Vaccinum vitis-idaea var. minus and var. vaccinum vitis-idaea

Most people outside of Scandinavia and Russia have their first experience with lingonberries in the form of jam or jelly, a far cry from growing their own.

I know lots of people who initially stumbled onto the stuff when they picked up a jar at that huge assemble-it-yourself furniture retailer that’s based in Sweden.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

That’s actually how I first tasted them.

I was in Sweden to interview an executive for said retailer and they stuffed us visiting journalists full of meatballs, toast skagen (skagenrora), and lingonberry jam for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

To be honest, I wasn’t that impressed. It tasted pretty much like any other berry jam to me.

Then we had dinner at a fancy Michelin-star restaurant on the coast of Copenhagen. They served pork with a lingonberry relish that was tart, a bit sweet, and spiced with goodies like allspice, juniper, and thyme.

And that’s when I got it. Lingonberries weren’t just some cranberry substitute that needs pounds of sugar to become edible. They’re complex, tangy, and perfectly balanced somewhere between sweet and sour.

While they’re often compared to cranberries, lingonberries have more natural sugar and a slight sweetness to balance the tart flavor.

When I learned that they grow well in some shade, I was totally sold. I, like a lot of people, have limited full sun exposure in my yard. When I find a food crop to stick into a shady spot, I’m all over it.

I’ve found these plants to be pretty much untroubled by pests and disease, adept at spreading around without becoming invasive, and extremely productive without needing much in the way of maintenance.

The only caveat is that you need to live in a cool region to grow them.

So, if the only experience you have with lingonberries is in jam, prepare to be immersed in their magical world. Here’s what we’re about to go over:

What You’ll Learn

Honestly, now my mouth is watering and I need to go make myself some toast with lingonberry jam, which is much better homemade than store bought, I might add.

Since my tummy is rumbling, we’d better get started!

What Is a Lingonberry?

Because they’re a bit challenging to grow and the berries aren’t as sweet as blueberries or raspberries, lingonberries just aren’t that popular outside of northern Europe.

There are two types grown for their fruits: the North American or wild lingonberry Vaccinum vitis-idaea var. minus (or subsp. minus) and the European or cultivated lingonberry V. vitis-idaea var. vitis-idaea.

In the wild, these plants grow in Scandinavia, Russia, Canada, the Pacific Northwest, and Alaska.

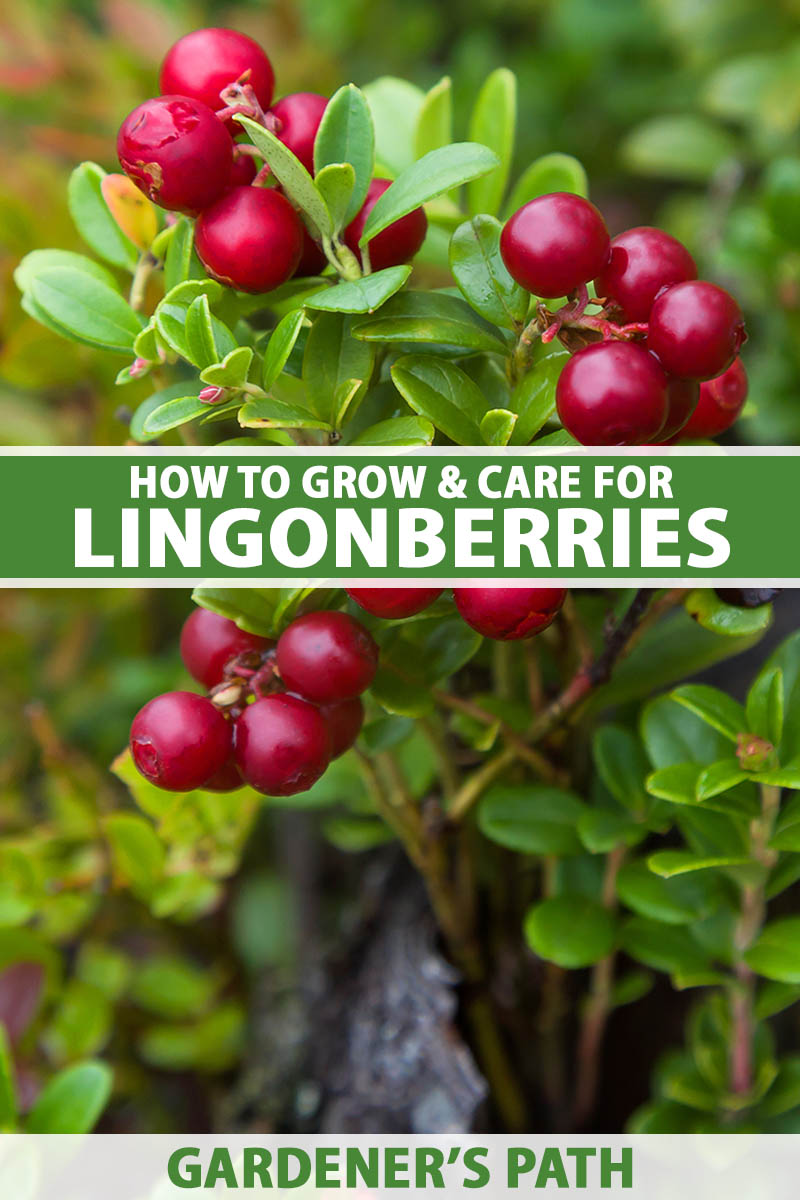

Both varieties are small evergreen ground covers closely related to heath and heather plants (Erica spp.) and both might go by the name cowberry, mountain cranberry, redberry, or partridgeberry.

Typically, wild plants are under about eight inches tall and spread two feet wide. Cultivated plants can grow twice as tall and wide.

The plants are covered in ovoid, leathery leaves with a darker green upper side and a lighter green lower surface. The leaves look extremely similar to kinnikinnick foliage except for a small notch at the top center.

The pink or white bell-shaped flowers appear in the spring and cultivated types might have a second flush in the late summer or early fall.

The flowers on the North American variety are about half the size of the European variety.

The berries that follow are small and red with a pronounced acidic bite. However, if you leave them on the plant after a freeze, they will soften and develop more sugar.

This is a cold-loving plant, as you can tell by its native habitat. It won’t survive in areas with sweltering hot summers, but -40°F won’t faze it – for the most part. If a hard freeze happens when the berries are young or the flowers are on the plant, it can kill them.

Cultivation and History

Lingonberries aren’t exactly a popular plant in cultivation, with under 100 acres in production worldwide as of 2006.

About a quarter of all commercially grown plants are in the Pacific Northwest, with some grown in Maine, Vermont, and Wisconsin. The rest are cultivated in Scandinavia and Russia.

Indigenous people in the parts of the world known today as the US and Canada where these plants are native relied on the dried berries as a winter food source. In Europe, they’ve been in cultivation since at least the Middle Ages.

Lingonberry Plant Propagation

Whether you buy a transplant or dig up a bit of a friend’s plant, lingonberries are easy to propagate at home. Most are propagated commercially through stem cuttings, so we’ll talk about that first.

From Stem Cuttings

If you’ve ever rooted a softwood cutting before, then you know how this works. It’s particularly easy with lingonberries.

In early spring, look for a four-inch piece of young growth. The wood should be flexible, not hard and rigid.

Cut it off at a 45-degree angle and remove any leaves from the bottom third.

Fill a four-inch container with water-retentive potting soil. Place the cutting in the medium a third of the way deep.

Water the soil well and place the container in an area with bright, indirect light indoors or dappled shade outdoors. Keep the soil moist and let Mother Nature work her magic.

By early fall, you should see new growth. If not, your cutting didn’t take and you’ll need to try again next year.

Take that healthy new plant and harden it off gradually by placing it in the area where you intend to grow it, for an hour on the first day. Then, put it back in its original protected area.

The next day, give it two hours in its new spot.

Add an hour each subsequent day until you’ve done this for seven days then transplant as described below.

From Rhizome Divisions

Lingonberries spread via underground rhizomes. Separating a runner from the parent plant is an easy, quick way to make new plants.

Just dig up your plant, leaving about a three-inch margin around the perimeter. The roots aren’t deep, so you want to dig out wide rather than going down too far. Six inches to a foot deep should do it.

Once you’ve unearthed your treasure, knock or wash away as much dirt as you can and examine the roots. You should see lots of areas where the roots connect to the above-ground stems.

Snip away a few sections of roots with a stem attached. Replant the parent plant and transplant the individual sections as described below.

From Transplants

In the spring after the last predicted frost date, dig holes 18 inches apart and three times as wide as the growing container.

Work an equal part of well-rotted compost into the soil that you removed.

Remove the plants from their containers and gently tease apart the roots.

Place each one in its hole so that it’s sitting at the same height as it was before, and fill in around with the amended soil. The roots should be positioned right below the soil.

How to Grow Lingonberry Bushes

While lingonberries can grow and fruit in partial sun, they will do best in full sun.

However, if you live somewhere that experiences hot summers, some protection from the afternoon heat is more important than full exposure.

Lingonberries need acidic soil. Anything below a pH of 5.8 is adequate, but ideally they need something around 4.5 to 5.5.

If your soil is too neutral or alkaline, you have a few options. One is to acidify your soil, and the other is to plant in a raised bed filled with acidic soil or amended soil.

The soil should be well-draining sandy loam, which is another reason that a raised bed might be ideal.

Yes, these plants are closely related to cranberries, but they don’t need boggy soil. The shallow roots should be kept consistently moist.

An inch of mulch made from straw, leaf or bark mulch, or compost will help those shallow roots stay moist.

A short period of drought or flooding won’t kill your plants, but do your best to avoid this because it will certainly stress them.

Drip irrigation is tailor-made for lingonberries, gently soaking the soil surface. You can use overhead irrigation, but it’s less ideal.

Don’t allow the soil to dry out at all. Not only will it cause drought stress, but it increases salt concentration in the soil, and lingonberries hate salt.

Some plants are happy to muscle out other cultivated plants or weeds to maintain their spot, but not lingonberries. They will meekly concede to anything that attempts to take over, so you need to do the work of keeping their area clear of weeds and nearby plants.

Feed with a low-nitrogen fertilizer in the spring and fall, but only if you haven’t seen new growth or you had a small crop. You should be getting about a pound and a half of berries from each plant.

Otherwise, skip the feeding unless a soil test indicates that your ground is deficient in something. Overfeeding can actually cause dieback and promotes root rot.

Don’t use a fertilizer that contains sodium or chloride because lingonberries are sensitive to both.

The plants can take up to seven years to mature, so don’t worry if you don’t have a full harvest until that time.

In order to produce large yields, you should grow a pollinating cultivar. You can get away without this, so long as you have two plants of the same variety, but a pollinating cultivar of a different type will improve production. We’ll talk about some good options shortly.

The flowers rely on pollinators like bees, butterflies, and flies. Wind doesn’t spread the pollen effectively.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full to partial sun in cool regions. Partial shade is tolerated in hot regions.

- Keep the soil consistently moist but not soggy.

- Only feed if plants appear to have reduced production or a soil test indicates you should.

Pruning and Maintenance

Don’t prune young plants at all. Let them grow for at least five years unchecked.

Lingonberries bloom on one-year-old wood at the tips of the branches, so any pruning should be done with the goal of increasing the total number of shoots.

Commercial growers mow half of their plants down each year, but at home, just snip half of the branches about halfway back each winter to encourage new shoots to form.

Don’t forget to keep weeds far away. Seriously, these plants can’t stand up to weeds.

Plants produce for over 20 years with proper care.

Lingonberry Cultivars to Select

It’s much easier to find lingonberry cultivars in places like Scandinavia and Belgium, but you can find them in North America if you keep an eye out.

For instance, Fast Growing Trees carries the European species.

Here are some of the best options if you’re interested in growing a specific cultivar.

All of these are bred from the European variety since the North American species hasn’t been extensively cultivated and marketed (yet?):

Ammerland

This cultivar has been around for a long, long time because it’s extremely vigorous and produces a lot of fruit. It will grow up to 14 inches tall with lots of large berries.

Entsegan

This vigorous grower produces at least a pound and a half of mild flavored berries on a 15-inch-tall plant.

Erntedank

‘Erntedank’ can be relied on to produce two crops per year on a 16-inch-tall plant. The berries are petite but flavorful.

Ida

‘Ida’ produces up to two pounds of large, dark red berries on a mere seven-inch-tall plant. It’s the most productive cultivar available to home growers.

Moscovia

Quick-growing ‘Moscovia’ (aka ‘Masovia’) will reach three feet in width and 15 inches tall in just a few years. It’s highly productive with mild berries.

Red Pearl

The fruits on ‘Red Pearl’ are mild and appear earlier in the year than most other cultivars. This cultivar is often used as a pollinator rather than for production because it’s low-yielding.

Root rot resistant, it grows to 15 inches tall.

Regal

‘Regal’ ripens early in the year with small, tangy fruits. However, it doesn’t produce a lot of them, which is why it’s often used as a pollinator or an ornamental.

Sanna

While ‘Sanna’ stays short, rarely breaching six inches tall, it produces a lot of fruits in the summer.

The fall crop is a bit smaller. It grows to about nine inches tall and the berries are medium in size.

Scarlet

‘Scarlet’ is a better option for those looking to keep a pollinator or an ornamental around.

It blooms profusely, but the berry production is middling. It grows to eight inches tall with medium-sized fruits.

Splendor

This plant is large, up to 18 inches tall, with medium-sized berries. It takes a few years to get going, but once it does, it produces a large yield.

The blossoms can tolerate light frost so you don’t risk losing your crop to a late freeze, and it’s resistant to root rot.

Susi

While this 10-inch plant will produce respectable summer and fall harvests,‘Susi’ (aka ‘Sussi’) doesn’t yield a lot of its medium-sized berries. Best used as a pollinator, it’s resistant to root rot.

Managing Pests and Disease

Nothing to see here. Move along.

Okay, obviously no species is going to be completely pest and disease free all of the time, but a properly situated and cared for lingonberry will rarely have issues.

Root rot is really the only major problem you might encounter.

Root rot can have two causes: the roots may be sitting in too much water for too long and they simply start to rot, or they may be infected by oomycetes in the Phytophthora genus.

Phytophthora needs an abundance of water to thrive, unsurprising since oomycetes are related to algae, and can be avoided if you take care not to overwater.

If rot is present, the aboveground parts of the plant will droop and wilt.

Since you can’t tell what’s causing the problem just by digging up the plants and looking at the soggy roots, you’ll need to treat them as though we’re assuming the pathogens are present.

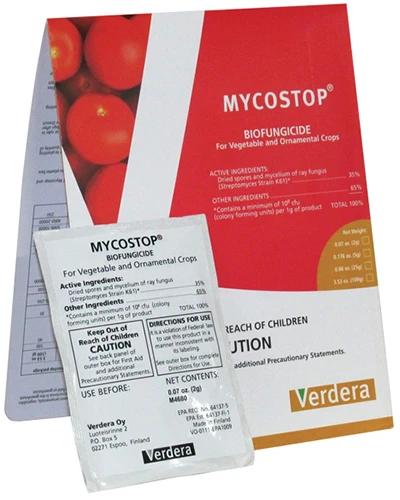

Pick up some Mycostop at Arbico Organics in a five- or 25-gram pack and mix it according to the manufacturer’s directions. Treat the plant every two or three weeks for at least eight weeks.

I swear by this stuff for treating root rot. It has saved several of my plants.

Harvesting Lingonberries

Depending on where you live, mature lingonberries may produce two crops each year. The first one will be ready in midsummer and the second in mid-fall, if the conditions are right.

The fall crop usually produces fewer, larger berries than the summer crop.

In northern latitudes with short growing seasons, you’ll probably only see a midsummer crop.

The fruits are ready to harvest when they are dark red and firm but not hard. If they aren’t completely red, allow the berries to ripen longer.

Use a blueberry rake to harvest or hand-pick.

Huckleberry Comb Berry Harvester

This gorgeous wood version from Garrett Wade is made in Germany and would be perfect for your lingonberry harvesting adventures.

You can leave the berries on the plant until after a frost and they’ll become sweeter, but you’ll want to protect the plant from herbivores if you opt to do this.

Preserving Lingonberries

Lingonberries are most often preserved rather than eaten fresh. They can be dried, turned into fruit leather, pickled, or of course, made into jams and jellies.

If you don’t have a go-to recipe already, visit our sister site Foodal for a simple jam or jelly recipe to start with. Try adding cloves, nutmeg, salt, cinnamon, and allspice to taste.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Though they’re small, weighing under 0.45 grams each, lingonberries are packed with antioxidants, anthocyanins, and flavonoids.

They’re used to create liqueurs and wine. While lingonberries of course work well cooked with some sugar to make all kinds of desserts, I’m a savory gal and you know I’ve figured out how to make a lingonberry relish like that one that made me into a convert.

If you want to give it a go, combine eight fresh bay leaves, 10 cloves, 12 juniper berries, five thyme sprigs, and a small sprig of rosemary. Tie everything up in a cheesecloth packet.

Now, grab a six-inch stalk of lovage with leaves attached and chop it finely.

Mix it with one diced apple and one diced peach, nectarine, or apricot. Add in two tablespoons of diced shallots. Saute in a bit of vegetable oil until soft.

Add lingonberries, the spice packet, and a cup of water. Simmer for 10 to 15 minutes until everything is soft but not mushy. Salt to taste.

Serve it on top of your choice of protein or even veggies. I tried it on fried tofu the other day and it was fantastic.

Okay, my stomach is growling again!

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Evergreen fruiting woody shrub | Flower/Foliage Color: | Purple, yellow/green |

| Native to: | Russia, Scandinavia, North America | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 3-9 | Tolerance: | Drought, deep freezes, flooding |

| Season: | Evergreen, summer and fall crop | Soil Type: | Rich loam |

| Exposure: | Full sun to part shade | Soil pH: | 4.5-5.5 |

| Time to Maturity: | Up to 7 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | Up to 2 feet | Attracts: | Pollinators |

| Planting Depth: | Same as growing container (transplants) | Companion Planting: | Blueberries, bunchberries, hydrangeas, rhododendrons |

| Height: | Up to 18 inches | Avoid Planting With: | Cacti, rosemary, sage, succulents |

| Spread: | Up to 4 feet | Family: | Ericaceae |

| Growth Rate: | Slow | Genus: | Vaccinium |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Species: | Vitis-idaea |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Root rot | Variety: | Minus, vitis-idaea |

Light Up Your Garden with Lingonberries

Lingonberries are such attractive plants that many people grow them solely as ornamentals. Isn’t it nice that you can also eat them? And they’re delicious!

So, share with us how you plan to use your plants. Are you going to make Grandma’s lingonberry jam recipe? Or do you have something else in mind? Let us know all about it in the comments.

Then, if you’d like to expand your gardening repertoire, there are some other types of berries that you might want to think about planting. Check out the following guides next: