A healthy, well-trained climbing rose in full bloom is one of the most magnificent things to behold in the garden.

Not only can these plants hide a myriad of ugly things (wire fencing, a run-down wall, the ugly side of a house…), they transform the area into a fairy-tale filled with color and fragrance.

It’s my theory that the potential for that ridiculously glorious display is part of what intimidates many gardeners.

They look like a lot of challenging work has to be involved, but that’s not really the case. If you can tie a knot, you can train one of these plants.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

So why do you sometimes see unruly, inelegant climbing roses? Neglect may be the cause, or a simple lack of knowledge on the part of the gardener.

Not knowing the appropriate way to train them in the first place is a common problem. We’re going to make sure you don’t fall into this category.

To make that happen, here’s everything we’ll go over in this guide:

What You’ll Learn

By the way, if you don’t want to deal with the pain of being stabbed repeatedly while trying to train your rose, there are lots of thornless cultivars available.

Many of the thornless types are not just beautiful, but are considered some of the prettiest options out there!

What Are Climbing Roses?

Technically, roses aren’t really climbing plants. True climbers send out tendrils or suckers to help them work their way up trees, rocks, and manmade structures.

Roses just have really long stems, and if you want them to “climb” a structure, you’ll have to give them some help.

Growers generally classify these types of long-caned roses as ramblers or climbers. Climbers tend to be less vigorous and are less likely to take over your garden than ramblers.

They also usually have larger flowers that grow singly rather than in groups. Most climbers are repeat-flowering and have stiffer canes.

Ramblers, on the other hand, are usually quite vigorous and can overwhelm a small space. They also usually have smaller flowers and these often grow in groups rather than singly.

Most flower once and are done for the season. Think of ramblers as closer relatives to wild roses, while climbers are the refined cousins.

You can learn more about caring for climbing roses in our guide.

Cultivars to Select

There are many excellent cultivars out there that you can find at local nurseries or online. It never hurts to reach out to your local rose society as well, because they can point you in the right direction in terms of what will work well in your climate.

The following are good choices for just about any region:

Don Juan

As alluring as its namesake, this hybrid tea climber has bright red, full blossoms with a classic rose fragrance. It’s hardy, disease-resistant, and a vigorous grower with a repeat display that lasts all summer.

Pick up one in a three-gallon container at Fast Growing Trees.

Joseph’s Coat

‘Joseph’s Coat’ never fails to draw comments. Truly a blossom cloaked in many colors, this floribunda has large, fruity-smelling flowers with pink, yellow, and salmon petals. The flowers appear repeatedly in clusters throughout the growing season.

While this cultivar is moderately susceptible to fungal diseases, it’s vigorous and hardy enough to withstand even the freezing winters in Zone 4.

Grab a live plant in a gallon container at Amazon.

Strawberry Hill

One of my favorites in my own garden, I have this David Austin rose growing in a large container against a wall and it garners compliments from everyone who sees it.

It stays fairly petite at under 10 feet tall, and is covered head to toe in classic pink fully double flowers that smell like myrrh and honey. From spring until fall, new blooms pop up constantly for a reliable display.

Westerland

For something more disease resistant, look to the bright apricot flowers of ‘Westerland.’ From famed breeder Reimer Kordes, the huge five-inch double blooms are produced in large clusters and flower repeatedly throughout the entire summer.

‘Westerland’ has a pleasing, spicy fragrance and is extremely vigorous. Protect this one from late spring frosts and you’ll be treated to an ongoing, vibrant display.

Nature Hills Nursery has this excellent option in #2 containers.

Zephrine Drouhin

‘Zephrine Drouhin’ is a classic. This thornless Bourbon rose has been around since 1868, and when gardeners mention their favorites, this one consistently tops the list. When it is healthy and happy, this cultivar is incomparable.

With diligent deadheading, it’s positively smothered all summer in massive, deep pink, full flowers with a heady damask fragrance. A little bit of shade won’t impact the display one bit, either.

The drawback is that it’s susceptible to black spot and powdery mildew. But don’t let that put you off. This one is definitely worth having around.

If you agree, pick up a #3 container at Nature Hills Nursery.

When to Start Training

In the first year, your rose will be adjusting to its new home and you don’t want to stress it out further by bending and twisting the stems. Just let it grow and do its thing for the first year until it becomes established.

In the second or third year, so long as the canes are lengthy enough, you can start training in the spring. You can’t train older, woody canes. Look for the young, pliable ones and do your work before they start to harden up.

The Basics

It probably goes without saying, but you want your canes to grow up rather than out. Some climbing roses have fairly strong canes that don’t get too long, and you can allow these to grow into a shrub shape with arching branches.

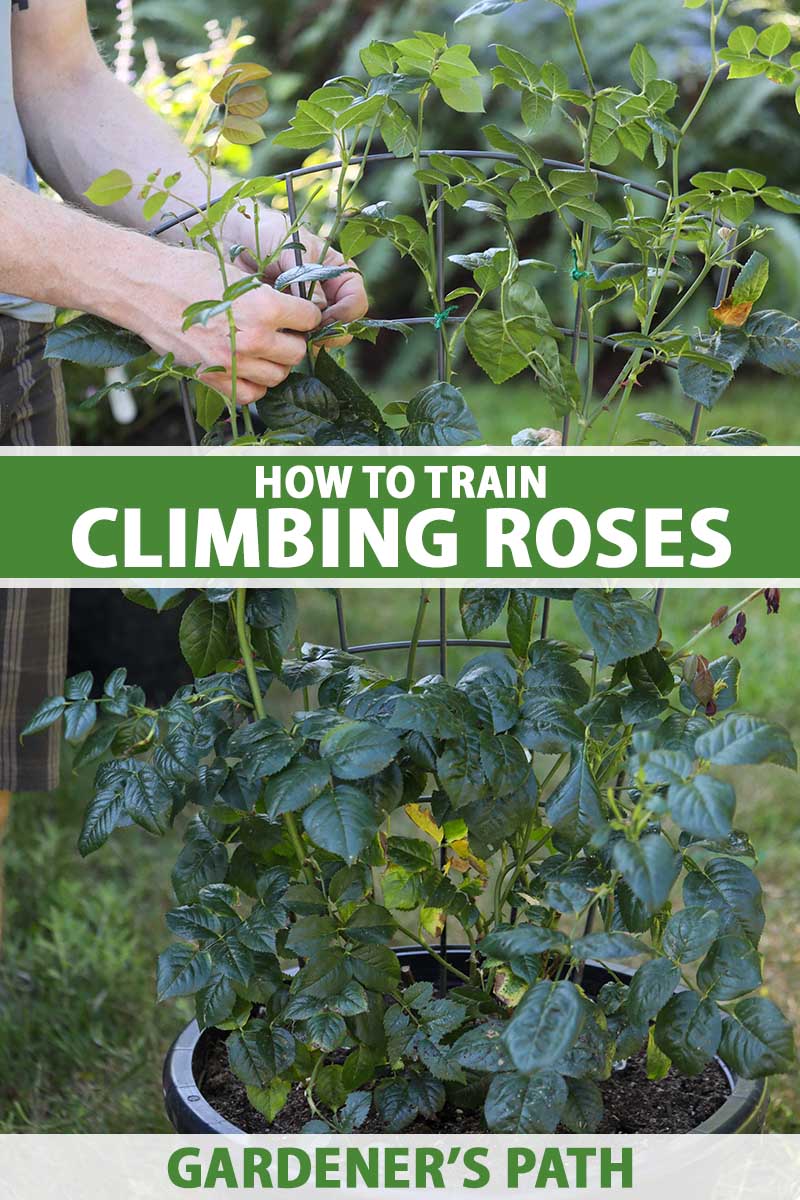

In order to encourage your plant to climb, you need to give it something to attach to. To achieve this, you’re going to fasten the canes to your chosen structure.

People train roses to grow up all kinds of things, from arbors and trellises to fences and pillars. Anything strong that you can attach wire or twine to will do.

You’re going to work with young, green canes rather than any woody, older canes, as mentioned above. Each year, you will fasten new growth into the shape you want it to have on your chosen structure.

If you stop training, the ends will fall out and away from the structure. They won’t continue climbing on their own. It’s important to maintain your climbing plants each spring.

Establish Your Support

When you put your plant in the ground, put the support in place at the same time.

It’s possible to add a trellis or obelisk after the plant is in place, but you run the risk of damaging the roots or canes, not to mention yourself when the prickles grab onto you.

Of course, if you’re using a permanent structure for support, you’ll put the plant in the ground nearby.

What kind of support works best? You’ll need something strong. With few exceptions, roses can become heavy and large, and they can tip over a thin wire arch or trellis – trust me, I’m speaking from experience here.

Use wood or metal that is anchored into the ground. Anchoring is important. If you grow a rose up an arbor that has not been anchored, for example, a strong wind can blow the whole thing over.

Say you’ve spent the past 10 years training and caring for a rose and it has become a majestic centerpiece. One strong gust and all that hard work goes down the drain without proper anchoring.

If you’re growing up a wall, you’ll need to put a trellis or training wires in place first. Again, a rose doesn’t have suckers so it can’t attach itself to a smooth surface.

If you’re growing up a column or pole, you can simply tie the canes in place around it – no need for a trellis or wires here.

Prune

Before you start training the canes, prune away any dead, misshapen, or diseased ones.

Next, take out any short or thin canes, even if they’re healthy. In the end, you want to keep about five to seven of the longest canes to work with. Each one should be at least as thick as a pencil.

Each year to follow, you’ll need to go in and repeat this process. But leave any healthy, trained canes in place.

You can train a few new canes each year to fill in or expand your display, but you don’t want to let the shrub become overcrowded. A lack of proper airflow can lead to fungal disease.

If your plant has any offshoots that are heading totally in the wrong direction, just snip them off at the base.

It can be really hard to train a cane to grow against a wall if it’s naturally growing away from it, so it’s best to just remove that one and work with new canes.

If you end up with a plant that wants to grow beyond its support structure, you’ll need to prune it back each year to keep it in check. Just snip the tall cane above the uppermost tie in front of a five-leaf leaflet.

Secure

Now for the fun part. This process is called training and tying in.

Grab some twine or garden tie wire. I like to use green twine because it blends in.

Garden tie wire is coated wire that holds its shape and it’s so easy to work with. It’s useful in a lot of gardening applications but especially if you plan to do a lot of rose training.

You can find a 32-foot roll from Amazon.

This should be plenty to train more than one rose in a season, or your most prized specimen over the course of a few years.

You’ll also need a knife, wire clippers, or something else to cut the ties with.

Hold the first stem where you want it and loosely tie it in place with the twine or tie. Do this by wrapping the tie around the structure and then tying a knot around the stem.

You might want to recruit a second pair of hands to help when you’re just starting out.

Don’t wrap the tie all the way around the stem. It should only go around the exterior of the structure and the exterior portion of the stem where it doesn’t come in contact with the structure.

You need to add a tie every two feet or so, unless the stem is particularly woody or doesn’t want to stay in place – and if that’s the case, it might really be in your best interest to cull that cane and move on.

Tie in the rest of the canes, maintaining an open layout so there’s plenty of room in between each and so they spread out across the entire structure that you want to cover. You never want canes to be touching each other.

The amount of space allowed between the canes depends on your preference and the sort of structure you’re training your plant to grow on.

A trellis has a lot less room than a wall covered top to bottom in support wires does, for example. A narrow beam is going to have less space than a large column, and so on.

Next, if you have branches coming off of the canes, tie those in as well. You generally want to train these at a 45- to 90-degree angle from the cane to create an open shape and give the plant lots of room to produce flowers without crowding.

Again, this is more difficult on a small trellis or obelisk than it is on a large trellis or a wall, and you might just want to leave the branches free to do their thing depending on what you’ve selected.

You’ll need to train new offshoots every year and you’ll need to tie in any new growth at the tip of the main canes once it grows a foot or two from the previous tie.

There’s no need to tie in any new canes unless you decide you need a new one to fill in any empty space. You can also start a new cane if an existing one dies. Otherwise, cut back any new canes that try to join the party.

Climb to Greater Heights

Training a climbing rose isn’t a challenging job once you have your support element in place and a plan of action. In fact, the hardest part is trying to avoid being cut to ribbons by those prickles – unless you’ve picked a thornless cultivar!

What are you encouraging your roses to climb? What cultivar are you growing? Let us know in the comments section below!

If you’re looking to take your rose garden to the next level, we can help. These guides might be just what you’re looking for: