Pinguicula spp.

Ever purchased a roll of flypaper and wished it came with a flower? No, just me?

For a botanical bug trap that flaunts both ornamental beauty and carnivorous savagery, behold the butterwort.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Members of the Pinguicula genus, butterworts attract insects to their greasy and sticky foliage, only for the poor bugs to end up trapped on the leaf surfaces and then digested.

Gruesome, yet quite awesome.

Aside from its bug-eating tendencies, a butterwort also looks pretty sweet, especially when it’s in bloom – with a single glorious flower on a long stalk protruding from its tightly-packed rosette of leaves.

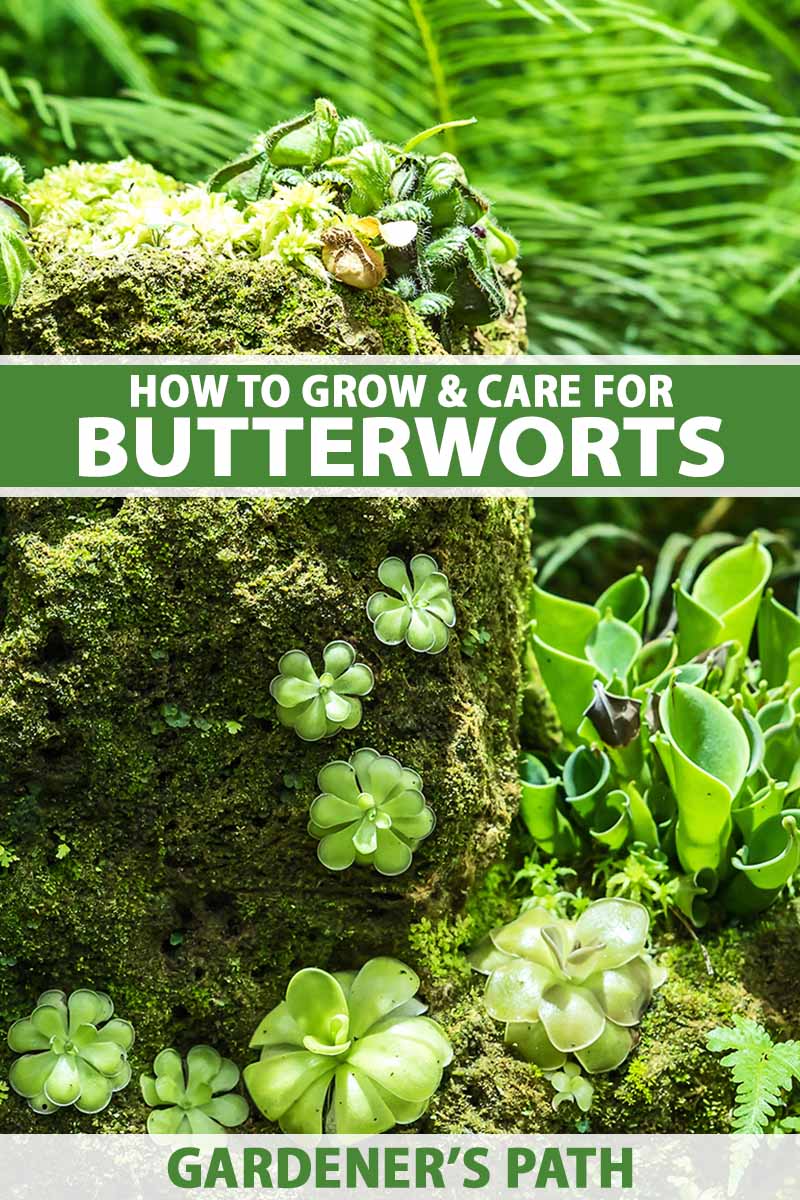

And for amplified aesthetics, you can grow a mass of Pinguicula plants in a single container, thanks to their small and shallow root systems!

Cultivating a carnivorous plant such as the butterwort indoors may seem intimidating at first, but folks often fear what they don’t understand.

After reading this guide, you’ll be oozing with understanding. Just like a butterwort secretes its trademark mucilage…

Here’s a taste of what’s to come:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Butterwort Plants?

As you probably could have guessed, butterworts belong to the bladderwort family, i.e. the Lentibulariaceae.

Comprising over 80 different species, Pinguicula plants – or “pings,” as they’re endearingly nicknamed – pack a ton of variety into a single genus.

Collectively, pings are native to every continent save for Australia and Antarctica, and are hardy in USDA Zones 1 to 11, depending on the species.

Across such a wide range of varied growing conditions, butterworts can be further categorized as temperate, warm temperate, or tropical.

Beyond bogs, you’ll also find species growing in the wild on calciferous cliffs and rocky slopes, along riverbanks, and some types even grow epiphytically on other plants.

Each requires slightly different cultivation practices when grown indoors… but more on that later.

Butterworts come in a variety of different sizes, colors, and morphological shapes.

They can be as small as an inch tall and one-and-a-half inches wide, or as large as 18 inches in height and 12 inches wide.

The leaves exhibit shades of white, pink, maroon, green, or yellow, while the flowers may be yellow, gold, purple, red, pink, or white.

You’re probably curious as to how butterworts catch insects in the first place.

The process begins with their leaves: each is coated in fine translucent hairs, which secrete a greasy, sticky mucilage. This mucilage smells of nectar and gleams with reflected sunlight, both of which attract hungry bugs.

As insects land on a butterwort’s leaves, expecting a smorgasbord, they become stuck instead, and smothered in the glue-like mucilage as they struggle to break free.

Some do – often losing a limb or two in the breakaway – but most remain trapped and suffocate.

As all this is happening, a secondary set of glands coats the caught bugs with digestive enzymes, which effectively melt their guts into a nice, readily digestible paste.

These glands then reabsorb the insect slurry, which allows butterworts to obtain nutrients that they’re unable to take up through the typically barren soils in their growing environment.

At this point, some species curl their leaves as a way to avoid enzyme runoff and protect their catch from the elements.

After digestion and absorption are complete, the bugs’ exoskeletons tend to remain in place on the foliage for the rest of the growing season, and are protected from bacterial rotting via a bactericide produced by the leaves.

Select species of butterworts will develop non-carnivorous leaves during dormancy that solely carry out photosynthesis, as a way to stay sated while enduring the absence of edible bugs in cold weather.

Come spring, new insectivorous foliage develops. This process saves the plant energy in the long run – producing and maintaining leaves that secrete digestive enzymes can be metabolically expensive.

Boy, that was a lot to digest!

Cultivation and History

At some point in their evolutionary history, the predecessors to butterworts found themselves in barren soils and in dire need of nutrients.

This nutritional demand spurred their carnivorous adaptation, which allowed them to obtain the nutrition they required from insects, rather than the soil.

Fast-forward to 1561, when Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner published “Horti Germaniae.” In this work, Gesner described butterworts as having “fat and tender-like” foliage.

Carl Linnaeus paid homage to this description by formally classifying the butterwort genus as Pinguicula, meaning “little greasy one” in Latin.

Let’s skip ahead a few hundred years to 1875, when Charles Darwin published “Insectivorous Plants.” This text contained the carnivorous plant findings that Darwin gleaned in the 16 years prior, which naturally included some tidbits on the butterwort.

Pings – and carnivorous plants in general – both fascinated and terrified laypeople, who had no idea that plants could munch on bugs. As a result, meat-eating flora became the subject of many scary tales.

Northern Europeans were aware of the antibacterial properties of these plants centuries ago, and rubbed butterwort leaves on cattle sores as a way to sterilize wounds.

Scandinavian folklore and historical accounts dating back at least 150 years describe inoculating milk with butterwort leaves to create a Lactococcus bacterial culture for fermenting a yogurt-like dairy product known as tettemelk, långfil, or filmjölk, among other names.

And enzymes produced by butterworts were also commonly used by Scandinavians to tenderize meat and curdle milk, until the early 1900s when other sources of protease enzymes became available.

By the 1960s, German botanist Siegfried Jost Casper had monographed all the known Pinguicula plants at the time.

In the 1970s, Donald Schnell and Jurg Steiger added new taxons to the collective body of butterwort knowledge.

At the hobbyist level, green thumbs far and wide enjoy growing butterworts in their homes and landscapes. Here, we’ll tackle indoor cultivation, starting with propagating new plants.

Propagation

You can propagate these bad boys in a variety of different ways. In order of decreasing difficulty, we’ll cover seeds, leaf pullings, offsets, and transplanting.

All of these methods work best when completed in late winter, rather than during the growing season.

Additionally, any water used in propagation should be distilled, gathered rainwater, or filtered via reverse osmosis, since these plants are pretty sensitive to the minerals and salts found in tap water.

From Seed

Some species such as P. lusitanica, P. villosa, P. chilensis, and P. antarctica will self-pollinate. But for others, you’ll have to hand-pollinate the flowers yourself in order to score some seeds.

When a butterwort’s flower is in full bloom, look down its “throat” – you’ll find the stigma hanging in front of the anthers.

Gently stick a toothpick past the stigma and try to collect pollen from the anthers. This may take several tries, but keep at it until you’ve harvested some.

Once you’ve got some pollen, dab it against the receptive side of the stamen, or the one facing the throat’s entrance. You can also cross-pollinate between different specimens of the same species.

If you pollinated successfully, the petals will fall off a few days later, and a seed pod will swell up, turn brown, and split in the weeks that follow.

After collecting the tiny seeds, you can keep them in the fridge – where they’ll stay viable for a few months – or sow them straight away for the best chance of germination.

When it’s sowing time, fill a seed-starting tray with a potting medium that the species in question prefers (more on that below), and sparsely sow the seeds onto the surface. Humidity should be provided by placing the tray in a sealed plastic baggie.

Place the tray in an area that’s bright and indirectly lit, with an ambient temperature above 64°F. Keep the media moist.

Give the seeds up to three months to germinate, maintaining the above-described conditions all the while. Once the seedlings produce a second leaf, you can remove the tray from the baggie.

Continue to provide care in the same way – sans-baggie – for an additional month. At this point each seedling should be potted up in its own container as described in the transplanting section below.

From here, treat the baby butterworts just like you would mature ones.

From Leaf Pullings

With these leaves, there’s no need for cutting with blades – you can pull them off by hand or via sterilized forceps!

You can remove up to half of the parent ping’s foliage without causing serious injury. Select mature, healthy, undamaged leaves for your pullings. Don’t yank, but pull gently.

In a seed-starting tray filled with the species’ preferred growing medium, lay the pullings right-side up on the media’s surface.

Provide similar lighting, moisture, temperature, and humidity as you would for seeds.

After several weeks in these conditions, buds and roots will start to emerge. Just like you would as described above, remove the humidity cover when a second set of leaves sprout.

After a few months pass, you can pot up each cutting into its own uncovered container and care for them as you would mature butterworts.

From Offsets

During dormancy, temperate butterworts sprout clumping, cone-shaped sprouts known as gemmae from their main growth point. These gemmae can be cut from their parent pings and propagated as new plants!

That little synopsis is pretty much the entire procedure, actually.

During dormancy, cut the gemmae from the parent plant with a sterilized blade, and place it pointed-side up in the species’ preferred growing medium.

Care for it in warm, indirectly-lit, and humid conditions until the gemmae root – you should have a mature butterwort by the end of the first growing season!

Via Transplanting

Keeping the species of your transplant in mind, fill a three- to four-inch shallow pot with its preferred growing media. Saturate the media with water 24 hours prior to transplanting.

Dig a hole large enough for the transplant’s root system, place the transplant in the hole, tamp the media down gently, then water it in.

Care for the transplant as you would a mature specimen, keeping the following tips in mind.

How to Grow

Temperate, warm temperate, and tropical butterworts share similar growing needs. But each also possesses unique requirements for cultivation.

General Requirements

All pings tend to prefer a moist substrate with decent drainage, humid conditions, temperatures of 60 to 85°F, and bright, indirect light.

Keep the potting medium moist by placing containers in a saucer of water, allowing for constant bottom-watering. Don’t let the saucer go dry!

Butterworts need a pH range of 6.0 to 8.0, which should be taken care of via the potting mix ingredients discussed below.

Despite insectivory being a notable butterwort trait, insect feeding should only be taken care of after everything else has been provided.

The substrate, humidity, light… all of this needs to be in place first, because digesting bugs takes a lot of energy and resources. An unhealthy Pinguicula that tries to digest insects can suffer leaf death or succumb to mold.

Taken care of everything else?

Then feed your butterworts a single insect per week, maximum, making sure the bug isn’t larger than a third of the leaf’s width. Acceptable prey includes mosquitos, gnats, flies, or even arachnids such as spiders.

Letting your pings catch their own prey or moving them outside during the growing season are even better ways for them to consume the exact amount of bugs that they need.

For outdoor feeding, make sure temperatures are warm enough – for the species that you’re trying to grow, that is – and that your plants are hardy enough to withstand the environmental light exposure.

Temperate Requirements

Temperate species such as P. vulgaris, P. macroceras, and P. grandiflora come from the northern regions of Asia, Europe, and North America, and are capable of surviving harsh winters.

For temperate species, provide a medium that’s two parts peat, one part perlite, and one part sand.

Temperate butterworts – especially the ones native to more northern climates – tend to go dormant in wintertime. During this time, they don’t typically require insect feeding.

Warm Temperate Requirements

P. pumila, P. lutea, and P. planifolia are a few examples of warm temperate butterworts, which tend to originate from the warmer parts of the Northern Hemisphere.

Grow warm temperate species in a 50/50 mix of peat moss and sand.

They won’t experience a full-on dormancy with gemmae sprouts like temperate varieties, but they will endure a “winter rest” period of sorts, with reduced growth and leaf size.

Your care for these species needn’t change during this time.

Tropical Requirements

Finally, we have the tropical butterworts, which come from equatorial regions and consist of species like P. gigantea, P. gypsicola, and P. moranensis.

Tropical butterworts need equal parts sand, perlite, vermiculite, and peat moss. Lava rock or pumice can be added for additional drainage.

When dry winters strike, these guys adapt by essentially turning into succulents – they drop their carnivorous leaves in exchange for smaller water-retaining ones.

During this time, insect feeding becomes unnecessary, and irrigation should shift from providing constant moisture to allowing the soil to dry out between waterings like you would with true succulents.

Growing Tips

- Provide butterworts with bright, indirect light indoors.

- During the growing season, place your plants outside in suitable conditions to let them feed as desired.

- If you choose to feed them indoors, or provide one bug per week, maximum.

Pruning and Maintenance

Due to their shallow and sparse root systems, repotting butterworts to avoid root bindage usually isn’t necessary.

Replacing the growing medium with new media every two to three years, however, is a solid strategy for keeping it disease-free and relatively fresh.

Any offsets that you don’t want to keep in place should be removed from the mother plant with a sterilized blade.

When blooms are spent, or if leaves appear damaged or sickly, remove with a sterilized blade as well.

Applying fertilizer to a ping isn’t necessary, especially with a regular diet of bugs, and many all-purpose plant fertilizers can actually harm these species.

Species to Select

As mentioned earlier, there are quite a few species of butterwort out there.

You may be able to track down specimens to add to your collection from specialty plant vendors and plant swaps, as well as from fellow carnivorous plant parents.

Here are a few species that combine mass appeal with distinctive characteristics.

Gigantea

Aka the giant butterwort, P. gigantea is the largest known Pinguicula, with a diameter of up to a foot!

Discovered and first described in 1987 in Mexico by Alfred Lau – a botanist who specialized in tropical butterworts, this plant flaunts yellow-green leaves compounded by its impressive size, and a light purple flower.

Plus, it produces mucilage on both the upper and lower sides of the leaves, which is unique among butterworts. That’s double an already impressive amount of bug-catching real estate!

Gypsicola

Another tropical butterwort from Mexico, this one looks weirdly awesome.

While many other butterworts have flattened and flat-lying foliage, P. gypsicola has skinny, tendril-like leaves that jut out about three inches from the center in all directions, making it look like the love child of a sea anemone and a sarlacc from the Great Pit of Carkoon.

Don’t let the strange foliage fool you – this species is quite capable of catching insects to eat. For logistical reasons, you may have to stick with providing tiny gnats, though.

Alongside the light green to pinkish-bronze leaves, this species produces slender flowers with pinkish-purple petals.

Moranensis

First described in Mexico around the turn of the 16th century, P. moranensis – or the Mexican butterwort – is arguably the most popular ping to grow as a houseplant.

The flower petals may be pink, purple, violet, and/or white, and the foliage varies in hue from bright yellow-green to maroon.

At about two to eight inches in diameter, it’s a pleasantly compact tropical butterwort that’s perfect for squeezing into tight spaces.

Managing Pests and Disease

Proper cultivation and health care go together like peanut butter and jelly. One cares for the plant itself, while the other protects it from external threats such as pests and pathogens.

Insects

“Hold up,” you may protest. “I thought these things ate insects?”

That they do. However, a few creepy-crawlies know to infest the parts of a butterwort that won’t trap and digest them, such as leaf undersides. Exhibit A?

Aphids

Soft-bodied sap-suckers, aphids consume plant phloem while excreting honeydew: a substance that inhibits photosynthesis and often leads to black sooty mold.

Applications of pyrethrin insecticides to the soil will help control aphids.

Slugs and Snails

These gastropods feed on leaf tissues with their file-like tongues, creating uneven smooth-edged holes in foliage. Plus, they’re freakin’ gross, if you ask me.

Thankfully, their grossness may serve as their undoing: by following their slime trails with a flashlight at night, you can trace these pests back to wherever they entered your home.

Entry points can be sealed up with expanding foam or barricaded with beer traps or copper strips.

Learn more about controlling slugs and snails in our guide.

Disease

Yes, butterworts are indeed “sick,” in a “righteous” or “totally tubular” kind of way. But it’s best that they stay figuratively so.

Even though working with plants can be a dirty endeavor, you should try to keep things sanitary by using sterilized tools and disease-free media.

Browning Heart Disease

Also known as center-to-edge rosette death, browning heart disease is caused by the simultaneous, tag-teamed attack of Fusarium fungi and nematodes.

Early warning signs include a loss of vigor, with stunted leaf growth and root development.

The signature symptom is a brown necrosis, which appears in the center of the rosette before spreading to the leaf tips. And the condition will kill a butterwort with swift and deadly precision.

Since these are soil-borne pathogens, it is extremely important to utilize sterile and disease-free soils. If your plants come down with this condition, then they should be disposed of right away.

Leaf Hole Formation

This condition takes place when the leaves touch down on soil that’s infested with either Botrytis or Trichoderma fungal microbes.

Upon contact with the infected soil, the foliage develops a hole at the contact site and expands to effectively melt the leaf away in a few days.

This won’t kill the entire plant, only individual leaves… but it’s still a problem, obviously.

Along with using disease-free media, make sure you aren’t fertilizing these plants (apart from feeding them bugs), since high nitrogen concentrations tend to encourage microbe proliferation.

Root Rot

When roots sit in oversaturated soils, they don’t tend to receive the oxygen they need.

As a result, the roots turn necrotic and die. In time, this will kill shoots above the soil line in a roughly equivalent amount.

Providing a well-draining medium for your butterworts is absolutely essential. Any root-rotted specimens – however tragic or minor their affliction – should be pitched.

Learn more about root rot prevention here.

Best Uses

The relatively small root systems of these plants make them ideal for jam-packing together in a single container. Not to mention, they work well as part of a terrarium planting.

Plus, the amount of species within the Pinguicula genus means any butterwort connoisseur looking to grow them all has a lifelong quest to look forward to.

Some are more rare than others, so be sure to call upon sustainable, cultivated sources for any new additions to your collection!

Some at-risk species to keep aware of are P. vulgaris – endangered in Maine and Wisconsin – and P. ionantha, which is threatened in Florida.

Just be sure to select containers of the proper size to account for mature dimensions, and note the temperate or tropical nature of your selected species to ensure a suitable growing environment.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Carnivorous herbaceous perennial | Flower/Foliage Color: | Yellow, gold, purple, red, pink, white/white, pink, maroon, green, yellow |

| Native to: | Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, South America | Maintenance: | High |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 1-11, depending on species | Tolerance: | Barren soils, humidity |

| Bloom Time: | Spring/summer | Soil Type: | Lean, moist |

| Exposure: | Bright indirect sun (indoors) full sun to partial shade (outdoors) | Soil pH: | 6.0-8.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | 5 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | Soil surface (seeds), depth of root system (transplants) | Attracts: | Bees, butterflies, flies, hummingbirds |

| Spacing | Touching to 12 inches, depending on species | Uses: | Houseplants, mass plantings, terrariums |

| Height: | 1-18 inches, depending on species | Order: | Lamiales |

| Spread: | 1.5-12 inches, depending on species | Family: | Lentibulariaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate to high | Genus: | Pinguicula |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, slugs, snails; browning heart disease, leaf hole formation, root rot | Species: | Gigantea, gypsicola, moranensis, and others |

Go Sport Some Butterwort!

If there’s an empty space in your home that just needs to be filled with some flora and you’re up for the challenge, you could do far worse than putting a ping there.

Carnivory aside, this plant certainly looks cool enough to warrant a spot in your houseplant lineup.

Have fun growing butterworts!

(… not that you needed my permission, or anything. I mean, just look at them!)

Have further questions? Other things to say? Head down to the comments section!

Hungry for more insect-eating plants? Try not to short-circuit your device by drooling over these carnivorous plant guides: