Salix babylonica

My grandparents’ neighbor had a corkscrew weeping willow tree, and I was convinced it was something out of a fantasy world.

How else do you explain the long, weeping, twisted branches that were equally as useful as a whip to ward off an imaginary charging bull or for imagining you’re walking through an enchanted forest as they drape down from the canopy and over your shoulders?

Only a magical tree could be seemingly immune to the limitations of winter, leafing out when the snow was still a foot deep on the ground. And the gnarled trunk was obviously crafted for a fairytale family of elves.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

I spent hours up in its branches reading books and marveling at how the leaves, so seemingly insignificant individually, combined to make a display that looked like a graceful giant wearing a coat made of green feathers. I’m not the only one captivated by them.

Napoleon took comfort in the shade of a weeping willow while he was exiled, Shakespeare’s Desdemona sings her “Willow Song,” and Claude Monet did a whole series of paintings focused on them.

They appear in works of art, from tombstones to photographs, around the globe and throughout history, and just about everyone I know can paint a fantastical image in their minds when you ask them to picture one.

If you’re captivated by the willow spirit and want to bring one to life in your garden, you’ve come to the right place. Learn more about growing willows in general here.

In this guide, we’ll help you select a weeping willow, plant it, and nurture it into your dream tree.

Here’s what we’re going to go over:

What You’ll Learn

I have to confess that weeping willows lost a little of that magic as I got older, but that was only until I learned that site selection is crucial.

Put one of these in the wrong place and you’re going to be cursing your willow rather than singing its praises.

If you live in USDA Hardiness Zones 5 to 9 and have some room, you’re in luck. Let’s talk about where weeping willows came from before we jump into how to care for them.

Cultivation and History

Weeping willows (Salix babylonica) hail from northern China, but their magic has spread far and wide. They’ve been cultivated in Asia for thousands of years and were traded along the Silk Road.

This species traveled from Syria to England in 1730. Today, weeping willows are wildly popular in Asia, Europe, and the United States.

The specific epithet babylonica comes from Carl Linneaus, a Swedish botanist, who named it because he believed it to be the tree mentioned in the Bible that grows along the rivers of Babylon. But the biblical reference may actually be to poplars, which are closely related.

At one point, S. babylonica and S. matsudana were regarded as different species. Today, they’re generally accepted as synonyms for one another. Having said that, the taxonomic status of this genus is in flux, so it’s always changing.

As willow experts, research geneticists, and horticulturists Frank S. Santamour Jr. and Alice Jacot McArdle wrote in their 1988 paper “Cultivars of Salix babylonica and other Weeping Willows,” “The fact is that most of the “weeping” willows presently cultivated in the United States are not S. babylonica.

Furthermore, if these weeping trees are known by any other name, that name is also probably incorrect.”

That’s because the original willow described by Linnaeus was probably a clone of a clone brought to the Netherlands. This specimen is likely the parent of most willows grown in Europe and North America.

On top of that, there are so many hybrids and cultivars out there that a reclassification might be in order, with the paper’s authors proposing over 30 years ago that we refer to the majority of weeping willows with the cultivar name ‘Babylon’ rather than the species.

At any rate, the trees we’ll discuss here all have extremely similar characteristics, and the characteristics in question that would set them apart from a true S. babylonica are so subtle that the average home gardener wouldn’t have a clue what to look for.

So, what does our weeping willow look like?

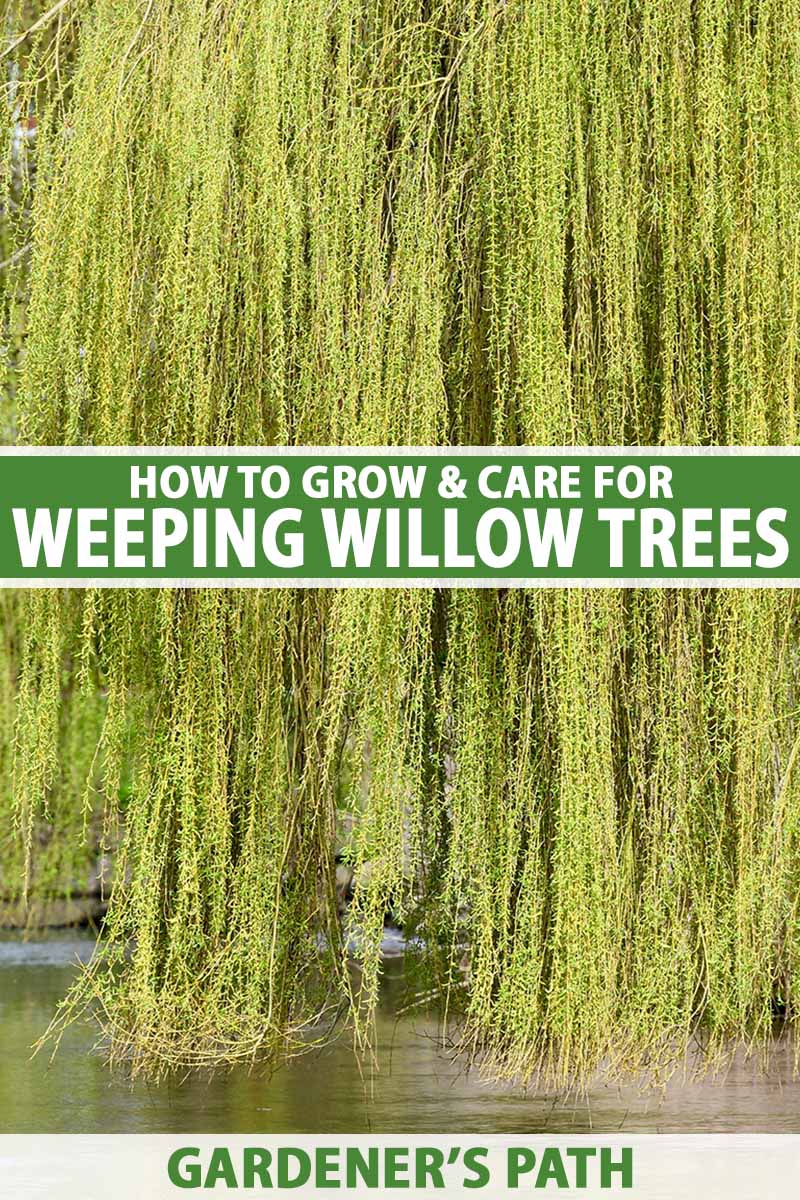

The trunks are covered in rough, gray, deeply-furrowed bark. In the spring, yellow shoots emerge, gradually expanding into long, simple, lanceolate leaves with serrated edges.

The top of each leaf is green and the underside is grayish-green, giving them a rippling appearance when they dance in a breeze. The alternate leaves cling to long, weeping branches with smooth yellow bark.

In the spring, the trees send out inch-long yellow catkins covered in tiny flowers. These then form hard, dry capsules covered in a fine fuzz.

Weeping willows have long been a symbol of sadness and mourning. Good thing no one told me that when I was daydreaming in a crotch of branches high above the ground.

Monet’s 10 willow portraits were his reaction to the sorrow in the aftermath of World War I. Desdemona’s “Willow Song” is one of sorrow and death. But the common 1800s willow motif on gravemarkers and tombstones isn’t just one of mourning.

People also see it as a promise of rebirth and new beginnings. If you’ve ever seen how readily the young branches can create a new, thriving specimen, it’s easy to understand why.

In Chinese Buddhism, the bodhisattva Guan Yin is often depicted as or with a willow branch, which is thought to represent resilience.

Sadly, weeping willows are short-lived. It’s not uncommon for them to die after just 30 years or so. That said, my grandparents’ neighbor’s willow is still going after 50 years, so it’s possible for them to live longer.

This and all members of the Salix genus attract some welcome pollinators when they bloom in the spring, such as willow (Andrena andrenoides), eastern willow (A. bisalicis), red-bellied (A. erythrogaster), cold (A. frigida), tufted (A. illinoiensis), Macoupin County (A. macoupinensis), Maria (A. mariae), A. nida, black (A. nigrae), small willow (A. salictaria), and Wellesley miner bees (A. wellesleyana).

If you grow crops like blueberries, apples, and huckleberries, you can’t find better pollinators. Plant a weeping willow nearby and watch the spring pollinator show unfold.

Weeping willows grow fast, up to four feet per year, but the new growth is weak and breaks easily. Trees will rapidly send out replacement branches when they break or if they are pruned.

Weeping Willow Propagation

If you have access to a weeping willow that you can take a few cuttings from, you’re in luck.

This tree reproduces enthusiastically that way. You can also pick up a youngster at most nurseries.

Let’s look at propagating cuttings first.

From Cuttings

I’ve never worked with a plant that’s easier to grow from stem cuttings. And it’s not that I’m some propagation genius! People actually make homemade root starter using willows.

If you’ve ever bought rooting hormone, it probably contained a synthetic form of indolebutyric acid. That acid occurs naturally in Salix species. In other words, they make their own rooting hormone, so they’re ready to root without any extra help.

Wait for a day with temperatures above freezing in February or March when the branches are starting to show signs of life, but they haven’t budded out yet.

Grab a couple of 18-inch lengths of live branches that are around the same diameter as a pencil. Give them a gentle bend to see if they’re alive. Don’t take any that snap rather than bending.

Bundle the branches together and tie them with a piece of string. Place them in a large plastic bag along with a moistened sponge or a wad of wetted sphagnum moss.

Place this in the refrigerator for four weeks. Keep an eye on the moistened material to ensure that it doesn’t dry out or that any mold is forming.

If you see mold, wipe it off using soapy water or remove the bundle and let it air out for a few hours. Place it in a new, fresh bag with a fresh sponge or moss.

Once the sticks have chilled for a month and the soil can be worked outside, insert each cutting into the soil so that about a third of it is below the soil line.

Make sure to take into account the ultimate size of your tree. Don’t plant cuttings within 20 feet of anything you don’t want smothered in willow branches or invaded by roots.

Keep the soil moist. Don’t let it dry out.

Give it a few weeks, and the cuttings should develop green, leafy growth and roots underground.

This is the method that’s most likely to be successful.

But you can take a cutting at any time of year that the soil can be worked as long as you’re able to keep it watered, and you can skip the cooling period. Just take your cutting, stick it in the ground, and keep the soil moist.

This simpler method may impact your chances of success, but I’ve honestly never had one fail on me yet.

From Potted Plants or Transplants

Just as rooting cuttings couldn’t be easier, neither could planting a potted weeping willow.

In the spring or fall, so long as you’ve found the right spot, far, far away from irrigation or sewage lines, dig a hole about the same size as the growing container.

Don’t worry about digging a larger hole and backfilling it with amended soil, as you often do with other species. The roots of willows need no extra encouragement.

In fact, once your plant is in the ground, it should take off fairly quickly. No sleep, creep, leap for weeping willow trees.

Keep the soil moist as your weeping willow establishes itself. For at least the first year, water any time the top inch of soil dries out.

After the first year, allow the top few inches to dry out before watering until the tree has been in the ground for five years. Then, water as described below.

How to Grow Weeping Willows

Given at least four hours of sunlight per day, you can expect your weeping willow to grow up to two feet per year until it reaches its mature height of 40 feet.

Some can even grow up to 80 feet in ideal conditions. They typically grow as wide as they do tall, or just slightly less wide.

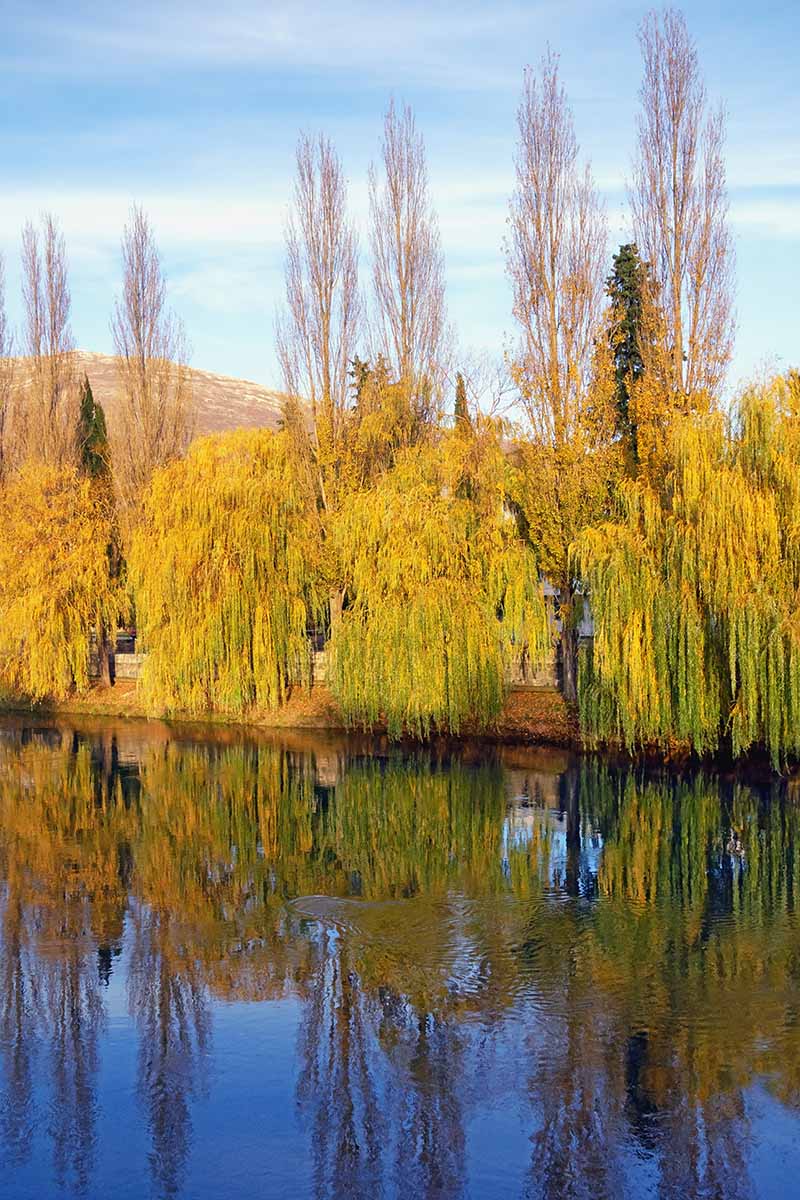

These are thirsty trees. They do best when placed near a body of water that they can stretch their roots into.

I had one growing next to my canal, and it was blissfully happy. I mean, it’s not for nothing that you often see weeping willows growing next to placid ponds.

They can tolerate short periods of drought, but they can’t go long without heavy, regular moisture.

If you live in an arid area without groundwater within a dozen feet of the surface, unless you’re willing to irrigate regularly and for a long while each time, don’t plant weeping willows.

A young willow will be perfectly happy with the water provided through a sprinkling system, but as they age, those roots start looking for a deeper, more abundant source of moisture.

Sprinklers just won’t cut it unless you water long enough that the moisture reaches several feet down. That much moisture will likely drown your lawn.

When they don’t receive the water they need, they resort to taking matters into their own hands.

Willows have notoriously destructive roots and they can spread twice as wide as the canopy. I wonder how many septic lines have been breached by thirsty trees.

My brother, who is a plumber, says that he assumes when someone has a willow in their yard that’s anywhere near sewer, water supply, or irrigation, they will have a breach somewhere.

Plant them far away from pools, irrigation lines, sewage lines, water supplies, wells, and septic systems.

If your tree doesn’t manage to find a water source nearby and you don’t provide irrigation, it will drop its leaves.

On the other hand, if you have an area where moisture pools regularly, this tree will soak it up like a champ.

As we mentioned, young weeping willows need consistent moisture. The soil should feel like a sponge that you’ve wrung out thoroughly over the sink.

Once it becomes established after five years or so, you can allow the top three or four inches of soil to dry out before you irrigate.

When you water, make sure it’s long and deep rather than at the surface in order to encourage deep root growth.

Seeking water isn’t the only reason to be smart about where you plant these trees. The roots will also lift out of the soil, cracking sidewalks, lifting driveways, and making mowing an annoying chore.

Don’t even think about planting one next to a driveway or sidewalk.

As if all that weren’t enough, weeping willows can be extremely messy. As we mentioned, they grow fast, up to four feet a year, but the wood that grows is weak. That weak wood extends to the weeping branches, which can drop by the dozens in a storm.

As lovely as it is, this really is a tree for a remote spot near a river or lake where it can spread out without becoming a nuisance.

If you’re picturing a weeping willow for your tiny backyard next to your patio, you might want to adjust that picture to include a weeping Japanese maple or a redbud instead.

These trees prefer slightly acidic soil, though they aren’t fussy. Anything from 4.0 to 8.0 is fine. They can also tolerate slightly sandy or slightly clay soil, though loam is preferred.

Once the tree has matured, it doesn’t need feeding. Young weeping willows benefit from a mild, tree formulated fertilizer. Apply it in the spring after the catkins have faded.

Any deciduous tree fertilizer will work, but I’m always singing the praises of the fertilizers made by Down to Earth. They’re all natural and come in compostable boxes.

Down to Earth Tree & Shrub Fertilizer

Their Tree & Shrub mix also contains mycorrhizal fungi to help the tree establish a healthy root system. Grab five or 25 pounds at Arbico Organics.

Growing Tips

- Plant away from pools, sewage lines, and water supplies.

- Keep soil moist while trees are young.

- Plant in partial to full sun.

Pruning and Maintenance

As we mentioned, one of the downsides to all that fast growth is that the branches tend to be weak. Ice, wind, and heavy snow will regularly take a toll on this tree.

You will need to get in there with a tree pruner and cut any broken branches back to the stem or trunk.

You should also prune regularly to maintain the tree and prevent breakage.

In late winter or early spring, pick up those clean pruners or a saw. Remove anything that is dead, dying, diseased, or broken, making your cuts below the damage.

Then, you can remove anything you don’t like the look of to further shape the tree, if you want.

You don’t have to prune an older specimen, but it can provide some shape and definition if you feel that it has gotten a bit out of hand.

Young weeping willows should be pruned to maintain a central leader. They sometimes like to branch out and develop multiple trunks, but if they do, they’ll be prone to breakage at the crotches. Sadly, that happened to one of my trees.

One brutal winter, the weight proved to be too much for my tree and it broke at the joint between two of the three main branches.

Luckily, it survived after we shaped it back up, but it was a shadow of its former self. Or rather, a lopsided specimen of its former self – it was more of a half circle than a rounded umbrella.

These trees lend themselves to pollarding if that’s something you’re interested in. Pollarding is the practice of cutting the main branches back so they extend just slightly out of the trunk.

Pollarding is not topping. Topping is cutting most of the canopy back to the trunk. Pollarding requires more finesse and shaping.

Do not give in to the temptation to top these trees. I know it seems like an easy way to reduce their size and regenerate growth, but it weakens the tree overall.

If you pollard, know that your tree will send up all kinds of new sprouts, so they won’t maintain that classic pollarded look for long.

Cultivars to Select

If you dream of having a weeping willow but worry about its bad reputation when it comes to disease issues, you might consider a plant in the Sepulcralis group.

These are hybrids of S. babylonica and S. alba, and they are more cold tolerant than the S. babylonica species.

S. × sepulcralis ‘Chrysocoma’ is one of the most popular weeping willows out there.

Most of the time, you’ll find plants described as the species (until scientists agree on a new classification) for sale unless you check out specialty nurseries.

For instance, you can pick up a live species weeping willow that’s five to six or six to seven feet tall at Fast Growing Trees.

When it comes to finding true S. babylonica cultivars, it’s the Wild West out there.

There are many that are described as a babylonica cultivar, but experts believe they might be better classified as a different species, as we discussed above.

The following are currently believed to be true S. babylonica cultivars or varieties:

Aurea

‘Aurea’ looks in all ways like the species except the young wood of the weeping branches is brilliant yellow. It grows to the same height with the same size and color of foliage.

Crispa

This cultivar is one of the most interesting ones out there, in my opinion. The silver and green leaves curl around in a circle, giving them a distinct resemblance to a ram’s horns.

The tree will ultimately obtain the familiar rounded shape, but it starts out upright before gently weeping. When fully grown, it reaches a height of about 40 feet.

Corkscrew

Corkscrew willows, S. babylonica var. matsudana ‘Tortuosa,’ are smaller than the species, rarely growing taller than about 30 feet.

The name comes from the twisting, contorted stems that look beautiful tucked into a floral arrangement or on their own in a vase.

Golden Curls

Introduced in 1976 by Charles Beardsley of Geneva, Ohio, ‘Golden Curls’ has golden-green leaves with a rippling margin on yellow branches that transition to bronze as they age.

It grows to about 30 feet tall when mature and, like the rest of its weeping friends, it’s a fast grower.

Scarlet Curls

Previously classified as S. matsudana, this babylonica cultivar is named for its wood, which has a red hue when young.

As it ages, the wood matures to the familiar gray, while the spiraling stems retain their scarlet hue until they age into a bright yellow.

The leaves have wavy, curled edges, adding yet another element of interest. If you like taking willow branch cuttings for display in the home, this one should be at the top of your list.

Managing Pests and Disease

Weeping willows don’t live for a long time. That’s part of the reason why they have a reputation in some areas for being prone to problems.

The truth is, if you get 70 years out of yours, you did exceptionally well. Something more like 30 to 50 years is more typical. That’s just their usual lifespan.

Younger plants may be suffering from pests or disease if they begin to look sickly.

Before we explore the many insects and disease issues that might strike your weeping willows, let’s look at another potential problem: deer.

Deer

Deer won’t hesitate to grab a bite of willow as they pass through your yard. Left unchecked, they can kill a young tree.

Every time I tried to start a young tree in an area where deer were frequent visitors, it would vanish after a week or two, a sad stump the only thing left behind.

I finally gave in and protected my youngsters.

Surround young trees with a fence until they’re large enough to withstand browsing. Don’t worry, it doesn’t take too long. Most trees are big enough to hold their own in about five years. Our guide has more tips on deterring deer.

Insects

Insects are not usually the primary concern when growing weeping willows. They can cause some damage to young trees, but older trees usually weather an infestation just fine.

While they don’t cause any real damage, willows are a primary host of spongy moths (Lymantria dispar dispar), which you don’t want around. They’re also a favorite of fall webworms, which won’t harm the tree, but can be ugly.

Aphids

Giant willow aphids (Tuberolachnus salignus) are extremely common, and the damage they cause ranges from no big deal to devastating.

If you’ve seen aphids before, these are similar, but bigger, up to six millimeters in length. They also have a row of spots and a raised cone on their backs.

That raised cone looks a lot like a shark fin, which is why we call them shark aphids. And as with sharks, if you see one moving down the branches of your tree, the theme from “Jaws” should certainly start playing in your head.

They use their piercing-sucking mouthparts to feed on the young growth of the tree, and they can cluster in huge groups of thousands of individuals. As you might imagine, that can cause a lot of damage, stunting growth and killing branches.

They typically start their activity in the heat of the summer. The females reproduce asexually, also known as parthenogenetically. Each one can produce 30 nymphs at a time, and they have several batches each year.

They stick around throughout the winter, impervious to cold temperatures, when they begin the cycle again.

Parasitic wasps, ladybugs, hoverfly maggots, and lacewings will all feed on these pests, which can help keep the situation under control when they’re active. But as the weather turns, the aphids are left unchecked.

To help the beneficial insect predators out, use insecticidal soap every other week for as long as you see the pests.

You probably won’t be able to reach all parts of the tree, but so long as you keep covering as much as you can, populations will be kept under control enough not to harm your willow.

Borers

Cottonwood borers (Plectrodera scalator) and carpenter worms (Prionoxystus robiniae) bore through the bark and wood of the trees, causing scarring and girdling of smaller branches.

The first thing most people notice when either of these borers are present is frass. That’s the excrement along with the sawdust that the pest leaves behind as it tunnels into the tree.

You might also notice dark sap spots and holes in the trunk.

You might be able to spot the adults, a beetle in the case of cottonwood borers and a moth in the case of carpenter worms, but it’s the larvae that do all the damage.

Carpenter worms can grow up to three inches long and cottonwood borers about half that.

Healthy trees can usually withstand some damage, though it does leave the tree open to disease. Still, you don’t want these pests hanging out.

There are two things to do in order to get rid of them:

First, spray your tree with an insecticide to kill the adults so that no new larvae are hatching. Then, grab yourself some beneficial nematodes. Either Steinernema feltiae or S. carpocapsae (or both) will do.

Mix the nematodes with water. Typically, you want one million nematodes per gallon. Put the nematode water in a squeeze bottle or oilcan. Anything that has a small nozzle and allows you to squeeze out the water will work.

Then, clear out each hole of any debris and squeeze the water into the holes until it starts coming back out of the hole or out a nearby entrance. Seal the holes up with putty or wax. Do this until all the holes you can reach are filled.

You might need to do this a few times before all the larvae will be gone. If so, wait two weeks between treatments. You’ll know they’re still there if an opening you sealed has been popped open.

NemAttack Beneficial Nematodes

It’s amazing how effective beneficial nematodes can be. If you don’t already have some in your gardening toolkit, grab five, ten, 50, 250, or 500 million at Arbico Organics.

Scale

There are lots of scale insects that feed on willows, including greedy (Hemiberlesia rapax), latania (Hemiberlesia lataniae), oystershell (Lepidosaphes ulmi), San Jose (Quadraspidiotus perniciosus), brown (Coccus hesperidum), and cottony maple scale (Pulvinaria innumerabilis).

Regardless of the type, they feed on willows with their piercing-sucking mouthparts, draining the sap from the plant. They don’t typically cause a lot of problems on a mature weeping willow, but they can harm young trees.

These don’t look like your typical pests. Clustering on young branches, they tend to look like a lumpy, bumpy symptom of disease instead, since they don’t move much.

Visit our guide to learn how to identify and control them scale, but note that control isn’t always necessary.

Unless your tree has yellowing leaves and isn’t growing as quickly as you expect, you might just tolerate them.

Disease

Weeping willows have a reputation for being susceptible to disease problems, and this is not entirely undeserved.

There are a few diseases that can positively wreak havoc with your trees, and some of them are distressingly common.

Fortunately, this tree is resistant to the willow scourge, black canker, caused by Botryosphaeria dothidea and Physalospora miyabeana fungi (syn. Glomerella miyabeana). It’s also resistant to verticillium.

Powdery mildew can cause a white coating to form on the leaves, but it’s never a big enough deal to warrant treatment. But these ailments might cause more of a problem:

Anthracnose

Anthracnose is caused by one of those pathogens that just loves nice and cool, wet weather. If you typically experience this in the spring or you have a particularly wet, cold spring one year, anthracnose is likely not far away.

The fungus Marssonina salicicola initially causes purplish-brown spots on the leaves, usually along the veins. These can merge together as they grow, causing the foliage to drop. Typically, the outer leaves will remain while the interior leaves drop like flies.

One day your tree is filling out, starting to look lush and full, and the next, the crown starts to look awfully thin.

As things get worse, new shoots start dying and cankers start to develop on the twigs and branches. These might die back as well.

The first step is to prune off all symptomatic branches. I know, that might mean your tree will look like it got quite the haircut. Don’t worry, willows are good at growing back bigger and better than before.

Then, spray your tree every two weeks until the weather turns warm and dry. There are lots of products that you can use to kill the fungus that causes this disease.

Copper and sulfur sprays work well. So does a product called Mycostop, which harnesses the power of a type of bacteria found in sphagnum moss to kill bad pathogens.

I use it to treat pretty much every fungal disease that comes my way and it hasn’t disappointed me yet.

Mycosop is available at Arbico Organics in five- or 25-gram packets. I will caution you that once you open the packet, you need to use the product up quickly. It doesn’t store well.

Spray your tree the moment you see symptoms and keep at it until that summer weather kicks in.

Blight or Scab

Blight, also known as scab, is fairly common in the eastern US and parts of the Pacific Northwest, and it is easy to identify.

The fungus Venturia saliciperda infects trees during wet spring weather. Once it does, the young twigs and leaves will develop dark brown blotches. The tips of the twigs will die back as the fungus enters the petioles.

Later, the blotches will develop a lighter brown spore coating and the infected leaves will drop from the tree.

Weeping willows aren’t as susceptible to this disease as other Salix species, but that doesn’t mean it can’t happen.

If you catch it in the first year, it’s easy to treat and help your tree to recover. But if it’s allowed to infect your tree for several years, this weakens the tree, inviting other fungi like those that cause black canker, which doesn’t usually impact weeping willows.

Infection also leaves the tree open to pest damage and drought stress.

Treatment involves spraying the tree every two weeks, beginning when the leaves bud out and continuing for two months.

Preventative treatment and treatment just as the spores are developing is crucial.

Use a product like Serenade ASO, which is a biofungicide that uses Bacillus subtilis strain QST 713, to protect your plants. Apply it both to the foliage and to the soil.

Arbico Organics carries Serenade ASO in 2.5-gallon containers.

In addition to or instead of this, you can also use a product that contains citric acid, which will kill the fungi on contact rather than creating a protective barrier, as B. subtilis does.

You should wait until the first product dries before applying the second one, but you can apply them on the same day.

Arbico Organics carries a product called Procidic, which contains citric acid. It’s available in 32-ounce ready to use bottles, as well as 16-ounce or gallon-size concentrate.

Crown Gall

Crown gall, caused by the bacteria Rhizobium radiobacter, is a common problem on willows.

It causes tumor-like growths that limit the movement of water through the tree. This results in stunted growth, yellowing leaves, and dying shoots.

If a tumor grows on the trunk or main stems, it can kill the tree.

The bacteria often enters through wounds in the wood, even from something as small as a hole left by a borer.

An established tree might look a little funky here and there due to crown gall, but these can be left in the landscape. Young trees, however, should be removed. There is no known cure once a tree is infected.

If you have to pull a tree, don’t plant anything else there that is susceptible to crown gall for at least three years.

Leaf Spot

As the name suggests, this disease causes the leaves to form irregular brown spots. These spots usually have feathered, purple margins. As the disease progresses, the leaves turn yellow and drop from the tree.

Pseudocercospora salicina causes this disease. Left unchecked and in the right environment, the fungus will cause branches to die.

Grab any of the same fungicides described to treat anthracnose above, like copper or sulfur, or another broad fungicide, and get to work the moment you see spots.

Spray your tree once every two weeks until new foliage emerges and remains symptom free.

Best Uses for Weeping Willows

This isn’t a tree for planting next to your small patio or deck. But you can’t find a better specimen for filling in a large area, especially if you have a body of water nearby.

If you love the look of a living fence, there is no better species than a willow, weeping or otherwise. They’re also incredible when used for bonsai and they grow quickly so you can enjoy the results sooner than you can with other species.

Weeping willows are also invaluable if you like to use cuttings to decorate your home.

A large vase on the ground filled with six-foot-tall corkscrew branches makes a huge statement. Or snag some of the budding branches in the spring for an early display.

A lot of people plant weeping willows in the middle of a stretch of lawn, and that’s certainly a pretty option.

I think they also look beautiful with shade-loving plants grouped underneath. Think things like hosta, vinca, astilbe, and ferns.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Deciduous tree | Flower/Foliage Color: | Cream, yellow/green |

| Native to: | China | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 5-9 | Tolerance: | Some drought |

| Bloom Time/Season: | Spring blossoms | Soil Type: | Moderately sandy, loamy, moderately clay |

| Exposure: | Partial to full sun | Soil pH: | 4.0-8.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | Up to 20 years | Soil Drainage: | Moderately well-draining |

| Spacing: | 20 feet | Attracts: | Andrena miner bees; mourning cloak (Nymphalis antiopa), red-spotted purple (Limenitis arthemis), and viceroy (Limenitis archippus) butterflies |

| Planting Depth: | Depth of growing container (transplants) | Companion Planting: | Astilbe, hostas, ferns, vinca |

| Height: | Up to 80 feet | Avoid Planting With: | Sun-loving plants |

| Spread: | Up to 80 feet | Uses: | Bonsai, specimen |

| Growth Rate: | Fast | Family: | Salicaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Salix |

| Common Pests and Disease: | Deer; aphids, borers, scale; Anthracnose, blight, crown gall, leaf spot, powdery mildew | Species: | Babylonica |

Make Your Garden into a Fairytale

Despite their bad reputation, I can totally understand why people would want one of these magnificent trees.

They’re completely unlike anything else. It’s no wonder the weeping willow figures so heavily in our lore and our collective imagination.

What’s your first memory of one of these trees? Was it from a Tolkien book? The Disney “Pocahontas” movie?

I’d love to hear about how you fell in love with these trees in the comments. And if you have any questions about caring for your tree, put them in the comments, too.

Want to add some other landscape trees to your garden? Read these guides next: