Have you ever dreamed of growing a pack of pitcher plants, a settlement of sundews, or a colony of Venus flytraps?

Well, don’t let your dreams just be dreams. Turn ’em into reality with a hearty dose of carnivorous plant knowledge, on the house.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

With this guide, you’ll learn the basics of caring for this unique type of flora, and gain the necessary know-how to put it into practice.

Here’s a preview of what’s ahead:

What You’ll Learn

Hopefully, you’ll have gained an even greater respect and appreciation for predatory plants by the time you reach the end of this guide. Let’s get into it!

What Are Carnivorous Plants?

A carnivorous plant is one that’s adapted to catch and digest animals via mechanisms such as snap traps, adhesive traps, and pitfalls that make up part of its anatomy.

Most of the time, the animals caught are invertebrates like insects, arachnids, and small crustaceans. But some large species consume vertebrates such as amphibians, lizards, rodents, and birds.

Despite their meaty diets, every carnivorous plant is photosynthetic and doesn’t actually consume animals for caloric energy. This carnivory actually evolved as a way of surviving in the harsh, nutrient-poor soils that these organisms call home.

The creatures they catch are high in nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur, which are used to supplement the little nutrition that the roots get from the soil.

Cultivation and History

The only trait that all carnivorous plants universally share is their meat-eating tendencies.

Botanical carnivory has independently evolved six or so times throughout evolutionary history across many different orders and families. There are more than 800 known botanically-carnivorous species out there… talk about diversity!

At multiple points in the past, some plants found themselves in tough environments and needed nutrients that weren’t available in the soil.

A few developed mutations that let them acquire these nutrients from animals. Organisms with these genetic anomalies thrived, reproduced, and presto: we’ve got flesh-eating flora today.

Typically, carnivorous plants are found in bogs, swamps, thinly-soiled areas of the tropics such as beaches, and nutritionally-void bodies of water. These habitats are worldwide, and oftentimes in unexpected places.

Take the Venus flytrap, for example: perhaps you’d think it might be found in exotic jungles or deep within rainforests, but it’s actually native to the wetlands of North and South Carolina!

Until the 19th century, most folks couldn’t fathom that anything leafy and green could consume animals.

This changed when Charles Darwin published “Insectivorous Plants,” a book covering 16 years of research. This enlightened many people, and carnivorous flora leached into horror stories as man-eating monsters.

This still has sway in modern day pop culture. From the 1986 film “Little Shop of Horrors” to the Piranha Plants that made their first appearance in “Super Mario Bros.,” flesh-eating clumps of greenery are still as scary as ever.

Today, carnivorous plants are grown in botanical gardens and greenhouses worldwide.

Hobby houseplant gardeners grow them for the challenge, and to witness the plant’s undeniable awesomeness. Plus, feeding them with that fly that’s been buzzing around your house all afternoon is a very satisfying form of revenge.

Propagation

Carnivorous plants can be started from seed, vegetatively propagated, divided, or transplanted.

Since this is a general growing guide, these recommendations are a bit cookie-cutter.

Specific research on the species that you’re growing will be required before you start. However, these tips will be a great starting point.

From Seed

You’ll want to prepare a 50-50 mixture of sphagnum peat moss and perlite in three-inch pots or a seed starting tray. Sprinkle the seeds on the surface of the medium, don’t bury them. Start your seeds under LED lighting… six to 10 inches under, to be specific.

Keep the pots or tray sitting in water, and keep the medium moist by lightly misting the surface with water that’s free of minerals and salts. Distilled or deionized water sources would be ideal.

Keep your pots covered with plastic, to prevent fungus gnat larvae from consuming the seeds.

The seeds can take anywhere from three weeks to nine months for germination to occur, so exercising patience is key.

Heads up, though: some seeds may require cold stratification in the refrigerator for four to eight weeks, depending on the species.

Vegetative Propagation

You can propagate most carnivorous plants via leaf cuttings, either in water or in a 50-50 mix of peat moss and perlite.

Take leaf cuttings from the outer edges of your adult carnivorous specimens, ideally when it is putting on new growth.

Submerge them in a container filled with sterilized water. The container you choose will depend on the shape of the leaf: you can’t go wrong with capped jars, but sealed test tubes can also work for skinny, tendril-looking leaves.

Keep the containers under a light source like you would with seeds. Change out the water if and when it starts to get cloudy, and remove any cuttings that become browned or moldy.

Move the cuttings into a suitable growing medium once they develop roots. This process may take up to a few months.

By Division

The best time to divide your plants is in spring, just as new growth is starting to emerge.

Work in a place that you can get dirty, such as a patio deck or a floor covered with tarp or newsprint. Take the dividee out of its container and gently tease it apart into the desired number of divisions.

By doing it this way instead of aggressively with a blade, you’ll get the healthiest divisions possible.

Remove any dead or dying leaves. Snip off the ends of the rhizomes on the outer edges of the division – if applicable – to stimulate new growth. You can even give the foliage a modest haircut to kickstart new foliar growth, too.

Place these newly divided specimens in their new pots, and presto, you’ve got divisions!

Transplanting

Prepare a pot with equal quantities of sphagnum peat moss and sand. Saturate the mix with sterilized water. Lightly pat it all down without compacting the medium.

Dig a hole in your prepped pot about the size of your transplant’s current pot. Gently tease out the transplant with your fingers or with gravity. Place it in the hole you made, fill it up, and water it all in.

How to Grow Carnivorous Plants

To grow a carnivorous plant indoors, it’s best to replicate the conditions of its natural habitat.

The environments that spurred carnivory in flora are fairly similar worldwide, so the following general tips should work for the majority of carnivorous species.

However, don’t be afraid to deviate from them in order to fit the needs of the specific species you’re trying to grow.

Some varieties may also respond well to growing outdoors in certain locales. We’ll cover that in more detail in separate guides.

Climate Needs

Most species require highly humid conditions, so your best bet is to use a terrarium. Cover the top with plexiglass to keep humidity high, and leave it ajar a bit as needed to provide necessary ventilation.

Standard containers such as pots work too, but you’ll have to keep the air around them very humid. Put them near kitchens and bathrooms, and/or set them on a bed of pebbles partially submerged in a water-filled tray.

Temperature needs are unique to each species, so you’ll want to check exactly what your specimen requires. A good starting point, however, would be to aim for temps of 70 to 75°F during the summer and wintertime temps of 55 to 60°F.

Exposure Needs

Direct light is the key to success with most species.

When grown indoors, this means placing specimens right next to south-facing windows in the Northern Hemisphere, or north-facing windows in the Southern Hemisphere. Make sure they soak up those rays for an hour or two, at least.

You can also use LED lights, if you’re lacking in the brightly-lit-windows department. A color range of 5000 to 5500k and a Lumen intensity of 5000 should work just fine.

Put the lights about six inches above the carnivorous species you’re trying to grow, with enough LED fixtures to cover them all.

Yescom offers an ultrathin LED panel on Amazon.

Soil Needs

Typical, nutrient-dense garden soil won’t fly with these bad boys, since they like their soils lean and with an acidic pH.

If you use the proper ingredients, then acidity takes care of itself. A mixture of two parts sphagnum peat moss to one part sand will do the trick.

An exception to this prescription would be for growing Nepenthes, or tropical pitcher plants. These guys need something a bit faster-draining, like an even mixture of sphagnum peat moss and a more coarse, porous ingredient like perlite or vermiculite.

Watering

Most species prefer wet soil in the warmer months and moist soil in the colder ones.

It’s important not to use tap or mineral-heavy water – these plants are so used to acidic, barren conditions that such water sources will stress them. Distilled water, snow melted to room temperature, or collected rainwater are your best choices.

Feeding

Taking your specimens outside in the summertime will allow them to feast as Mother Nature intended.

However, if this triggers “empty nest syndrome” for the clingy plant parents among us, then you can feed them indoors with an insect every week or two until their dormancy period begins. Don’t feed them more than this dosage…one bug a week, maximum.

Good food choices include flies and crickets, as well as non-insects such as slugs, spiders, and worms. Living food is ideal, so either break out the bug net in your yard or your wallet at the pet store.

Fertilizing

If feeding creepy-crawlies to a predatory plant turns your stomach, then there is a workaround.

A quarter-strength solution of organic fertilizer, applied once or twice a month during the growing season, is often an acceptable substitute.

However, this is less healthy than just giving these organisms what they’d consume in nature – it’s comparable to making your dog go vegan. If you feed your carnivorous houseplants insects, then supplemental fertilizer isn’t required.

Growing Tips

- Direct, bright lighting is pretty much standard for this class of flora.

- Be sure to keep the microclimate around your specimens highly humid.

- Use only distilled or naturally-occurring water sources when irrigating.

Pruning and Maintenance

Most carnivorous plants are herbaceous, so the only pruning you’ll have to do is to snip off dead, blackened leaves and other structures to encourage new growth.

Repotting (re-terrarium-ing?) should take place whenever your plantings fill or outgrow their containers. Given the overall trend of slow growth rates, this shouldn’t happen all that often.

Notable Specimens

There is a gargantuan amount of flora that consumes animals. However, some simply rise above the rest in attractiveness, popularity, and just how flat-out cool they are.

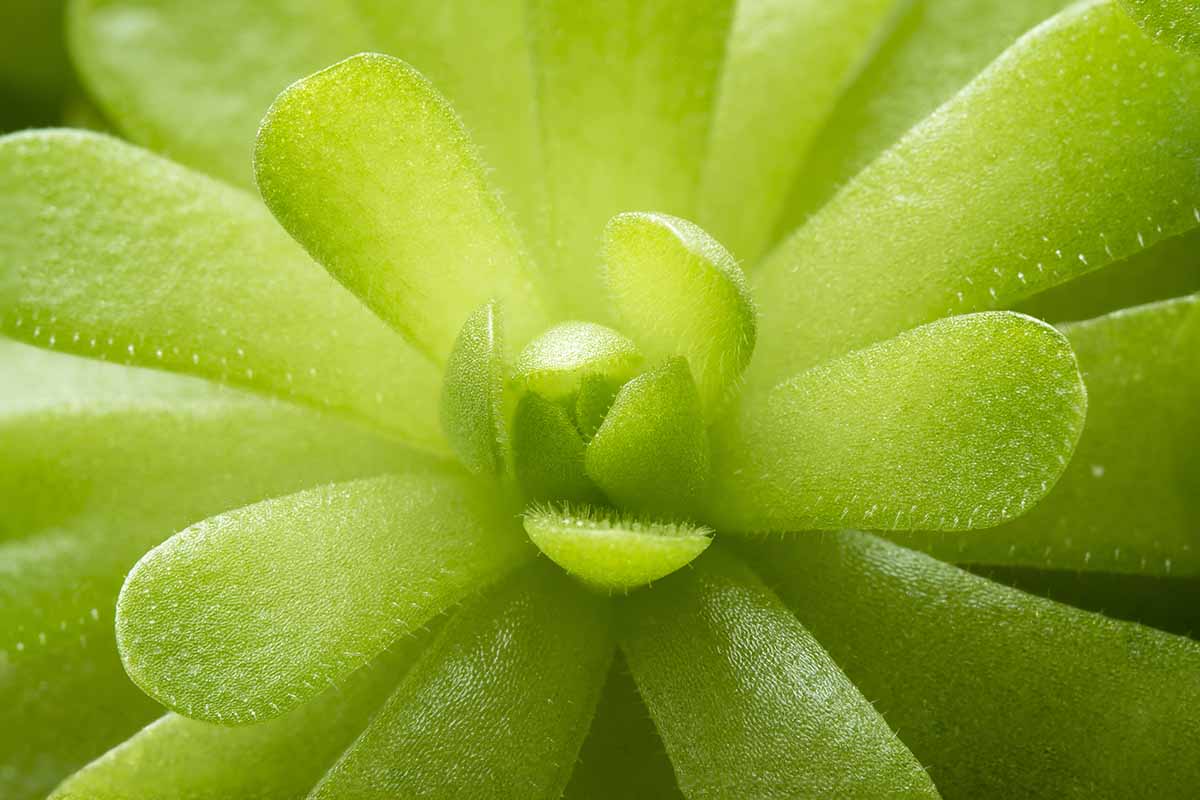

Butterwort

Named after its greasy, buttery leaves, butterwort (Pinguicula spp.) catches its prey in a sticky mucilage produced on the leaf surfaces.

Once the unfortunate insect lands, the leaves curl up in a cup shape, further trapping it. The insect is then digested externally.

With strikingly colorful flower petals, long stems, and lime-green deathtrap leaves, butterwort is a dangerous beauty.

Find tips on butterwort care here.

Pitcher Plant

Forming a pitfall trap in its pitcher-shaped leaves, the pitcher plant attracts its prey with a line of glands that secrete appetizing nectar.

This trail of deliciousness leads each insect down into the smooth throat of the pitcher, resulting in the bug slipping and falling into a digestive-enzyme-filled pool of death.

Contrary to popular belief, the lids do not snap shut upon catching prey.

But some species such as N. gracillis actually use the impact of falling rain to catapult insects from their slick lid undersides into their digestive pools, which technically counts as closing… at least for a moment.

Species commonly known as pitcher plants are those in the Nepenthes, Sarracenia, Heliamphora, and Darlingtonia genera.

These specimens vary in scale, ranging from thimble-sized to something resembling that of a milk gallon jug. Regardless of how big they are, they’re truly a sight to see.

If the pitcher plant has tickled your fancy, Nepenthes pitcher plants in six-inch baskets are available from JM Bamboo via Amazon.

Get more tips on pitcher plant care here.

Sundew

Sundews (Drosera spp.) have tall, upright leaves tipped with sticky-glanded “tentacles.”

They produce nectar to attract and adhesives to trap insects. Once it catches its prey, the tentacled leaf coils around the insect, effectively smothering it in a brutal finishing move.

The colorful glistening droplets produced by the tentacles give this species a deadly elegance.

Want a sundew for yourself?

Joel’s Carnivorous Plants sells a spoon leaf sundew in a three-inch pot, available from Amazon.

Read more about growing sundew plants here.

Venus Flytrap

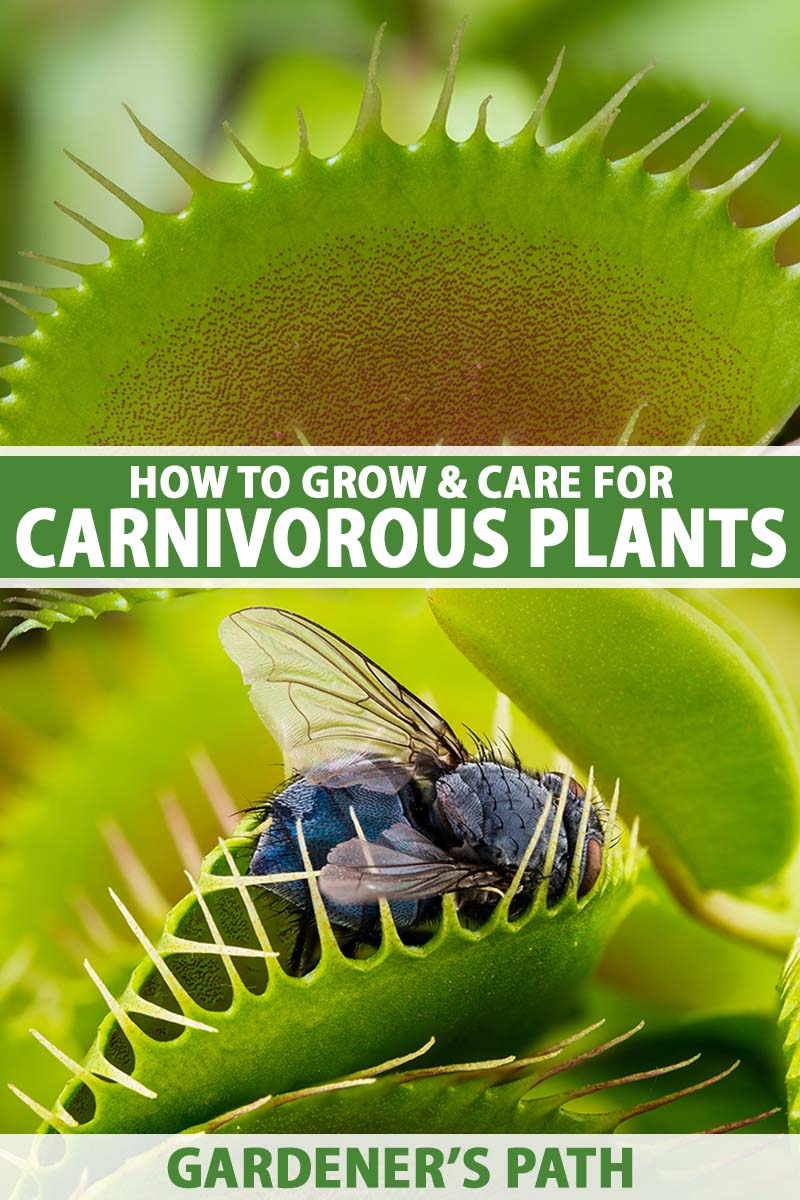

Arguably the poster child of the carnivorous plant world, the Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) traps flies with pairs of hinged leaves that bear spines along the margins.

When flies land on the open leaves and put pressure on one or more of the flytrap’s sensitive hairs, the leaves snap shut and begin to secrete digesting sap. After a 10-day digestion period, the trap opens and is ready to trap again.

If you wish to impress with the wildness of your garden, the Venus flytrap won’t let you down.

Predatory Plants has Venus flytrap specimens available in three-inch pots on Amazon, if you’re interested.

Find more tips on growing Venus flytraps here.

Managing Pests and Disease

Here are some of the issues you can run into while trying to keep your lil’ carnivorous pets healthy.

Fungus Gnat Larvae

Adult fungus gnats usually aren’t a problem for carnivorous flora. But their larval offspring are another story. These pests are an average length of less than five millimeters, with brown-stained translucent bodies and a black head capsule.

They are especially harmful for your carnivorous juveniles, and if they are present in the soil, they often consume seeds before germination.

They can even damage the root tissues, too, which leaves those roots vulnerable to pathogenic fungi in the soil. You don’t want these guys living in your carnivorous houseplants.

The product Gnatrol™ – which is essentially the spores of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis bacteria – can be used to drench the soil.

But since larvicides are very expensive and potentially harmful to carnivorous houseplants, you’re best off controlling the conditions which lead to the infestation of these creatures.

A five millimeter layer of medium to coarse horticultural sand on top of the soil should discourage egg-laying.

You can read more about fungus gnat control in our guide.

Mealybugs

Segmented and covered in a cottony wax, mealybugs love to hang out in the crevices where leaves and stems meet. They suck the sap out of flora and leave white, cottony puffs behind in their wake.

Their origins are oftentimes contaminated houseplants from vendors and friends – another reminder to always quarantine your new botanical purchases prior to integration with the rest of your houseplant collection.

Pesticides aren’t ideal for use against these pests, unless “twice-a-week applications forever” is a life sentence you’re okay with.

You’re better off applying 70 percent alcohol, mixed with a few drops of dish soap, via cotton swabs to the surface of your carnivorous houseplants every week, which desiccates mealybugs.

In addition, getting rid of plant detritus is essential as this can serve as mealybug breeding grounds. Mealybugs can also have a symbiotic relationship with ants that are attracted to the honeydew, so make sure to keep ants away, as well.

Learn more about how to deal with mealybugs in our guide.

Sarracenia Rhizome Rot

A common affliction for the trumpet pitchers of the Sarracenia genus, Sarracenia rhizome rot is caused by fungi in the Rhizoctonia and Fusarium genera. Infection results in rotten, mushy rhizomes that can eventually kill your plant.

It can occur as a result of frost damage prior to dormancy, when you over-fertilize, or irrigate your carnivorous houseplants with unsterilized water.

This burns roots, providing an entry point for pathogens. These pathogens end up in the phloem, which’ll lead to eventual wilting.

Prevention strategies include the initial quarantining of new specimens and the reactionary quarantining of infected ones, along with regular detritus cleanup.

Proper irrigation and not overfertilizing also go without saying. If infection does end up occurring, dispose of the afflicted specimen.

Best Uses for Carnivorous Plants

Carnivorous plants make for great companion plantings alongside many of the standard houseplants in your home.

While the latter exude peace and tranquility, the former give off a sense of intensity and savagery. Together, this results in a yin-yang effect that neither can pull off alone.

They are also very, very intriguing for botanical pros and newbies alike.

The specialized knowledge required to care for them poses a unique challenge for houseplant enthusiasts. Plus, having a Venus flytrap is a very utilitarian way to dispose of flies you were gonna swat anyway, so there’s that.

A Botanical Carnivore? You Couldn’t Ask for More!

It’s official: carnivorous plants are the coolest thing to happen to interior clumps of vegetation since the Monstera!

Feel free to cite or quote me on that.

The world of botanical carnivores is an exciting one, so have fun experimenting and exploring!

Have any experiences, questions, or comments of your own to share? Drop me a line in the comments section, and I’ll be sure to read and respond!

If learning about carnivorous plants provided some tasty food for thought and made you feel hungry for more, then make it four-course meal and read these articles next:

Hi there, I like your site! Great intro article, though I don’t think the lids of any Nepenthes close to trap the prey, do they?

You’re correct… my mistake. Good catch!