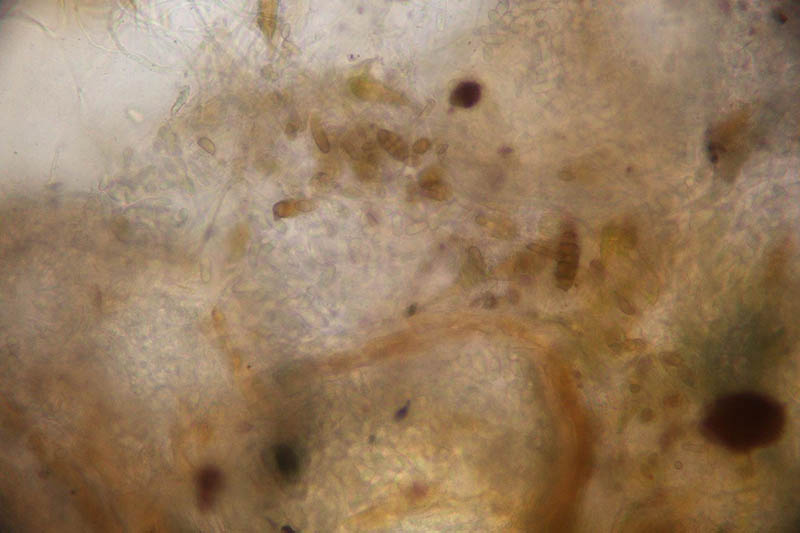

Pleospora herbarum

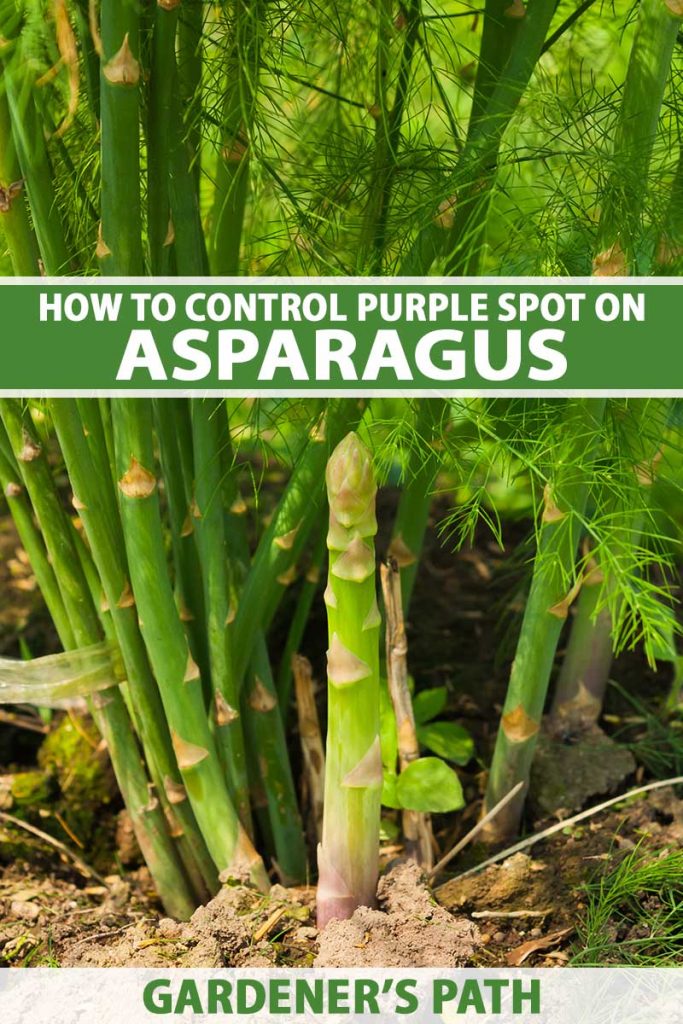

Purple spot is an asparagus disease that can infect between 60 and 90 percent of the new spears when conditions are right.

Most prominent in cool weather, it typically subsides when conditions become dry.

The disease manifests as small, superficial, reddish-purple lesions on the lower half of new spears. In addition, tan to brown lesions can form on the needle-like leaves of the ferns.

Fortunately, affected plants are edible, and the spots disappear during cooking.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

But you should still take steps to protect your crops, and treat them if needed. This disease can predispose asparagus plants to crown rot and result in an early death.

Read on to learn how to control this disease.

Asparagus Purple Spot

Life Cycle

You may not know that fungi can alternate between sexual and nonsexual stages. They produce different kinds of spores, look like entirely different organisms, and are named differently!

This is highly relevant to gardening, because the spores produced by these two stages can infect the plants differently.

The disease is most intense when debris from the previous year’s fern growth is lying around on the surface of the soil. This is a particular problem when no-till cultural systems are used.

Fungi in the sexual stage (Pleospora herbarum) live on that debris, and it is ready to infect the new spears when wet weather strikes in the spring.

Fungi at this stage produce ascospores that live within a sac-like structure called an ascus. These asci are produced in structures called pseudothecia that look like small black dots on the asparagus debris.

These ascospores infect the spears as soon as they emerge from the ground. The fungus does not require wounds to infect the plant, although their presence can increase the incidence of purple spot.

Lesions are often found on the windward side of the spears, where wounds are caused by blowing sand.

Next, the infection continues in the asexual stage (Stemphylium vesicarium). The fungus then produces spores known as conidia that are easily disseminated.

It’s bad enough that these spores spread through the air, but the fungus also keeps producing batches of them!

These conidia enter through wounds and stomata, the pores in the leaves that the plants use to breathe. The disease continues progressing as the ferns develop.

The early death of the fern limits the ability of the plant to conduct photosynthesis, which results in fewer sugars in the crown for the crop to use to grow in the following year.

There are several severe effects from this reduction in photosynthesis:

- The quality of the spears is reduced, and yields may be lower.

- The plant becomes more susceptible to Fusarium and Phytophthora, which can severely damage the crowns.

- Your plantings may die an early death.

Conditions that Favor Disease

This disease is more severe in cool, wet weather, when the spears are emerging from the ground.

Outbreaks can appear breathtakingly quickly, since plants can become infected in as few as three hours.

For example, there was a case in Connecticut in which the spears were being harvested and appeared to be free from purple spot.

However, all the spears became infected following two days of wet and cold weather. When the weather improved, the new spears were disease free.

Control

To prevent this disease from occurring, remove the fern growth at the end of the season.

It is best to remove it from your yard rather than incorporating it into the soil, which can damage the roots and crowns.

It’s important to note that this damage can lead to another disease – Fusarium crown and root rot.

States vary in whether or not they permit fungicides to be used against purple spot.

For example, in Michigan, home gardeners can use the fungicide chlorothalonil, sold as Bonide Fung-onil Concentrate, available from Tractor Supply, to control this disease.

However, California does not recommend chemical treatments for purple spot.

Purge Asparagus Debris from Your Garden at the End of the Season

Since purple spot survives the winter on asparagus debris, getting rid of this material will go a long way towards limiting new infections.

However, tilling the debris into the soil can damage the crowns of the plants and possibly lead to crown rot. Bagging up this material and removing it from your garden is recommended.

Since fungicides are used to treat this disease in some states but not others, you will need to check your local laws.

Fortunately, purple spot is no longer a problem when the weather transitions from cool and moist to warm.

Have you had purple spot in your asparagus patch? If so, let us know how you fared in the comments section below.

And for more information on growing asparagus in your garden, check out these guides next:

- Great Tips: A Grower’s Guide to Asparagus

- What Is Asparagus Rust?

- What’s the Difference Between Male and Female Asparagus Plants?

- How to Identify and Control Common Asparagus Diseases

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photo via Bonide. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. With additional writing and editing by Allison Sidhu.