so keep reading!

Stick the cutting into the soil so that about two inches of the stem is positioned below the soil line. Water the soil well and keep it consistently moist but not wet.

After about six weeks, your cuttings should have some good roots forming underneath the surface of the soil. Give your cutting a little tug. If it resists, you’re in good shape.

Now you can transplant out into the garden as described below.

From Seedlings and Transplanting

You can find seedlings or small potted specimens at practically any nursery, and many big home stores. If you want quick results, this is the way to go.

If you started your own from seed, remember that you won’t be able to tell if they’re males or females until they’ve begun to flower.

To plant them, the first step is to prep the area. It never hurts to work a little compost into the soil. Doing so improves both drainage and water retention.

If you have sandy or clay soil, you might want to work an equal part of compost in with the existing soil. Dig down about two feet and out three feet as you mix and cultivate the soil.

Japanese hollies have fairly shallow, fibrous roots, as well as a main taproot that doesn’t grow too deep unless you have dry soil.

Fill the hole you dug back up completely, and then excavate a hole that’s twice the width of the container the plant is growing in.

Gently remove the plant from its container (unless you rooted cuttings or grew seeds in compostable pots) and loosen up the roots as much as possible. Lower the plant into the earth and fill in around the roots with soil.

Water well. For the first year, keep a close eye on the soil moisture level – you want it to stay moist. Don’t let more than the top inch of soil dry out in between watering.

How to Grow Japanese Holly Shrubs

Japanese hollies can tolerate short periods of drought when they are mature, but don’t let them dry out when they are young and are still becoming established.

Plants growing in full sun need more water than those in shadier spots.

When they are young, don’t let more than the top inch of soil dry out between watering. Once they’ve become established, the top two inches can dry out before you water again.

If the leaves begin to turn yellow on your plant, test your soil’s pH. Alkaline soil can cause the leaves to turn yellow. Remember, acidic soil is the ideal preferred by Japanese holly, with a pH of 4.5 to 6.5.

Neutral soil with a pH of 7.0 is also okay, but anything much above that and the foliage will likely begin to change color.

Fertilize in the early spring just as new growth is starting to emerge. A balanced fertilizer or an acid-lover’s mix is all you need. Don’t bother with foliar or extended fertilizers – a good old granular option works perfectly well.

Down to Earth Acid Mix Fertilizer

Down to Earth has an excellent formula for acid-loving plants. Arbico Organics carries it in one- or five-pound biodegradable boxes.

Apply granular fertilizer a few inches outside of the drip line according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, and water it in well.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full sun or partial shade.

- Work compost into the soil to improve drainage and water retention.

- Keep the soil moist as the plants become established.

- Fertilize once in early spring.

Pruning and Maintenance

Japanese holly is a slow-growing shrub. It also tends to grow with a dense, tidy shape without any help from you, the gardener. That means you won’t need to worry much about pruning.

Beyond removing any dead or diseased wood, or giving the plant a little shaping if you desire, you really don’t need to do much.

That said, you can go entirely in the other direction and do some regular heavy pruning if you like. Because of its dense growth and tolerance for heavy pruning, this plant makes an ideal specimen for topiary.

Since there are so many growth habits to choose from among the available cultivars, including narrow and upright or short and wide options, you’re only limited by your imagination.

If you do decide to prune, this work should be done in the late winter or early spring. New growth forms on soft green wood, while older growth is the brown wood. You want to prune before new growth begins to form.

Having said that, you can prune at just about any time of year and the plant won’t suffer. It just fills back in more quickly if you prune early in the year. Don’t prune in the late fall, to avoid tip burn.

To prune your Japanese holly, use pruners or secateurs to cut an individual branch next to a leaf node. You can also use hedge trimmers to shear the plant into the desired shape.

In traditional Japanese gardens, these plants are often pruned so that the lower trunk is exposed to show off the shrub’s architecture. These shrubs are also often pruned into the tamamono and karikomi styles.

Tamamono is a semi-rounded shape that is twice as wide as it is tall. This makes a lovely contrast to the upright form of many trees.

Karikomi isn’t a shape but rather, the practice of shearing a plant’s branches uniformly so it almost appears smooth. O-karikomi is a term used to refer to a grouping of shrubs in this style.

If you need to rejuvenate an older or scraggly-looking plant, you can do more drastic pruning. To do this, cut the entire shrub back to about a foot above the ground and allow new foliage to grow for a year before pruning again.

Cultivars to Select

Some species are famous for the original species plant, but the opposite is true with Japanese holly.

You will only rarely find the parent species available at nurseries and garden centers. There are many hybrids and cultivars, and these are what you’ll usually come across for purchase.

Some grow as tall as 15 feet, while others stay extremely small.

‘Compacta,’ for instance, stays under five feet tall and wide. It maintains a compact, mounded shape without regular pruning.

Nature Hills Nursery carries this popular cultivar in a #3 container.

On the other end of the spectrum, ‘Sky Pencil’ grows up to eight feet tall and just 18 inches wide with a dense, columnar growth habit, making it perfect grouped together to make a hedge or as a pair flanking an entrance.

Home Depot has ‘Sky Pencil’ in gallon containers.

‘Hoogendorn’ can act as a tall groundcover, topping out at about 24 inches tall and stretching three feet wide. It has such a thick, dense growth that weeds have a difficult time punching through.

The only weeding I ever had to do around my ‘Hoogendorn’ was to pull the occasional errant blade of grass that found a way through.

If that sounds like something you need in your yard, head to Nature Hills Nursery to pick one up in a #3 container.

Want More Options?

There are hundreds more cultivars to choose from, so if you’d like to learn a bit more about them, you might be interested in our guide to Japanese holly cultivars.

Managing Pests and Disease

If you’ve ever asked yourself if there’s a plant out there that you can just put in the ground without having to stress about it being killed by pests or diseases, prepare to be excited.

Japanese hollies aren’t bothered by herbivores, and very few invertebrates will take a bite. As for disease? It’s practically unheard of.

Insects

Look, ma! No aphids!

There are lots of reasons to love Japanese hollies, but I’d be lying if I said that not having to worry about aphids didn’t factor into my purchasing decision. There’s only one pest to watch for, and it’s pretty easily dealt with.

Spider Mites

One of the rare insects that trouble Japanese holly, two-spotted spider mites (Tetranychus urticae) and southern red mites (Oligonychus ilicis) form masses of fine webs over the foliage – but that’s not what you need to worry about.

These oval-shaped yellow or red insects feed on the plant, resulting in bronzing, stippling, and in the worst-case scenario, leaf drop.

The first step to deal with the problem is to encourage or bring home predatory insects. Think ladybugs, lacewings, and assassin bugs. Any one of these will work hard in your yard to keep the bad bugs at bay.

If you don’t have them naturally, grab a container of 250, 500, 1,000, 2,000, or 5,000 Zelus renardii assassin bug eggs at Arbico Organics.

Next, buy yourself some insecticidal soap if you don’t already have some. Spray the plant thoroughly, from top to bottom, once a week to kill the mites. It might take a month or more to eradicate them.

Once again, our friends at Arbico Organics can help to fill your garden toolkit. They carry Bonide’s insecticidal soap in 12 or 32-ounce ready-to-use bottles.

You can learn more about eradicating spider mites in our guide.

Disease

You won’t see your various mildews or leaf spots on Japanese hollies, but they are susceptible to root rot.

Though the plants can tolerate heavy soil, planting in it does increase the risk. There are two types in particular to watch for.

Black Root Rot

Black root rot is a fungal disease caused by the pathogen Thielaviopsis basicola. When the fungus attacks a plant, the result is slowed or stunted growth. You may also see yellowing leaves.

The real damage is happening underground, however, where the roots are turning black and mushy.

If your plant seems to droop during warm weather and then perks back up, no matter how much or how little water it has, this might be the cause. You can be fairly certain if you see any of the other symptoms mentioned above.

It’s not an extremely common disease, but that doesn’t mean it never occurs, since Japanese hollies are susceptible – ‘Hoogendorn,’ ‘Nigra,’ ‘Green Cushion,’ ‘Mobjack Supreme,’ ‘Hetzii,’ and ‘Helleri’ in particular.

The fungal pathogen can live in the soil for years, so if you’ve ever had this disease turn up in your garden, don’t plant a holly in that spot. If your plant contracts black root rot, you’ll need to pull it and dispose of it.

Phytophthora Root Rot

Another root rot, this one caused by the oomycete Phytophthora cinnamomi.

It is more common in areas with soil that drains poorly, because the pathogen needs lots of moisture to survive. Again, you will see stunted growth and yellowing leaves while the roots underground turn mushy and black.

There is no cure, so pull any plants that are infected and dispose of them.

Best Uses for Japanese Holly Bushes

Japanese holly is a versatile option. It can be used as a screen, in mass plantings, and the aforementioned topiary.

It can also be planted as a tall ground cover, in mixed beds, along foundations or fences, or as a specimen for bonsai.

When making your selections, be sure to pick a cultivar that has a habit that’s suited to its intended use.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Woody evergreen shrub | Flower/Foliage Color: | White/green, yellow, cream |

| Native to: | Eastern Asia | Tolerance: | Clay, minor drought |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 5-9 | Soil Type: | Loose, loamy |

| Season: | Spring (insignificant), fall-winter (berries) | Soil pH: | 4.5-6.5 |

| Exposure: | Full sun to part shade | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Time to Maturity: | 10 years | Maintenance: | Low |

| Spacing: | Depends on cultivar | Attracts: | Bees, birds |

| Planting Depth: | 1/4 inch (seeds), same depth as original container (transplants) | Companion Planting: | Azalea, Japanese maple, rhododendron |

| Height: | Up to 15 feet | Avoid Planting With: | Barberry, cotoneaster, forsythia, juniper |

| Spread: | Up to 10 feet | Uses: | Bonsai, groundcover, foundations or fences, mass planting, screen, topiary |

| Growth Rate: | Slow | Family: | Aquifoliaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Ilex |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Spider mites; black root rot, Phytophthora root rot | Species: | Crenata |

Japanese Hollies Are Fabulously Fuss-Free

Whether you need a humble background plant or a stunning topiary focal point, Japanese hollies can do it all.

Plus, they do it without being fussy or demanding. You don’t have to worry about deer or aphids making a meal of your shrubs, and they look like you spent hours pruning even when you haven’t pulled out the clippers in years.

Which cultivar are you growing? Let us know in the comments below – we love to share the Japanese holly love.

If you want to learn more about the wonderful world of hollies, you might enjoy some of our other guides, which include:

The comment about the mildew is wrong. I purchased 3 japanese hollies from a local nursery and every one of them has had awful powdery mildew from the first week. It’s been impossible to combat.

Hi Devin, that’s a shame; I’m sorry you’re experiencing that. Japanese hollies rarely experience mildew, but never say never. Plants raised in a greenhouse can be more susceptible, and my guess is that your plants came from a grower that is having a mildew outbreak. Maybe our guide to powdery mildew can help you get things under control.

Small, young Japanese multi-colored was not watered as it needed. Several dead branches & leaves. Trimmed it, watered, need info on how to bring the plant back to health.

Hello there, it sounds like you are on the right track. You should trim off or remove any dead areas and give it plenty of water on the day you prune. Then, maintain an appropriate watering schedule for your area going forward and the plant should recover in time.