Allium cernuum

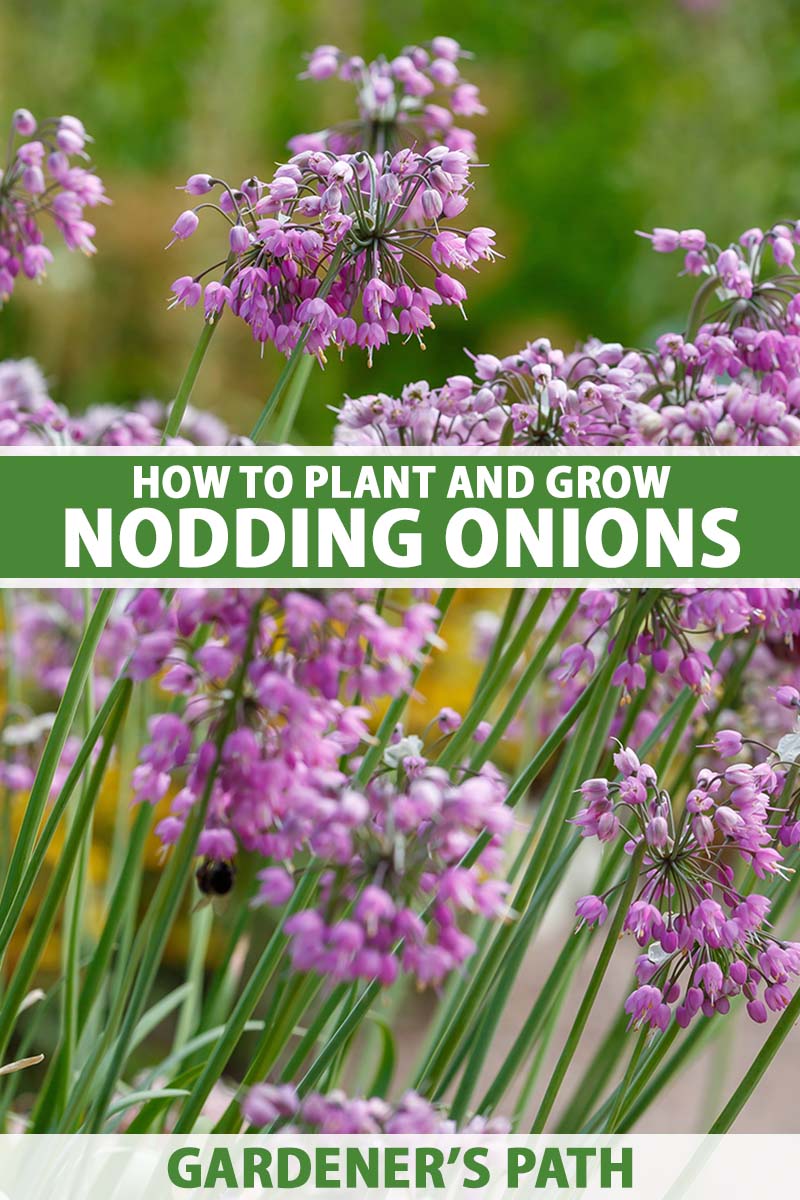

The sweet, airy umbels of the blooms of nodding onions fill a much-needed niche in the garden.

Blooming at the height of summer in hot, sunny locations with dry soils, these wildflowers thrive where others falter.

Use them in a rock garden, along a brightly lit woodland edge, or in a long forgotten meadow.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Read on to find out more about growing this North American native that’s a favorite of bees and other pollinators.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Nodding Onions?

A member of the amaryllis family, Amaryllidaceae, Allium cernuum is an ornamental allium that – if you dig it up – looks a lot like the culinary staple you might have eaten for dinner last night.

Grocery store onions and nodding onions, also known as lady’s leeks, are species in the Allium genus, and both grow a stout, pungent, underground bulb.

The bulbs of nodding onions are much smaller and narrower than those we typically use for cooking and they are edible. Several narrow, grass-like leaves, which also smell strongly of onions, arise from the neck of the elongated bulb.

The flower stalks can grow up to 30 inches tall and emerge from the base of the leaves in summer, supporting an open cluster of pendant flowers ranging in color from white to pale lavender to pink.

Just below the umbel, the scapes bend downward like a crook-handled walking stick, giving the plants their “nodding” appearance.

In late summer and early fall, flower heads dry and form papery capsules that split open to reveal lots of hard, shiny black seeds.

Hardy in Zones 4 to 9, this garlic relative can be found growing wild across most of North America. Preferring bluff edges and rocky outcrops, nodding onion doesn’t really take off and spread unless it’s planted in nutritious soils.

In the more moist, rich soils of riparian habitats, or in fertile meadows, this species can colonize large areas by self-seeding.

Keep reading to learn how to get this North American native established in your own garden.

Nodding Onion Propagation

Nodding onion can be grown from seed, via offsets, or transplants you purchase from the nursery.

The process for all three methods is pretty straightforward. These plants are truly a breeze to grow.

From Seed

Starting A.cernuum from seed is a fun, rewarding process that typically yields lots of new plants.

To collect your own seed, start to keep an eye on the flowers when they are in bloom in the summer.

If you are planning to collect seed from wild populations, ensure that you have permission to enter the area and only take about 10 percent of the seeds.

When the leaves have senesced and the upright umbels turn light brown, snap off the tops of the seed heads with your fingers and collect them in a paper bag.

Let these seed heads dry in a tray in a cool, well-ventilated, dimly lit place until the capsules split open to reveal black, shiny seeds. I like to use my closet for air-drying seeds.

Prepare a planting tray with moistened potting soil. Scatter the seeds liberally across the surface of the soil.

Gently press them into the surface of the soil with the palm of your hand to ensure good soil contact then scatter several handfuls of moist potting soil across the surface of the tray so the seeds are barely covered.

Move your tray somewhere outdoors that’s protected from wind and extreme temperature fluctuations.

You want the seeds to experience stable, cold temperatures for a period of 30 to 60 days. This process, called cold stratification, prepares the seeds for germination. Keep the potting soil evenly moist but not waterlogged.

In the spring, pull your planted tray out into a location that receives full sun and make sure the soil stays moist, but not soaking wet.

After germination occurs, your tray will look like it’s suddenly growing a furze of green grass!

Rest assured, these are your new baby nodding onions. When they are about an inch tall, thin out the seedlings so there is at least half an inch of space between each plant.

Once your seedlings reach a few inches high you can move them into their own prepared pots. Two- to four-inch pots or cells work nicely for this.

Fill the containers with moist potting soil and poke holes with a stick or pencil. Carefully transplant the tiny bulbs.

Keep the potting medium evenly moist and set the pots in an area that’s protected from wind and receives full sun. The plants can be transplanted into the garden in fall or the following spring.

As an easier alternative, you can simply broadcast fresh nodding onion seed into the garden immediately after collection.

Prepare the area for sowing by gently raking the surface of the soil and then raking again once the seed is cast. Water liberally after sowing, and let Mother Nature take care of the rest.

From Offsets

Almost all members of the Allium genus form little baby bulbs or “offsets” on the original bulb.

Digging up and separating offsets then replanting them is one of the easiest ways to increase your patch of nodding onions, although it will take about two years for these baby bulbs to grow to flowering size.

In the fall, after the leaves of the plants have withered away and their flowers have set seed, gently pry up the bulbs. Make sure to do this very carefully to prevent damage to the bulbs.

It’s easy to get a little overzealous while digging and split your plants’ bulbs in two. Use a larger shovel than you think you’d need and use your fingers to tease the bulbs gently out of the soil.

Carefully separate the offsets from the parent bulbs and replant them about two to three inches deep and about four inches apart. Make sure you replant the original bulbs too.

Transplanting

Whether you have started your own baby nodding onions from seed, purchased plants from a nursery, or are replanting offsets, transplanting is a simple process.

Make sure you select a location in the garden with full sun and freely draining soil.

Dig a hole deep enough so that your bulbs are planted at the same depth as they were in the pot they are currently growing in.

In the case of offsets, plant them two to three inches deep. Backfill the hole with soil around your plants and water well.

How to Grow Nodding Onions

As with most plants, the secret to growing a happy, thriving patch of nodding onions is choosing the right location.

In the wild, they grow in a variety of places, including open meadows, rocky outcrops, and sunny, forest glades.

The one characteristic these diverse habitats have in common is freely draining soil and ample light exposure.

Generally speaking, bulbs tend to not do well in wet to consistently moist soils, and nodding onion is no exception.

Grow A. cernuum somewhere with abundant sunshine, though a little afternoon shade is okay, particularly in warmer locations, and make sure the soil drains well. Even hot, dry soils don’t bother nodding onions.

This species can tolerate sand and some clay as well, so long as it won’t become waterlogged or stay damp for too long.

The ideal soil pH is 6.0 to 7.0, but the plants will tolerate alkaline soil and are even suitable for growing near black walnut trees, as they are tolerant of juglone.

Thriving in USDA Hardiness Zones 4 to 9, nodding onions can tough it out in all but the coldest climates.

Planting these bulbs in a garden bed adjacent to a south facing wall or within the protection of a rock garden might allow you to grow nodding onions in Zones 3, or lower, as well.

Once established, just enjoy the tenacity of this robust species. Fertilization is not required, nor is supplemental watering, unless you experience a real drought with no rainfall for more than two weeks.

Growing Tips

- Plant in freely draining soils.

- Site in a location with full sun or a little afternoon shade.

- Water well during any very dry periods.

Maintenance

A wonderfully unfussy native, there’s not much to do when it comes to taking care of nodding onions.

In late summer, after flowering, the leaves will start to soften, turn yellow, and die back. At this point, you can remove and compost the foliage to tidy up the garden.

To see if your plants’ leaves are truly ready to be removed, just give them a gentle tug. If they come away easily in your hand, they’re ready. If they don’t, let them be for another week or two.

The dry flower heads that stand above the wilting foliage will soon ripen and reveal masses of shiny, black seeds.

If you don’t want to allow A. cernuum to spread throughout the garden, remove the flower heads before the seed ripens. A good time to do this is right after flowering, but any point before mid-fall will do the trick.

Nodding onion spreads particularly well in the nutrient-rich soils commonly found in garden beds, on the edges of woodland areas, and untended lawn. In dry, rocky situations, they tend to proliferate much more slowly, if at all.

Nodding Onion Cultivars to Select

If you want to get started growing nodding onion in your garden, you can find plants available at Nature Hills Nursery.

There are a few cultivars available as well, mostly with minor variations in flower color.

Hidcote

Winner of the prestigious Royal Horticultural Society Award of Garden Merit in 1993, ‘Hidcote’ grows up to 13 inches high and boasts lovely rose colored clusters of flowers.

Blooming slightly earlier in the summer than the straight species and other cultivars, ‘Hidcote’ is a real favorite for late spring displays. This cultivar is hardy in USDA Zones 3 to 9.

Leo

‘Leo’ grows a little taller than other cultivars at almost 30 inches tall. The flower heads are white, and more densely clustered, too.

Notably, ‘Leo’ is typically in full bloom in August, later in the summer than the species and other cultivars.

Oxy White

Once regarded as a separate species, A. oxyphilum, this white-flowered variety is now considered a form of A. cernuum.

Hardy in USDA Zones 4 to 9, the flowers of ‘Oxy White’ are a little more airy and delicate than the straight species.

Managing Pests and Disease

Blissfully problem-free, there is very little in the pest and disease department to truly plague nodding onion.

Most issues arise when these bulbs are improperly situated in consistently wet soils. Give these native wildflowers the freely draining substrate they desire and they’ll grow quite happily and without trouble.

Pests

Thanks to its strong aroma, not very many insects bother nodding onion. There’s really only one to look out for, and that’s thrips (Thrips tabaci).

These pesky insects are about teeny tiny, about a twelfth of an inch long, pale brown in color, and have delicate, fringed wings. Their young look similar, minus the wings.

Although thrips can cause problems for all members of the Allium genus, they also feed on cucumbers, tomatoes, and cabbages.

Feeding damage on nodding onion appears as white to silver blotches on leaves, wilting foliage, reduced bulb size, as well as decreased flowering and pollen production.

Female thrips produce up to eight new generations of young per year, laying eggs on the underside of the leaves.

Populations expand most quickly in hot, dry weather when plants may already be stressed.

To avoid damage from these pests, keep your nodding onion patch in good health. Site plants in an appropriate location, in freely draining soil with plenty of sun.

Fortunately, A. cernuum is not very susceptible to these insects and shouldn’t suffer too much damage from an infestation.

You can learn more about how to manage thrips in our guide.

Disease

Unlike its vegetable cousins, there are almost no diseases that plague this wild allium.

The two issues you may encounter are easily avoided by siting A. cernuum in the freely draining soils it loves.

Downy Mildew

A common disease of all the plants within the Allium genus, downy mildew is caused by a water mold, Peronospora destructor, that thrives in high humidity and cool temperatures.

Spores land on the foliage and cause discolored splotches, yellowing leaves, and even dieback.

This disease is easily controlled by watering at the base of the plants, rather than from overhead. If you notice any affected plants, remove the entire bulb and destroy it.

Planting A. cernuum in full sun, in freely draining soils will almost completely protect these plants from downy mildew infection.

White Rot

Another disease common to the edible onions we grow in our vegetable gardens, white rot, a fungal disease caused by Stromatina cepivorum, is not commonly seen in A. cernuum.

If you happen to get very unlucky and discover this fungus infecting your wildflowers, you’ll notice yellowing, dying foliage.

Underground, the bulb will turn black and rot. Pull your plants immediately and destroy them by discarding in the garbage. You definitely don’t want to spread this destructive pathogen elsewhere in the garden.

Thankfully, white rot is once again easily avoided by planting your nodding onions in the freely draining soils and sunny locations they prefer.

Best Uses for Nodding Onions

Heat and drought tolerant, A. cernuum is a terrific choice for the rock garden.

Nodding onions also do well when planted at the fringe of a woodland area, where the plants receive partial shade in the afternoon.

Beds formed around heat absorbent surfaces, like a driveway, can also be a good place to let the plants spread, to add some color to an otherwise inhospitable place.

As a fairly dainty wildflower, this species really looks good when planted en masse, their pendant heads nodding in the summer breeze.

It also proliferates very well from seed, if given the chance. In the cottage or native wildflower garden nodding onion fills in gaps between other perennials, imparting a touch of the wild.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Perennial flowering bulb | Flower/Foliage Color: | Pink, purple, white/ light green |

| Native to: | North America | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 4-9 | Tolerance: | Alkaline soil, clay soil, heat, juglone, part shade |

| Bloom Time: | Summer | Soil Type: | Freely draining soils of all types |

| Exposure: | Full sun, part afternoon shade | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | 3 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | Surface of the soil (seeds), same depth as container (transplants) | Attracts: | Bees, beetles, birds, butterflies, hummingbirds, wasps |

| Spacing: | 4 inches | Uses: | Cottage garden, naturalized areas, rock garden, woodland edge |

| Height: | Up to 30 inches | Order: | Asparagales |

| Spread: | 6 inches | Family: | Amaryllidaceae |

| Water Needs: | Low | Genus: | Allium |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Thrips; downy mildew, white rot | Species: | Cernuum |

Overlooked Easy Keeper

Not many gardeners think of nodding onions when they imagine a spread of beautiful wildflowers.

But these native bulbs are tough as nails and easy to grow. There are few flowers that can compete with nodding onion’s ability to colonize hot, dry places, and fewer still that can put on such a beautiful display under such challenging conditions.

If you’re desperate for summer wildflowers, but lack the rich soils many blooming plants demand, try this little allium on for size in your own garden. You won’t regret it.

Do you grow nodding onions in your garden or have you ever seen them in the wild? Please tell us about your experiences!. Comments and questions are always welcome – we love to hear from you!

And to learn more about growing other types of alliums, check out these guides next: