Polypodiopsida

Have you ever heard of pteridomania? If you’re reading this article, you might be suffering from it and not even realize.

Pteridomania is defined as an obsession with ferns. Don’t worry, I’m suffering from it, too.

I’ve got all kinds of species growing indoors and out. I can’t help it, they’re such fascinating and beautiful plants.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Perhaps you’ve mastered growing plants in the Polypodiopsida class outdoors and you’re looking for help to make the same magic happen indoors. Or maybe you’re new to the whole process. Either way, we’ve got your back.

To help you turn your indoor space into a magical fern paradise, here’s what’s coming in this guide:

What You’ll Learn

Fun fact: ferns grow on every continent except Antarctica – though there are fern fossils on Antarctica.

There are species that grow in every USDA Hardiness Zone, from 1a to 13b. These plants have had centuries to adapt to even the harshest environments.

That means there are many species that have adapted to the exact sort of conditions we have in our homes, namely: warm, low light, and moderate humidity.

Cultivation and History

Ferns are plants in the botanical class Polypodiopsida, comprised of about 10,500 existing species – and a lot more that are now extinct.

Scientists aren’t sure exactly how many species exist, and some estimates suggest that there could be 15,000 species out there.

These are truly ancient plants. While many of the species that we see around us evolved relatively recently on the timeline of planet Earth, ferns were hanging out with the dinosaurs and even well before that.

They first developed during the Devonian period, which began about 420 million years ago. This is the period when fishes really diversified, and the amphibians that would eventually be the origin of all land mammals evolved.

Meanwhile, on land, the supercontinent comprising North America, Europe, and Greenland, and the southern landmass made up of modern South America, Africa, India, Australia, and Antarctica, were covered in ferns.

This is, in part, thanks to the fact that the climate was warmer than it is today, which ferns typically prefer. These plants really diversified during the Cretaceous period.

Fast forward just a few hundred millennia, and through several mass extinction events, and you arrive in the modern era with humans and ferns coexisting.

Growing ferns as houseplants became popular during the Victorian era. People were obsessed with houseplants in general, and ferns were high on that list. Pteridomania took hold of England and the US around the 1840s and lasted for 50 years.

A lot of people chose to grow their plants in Wardian cases, the Victorian version of a terrarium, during this period because the plants failed to thrive in the polluted, dry conditions of the city.

Not only was practically everyone growing the plants in their homes and gardens, but the motif was plastered on anything and everything. People pressed the leaves to display in their homes, and many believed that collecting ferns improved their virility and mental health.

Knowing what we do about the impact of nature on human well-being, that last part might have some truth to it, especially since collecting these plants required people to get outside and explore the countryside.

Broadly speaking, most of the ferns we grow in our homes today are tropical species rather than those you’ll find in the wilds of the northern latitudes. That’s because species from temperate zones don’t thrive in the same conditions that you find inside the average home.

Many of these tropical ferns are epiphytes, which means they grow attached to other plants.

Fern Propagation

Propagating ferns might seem intimidating as they aren’t like many other plants with their flowers and seeds that you can pluck and sow in the soil.

But they’re not so challenging – most can be reproduced through division, plantlets, stipe (or stem) cuttings, or by propagating the spores.

The spore process is lengthy and requires some special equipment, but the others aren’t much different from propagating any other houseplant. If you’ve ever divided a plant that was outgrowing its pot, then you’re already familiar with the process.

The same goes for stipe cuttings, which are similar to stem cuttings. While they’re easy to accomplish, this method doesn’t work on all species.

Regardless of which method appeals to you, our guide to propagating ferns has everything you need to know for success.

How to Grow Ferns

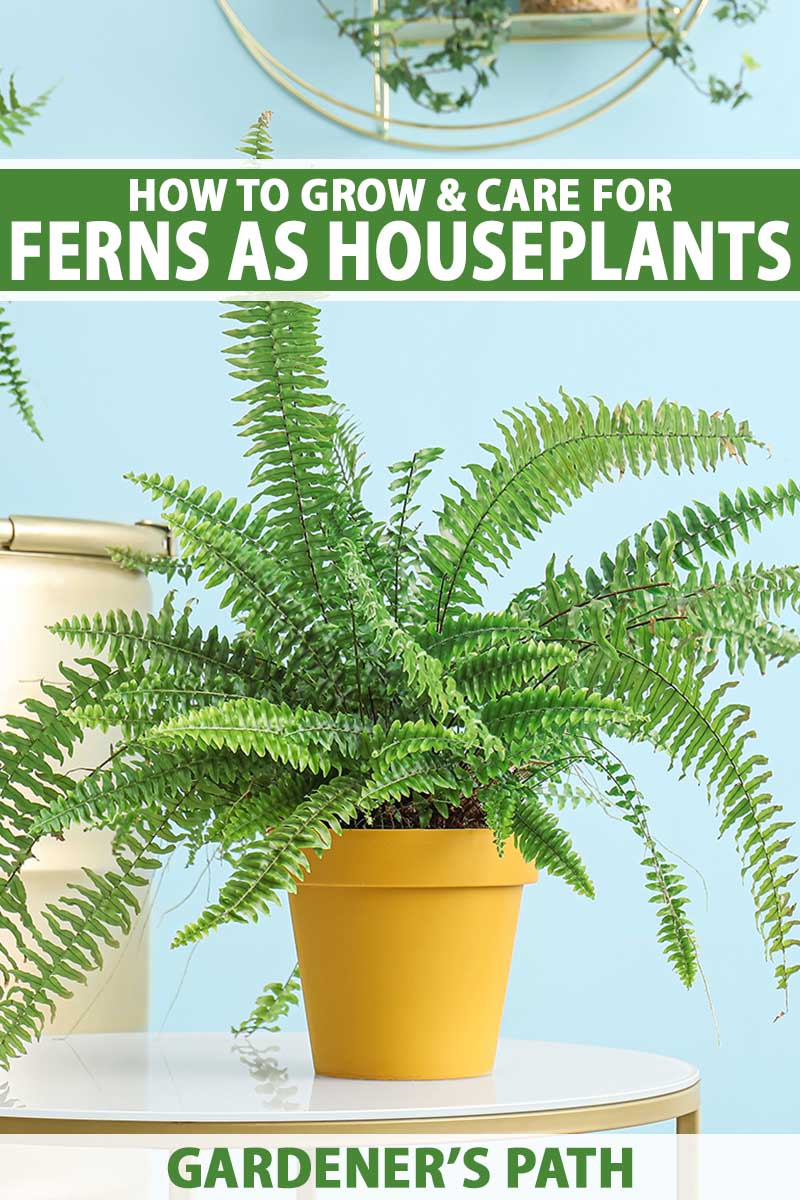

Caring for a fern indoors depends on which type you are growing.

A staghorn fern (Platycerium spp.) is pretty happy indoors, but as I mentioned, many of our favorite garden varieties struggle inside.

Maidenhairs (Adiantum spp.) can grow indoors, but they are temperamental. Boston ferns (Nephrolepis exaltata), on the other hand, do well indoors.

In general, if a species grows in cool climates or if it has frilly, feathery foliage, it will be more difficult to grow as a houseplant. Species that are native to warm, tropical areas, which often have more solid fronds, do better. But there are exceptions.

Most species need bright, indirect light, consistently moist potting medium, and moderate humidity.

Most temperate climate ferns need what we would call “dappled” sunlight, which is the kind of light you get underneath the canopy of a tree.

Indoors, that translates to a spot near a west- or south-facing window covered in a sheer curtain. Or maybe you have an east- or south-facing window with a big evergreen tree right outside that blocks the sun’s rays.

Take some time to research the particular species that you’re growing – or want to grow – and the conditions in its natural habitat. You might find that you have a species that likes to dry out a bit and requires direct morning light.

Broadly, you can assume that a general potting mix will be fine.

Something like De La Tank’s House Plant mix, with its combination of compost, coconut coir, pumice, and natural fertilizer would be ideal.

Bring some home from Arbico Organics in one-, eight-, or 16-quart bags.

Container choice is important. You want something that both retains moisture and is well-draining.

Terra cotta may look nice, but it dries out pretty quickly. You’re certainly welcome to use it, but be extra diligent about monitoring the moisture level.

Better yet, choose glazed clay or stone. Whatever material you choose, the container needs to have drainage. If you find a pot you love that lacks drainage holes, that’s fine. Just keep the plant in a plastic grower’s pot and put it inside the decorative pot.

You could also drill holes in the decorative pot, but if you aren’t experienced with the process, don’t attempt it on a container that you cherish.

The container should be at least a few inches wider than the existing pot the plant is growing in. Remember, the base of the plant is different than the width of the fronds. The fronds tend to spread out much wider than the base.

You should also be sure the pot is heavy enough to hold the plant. You don’t want to be scooping up dirt and broken fronds if the dogs get a bit too excited and knock over your ferns!

When you water, be sure to empty the catchment tray or container about 30 minutes after watering. These plants can’t stand soggy roots, with few exceptions.

Different species vary wildly in their water preferences, but most need soil that is moist but not soggy. Water when just the top of the soil dries out.

Fertilize your plants once a month during the spring and summer with a mild, balanced food.

A product with an NPK around 3-3-3 or 5-5-5 works well. Even better if you can find something higher in nitrogen than phosphorus and potassium.

For instance, Arber’s Plant Food has an NPK of 3-2-1 and a subtle rosemary fragrance that smells much better than your typical fertilizer.

Grab a 16-ounce bottle at Arbico Organics.

Growing Tips

- Familiarize yourself with the needs of the species you’re growing.

- Most need bright, indirect light and consistently moist soil.

- Fertilize once a month during the spring and summer.

- Choose a pot large and heavy enough to support the plant.

Pruning and Maintenance

There’s no need to prune ferns except to remove any yellow, damaged, dead, or dying fronds. Otherwise, the only maintenance you’ll need to do is repotting or dividing the plants as they mature.

Many species don’t mind being a little root bound, but they eventually need to move up to a larger pot, or you need to divide them to provide more space.

Repotting and dividing also gives you the opportunity to replace the soil, which can become hydrophobic or depleted.

The first step is to remove the plant from the existing container and dump out any excess soil. Then, brush the soil away from the roots. Loosen up the roots.

If you’re upgrading the pot size, place the plant into the new container and fill in around the roots with fresh, clean potting soil. The plant should be sitting about the same height that it was in the existing pot.

If you’re dividing the plant, use a clean pair of scissors or pruners to cut through the roots and petioles to create two or more sections.

Replant one section in the previous pot with fresh soil and either dispose of or give away the other section, or plant it in its own container.

Fern Species to Select

Success with growing ferns indoors starts with picking the best species for your needs and skill level. If you want a fern that grows well indoors with a minimum of pampering, you have lots of options.

There are also some choices for those looking for more of a challenge. We’ll cover a few of both here:

Bird’s Nest

Bird’s nest ferns (Asplenium nidus) are epiphytes that hail from southeast Asia, Hawaii, and parts of Australia.

Out in the wild, the leaves look much like those of banana plants, but in the home, they stay smaller. The leaves are strappy and glossy with wavy margins.

These plants need bright, indirect light, moist potting medium, and at least 50 percent humidity.

Given those conditions, they make beautiful houseplants that aren’t too fussy. Plus, they aren’t toxic to pets with curious mouths.

Bring this little birdie home from Planting Tree for an instant tropical vibe.

Learn more about these pretty plants here.

Boston

Boston fern (Nephrolepis exaltata ‘Bostoniensis’) is a type of sword fern with alternate leaflets that bring that classic fern shape into the home.

Most people find this type easy to care for indoors. I say “most people” because I have absolutely no luck with them. Every time I bring one into my home, it takes a look around and says to itself, “I’d rather die than live here.”

I try not to take it personally, though it’s definitely a “me” thing. Everyone I know who has a Boston fern seems to think it’s the easiest thing to grow ever.

It’s just one of those curiosities, especially since I have mastered indoor maidenhair fern cultivation, and legend has it that only the chosen few can do that.

All that aside, so long as you aren’t me, these plants are perfectly happy when provided with medium bright light, consistent moisture, and high humidity of around 80 percent.

Being that they hail from warm forests in South America and the West Indies, all that should come as no surprise.

Head over to Nature Hills Nursery to bring one home to your place. Just keep it away from mine.

Learn more about growing Boston ferns in our guide.

Button

I just know the person who gave Pellaea rotundifolia its common name of “button fern” was thinking it was as cute as a button. I mean, the little, rounded pinnae are pretty adorable.

This evergreen Australian and New Zealand native prefers to dry out a bit between waterings, so it’s perfect for those who forget to bring out the watering can now and then.

It’s also tolerant of drier climates, and will do fine in humidity between 20 to 60 percent.

This species likes low light and looks particularly nice in a hanging basket thanks to its pendulous growth habit.

Home Depot carries these plants in a four-pack of four-inch growers pots.

Holly

Holly, Japanese, or house holly fern (Cyrtomium falcatum) originated in southern Asia, where it grows on rocky hillsides, cliffs, and river banks. It gets its common name from the holly-like foliage.

In the comfort of your home or workplace, it needs bright, indirect light and temperatures above 50°F. It’s not too particular about humidity but needs consistently moist soil.

Kangaroo

Hailing from Australia and New Zealand, the kangaroo fern (Phymatosorus diversifolius) sports large, dark green leaves and a cascading growth habit.

It reaches a mature height of one foot tall, but can spread two to four feet.

This epiphytic plant enjoys temperatures of 60 to 70°F and humidity of at least 75 percent. Provide indirect light and consistently moist – but not waterlogged – soil.

You can find plants in six-inch pots available from California Tropicals via Amazon.

Learn more about cultivating kangaroo ferns here.

Kimberly Queen

The beautiful sword-shaped fronds of Nephrolepis obliterata, aka Kimberley queen, scream classic fern.

Hailing from Australia, this plant likes consistently moist soil, indirect or morning sun, and humidity between 60 and 70 percent.

You can allow the top inch or so of the soil to dry out, making this a nice option for those who struggle to remember to water.

Watch out, it can grow three feet tall and wide if you give it a large enough pot!

Lemon Button

The lemon button fern (Nephrolepis cordifolia ‘Duffii’) is a dwarf cultivar of the fishbone or tuberous sword fern, N. cordifolia.

Featuring short, yellowish-green, button-shaped foliage, this compact plant is just 12 inches tall and wide, making it ideal for smaller-space placements.

Provide a spot with bright, indirect light, temperatures of between 60 and 80°F, with around 70 percent humidity. Water when the top of the soil is dry to the touch.

You can find plants in four-inch pots available from Hirt’s Gardens via Amazon.

Learn all about lemon button fern care here.

Maidenhair

Maidenhair ferns come from the Adiantum genus, and the plants within this genus have different requirements.

For instance, western maidenhair (A. aleuticum) is native to western North America and grows in Zones 3 to 8. It’s a challenge to grow indoors because it prefers a cool, dormant season and warm days paired with cool nights.

Delta maidenhair (A. raddianum), on the other hand, is indigenous to warm climates in South America and is only cold hardy to Zone 10. Thanks to its tropical roots, it’s much easier to grow indoors.

It likes the warm temperatures of our indoor climates, though it needs humidity between 50 and 70 percent to thrive. Provide it with consistent moisture.

So, keep that in mind when hunting for your particular species.

Visit Nature Hills for a Delta maidenhair in a four- or six-inch container.

Rabbit’s Foot

Rabbit’s foot ferns (Davallia spp.) are named for the rhizomes they grow that are covered in a fur-like coating. When these rhizomes grow above the soil, they resemble those lucky rabbit’s feet that some people carry.

These plants live in tropical regions in Asia, Africa, Australia, and the Pacific Islands and need temperatures above 60°F, humidity over 60 percent, and bright, indirect light.

If you feel confident you can provide these conditions, hop on over to Walmart for a live plant in a six-inch pot.

Staghorn

I love all the eye-catching and unusual species in the Platycerium genus.

Staghorns and elkhorns are prehistoric marvels, and many of them make fantastic houseplants that grow without much input from you.

Bifurcatum is the most popular species and the easiest to grow. It’s also the one you’ll usually find in stores.

These plants need morning light or bright indirect light all day to grow best, but they will tolerate lower light. They like high humidity, around 70 percent, and are sensitive to wet roots.

I like to grow them mounted on wood because it’s nearly impossible to overwater them that way. If you’re a perpetual overwaterer like me, it’s the way to go.

You can find live S. bifurcatum plants in six-inch pots available at Home Depot.

Find tips on caring for staghorn ferns here.

Managing Pests and Disease

Indoors, there are only a few things to watch for on your ferns. Scale and spider mites are the most common pests you’re likely to run into.

These pests both suck the sap out of the plant’s leaves and stems. Both will cause symptoms like yellowing leaves, but spider mites will be accompanied by a fine webbing on the leaves and stems.

The fine webbing is a pretty good indication that your plant has spider mites, while the presence of little oval lumps, which are the scale insects themselves, tells you that scale is present.

If you identify spider mites, head to our guide to learn how to address them. If it’s scale you’re facing, visit this guide to help you combat this common pest.

When it comes to disease, root rot is the main cause for concern. Remember, these plants don’t like standing water on the roots. Root rot has two causes.

It can either be infection by pathogens in the Pythium genus or an abiotic condition caused by overwatering, essentially drowning the roots by depriving them of oxygen. Pythium pathogens need lots of moisture to survive, and infection can be promoted by overwatering.

If you see drooping, yellowing, or browning fronds, stick your finger in the soil. Does it feel any wetter than a well-wrung-out sponge? If so, you’re likely overwatering. Sometimes, the top of the soil will feel fine, but it will be soggier at the base, so it helps to feel down as deep as you can.

If you suspect root rot, pull the plant out of the container and wash away all of the soil around the roots. Prune off any soggy or black roots with a clean pair of scissors, then spray the roots with copper fungicide.

Wipe the container clean and make sure the drainage hole is open and clear. Repot the plant in fresh, clean soil and be extra careful not to overwater in the future. You are emptying that catchment container 30 minutes after watering, right?

Best Uses for Ferns

Ferns work both as specimens in a single pot or in groupings.

A specimen in the center of a container surrounded by trailing plants like pothos or philodendrons makes a noteworthy addition to the home.

You can also grow them in terrariums or, better yet, an antique Wardian case.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Herbaceous evergreen perennial/nonflowering vascular | Foliage Color: | Green, silver, blue, copper |

| Native to: | All continents | Maintenance | Low |

| Season: | Evergreen, or deciduous spring-fall | Tolerance: | Excess moisture, low light |

| Exposure: | Bright, indirect light | Soil Type: | Loamy, loose |

| Time to Maturity: | Up to 10 years | Soil pH: | 4.0-7.5 |

| Planting Depth: | Same depth as original container (transplants) | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Height: | Up to 6 feet | Uses: | Specimen, groupings, terrariums, dark areas |

| Spread: | Up to 4 feet | Division: | Polypodiophyta |

| Water Needs: | Moderate to high | Class: | Polypodiopsida |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Spider mites, scale; Root rot | Genera: | Adiantum, Asplenium, Athyrium, Cyrtomium, Davallia, Dryopteris, Matteuccia, Nephrolepis, Osmunda, Platycerium, Polystichum, Psychoides, Pteris |

Join in the Pteridomania

I can honestly see how pteridomania caught on. Once you have one, you suddenly want more.

Sometimes I look around my house and think to myself, “boy that corner could use a fern.” Given all the choices out there, there is a species for pretty much any spot indoors.

Which species is calling your name? What do you have growing in your home? Let us know in the comments section below! And if you have any questions that we didn’t cover, you can ask those in the comments, too.

Curious about other fern species beyond what we talked about? Check out these guides next: