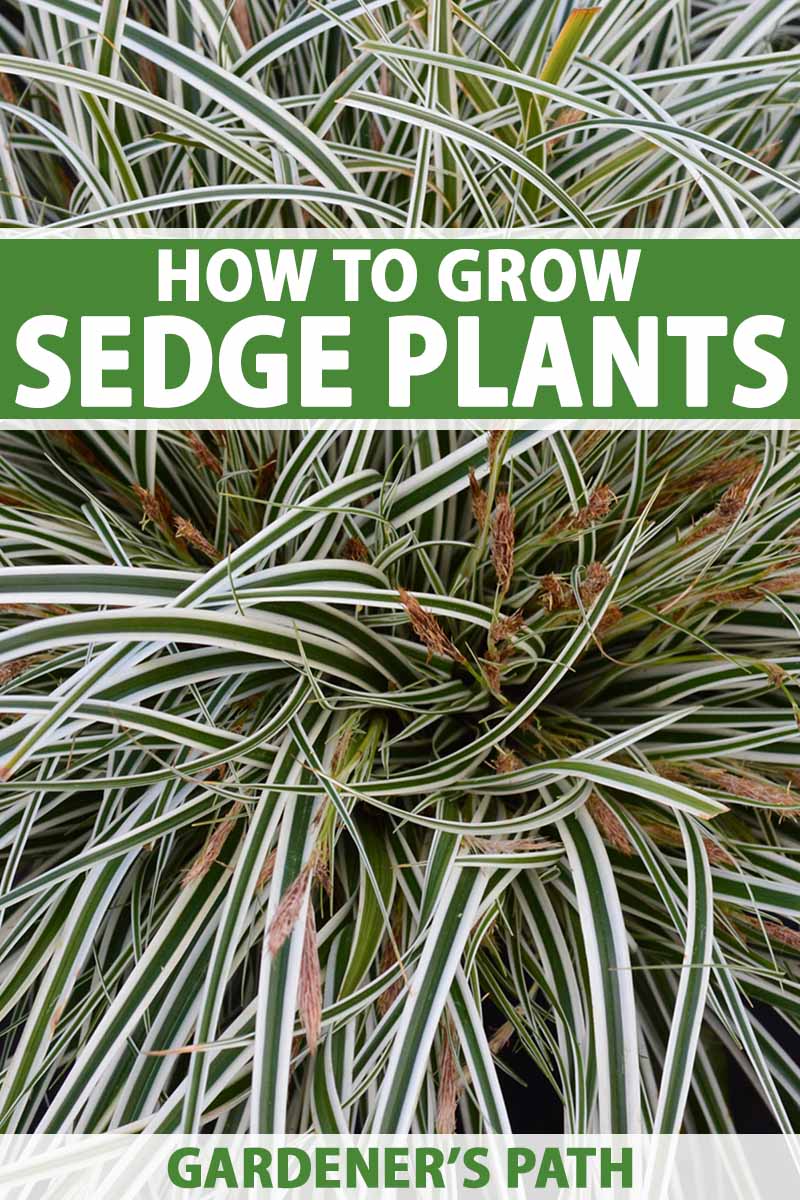

Cyperaceae Family

Is it a noxious weed? An elegant garden addition? A precious native plant? How about all of the above? Sedges are grass-like plants that are all this, and more.

Most people actually think of sedges as grasses, but they’re botanically different from one another. Maybe you’ve heard the adage “Sedges have edges, rushes are round, grasses have knees that bend to the ground?”

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

If so, then you know how similar the plants are and how tough they can be to tell apart, since we need a helpful saying to figure out which is which. But even that old familiar adage isn’t always enough to help you identify these grass-like plants with certainty.

Sedges, rushes, and grasses all belong to the clade Angiospermae.

Sedges are botanically classified in the Cyperaceae family, though when some people talk about these plants, they mean “true sedges,” which belong to the Carex genus. This is the largest genus in the family, by far, in terms of the number of species it contains.

In this guide, we’ll talk about all of the Cyperaceae family of plants, which includes at least 5,500 species, with a special focus on Carex species.

Almost all sedges need lots of moisture. They’re happier in boggy, wet soil than anything even remotely dry. Most prefer cooler climates. They also thrive in depleted or poor-quality soil.

That’s excellent news if you’re looking for something to fill a challenging spot in your garden. But it’s bad news if you have sedges taking over an area where you don’t want them to.

Don’t worry, we’ll cover the good, the bad, and the ugly, coming right up. Here’s what to expect:

What You’ll Learn

Sedges are an excellent solution to so many difficult growing challenges.

Soggy, shady, and poor soil areas can be difficult to fill, especially with something that won’t demand constant attention to keep alive. So without further ado, let’s dig into the wild world of sedges.

What Are Sedges?

Sedges, as we mentioned, are from the family Cyperaceae and are made up of a rhizome (though some have tubers) with fine roots, multiple leaf blades that emerge from one point, and a main stem that holds the flowering shoot or inflorescence.

Most sedge stems have three sides and are solid, with no joints or nodes. Looking at the stem is an easy way to tell sedges apart from grasses or rushes. The leaves themselves can vary dramatically, so don’t rely on those to tell you what you’re looking at.

Some species have needle-like leaves, others have broad, flat leaves, and some are toothed on the edges.

They can be any color from yellow to blue, and you’ll also see shades of red or orange. Growth habits vary, from tightly clustered groups of stems to sparse and distantly spaced growth along a single rhizome.

The leaves tend to cluster in threes and spiral up the solid stems, but it should come as no surprise by now that there are some plants that waver from this.

Many sedges are bisexual with both male and female parts contained in the flowering head, and they’re wind-pollinated. This means they tend to reproduce readily in the garden without companion plants to help things along.

Of course, with such a diverse group of plants, not everything is going to fit this description. Carex and Kobresia species, for instance, have unisex florets, but they are also wind-pollinated.

Speaking of reproduction, the seed head is made up of fruits called achenes that encase a single seed. The achene is covered in a sac-like membrane called a perigynium.

These plants can be annuals but most are perennials.

As we mentioned, a majority grow in areas with at least some periods of heavy moisture in the soil throughout the year, but there are others that grow in dry, rocky areas or in conditions somewhere in between the two.

You can find species that grow anywhere from USDA Hardiness Zone 2 to Zone 10.

Cultivation and History

These plants grow wild in every part of the world except Antarctica, and from sea-level river banks to high-altitude lakes or windswept steppes.

You can be fairly sure that wherever humans have disturbed the soil and made ditches or canals where water can gather, there will be some sedges making themselves right at home.

Of course, humans have also cultivated these plants as ornamentals and food. We know of sedges being cultivated in gardens as far back as about 300 BC and ancient Egyptians used the seeds and tubers as food, medicine, and to make papyrus for writing on.

When it comes to the home garden, almost all cultivated varieties come from the Carex genus, though species from some other genera are catching on.

Propagation

Some plants you practically have to beg to propagate and others are champing at the bit to go – sometimes too eagerly. Sedges fall in the second category.

From Seed

You can collect seeds in the late summer when the perigynia have matured and developed a dry, brown husk. Allow the seeds to dry on a screen or hanging by their stems in a cool, dry area with good air circulation for several weeks.

Alternatively, you can purchase seeds from nurseries or online.

For instance, Amazon carries one-ounce packets of pointed broom sedge (C. scoparia), which is a North American native with an interesting, fluffy seed head.

Once you have your seeds, plant them directly in the ground in the fall where they will receive the appropriate amount of light for the species.

If you purchase your seeds or store harvested seeds for planting in the spring, you’ll need to cold stratify them in moist sand at about 40°F for two months before planting.

Seeds germinate better in some light, so don’t cover them with more than an eighth of an inch of soil. Keep the soil moist. Most species will germinate in just a few weeks.

From Division

Thanks to their spreading growth habit, sedges are just about the easiest plants to divide that I’ve ever worked with.

To do the job, dig up a clump of leaves and roots on an overcast day in the spring. The size doesn’t matter, just choose the amount that you want to relocate. Once you have the plant out of the ground, you’ll divide up the roots.

So you can see these better, brush or wash away as much of the soil as you can. Then, pull apart clumps of roots with leaves attached. Some varieties have tough roots and you’ll need to use a knife to divide them.

Replant each clump in its new location and trim the leaves back by at least half. Water well.

From Seedlings

It’s easy enough to simply purchase a plant at the store and put it in the ground. Most of the time, you won’t need to do any involved prep. Your biggest job is to remove all weeds from the planting area.

If your soil is dramatically different from what the species prefers – heavy clay for a dry, rocky type plant, for instance – consider finding a different species rather than trying to make your soil fit.

There are so many options out there that there’s no point in trying to fit a square peg in a round hole.

Spacing depends entirely on the species you choose to grow, but most will need somewhere around a foot of space around them.

Dig a hole in the soil that is about the same size as the pot the plant came in. Remove the plant from its container and gently loosen the root ball.

Place in the hole with the crown at the same level as it was in the pot and firm the soil around it. Water well to settle the soil, and add more soil if necessary after settling.

How to Grow

Soil preferences depend entirely on the species that you’re growing. Some need something boggy and others prefer it dry.

Do a little research on types that prefer the sort of soil and sun exposure you have in the area where you intend to plant. Like we said, since there are so many options available, there’s no point in trying to force something to grow where it won’t be happy.

The pH can be anywhere between 5.5 and 7.5.

You can grow sedges in a container but you’ll need to be extremely selective about the type you choose. Those that need lots of moisture will probably struggle in a container, so look for those that do well in drier soil.

Many sedges can be grown as an alternative to grass lawns. Just note that they might go dormant in extreme heat and they tend to grow more slowly than grass – yay, less mowing!

There is no need to fertilize most sedges unless you are growing them as a lawn alternative. Then you’ll want to apply a nitrogen-heavy fertilizer once in early spring and again in early summer.

Down to Earth makes a lawn fertilizer called Bio-Turf that is perfectly balanced for sedges. Grab some at Arbico Organics in a six-pound box.

Lawn sedges should be mown when they reach six inches tall or so. Don’t cut them shorter than three inches.

Growing Tips

- Choose a species that prefers the soil and sun exposure that you currently have available.

- Soil pH should be between 5.5 and 7.5.

- Fertilize lawn-alternative sedges twice per year.

Maintenance

The leaves will turn brown and die back in the fall. Some varieties will still have a green center, while others die back entirely.

You can prune back the plant in the spring or fall, depending on your preference. Some people like to leave the brown leaves in place during the winter for some visual interest.

When you decide to prune, grab a handful of leaves and use pruners or heavy-duty scissors to cut the sedge back just above any green growth at the crown, or back to about six inches above the ground.

New leaves will emerge in the spring to replace the dead and cut-back stuff.

Our guide to pruning ornamental grasses can provide some additional insight.

Depending on which type you plant, you might ultimately spend more time doing routine maintenance to limit your plant’s growth rather than encouraging it.

Many wild and escaped species are a plague in cultivated spaces, and these plants spread via self-sown seed and underground rhizomes.

To keep yours from becoming a problem, hand pull any unwanted growth when they expand and spread beyond where you want them.

You’ll have to be diligent about this, which means you should plan on heading outside for a good pulling session at least once a month.

Not all sedges spread this aggressively, but keeping them in pots or raised beds is a good idea if you find that you can’t keep up. Landscaping cloth, mulch, and most herbicides are no help in trying to eliminate these tough little growers.

Species to Select

There are thousands upon thousands of different species and cultivars out there, and making a selection can be overwhelming.

Plus, sedges, grasses, and rushes are not only visually similar, but they’ve been named confusingly, as well. Some sedges even have “grass” or “rush” in their name.

It never hurts to pop over to your local nursery to see what they recommend, as well. They know your local climate best.

There are also a few classics that show up in gardens over and over because they’re so reliable and good-looking. Here are a few of the best species for home gardens:

Bulrush

I know, “rush” is in the name, but Scirpoides holoschoenus, or the roundhead bulrush, is actually a sedge. This plant is also known as club-rush and you may come across the botanical synonym Holoschoenus vulgaris.

Species in the Schoenoplectus genus are also commonly known as bulrushes.

The bulrush category is where you’ll find those plants with the big, brown cattails. And remember that old adage about sedges having edges? The ones known as bulrushes violate the norm. They have round stems.

Bulrushes from the Typha genus, on the other hand, are not sedges.

Club-Rush

You might see these also labeled as bulrushes (I know, it’s confusing), and there are some beautiful options within the Scirpus genus.

Woolgrass (S. cyperinus) has big, fluffy seed heads packed with brown seeds.

White rush (S. albescens) has pale green and white, needle-like leaves and is ideal for ponds.

Zebra rush (S. tabernae-montani ’Zebrinus’) has attractive green and white stripes alternating horizontally on each needle-like stem.

Cotton

Cotton sedges belong to the Eriophorum genus.

Another misnomer, cottongrass (E. angustifolium) is actually a sedge. It has fluffy, cotton-like seed heads and thrives in wetlands.

Deergrass

Also known as bulrushes (seriously, this is a confusingly named group of plants!), deergrasses belong to the Trichophorum genus. Many of these are native to North America.

Tufted bulrush (T. cespitosum) and Clinton’s bulrush (T. clintonii) are often sold at nurseries, especially those that specialize in native plants.

Hook Sedge

Hook sedges (Uncinia rubra) have little hooked ends on the seeds, hence the name.

Most cultivated types are red, such as ‘Belinda’s Find,’ which has bronze-red foliage that turns orange-red in the fall.

Grab a two-pack of #1 containers at Nature Hills Nursery to bring some color into your garden.

Nutrush

Neither nuts nor rushes, nutrushes belong to the genus Scleria. Some are considered valuable additions to the garden and wilderness areas, and others are considered invasive weeds.

S. microcarpa, for instance, is a problem in Florida. But whip-grass (S.triglomerata), which is not a grass, is endangered and restoration efforts are underway in some areas.

Look for plants in this genus at nurseries that specialize in native plant options.

Nutsedge

Also known as nutgrass (Cyperus rotundus), this species is native to parts of Europe, Africa, and Asia. It has spread as an invasive weed in North and South America.

How you choose to handle it depends on where you live. In areas where it may become invasive, grow it in a container or consider a different species.

These plants love wet areas like the edges of rivers, wetlands, and even places with underground piling leaks around foundations. They’re named for the tubers that they produce, which resemble nuts.

Papyrus

While you won’t usually find it anywhere but in specialty stationery stores, Egyptian tourist shops, and museum collections, papyrus (Cyperus papyrus) is exceptionally important.

It was one of our first portable writing surfaces and it is made from a sedge.

Even if you aren’t planning to craft a handmade scroll to record your history, the plants are stunning.

They have umbrella-like spindles at the end of long spikes that are sure to be a conversation piece.

Buy a plant to grow at home from Fast Growing Trees.

Spikerush

Spikerush (Eleocharis palustris) isn’t a rush, as you probably guessed. It grows wild in every state except Georgia and Florida.

It prefers wetlands and other super moist areas. And in the late summer, it produces nut-like fruits that wild wetland birds are “nuts” for (sorry).

Sawgrass

There are many types of sawgrass (Cladium spp.) that grow natively all across North America and throughout most temperate parts of the planet. They have serrated, saw-like leaves and most do well in incredibly wet, depleted soil.

They can be useful in restoring wetland areas. Some are being cultivated as a corn replacement for use in cellulose manufacturing and as a biofuel.

Water Chestnut

Ready to have your mind blown? Water chestnuts (Eleocharis dulcis) are botanically classified as sedges.

This water-loving Asian native is valued for its delicious tubers. It’s difficult to grow in the home garden unless you have a pond or boggy area.

White-Star Sedge

Also known as starrush whitetop, beaksedge, whitetop sedge, or white-star sedge, Rhynchospora colorata is a water-loving evergreen from North and South America.

It produces beautiful white flower-like growths that make this species a striking addition to the garden.

Want More Options?

To help you narrow things down a little, check out our supplemental guide, “15 of the Best True Sedge Plant Varieties for the Home Garden.”

Managing Pests and Disease

One of the marvelous things about these plants is that they’re so incredibly tough. Hardly any pests or diseases attack them, and those that do don’t usually cause much damage.

Herbivores

I’m going to start with a caveat: Sedges are an important source of food and shelter for rabbits, nutria, muskrats, mice, waterfowl, and birds. They’re also a vital part of the environment for lizards, snakes, frogs, and countless invertebrates.

That’s either excellent or terrible news, depending on your goals.

If you want to add vital resources for wildlife to part of your property, they will be most welcome.

However, if you want to enjoy the display of your plants in a carefully-tended patch of your garden, you’re probably going to have to make an effort to protect them.

Rabbits, in particular, will likely think you’ve given them a lovely buffet. On the other hand, deer don’t seem as interested, so there’s that.

Read our guide to learn about how to deal with rabbits in the garden.

Insects

If you do a quick internet search for sedge pests, you’re more likely to find results talking about sedge as a “pest” rather than the insects that attack it.

That’s because very few insects bother it, and those that do feed on it don’t typically do any serious damage, whereas many of these species of plants have a tendency to become invasive. Aphids are likely to be the only type of insect pest you’ll encounter.

Aphids

A variety of aphids, but primarily the bronze or black bulrush aphids (Schizaphis scirpi), feed on water-loving plants in this family. They live at the base of plants and usually don’t do much, if any, damage. You might see a yellowing leaf here or there.

You don’t need to do anything to deal with an infestation unless you really want to, especially since bulrush aphids won’t bother other families of plants.

If you decide they’re driving you crazy, read our guide to learn how to manage an aphid infestation.

Disease

If your sedge comes down with some sort of disease, call me, because I’m pretty convinced that diseases among this family of plants are a myth.

I’ve seen pictures of rust fungus on a few plants, but with how talented people are with Photoshop these days, I’m still not sure…

Alright, I kid. But seriously – these plants are pretty tough.

Rust

All sedges are susceptible to rust to some degree, but some species and cultivars are more prone to contracting or succumbing to it. You can always do a little research before purchasing a particular plant to see if it’s resistant or not.

Rust is caused by several different species of fungi in the Puccinia and Uromyces genera.

Regardless of which species pays your plants a visit, you’ll see dark little rows or spots of fungi on the leaves. It spreads when there is lots of water around, whether that’s in the form of humidity, rain, or water splashing from the ground.

You know, the kind of conditions that this particular type of plant loves.

If your plants are impacted, you can trim away the infected bits and treat what remains with copper fungicide. To avoid infection, look for resistant cultivars and water at the soil level rather than on the foliage.

Best Uses

Sedges can be used as both specimen plants and lawn alternatives. They’re ideal for rain gardens because the roots help to hold the soil and slow runoff. They can also draw moisture down into the soil.

Just be cautious and do your research to avoid planting a variety that is considered invasive in your area, to avoid problems down the road. Your local extension office can help you figure out which species to avoid.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Grass-like flowering annual or perennial | Foliage Color: | Yellow, green, blue, silver, orange, red, bronze, brown |

| Native to: | Every continent except Antarctica | Tolerance: | Drought, freezes, wet roots |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 2-10 | Maintenance | Low |

| Bloom Time: | Spring, summer, fall | Soil Type: | Clay, loamy, sandy |

| Exposure: | Full shade to full sun | Soil pH: | 5.5-7.5 |

| Time to Maturity: | About 2 years, depending on species | Soil Drainage: | Poor to well-draining |

| Spacing: | 6-18 inches, depending on variety | Companion Planting: | Astilbe, hosta, iris, oak, rudbeckia, senna, milkweed, fern |

| Planting Depth: | 1/8 inch (seeds), crown at soil level (transplants) | Uses: | Specimen, mass planting, container planting, border, water garden, drainage garden |

| Height: | 4-60 inches, depending on species | Order: | Poales |

| Spread: | Indefinite | Family: | Cyperaceae |

| Water Needs: | High to low, depending on species | Genera: | Carex, Cyperus, Eriophorum, Rhynchospora, Scirpoides, Scirpus, Scleria, Trichophorum, Uncinia |

Sedges Have the Edge in Difficult-to-Cultivate Spaces

There are so many sedges, from the marvelous ornamentals we use in our gardens to the invasive pests that have escaped from their native home.

So long as you are thoughtful about which one you choose, you can have an exceptionally carefree plant to help beautify your space.

I can’t wait to hear what species you decide to go with. Let us know in the comments! And tell us if we missed one of your absolute favorites.

If you want to learn a bit more about grass-like plants and using them in the garden, we have a few guides that I hope you’ll find interesting:

I have a sedge in my yard and I’ve looked at pictures but I’ve not been able to identify It. I live in Indiana and I am wanting to have native plants in my yard. I’ve looked at pictures of yellow nutsedge but I’m thinking this isn’t it.

Hi Gloria, I’ve managed to retrieve your picture, it uploaded but didn’t attach to your comment. Sorry for that!

Hi Gloria, it definitely looks like a sedge, but there are dozens of native species in your area and dozens of non-natives that have naturalized. It could be an escaped C. morrowii (most likely) or a C. albicans. If you want to narrow it down, it would help to have images of the seedheads.