Rosa sericea ssp. omeiensis f. pteracantha

I’d venture a guess that the thorns are not most people’s favorite part of a rose. The flowers probably take the top spot, though some have exceptionally lovely foliage.

But the thorns? No thanks. If we could do without any part, that would be it, right?

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

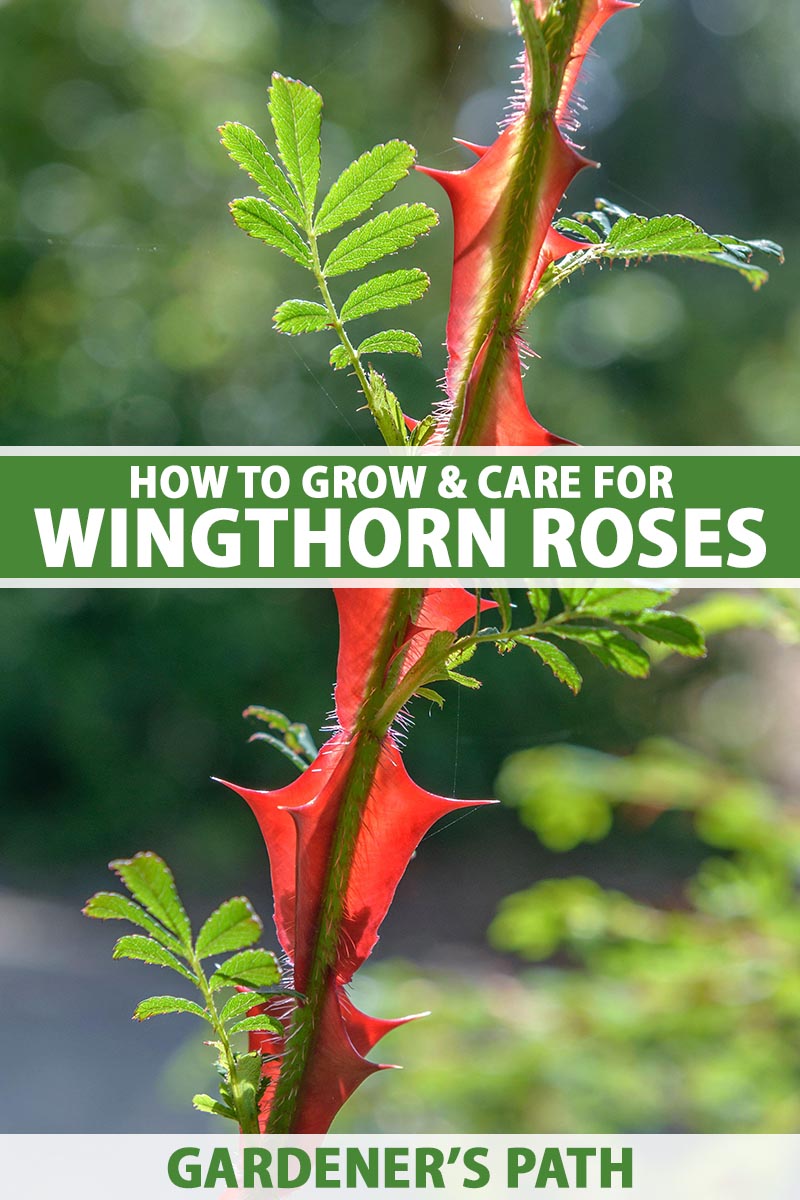

Not so fast. There’s a rose out there that some people love primarily for the thorns. Wingthorn roses do produce flowers, but they’re largely incidental. It’s the bright red, prominent prickles that gardeners celebrate on these unique bushes.

If you’ve ever seen one of these shrubs with its thorns gloriously backlit by the sun, then you totally understand.

The colorful, spiky growths make this plant stand out as an ornamental treasure, even when there isn’t a single flower to be seen.

In this guide, we’ll provide the guidance you need to make wingthorn roses flourish in your garden. We’re going to chat about the following:

What You’ll Learn

Grab yourself some extra-sturdy gardening gloves, because we’re digging into wingthorn roses.

What Are Wingthorn Roses?

Wingthorn roses are well named. They have bright red prickles – what we often call thorns – that extend away from the stem and resemble pairs of dragon wings, complete with dramatically spiked tips.

These thorns spiral up the cane, standing out boldly from the medium green foliage.

You can easily imagine Aphrodite scratching herself on one of these dramatic, inch-long thorns.

However, when it comes to this rose’s botanical name, things are a little less clear. It’s classified as Rosa sericea ssp. omeiensis f. pteracantha, or you may see R. omeiensis var. pteracantha or R. sericea ‘Pteracantha.’

Huh?! Let’s break it down.

Winged roses, as they’re also known, are classified by some taxonomists as being derived from the omeiensis species of the Rosa genus that is native to China. But these are sometimes classified as a subspecies (ssp.) of the very closely related species R. sericea.

The confusion comes from the fact that there are two closely related species: R. sericea and R. omeiensis, both of which have a form known as “pteracantha.”

By the way, form (often written as f.) just refers to a natural deviation of a subspecies. A variety (var.) is a natural variation of a species, rather than a cultivated plant that has been developed by a breeder to have an intended variation from the standard species.

It’s the sericea species that you’ll see for sale at nurseries. Omeiensis wingthorns grow twice as large and have a few other characteristics that set them apart, but both types are native to the same region of China.

Whew!

If you were wondering, “pteracantha” is Greek for wing (ptera) and thorn (acantha).

Beyond the red “wings,” this plant has lacy green foliage, small white blossoms that have just four petals – something that makes it stand out from most other single rose flowers, which have five petals – and bright red hips in the fall.

The older canes are covered in fine, hair-like prickles. The plant itself can grow to 10 feet tall and around six feet wide.

Cultivation and History

These rugged plants originated in the Sichuan Province of China, at the foot of the Himalayan Mountains. They were brought to the US in 1890.

These plants grow best in USDA Hardiness Zones 5b to 9b, though you might be able to get away with growing them in Zone 5a with some protection and the understanding that they’ll die back to the ground each winter here and grow new canes in the spring.

Propagation

Wingthorn roses can be difficult to find at nurseries. If you know someone who has one already (or you have one of your own), you can make more by harvesting the seeds or taking cuttings.

I’ll warn you, however: propagation is difficult. Both seeds and cuttings have a high failure rate.

Still, there’s no harm in trying, and if you find you have a knack for it, you can probably make a ton of cash selling plants to people who admire yours, or produce plenty to share with your friends and neighbors.

From Seed

To propagate wingthorns using this method, save seeds from an existing plant or buy seeds – if you can find them.

We have a guide that can help you through the process of harvesting hips and saving the seeds. Once you have them ready, prep the soil outside for planting.

Wingthorn roses need well-draining, loose soil. If you need to adjust your sandy or clay earth, work in lots of well-rotted compost.

In the fall, plant seeds about a quarter-inch deep and at least two feet apart.

To be on the safe side, you might want to place two seeds near each other and plan on pulling the weaker of the two seedlings if both sprout. Water the soil carefully and keep it moist until the winter rain and snow kick in.

When spring comes around, you should see little seedlings popping up.

If you prefer to plant in the spring, you’ll need to stratify the seeds indoors starting in January. Place them in a bag of moist sand and place them in the refrigerator. Check the bags every week or so to make sure the sand is still moist but not wet.

After three months, they’re ready for planting. Place them in the ground as described above once the ground can be worked.

From Cuttings

As with other roses, you can propagate these by rooting cuttings. Here’s a brief overview of the process:

The best time to take cuttings is when the weather is fairly mild. Take a cutting from soft, green growth, not woody, older growth.

Snip off a piece that is about nine inches long and about the thickness of a pencil. Remove all the leaves from the bottom half of the cutting.

Place in a container filled with potting mix or in prepared soil. Keep the soil moist until roots form.

Read our comprehensive guide on the process of propagating roses from cuttings to learn more.

Transplanting

If you’re lucky enough to be able to find a wingthorn seedling or shrub at the store, nab it!

You’ll plant it as you would any other rose, except these shrubs are a lot more forgiving than some of the fussier roses. We have an entire guide that will walk you through the details of planting a rose to give your plant the best chance of thriving.

In a nutshell, you’re going to dig a hole that is at least twice as wide and one-and-a-half times as deep as the container that it came in.

Mix the native soil with lots of well-rotted compost and place some of this mix back in the hole to make a small cone in the center. You want the plant to sit at the same height that it was in the container.

All this prep might seem unnecessary, but it gives the roots plenty of loose soil to readily become established in, and the cone guides the roots in the right direction.

Remove the plant from the container and loosen up the roots. Place the plant in the hole, spreading the roots over that cone that you made and fill in around it with more of your soil mix. Give it a nice, long drink of water.

How to Grow

These are some of the easiest roses to grow. They aren’t delicate at all.

Once they’re in the ground, keep the soil moist throughout the first year. If you stick your finger into the soil and you notice that it feels dry up the first knuckle, add more water.

The soil should feel like a well-wrung-out sponge during the spring, summer, and fall. Wait until it feels a bit drier before providing any water in the winter.

After the first year as the plant becomes more established, it can handle some drought. The top two inches of soil can dry out at that point before supplementing with more water.

Wingthorns do well in full sun, but in hot regions, they should be protected in the afternoon.

Once every month during the growing season, side dress with a little rotted compost or aged manure. That’s more than enough nutrition to keep them happy.

Growing Tips

- Protect plants from afternoon sun in hot regions.

- Side dress with rotted manure or compost once a month.

- Keep young plants watered well.

Pruning and Maintenance

To encourage more and more of those menacing thorns, prune away one or two of the oldest canes each year in early spring. This encourages young, new canes to grow, which have the most impressive prickles.

You can also deadhead your roses for aesthetic reasons, or leave the flowers in place so they can develop hips. These hips add additional visual interest in the fall and winter, and they’re edible.

Other than that, be sure to prune away any dead or diseased canes if you come across them. You can basically let this beauty do its thing otherwise!

Learn more about how to prune roses in our guide.

Cultivars to Select

This plant hasn’t been cultivated a whole bunch. There is only one commonly recognized cultivar, and that’s ‘Red Wing.’

It looks extremely similar to the parent plant except it is slightly smaller at eight feet tall and six feet wide, and has creamy yellow flowers. The thorns are also brighter in color.

Managing Pests and Disease

The soil pH should ideally be close to neutral or slightly acidic, and something around 6.5 is best for these plants.

This can vary quite widely with no risk of harm to the rose, but if things become too extreme, it can leave the plant in a weakened state and susceptible to diseases.

Wingthorn roses can technically contract any disease or be attacked by any type of pests that other roses can, but it’s rare. Extremely rare.

Like many types of wild roses, these plants are super tough. Here are the most common issues that you might possibly see:

Insects and Arachnids

There are only a few types of pests that feed on wingthorn roses. And even when they do, it rarely results in a problem. I wasn’t kidding when I said these shrubs are tough!

Aphids

Aphids love roses. Any kind of rose. They’re not afraid of thorns, and they’ll use their tiny little sapsucking mouthparts to feed on the sap of the plants.

There are dozens of aphid species that feed on Rosa plants, but the most common are rose aphids (Macrosiphum rosae), potato aphids (Macrosiphum euphorbiae), and cotton aphids (Aphis gossypii).

If aphids attack, it’s generally no big deal. A healthy wingthorn can easily withstand a little problem like aphids.

However, if you want to eliminate them since they can cause yellowing leaves, read our guide to learn how to manage an aphid infestation on roses.

Spider Mites

Spider mites like plants that are experiencing dry, dusty conditions.

If you keep your plant well-watered, it’s unlikely that you’ll have too much trouble with spider mites. They might show up, but they won’t be able to reproduce in large enough numbers to harm your plant.

Look for the fine webbing they produce, which is usually covered in these little spider relatives and their exoskeletons. If you notice webbing, spray down the plant with a strong stream of water in the morning on a sunny day.

If you spray the plant regularly once every four days or so, it should keep pest numbers under control enough that no further treatment is necessary.

Check out our guide to learn more about how to deal with spider mites.

Rose Sawflies

Rose sawflies (Endelomyia aethiops) are an invasive pest from Europe. You’ll see the damage starting in mid- to late spring. The adults are fly-like insects and they’re no big deal.

It’s the larvae known as rose slugs – quarter-inch-long yellow and green caterpillars – that do the real damage.

These caterpillars chew in between the leaf veins, eventually skeletonizing the leaves or causing the foliage to eventually turn brown and die.

It’s ugly, but it’s rarely fatal. And that goes double for these resilient bushes. By mid-June, the caterpillars spin their cocoons and the life cycle continues.

You don’t need to treat this pest if you don’t want to, but if the holey leaves drive you bonkers, coat the leaves top and bottom with insecticidal soap once per week from May through June.

Insecticidal soap is one of those handy things to keep around because it can be used against so many pests and even a few diseases.

If you don’t already have some, Arbico Organics carries 16- and 32-ounce containers of Bonide Insecticidal Soap.

Disease

If you’re looking for a rose that isn’t troubled by disease, this is it. Diseases can potentially infect these plants, but it’s rare that they cause a serious problem that will kill your shrub.

Typically, only wingthorns that are already stressed will succumb to diseases.

Downy Mildew

Downy mildew is caused by a water mold (aka an oomycete) known as Peronospora sparsa.

When this pathogen finds its way to any plant in the Rosa genus, it causes irregular, brown or maroon spots that stay in between the veins. New stems will turn black and die, and you might see white spores on the underside of affected leaves.

Treatment involves a rotating cast of fungicides, and we detail the process in our guide to this disease.

Powdery Mildew

This fungal disease is extremely common. It even shows up on wingthorns, but it’s super unlikely that it will spread across the entire plant and cause defoliation.

If you see the tell-tale powdery coating on the leaves of your plant, pull up our article on controlling powdery mildew on roses.

Rust

If you live in the western half of North America, you’ve probably encountered rust at some point. Those in the rest of the country might see it, too, but it’s less common.

That’s because rust likes high humidity and cool temperatures, something many parts of the West, as well as most greenhouses, have in abundance. Add in some fog or mist and rust is ready to go.

Rust is caused by fungi in the Phragmidium genus and appears as orange-red pustules on the undersides of leaves. The leaves may also turn brown or yellow and fall off the plant.

It’s possible to control or eliminate the fungi using a copper fungicide.

Grab a 32-ounce ready-to-use, 16- or 32-ounce hose end, or a 16-ounce concentrate container at Arbico Organics and saturate the leaves, top and bottom, as well as the stems and any flowers. Repeat every 10 days until the symptoms are gone.

We have more tips on preventing rose rust here.

Learn more about diseases that affect members of the Rosa genus here.

Best Uses

One wingthorn is great, but a group? Divine. Planted in clusters, the bright red thorns and stems stand out as even more of a statement.

Of course, these also make a lovely specimen, or they can complement other roses well, especially when combined with white or yellow ones to contrast with the red thorns.

You probably don’t want to grow this shrub too close to a walkway because those thorns will grab you.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Woody flowering shrub | Flower / Foliage Color: | White, pale yellow/green; red thorns |

| Native to: | China | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 5b-9 | Soil Type: | Loose, loamy |

| Bloom Time: | Year-round interest, blooms in summer | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.5 |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 6 feet | Attracts: | Butterflies, bees |

| Planting Depth: | 1/4 inch (seeds), same depth as container (transplants) | Companion Planting: | Marigolds, chrysanthemums, geraniums, sweet alyssum, rue |

| Time to Maturity: | 4-5 years | Avoid Planting With: | Cane berries |

| Height: | Up to 10 feet | Uses: | Specimen, groupings |

| Spread: | 6 feet | Family: | Rosaceae |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate | Genus: | Rosa |

| Water Needs: | Low to moderate | Species: | Sericea |

| Tolerance: | Some drought, depleted soil | Subspecies: | Omeiensis |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, spider mites, rose sawflies; downy mildew, powdery mildew, rust | Forma: | Pteracantha |

Sometimes the Thorns Are the Best Part

I can’t blame anyone who balks at the idea of choosing a rose for its gnarly thorns, but once you see how stunning these plants are, you’ll understand the appeal of those prickly protrusions.

The striking red growths stand out from anything else growing nearby. Just don’t look too close! You might poke your eye out.

Where do you plan to put your rose? Is it going to stand out singly as a bold specimen statement? Will you group several together for a formidable display? Let us know in the comments section below.

If you’re looking to expand your rose garden, we have lots of guides that we hope you’ll find useful. Here’s a sampling of several recommended places to start:

Very helpful in making my decision to relocate my specimen, thanks.

Thanks for reading, Andy!