Moneilema spp.

Cactus longhorn beetles, Moneilema spp., account for 20 of the 35,000 species in the large Cerambycidae or longhorn beetle family.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Black and shiny, they are often confused with beetles from the Eleodes genus in the Tenebrionidae family, such as the malodorous-when-threatened desert stink beetle.

However, unlike these desert counterparts, cactus longhorns cannot fly and do not feed on grasses or burrow into farmers’ crops. These beetles feed solely on cacti.

In this article, we’ll discuss how to recognize and address cactus longhorn beetles in a desert landscape.

Here’s the lineup:

What You’ll Learn

Let’s start with a description for easy recognition.

Identification

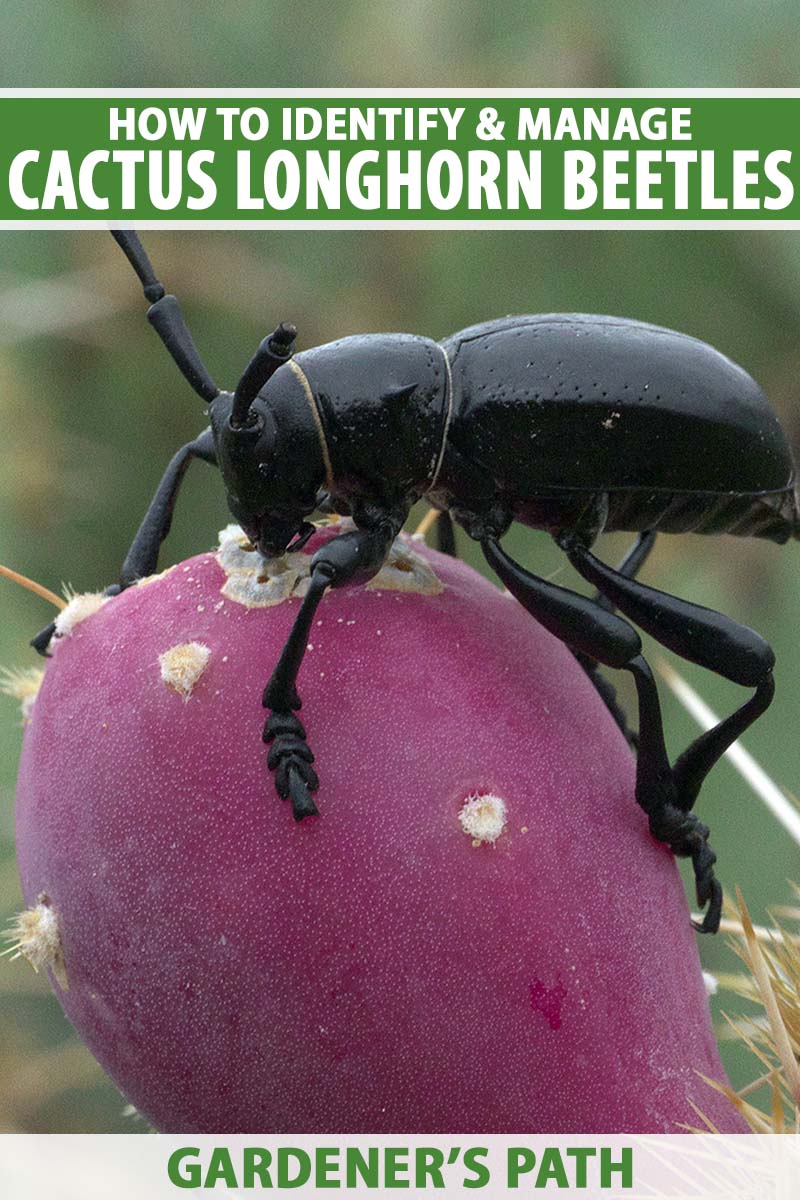

Cactus longhorns have shells that are black or black with white mottling, usually with visible pitting and a glossy sheen.

The bodies of adults measure between 13 and 37 millimeters, or about half an inch to one inch long. They have the typical compound body of beetles consisting of an abdomen, thorax, and head.

The segments are rounded, and the head generally points downward, creating a bent posture as the mandible chews through plant tissue.

Prominent antennae and six splayed legs contribute to the overall dimensions for a formidable appearance.

Unlike some beetles, Moneilema cannot fly. They have fused wings called elytra that run from the uppermost portion of the thorax called the pronotum, down over the lower thorax and abdomen, forming a hard exoskeleton or shell.

The immature larvae are beige and grub-like with brown heads.

The shiny, black cactus longhorn, M. gigas, is a common species in Arizona’s Sonoran Desert and its environs.

In Texas, the spotted type, M. blapsides ssp. ulkei, is prevalent. It’s black mottled with white.

In 1824, American entomologist Thomas Say, an expert in coleopterous insects, aka beetles, classified these, and the other 18 similar species as cactus longhorns.

Host Plants

Insects evolve with plants that provide shelter and food for both their young and the adults of the species.

The “host” plants for Moneilema are two species in the Opuntioideae subfamily of cacti.

Prickly pear cactus is in the Opuntieae tribe and Opuntia genus. Cholla cactus is in the Cylindropuntieae tribe and Cylindropuntia genus. These species have long, sharp spines and clusters of short, barbed bristles called glochid spines.

Opportunistic and ever-evolving, the beetles are sometimes found on little barrel, aka fishhook, cacti. They belong to the Sclerocactus genus.

Moneilema also feed on young saguaro cacti, members of the Carnegiea genus.

And, they may even use flowering plants in the Portulaca genus as hosts.

Knowing which species they prefer can help identify the pests on garden specimens. Understanding their behavior can aid in heading off an infestation.

Life Cycle and Behavior

Cactus longhorns are active from spring through fall, and seasonal monsoon rains are the catalyst that triggers their activity.

Adults live among the sharp spines and feed on the surface of the tenderest foliage. They are nocturnal and crepuscular, or active at twilight.

Females walk on the soil after a night of spring mating, laying their eggs in various places near the base of cacti stems.

When the eggs hatch, larvae emerge and try to burrow into the thick stem flesh. Progress is difficult, as plant juices are released that slow them down.

As they mature, larvae feed voraciously and burrow deeply. They excrete “frass” that mixes with the plant juices, resulting in a black, gooey mass that, in effect, seals their self-bored tunnels behind them.

Larvae change to pupae either in the soil or cactus base. Some species emerge for a second reproductive cycle, while others won’t reappear until the following spring.

Signs of Damage

Because Moneilema aren’t active in the daytime and cactus spines can be very dense, you may not notice them until damage is underway.

Changes in color, consistency, and shape, like yellowing, soft spots, and irregular stem margins, are telltale signs that something is amiss.

Symptoms of adult feeding include surface-level chewing of the tenderest, newest plant foliage.

The activity of larvae creates internal damage, hollowing out stems and causing them to become mere skeletons before collapsing in on themselves.

Wounded plant tissue may rot, inviting a host of opportunistic pathogens to contribute to the death of a plant.

As a resilient group of plants accustomed to desert stressors, you may find a severely damaged cactus attempting to survive by producing “adventitious” roots that seek soil to thrive.

Jumping cholla, Cylindropuntia fulgida, has loose segments that readily detach. In an infestation you may find entire branches lying on the ground, possibly already rooted there.

Without remediation, you may lose entire cacti to these desert menaces.

Infestation Control

In their natural habitat, Moneilema are a delicacy for lizards, skunks, and wood rats. However, attracting wildlife to keep the pest population down may be ineffective and undesirable.

Instead, buy a pair of long-handled tweezers.

This pair from the RSVP International Store and available via Amazon is intended for kitchen use but is equally valued in the garden.

A generous 12-inch length lets you stay well out of the cactus spines, and ribbed silicone tips ensure a firm grip on unwanted pests. Stainless-steel construction promises long-lasting wear.

In the Desert Southwest, monsoon season begins in mid-June, and this is the time to keep a close watch on your plants. Go out in the early evening to catch the adults before mating and egg laying.

Wear gloves not only to avoid the spines but because, while beetles may not be prone to biting people, they have substantial mandibles capable of puncturing skin.

Use the tweezers to grip the pests and drop them into a zippered plastic bag. Zip it and place it inside a second zippered bag.

If you have the stomach for it, you can step on the bags to crush the bugs, but beetles have tough shells, so it may take some effort.

Entomologists who study insects consider freezing a humane way to terminate them.

And while it may take up to a week, depending upon their cold tolerance, you may find it preferable to a stomp fest.

If you choose this method, just lay the double-bagged bugs in the freezer and dispose of them in the trash when all are deceased.

Win the Beetle Battle

Once you know what to look for, you can confidently approach cactus longhorn beetles, despite their intimidating appearance.

Act quickly to remove as many adults as possible. Because the eggs are encased in soil or stem bases, they are difficult to locate and address.

Remember that the adults may do surface damage, but larvae can hollow out entire plants if their feeding goes unchecked.

And, even if you capture and kill adults this year, you’ll want to remain vigilant next year. Pupae that survive the winter will emerge in the spring to start the life cycle again.

Have you dealt with cactus beetles? Please share your knowledge with us in the comments section below.

And to learn more about how to grow cacti and succulents in your garden, check out these guides next: