Larix spp.

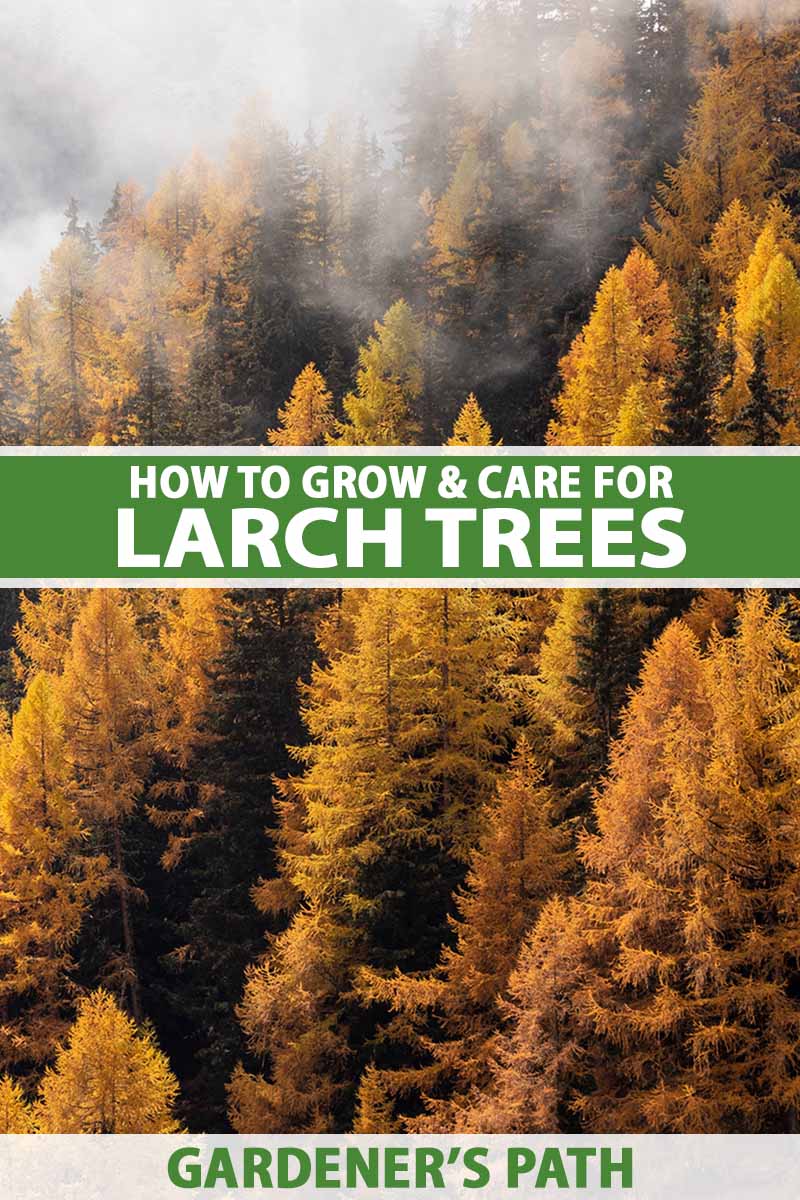

A larch is a pretty dramatic sight to behold. The trees are ramrod straight and covered in bright green, inch-long needles that shift to golden yellow in the fall.

They’ve adapted to extreme conditions, perching on rocky outcroppings at extreme elevations in North America, adding color to barren landscapes where no other tree species can grow.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

The first time I saw a wild larch, I was hiking in the mountains in Washington. To be honest, I thought they were dying. At the time, I didn’t know deciduous conifers existed.

The golden yellow trees were beautiful, backlit by the sun. But I assumed the forest was being devastated by some beetle or something. Why else would those “evergreens” be turning yellow?

Okay, now I know better, and I can appreciate the beautiful fall color without worrying about the widespread decimation of North American forests.

These conifers actually evolved to drop their leaves because of their extreme native range. They grow at the highest northern latitudes and the highest elevations of any tree in North America.

In these locations, it’s too cold to photosynthesize in the winter, so there’s no point in hanging onto those leaves.

Foliage has a high nutrition requirement, and it’s too costly to have around if it isn’t doing its job. Since they can’t photosynthesize anyway, they toss off those leaves.

Lucky us! We get to enjoy the show.

If you want to bring the performance to your own space, you’ll need to learn about planting and raising larches. This guide aims to help with that! Here’s what we’ll go over:

What You’ll Learn

Sound good? Let’s get going!

What Are Larches?

Larches are trees in the genus Larix. The genus name doesn’t have some exciting symbolism behind it, it’s simply the classical Latin name for the tree. But the trees themselves are pretty dang cool.

Trees in this genus are deciduous pines in the Pinaceae family. In fact, larches are the only deciduous conifers in western North America.

The young bark is silvery or gray-brown before shifting to a reddish brown as the plants mature.

When the cones emerge, they’re bright, vibrant red or violet, gradually maturing to green and then brown. They can be quite beautiful and add flower-like color to the landscape.

It can be hard to tell all the various conifers apart, so let’s take a quick look at how larches differ from other pines.

One clue is that the needle-like leaves are clustered in groups of 10 or more. Pines typically have clusters of two to five needles, but they might have up to 10.

The cones of these monoecious plants, of which there are male and female types, are held upright on the branches, while many pines have cones that face down.

But the easiest way to tell them apart from other conifers, other than being bare in the winter, is to wait until the spring to see the fuzzy needles emerging on the bare branches.

The current year’s twigs will be wooly on the subalpine species, but eastern and western larches aren’t wooly.

Larches are survivors. You can find them growing at the tree line in high elevations, clinging to rock faces. They’re the ones that survive in the northernmost latitudes, up to the Arctic. No other tree grows further north than they do.

That means even gardeners in the coldest USDA Hardiness Zones, from 1b through 8a, can find a larch for their area.

These trees can also survive fires that decimate other species. Where wildfires are frequent, larches and the closely-related lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) dominate the scene. Some are over 900 years old, with trunks scarred by decades of fires.

You’re probably wondering what on earth can stop them, right? They’re super tough! But their weakness is shade.

While the lumber of larches is valuable, many of the oldest specimens dodged logging because the trees tend to develop ring shake and bole rot as they age.

This rot means they’re prized by woodpeckers and other birds that nest in trees, but less useful for loggers.

They’re home to the Columbia silkmoth (Hyalophora columbia), which is also known as the larch silkmoth because these beautiful reddish-brown insects lay their eggs at the base of the needles.

Larches are also home to the eye-spotted bud moth (Spilonota ocellana), the poecila sphinx (Sphinx poecila), the northern pine sphinx (Lapara bombycoides), the apple sphinx (S. gordius), and the pine measuring worm (Hypagyrtis piniata).

Some people consider the larch’s attractiveness to moths to be a good thing, but others, like organic apple growers, aren’t such fans.

That’s because larvae like that of the eye-spotted bud moth feed on the skin of fruits and eat the leaves of apple trees.

Organic farmers use pheromone traps to draw in and eliminate devastating codling moths, leaving the trees open to invasion by species that aren’t attracted to the traps once the codling moths are gone.

If you’re growing organic apples and using pheromone traps, don’t plant larches near your orchard unless you’re willing to accept some cosmetic damage to your fruits.

Grouse (family Phasianidae) eat the needles and buds, but they don’t do any serious damage to the plants.

Cultivation and History

There are five commonly grown species in North America.

These are eastern (L. americana), European (L. decidua), tamarack (L. laricina), subalpine (L. lyallii), and western larch (L. occidentalis).

Trees within the genus will hybridize with each other where their ranges overlap.

Siberian larch (L. sibirica) grows in Russia, Chinese (L. potannii) in China, and Japanese (L. kaempferi) in Japan.

The Russian and Chinese species are commonly cultivated in their native regions, but they aren’t often found outside of the area. The Japanese species can be found at North American nurseries that specialize in rare plants.

The western species are the largest larches in the world and can grow nearly 200 feet tall with a triangular growth habit.

On the smaller end of things are the subalpine and tamarack larches, which grow only to about half the height of their western counterparts.

Compared to many conifers, that’s downright tiny, but consider their growing range. They’re usually the tallest trees around nonetheless, because other species can’t tolerate the harsh conditions larches thrive in, so it’s all relative.

Tamaracks top out at about 80 feet but they usually stay smaller. The pretty maroon cones are the smallest of any larch at just half an inch long.

Tamaracks are also referred to as eastern larches, but that’s a bit of a misnomer since you can find them everywhere from Alaska to eastern Canada.

There have been numerous attempts to cultivate the L. lyallii, but none have succeeded so far.

If you want to enjoy the beautiful yellow-green leaves of this tree, you’ll need to do some hiking in Montana, Oregon, Idaho, or Washington.

L. occidentalis, on the other hand, can be found cultivated all over the place in the western US, from parks to suburban backyards.

Across the US, the European species is the most popular in home gardens. I don’t know why, since they’re less adapted to our environment, and we have so many marvelous native options.

Maybe it’s the large cones? They’re twice the size of most North American species. Or maybe it’s just that they’ve been cultivated longer than North American species, so there is more variety to choose from.

The gum, bark, foliage, and cones were used by tribes as varied as the Micmac, Abnaki, Algonquin, Chippewa, Cree, Iroquois, Malecite, Nez Perce, Okanagan, Ojibwa, and Potawatomi as a treatment for everything from colds and coughs to arthritis, frostbite, and anemia.

Various parts were also widely used as a laxative, so let that be an indicator of what this plant does if you consume it.

The roots were fashioned into strips to bind wood together to make canoes, and the Salish and Kutenai would hollow out a cavity in the trunk and allow the sap to accumulate.

Once enough did, they would harvest it, allow it to concentrate through evaporation, and consume it as a sweetener.

Today, we still use the water-soluble gum called arabinogalactan in pharmaceuticals, ink, and paint.

Larch Tree Propagation

Larches are extremely easy to propagate from seed, and the seeds have a high germination rate. They just take a long time to germinate.

Cuttings are a little less reliable, but another good option. And of course, you could buy yourself a nice little specimen for transplanting at a local nursery. They might even have some fun options that grow particularly well in your area.

From Seed

Starting plants from seed is a labor of love and it’s not ideal if you’re in a rush to add a larch to your yard. But if you’re curious about how to do it, here’s the process:

First, harvest the large, mature, open, brown cones. Crack and peel apart the scales close to the base and look for the seeds. They’re tan and usually have a little wing attached to help them fly away from the tree.

Examine the seed husks before you plant them, since they can sometimes be empty. You don’t want to waste time and effort on an empty seed husk.

Cones that are only partially open tend to contain the best seeds since they escape once the cones open fully. And don’t bother looking for cones on the ground. Larches hold onto their cones for up to a decade, so the best place to find them is on the tree.

Stratify those seeds by placing them in moist sphagnum moss in the freezer for three months. Then take them out and move them to the refrigerator for two months.

Now you can plant them. Technically, you can try planting without completing the stratification process, but the germination rate will be far lower.

Sow one seed about half an inch deep in a standard potting medium in a six-inch pot. Water well and keep the soil moist as the seed germinates. Place the pot outside in a sunny area.

It doesn’t matter if it snows or freezes, just keep that soil moist and let the seed do its thing. The natural fluctuations will only help the seed to break dormancy.

If all goes according to plan, you should see a little seedling popping up in the spring. Let it grow through the summer and transplant it in the fall. Remember, keep that soil moist and keep the seedling in the sun!

From Cuttings

You can propagate larches from hardwood and softwood cuttings, but softwood cuttings are usually less successful because they require more moisture and regulated temperatures.

Hardwood cuttings take longer to become established, but they’re much more forgiving.

In the late winter, fill a few six-inch pots with coarse sand mixed with perlite. Then, look for a hardwood branch about the diameter of a pencil and up to a foot long.

The donating tree should be young and healthy. Peel it away from the tree so that it has a bit of heel at the end rather than making a clean cut.

Remove about two-thirds of any existing needles from the base and dip the end in your favorite rooting hormone.

Poke a hole in your planting medium. Stick the cutting into the hole about a third of the way deep. Firm up the medium and water well.

Place the pot outside and keep an eye on the moisture of the soil. It needs to stay moist but not wet, and shouldn’t be allowed to completely dry out. Don’t worry if it snows on your cuttings or if the temperature drops below freezing. Remember, these trees are hardy.

Within a few months, you should start to see new foliage emerge. That’s when you know you did it – your cutting has rooted. Continue caring for it in the container until the fall, when it’s time to transplant.

Keep in mind that if you take a cutting from a plant that was grafted onto rootstock, the resulting plant might look different from what you expect.

From Seedlings/Transplanting

The best time to transplant a nursery plant or sapling is when it’s dormant. If there aren’t any leaves, go for it.

That’s not to say that a specimen won’t survive if it’s planted during the growing season, just that it will be happier and more likely to take off if you plant it at the ideal time.

Late winter, early spring, or late fall is perfect, so long as the soil can be worked.

Dig a hole twice as deep and wide as the growing container. Then, mix some well-rotted compost into the soil that you removed and fill the hole halfway back up.

Remove the tree from its container and loosen up the roots. Place the root ball in the hole that you made so that it’s sitting at the same height it was in the container.

Fill in around the roots with the amended soil and add water. If the soil settles a bit, add some more. Keep the soil moist as the tree gets established.

Once your transplant is in the ground, you can expect rapid growth. These trees can add 18 inches per year.

If you plan to grow more than one tree, take its ultimate size into account.

Larches can vary widely in size, depending on the species. If the eventual mature width is expected to be 30 feet, plant at least 15 feet apart.

How to Grow Larch Trees

As we’ve established, shade is not your larch’s best friend. These plants need sun, sun, sun. Plant them somewhere with at least eight hours of sun per day.

The amount of moisture you’ll want to provide depends on the species. Remember, some of these plants grow in swampy areas, and others are used to dry conditions.

Tamaracks (L. laricina) can handle wet, poorly draining soil, but they will be more prone to fungal problems. All the other species generally need well-draining soil.

Despite growing in wet areas, tamaracks will also tolerate some drought. In fact, all Larix species are unlikely to need any additional water once they’ve been established for a year or two.

However, if you have an extended period of heat and drought, plan to give your plants water. It’s always smart to support your trees even if they can survive without you.

If you have average soil, you don’t need to feed your trees. But it never hurts to do a soil test and figure out if your soil is seriously lacking in certain nutrients.

Fertilize specimens that have been in the ground for at least a year as needed, according to the results of your soil test.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full sun.

- Water during long periods of drought.

- Fertilize if your soil is seriously deficient in something, but not otherwise.

Pruning and Maintenance

There’s no need to prune mature larches. You can and certainly should remove dead, diseased, or deformed branches if you see them. Otherwise, leave your tree to do its thing.

The exception is for young plants. Specimens that are five years old or younger can be pruned to encourage a pleasing shape.

Don’t ever trim the central leader, but feel free to prune back the current year’s growth to a leaf bud to encourage branching.

Some of the smaller, shrubbier types can be pruned annually to maintain a more formal shape.

Species and Cultivars to Select

Up until fairly recently, your only option was typically going to be some sort of European cultivar.

Now, you can find more and more North American native cultivars. Here are some of the most common species and best cultivars to pick:

Contorta

‘Contorta’ is a hybrid cross between a European and Japanese larch that really stands out from either species.

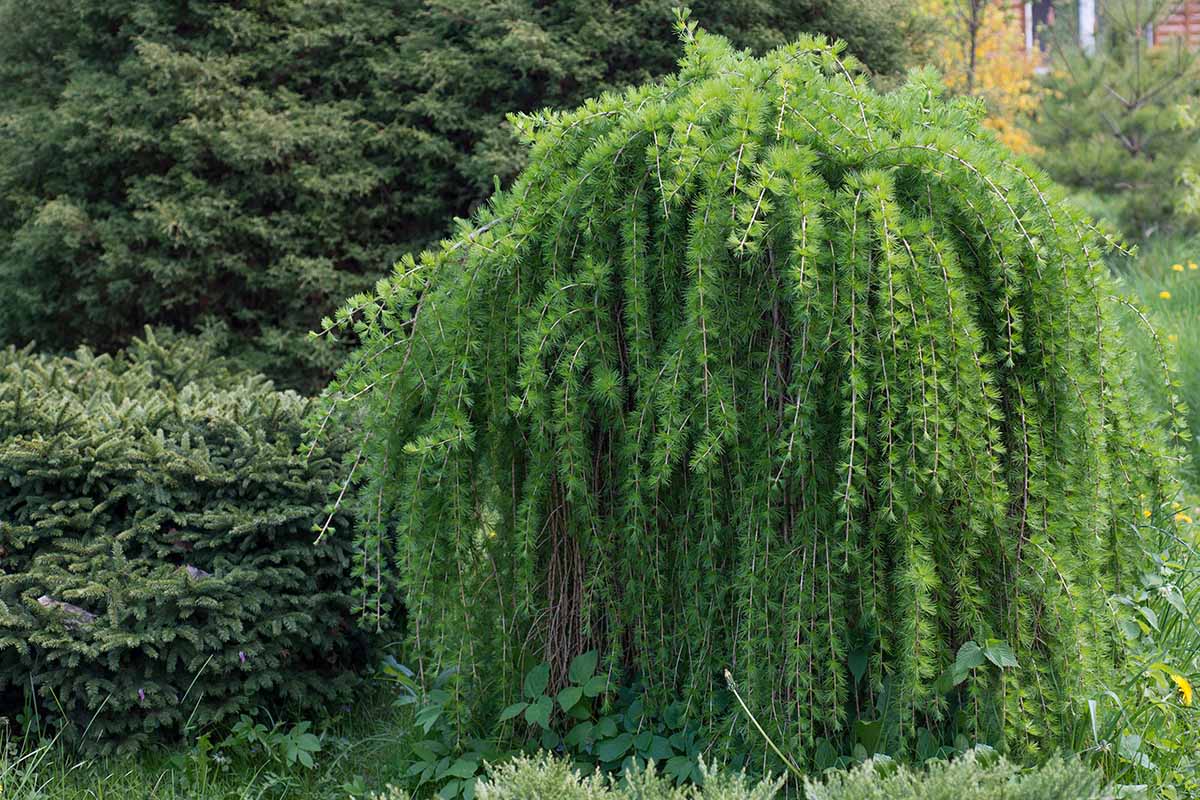

It grows to about six feet with a weeping growth habit and surprising zig-zagging branches that add interest even when the leaves have fallen from the tree. It’s happy in Zones 2 to 6.

European

European larches (L. decidua) are the most common type grown in home gardens in Zones 2 to 6.

There are many hybrids and cultivars, like the weeping ‘Pendula,’ with its gracefully draping branches. If you’ve never seen one before, take a look. They’re truly exceptional.

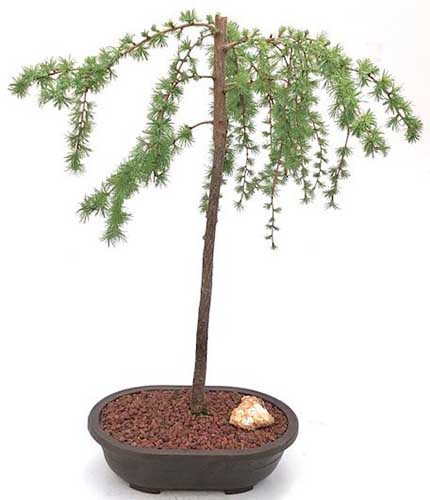

If you’d like to try your hand at growing a bonsai larch, Bonsai Boy has a young potted ’Pendula’ tree available.

‘Horstmann’s Recurva’ is a dwarf type with a spreading growth habit. It reaches about seven feet tall and four feet wide with a pyramidal shape.

‘Summer Belle’ is another dwarf pyramidal type, topping out at six feet tall and three feet wide.

Japanese

Japanese larches (L. kaempferi) grow to about 70 feet tall with a slender, pyramidal shape. They’re hardy in Zones 4 to 8 and are less tolerant of pollution than other species.

‘Gray Pearl’ has bluish foliage and attractive gray bark. In the fall, the leaves turn copper before falling from the tree.

‘Peve Tunnis’ was developed from a witch’s broom and is a dwarf type that mature to about a foot tall and 18 inches wide. The light blue-green foliage turns pink in the fall.

Tamarack

Tamaracks (L. laricina) grow in boggy and swampy areas in their native habitat, which includes Zones 1b to 7a. That should give you a clue as to what kind of conditions they’ll do well in.

Those tough, low areas where water accumulates in your yard? A larch will be perfectly happy to fill in there for you.

‘Ethan’ was cultivated from a witch’s broom and stays under 10 feet, with an oval shape. The light green leaves give way to bright yellow in the fall.

‘Steuben’ has blue leaves on an extremely petite plant that never grows over about four feet. It has a compact, pyramidal shape and golden yellow fall foliage.

Or just snag yourself a species tree from Nature Hills Nursery.

Western

L. occidentalis isn’t quite as cold hardy as the others on this list. It grows in the Pacific Northwest and as far east as Montana, down to Zone 3.

‘Bollinger’ was grown from a witch’s broom found in Montana. Mature plants attain a symmetrical shape and grow to about three feet tall and wide.

Managing Pests and Disease

Young trees are most susceptible to problems. As these trees age, they’re better able to withstand pests and disease.

Insects

Pests themselves won’t usually destroy a larch, but they will leave the tree open to disease.

Neither of these common culprits requires the use of heavy pesticides, which usually leave the biodiversity of your garden far worse off than it started, but do what you can to keep populations in check.

Adelgids

Larch adelgids (Adelges laricis) were introduced from Europe, and they feed on both spruce and larch trees.

The adult flies lay their eggs on larches and they overwinter there, with the larvae hatching in the spring to feed on the plant.

They use their sucking mouthparts to feed on the sap of the tree, leaving sticky honeydew behind as they go.

Most of the time, the infestation itself isn’t the problem, but feeding leaves the tree open to fungal infections where they have pierced the tree. This pest can also cause needles to drop prematurely. On dwarf varieties in garden settings, a large infestation can severely weaken a tree.

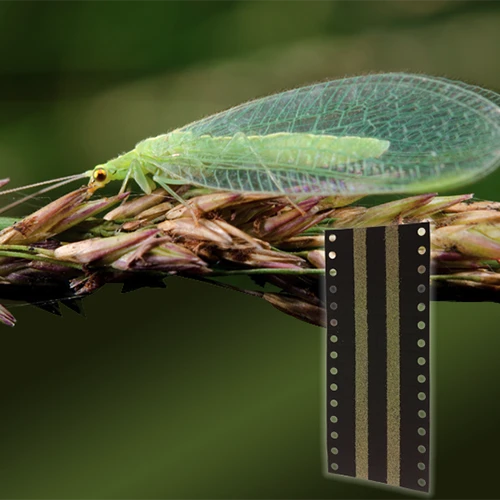

Spray trees with a strong stream of water to knock the pests loose. Encourage healthy biodiversity in the garden, so you will have predators such as lacewings and ladybugs around.

Avoid insecticides as they tend to create resistant populations, and they harm beneficial insects.

Larch Casebearers

The larch casebearer (Coleophora laricella) is a tiny caterpillar that you might assume couldn’t do much damage, given its unimpressive size of under a quarter inch. They leave behind little tan “cases” as they pupate, and it’s easier to spot those than the insects themselves.

But the destruction this pest causes is anything but small. If enough are present, they can completely defoliate a tree.

The larvae poke out of their cases, mining into and feeding on the needles, turning the foliage yellow or tan before it falls from the tree.

Typically, a healthy population of parasitic wasps will keep this pest under control. Combined with some green lacewings, your tree will be fine.

If your garden is short on lacewings, pick up 5,000, 10,000, or 25,000 eggs from Arbico Organics.

Disease

If you place your plants in well-draining soil with some good air circulation, and you do what you can to keep pests away, it’s highly unlikely that your plant will experience any disease issues.

But, never say never. Here are the two big ones to watch for:

Larch Blight

Larch blight is more of a problem in wild trees, but if you’re gardening in an area close to wild trees, it can easily hop to your cultivated tree. You might also bring home a tree from a nursery infected with blight, but this is less common.

Caused by the fungus Hypodermella laricis, it can result in stunted growth and the death of terminal shoots, and young trees might die off entirely.

Browning needles are the first sign of a problem. If left unchecked, blight tends to progress year after year, though it will rarely kill a mature tree.

The fungal spores need water to spread, which is why you’ll usually see this disease start producing notable symptoms in the early summer, after the spring rain has helped the spores spread all over the place.

If your garden has been hit, spray your plant with horticultural oil in the winter to kill off the spores.

Root and Crown Rot

Trees in less-than-ideal environments may be prone to root and crown rot. Caused by oomycetes in the Phytophthora genus, it causes trees to droop and wilt, eventually leading to death of the roots or branches.

Planting in well-draining soil and being careful to avoid overwatering will go a long way toward preventing this disease.

Once it’s present, there isn’t a lot you can do, but our guide to root rot provides some helpful tips on what to do if you catch it early enough.

Best Uses for Larch Trees

The best use depends entirely on the size of your plant.

Obviously, a giant tree is going to do best as a specimen, but some of the lower-growing types can be used as ground covers or work well in borders.

The weeping varieties would make a beautiful anchor for a spot near an entryway or walkway. They’re also a popular option for bonsai or container growing.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Deciduous conifer | Foliage Color: | Green, copper, yellow, gold |

| Native to: | Asia, Europe, North America | Tolerance: | Drought, fire, poor drainage |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 1b-8a | Maintenance: | Low |

| Bloom Time: | Spring bloom, fall leaf color | Soil Type: | Clay to sand |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil pH: | 5.0-7.4 |

| Time to Maturity: | About 10 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 20 feet for full-sized trees | Attracts: | Birds, moths |

| Planting Depth: | 1/2 inch (seeds), same depth as container (transplants) | Uses: | Bonsai, border, ground cover, specimen |

| Height: | Up to 200 feet | Order: | Pinales |

| Spread: | 30 feet | Family: | Pinaceae |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate (juvenile), slow (mature) | Subfamily: | Laricoideae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Larix |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Adelgids, larch casebearers; crown rot, larch blight, root rot | Species: | Americana, decidua, kaempferi, laricina, lyallii, occidentalis, potannii, sibirica |

Larch Trees Are Beautiful and Tough

Larches are pretty unique. A conifer with leaves that change color and drop from the tree? A pine-like tree covered in blossom-like cones? These plants always draw comments and catch the eye.

What kind are you thinking about growing? How will you use it? Share with us in the comments.

If you’re looking for some other landscape trees to add to your space, we have a few more guides that you might find helpful, including: