For those seeking to cultivate a resilient, healthy organic garden, Jessica Walliser’s book “Plant Partners: Science-Based Companion Planting Strategies for the Vegetable Garden” should be one of your essential reference books.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Organic gardeners, polyculture enthusiasts, pollinator protectors, and permaculturists alike will all be enlightened by this highly informative and extremely practical guide to companion planting.

You can find “Plant Partners” now on Amazon.

For a deep dive into this book, keep reading our review – here’s what we’ll cover:

Plant Partners: A Look Inside

First Impressions

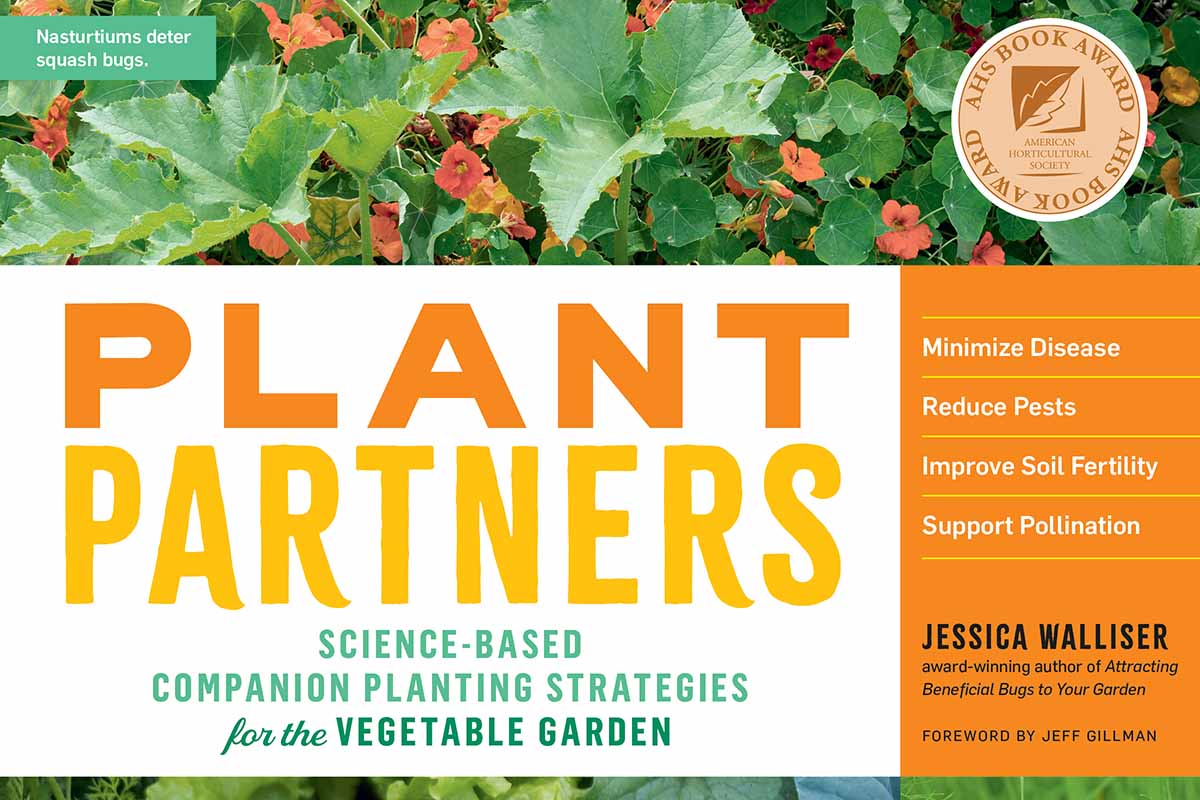

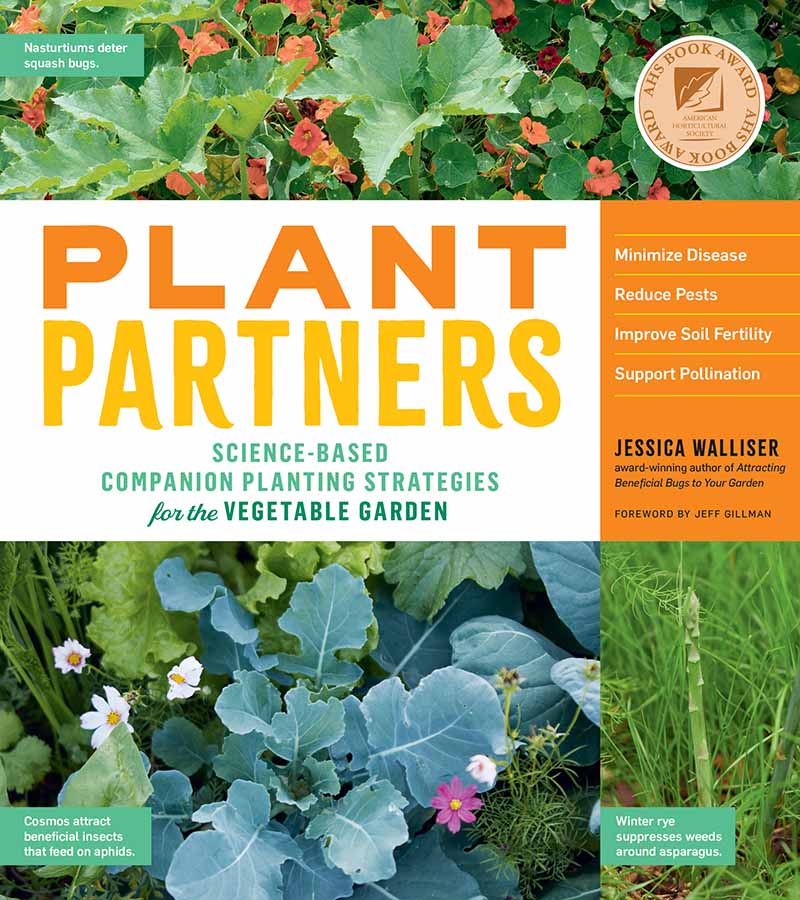

We all know we shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, right?

Well, you can drop that adage for now – go ahead and judge. The colorful front cover of “Plant Partners” provides a perfect hint of what you’ll find inside!

Plant Partners, Available via Amazon

A flip through the book reveals a thoughtful and colorful design brimming with as much color as a polyculture garden.

Unlike some companion planting books, this volume doesn’t just tell you what pairings you can try – it shows you, too. It is jam-packed with gorgeous photos of successful garden partnerships.

Colorful text boxes scattered throughout the book offer insights into different pairings and answer frequently asked questions such as, “How close do companion partners need to be?”

The book measures eight by just under nine inches, making it easy to open wide and view its 224 pages.

The pages of the book are matte, not glossy, making this volume feel like it’s ready to help you get to work rather than just sitting prettily on your shelf.

Beyond its colorful and striking design, one of the first things I noticed after turning the first few pages was that “Plant Partners” is published by Storey Publishing.

Known for their books on the topic of creative self-reliance, whenever I come across a book released by this publisher, my brain perks up and I know good things await.

Another personal point of excitement I found in the first few pages was a foreword written by Jeff Gillman, currently the director of the UNC Charlotte Botanical Garden program, where I earned a certificate in Native Plant Studies.

Gillman is the author of several gardening books of interest, such as “The Truth about Organic Gardening: Benefits, Drawbacks, and the Bottom Line,” also available on Amazon.

The Truth about Organic Gardening

Once you start flipping through “Plant Partners,” you’ll likely be drawn in immediately, either by the beautifully designed chapter introductions, the eye-catching photos of happy companion groupings, or the attention-grabbing section titles.

However, before we dive in, let’s return once more to the cover.

“Plant Partners” bears the emblem of an American Horticultural Society (AHS) Book Award. Quoting from the AHS website, recipients of this award are judged on “qualities such as writing style, authority, accuracy, and physical quality.”

Spoiler alert – by the time I reached the end of this book, I wholeheartedly agreed that Walliser’s writing was worthy of this award.

Judging this book by its cover and by a quick overview of its inner pages, I was eagerly looking forward to immersing myself in “Plant Partners.”

Let’s dive in. But first, a quick look at the writer behind this fantastic publication.

Who Is Jessica Walliser?

Jessica Walliser, the author of “Plant Partners,” is a horticulturist and garden writer who trained at Penn State University.

Walliser’s writing has appeared in Fine Gardening, Hobby Farms, and the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. She cohosts “The Organic Gardeners,” a radio show broadcast in Pittsburgh.

In addition to this impressive resume, Walliser is also one of the co-founders of the website Savvy Gardening.

Those who are fans of her writing will be thrilled to learn that “Plant Partners” is not her only book – she has authored four other titles as well.

You can read our review of her book, “Gardener’s Guide to Compact Plants,” right here.

Section By Section

Along with a foreword, introduction, and epilogue, “Plant Partners” contains eight chapters. It also includes a page of resources, a glossary, and a bibliography.

The research studies listed in the bibliography inform the pairings proposed throughout the book.

Let’s get started with a detailed look at this companion growing guide, examining the contents of the book’s various sections and chapters.

Introduction

In the introduction to this book, Jessica Walliser gets us prepared for where we’ll be traveling with her – on a path that veers away from traditional companion planting lore.

Why this break? Traditional pairings are often repeated but not always verified. Instead, Walliser will be introducing us to partnerships that stand up to scientific scrutiny.

This scientific approach has multiple benefits – it allows us to use proven combinations in our own gardening endeavors, but also to understand the why and how of successful combinations, enabling us to make our own companion groupings.

In addition to setting us up for a scientific approach to the subject, Walliser’s introduction encourages us to see our own backyard landscapes as ecosystems, where plants have different relationships to each other.

The Power of Plant Partnerships

The first chapter expands on the introduction, heralding a modern approach to companion planting as well as a movement away from monoculture gardening – the type of agriculture where one might find an entire field of soybeans, or a solid row of watermelons.

The author describes the types of research that have been conducted in this area – and why this research is relevant to those growing their own food at home.

Encouraging us to see our gardens in a different light, the author mentions that mycorrhizae are at work not just in forests but in our edible landscaping too, and explains that allelopathy, often cited as a gardener’s problem, can be used to our benefit.

Walliser reminds us that diversity should be a goal in our gardens, pointing out that these created landscapes play important roles for providing small creatures with habitat as their natural habitat is lost to development.

She also encourages us to see that plants are not passive inhabitants of our edible landscapes, but are instead actively affecting each other through various means: chemical messaging, fungal associations, and allelopathy, as well as sharing resources, attracting pest predators, and improving nutrient availability and absorption.

Walliser lets us know that it’s these different effects we’ll be exploring in the rest of the book, with each remaining chapter showcasing a different benefit of companion planting.

Soil Preparation and Conditioning

Chapter two takes a look at how companion partnerships can improve soil via cover cropping, nitrogen transfer, and the breaking up of heavy soils.

Coming back to the fascinating subject of mycorrhizae, the author discusses the role of fungal networks in garden soil and how these networks function for annuals.

On a very practical level, we learn how to best use oats, cowpeas, buckwheat, crimson clover, winter wheat, and winter rye to our advantage in a home garden. We also learn the pros and cons of turning these crops under versus leaving them for mulch.

You may be well aware of the nitrogen-fixing abilities of legumes, but do you know which legume crops are the best at doing this job? I didn’t – until I read this chapter!

Walliser provides five examples of successful legume and vegetable crop combinations. One of my favorites I learned here was cowpeas and peppers, which I’ll be trying out in my own summer garden.

And for growers concerned with heavy or compacted soils, we also learn which crops have roots that are good at drilling into this type of earth.

One of these was a surprise to me – buckwheat. This annual is commonly used as a cover crop or green manure, but I wasn’t aware that it is also able to improve soil structure through its root exudates.

Weed Management

Chapter three focuses on managing weeds through the use of living mulches and allelopathic partners.

Unlike cover crops which are generally grown before the main crop, living mulches are grown with crops at the same time to cover and protect the soil.

Walliser explains how to successfully use living mulches without letting them get in the way of your main crop.

Among the examples offered for living mulches are several different types of clover, each used with a different harvestable crop.

And this chapter also gives us a look at using allelopathic species to control weeds – perhaps one of the least-known uses of companion partnerships in popular gardening lore.

I have to say, this section cleared up a big, dark cloud of confusion that has been hanging over my head as to why some species are allelopathic in some cases but not in others.

Not stopping at the merely theoretical, Walliser explains when an allelopathic partner can be protective, and in which cases it can be counterproductive – and provides examples that can easily be tried out in the home landscape.

Support and Structure

Chapter four proposes creative options for plants that can be used as living trellises for other crops.

You’ve heard, no doubt, of the traditional three sisters crop grouping – corn, pole beans, and squash?

Using corn as a support for pole beans is one of the most commonly cited companion partnerships and is a prime example of a living trellis.

Walliser provides practical advice for making such combinations work in our gardens, with 11 additional living trellis combos to try.

One of these I’m excited to try in my own edible landscape is using my Jerusalem artichoke patch as a trellis for tiny cucamelons, or mouse melons as they’re sometimes called.

Pest Management

In chapter five, we learn about four different ways that companion groupings can help with pest management: luring, trapping, tricking, and deterring.

Before we get into specifics, Walliser gives us a reminder of how pests find their target species in the first place, and clears up the difference between repelling versus masking.

First, we explore trap cropping, a technique where a veggie crop is spared pest infestation by luring pests to an even more desirable one.

One example she cites is using the ‘Blue Hubbard’ winter squash to attract pests away from other varieties of squash.

Along with providing useful tips on how to distance a trap crop from a harvestable crop and what to do with an infested trap crop once you have one, the author provides guidance for different types of pests – ones that are “highly mobile,” such as squash bugs, and ones that aren’t, such as flea beetles.

Also discussed in this chapter are masking strategies – ways to “hide” crops from pests.

One of the combinations the author suggests is the classic companion combo (and Italian food pairing par excellence) of tomatoes and basil, in which the herb protects the nightshade veggie from thrips.

Interfering with egg laying is the next topic we encounter in this chapter, where we learn that companion planting can help to throw a wrench into the reproductive plans of pests. Walliser provides us with six proven combinations for this strategy.

Finally, this chapter offers solutions for impeding pest movements. One of these is essentially an ode to the hedgerow, which I find in and of itself to be worthy of the price of the book.

Disease Management

Chapter six examines the prospect of managing soilborne diseases using cover crops and living mulches.

One might not consider disease management to be an obvious benefit of companion partnerships. You may have heard, for instance, that hairy vetch makes a good cover crop. But did you know it might protect your tomatoes from certain diseases?

In “Plant Partners,” Walliser offers proof of this concept through six different combinations that have been demonstrated to be successful in research conditions, and can be recreated in the home garden.

Biological Control

Chapter seven focuses on biological control – that’s to say, keeping pest populations in check by attracting pest-eating, beneficial insects.

My first thought when digging into this chapter was, how is this different from pest management?

The answer is – it’s not. It is part of pest management.

However, chapter five (the one titled “Pest Management”) focuses on how plants themselves can be used to redirect pests, while this chapter looks at controlling pests with the help of beneficial insects and spiders.

In this chapter, we learn how to attract these garden helpers as well as how to create habitat for them.

This is obviously a subject dear to the author’s heart, as demonstrated in one of her other books, “Attracting Beneficial Bugs to Your Garden: A Natural Approach to Pest Control,” which is also available on Amazon.

Attracting Beneficial Bugs to Your Garden: A Natural Approach to Pest Control

On the topic of attracting beneficial insects, we learn about several specific combinations that will help control aphid populations, as well as pairing recommendations for controlling other pests.

This chapter also offers suggestions for creating habitat for beneficial insects, since habitat and forage aren’t always found simultaneously among the same species.

Walliser offers solutions for various types of insect habitat, from low-growing ground covers to more substantially landscaped hedgerows.

If you’ve heard it’s a good idea to leave the dead growth of your garden annuals over winter as insect habitat, you might wonder when it’s safe – for your bug buddies – to remove this dead material. Walliser has an answer to this question.

This chapter also includes an excellent discussion of the merits of purchasing beneficial insects for release versus focusing on attracting local populations of the same insects.

And if you haven’t yet gotten the message that the guiding principle of companion planting is about creating a diverse landscape, you’ll get it in this chapter.

Pollination

The eighth and final chapter of Walliser’s book is about pollination.

If you didn’t think of pollination as being one of the goals of companion partnerships, consider this: Many of our crops depend on the efforts of pollinators in order to produce harvests, after all – and companion partners can bring in droves of pollinators.

While the honeybee may be the poster child for the “save the pollinator” movement, Walliser shines a light on the many native pollinators that are at work in our gardens, and points out they don’t tend to get the credit they deserve.

The first part of the chapter offers five companion pairings to attract pollinators, while the second part provides advice on creating nesting habitat for pollinators.

One of the highlights of this chapter for me was the author’s description of squash bees, which both forage from and curl up to sleep in squash blossoms.

I’ll be heading out to my squash patch at night this summer to peek into the blossoms and check for these reposing native bees!

Final Thoughts

Digging deeply into this book as I have done, I have come away a definite fan.

The content presented here is well researched and well presented, and Walliser’s language is both informative and engaging.

I kept my typo radar on while reading and only came across a handful of minor errors – the book is both extremely well-written and well-edited.

However, that’s not to say I don’t have any criticisms to offer.

One of my quibbles is with the index. I searched the index for a couple of specific subjects – marigolds and eggplant – and found that it came up short.

Eggplant is listed in the index as appearing on pages 57, 152, and 153, but while it is also featured on pages 170 and 171 under the topic of growing large or hooded flowers to attract bumblebees for improved pollination, these references were omitted from the index.

As for marigolds, they are showcased in the “Pest Management” chapter as a good companion to use with onion and cole crops. Yet poor little marigold was left out of the index altogether.

But perhaps I am a bit of a stickler on this point – I appreciate a well-packed index.

My only other complaint with this book lies in the printing medium, specifically the paper choice.

With Walliser’s encouragement to create habitat for small creatures as a replacement for dwindling natural habitat, the author – and the publisher, for that matter – seem to have a strong commitment to environmental protection.

I would have hoped that their dedication would extend to choosing recycled paper to print the book on, but alas, that appears not to be the case.

Again, this is another point where I’m a stickler. I can only hope when the second edition of the book is released (as I heartily expect it one day will be!) that recycled paper will be considered as an option that’s more in keeping with the underlying principles championed in the publication.

It is, of course, available in digital format as well, and the Kindle edition may be purchased on Amazon.

Putting these two issues aside, perhaps you’re wondering who might benefit the most from reading this book?

“Plant Partners” is useful for newbies to companion planting as well as well-seasoned polyculturists. Those of us who have been using traditional companion pairings for decades will have many opportunities to expand our knowledge with Walliser’s book.

This publication can be read from cover to cover as a fascinating book about the ideas behind companion partnerships. And it can also be used as a highly practical reference book, illustrating dozens of specific partnerships that can solve specific garden problems.

Plant Partners: Science-Based Companion Planting Strategies for the Vegetable Garden

Much like gardening itself, this book offers fascinating glimpses into the natural world. “Plant Partners” is not just about growing food, it provides an impetus to “grow nature” and to allow our gardens to “become a safe harbor” for the many creatures that live and act in our own outdoor landscapes.

As for myself, this publication has earned a spot on my shelf with my other essential gardening references – and I eagerly await future works from the same author.

Have you read this book? Tell us what you thought in the comments section below!

And if you’re still building your personal gardening reference library, you can check out some of our other book reviews right here: