Oncidium spp. (syn. Odontoglossum)

Are you up for a growing challenge? Have you mastered the art of raising Phalaenopsis orchids? Then it’s time to check out Odontoglossum orchids, also known as tiger orchids.

Native to high altitudes in the Andes in South America, these orchids are renowned for their big, vibrant blossoms that can last for months.

They’re also known for being a bit challenging to grow because they thrive in conditions not typically found in most homes.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Don’t let that intimidate you, though, it’s not impossible and imagine how good you’ll feel when your orchid is in full bloom in all its glory.

Additionally breeders have created a number of adaptable hybrids and cultivars that are much easier to care for.

By the time you finish this guide, you’ll be an expert. Here’s what we’ll go over to make that happen:

What You’ll Learn

Before we talk about how to cultivate these orchids, we need to clear up some terminology.

I know we often call them Odontoglossum, but that’s not quite accurate. They might be classified that way, but they might not. Weird, right? Let’s discuss.

What Are Odontoglossum or Oncidium Orchids?

Odontoglossum is a mouthful, so it helps to break it down.

Odonto is Greek for tooth, and glossa is Greek for tongue. Put them together, and you have “tooth-tongue.”

This is a reference to the fleshy little lumps found on the upper surface of the lowermost petal, which is known as the labellum.

Now that you know what the name means, you can forget about it.

Orchidists and botanists have been engaged for years in a fiery debate over how to classify these plants. Well, fiery for botanists, which is probably more like a polite conversation backed by scientific research and excellent reasoning than an all-out argument.

For decades, many orchidists have been campaigning for the reclassification of the Odontoglossum genus.

Since the early 2000s and as recently as 2016, the genus has been undergoing significant reorganization. It used to be that Odontoglossum species and Oncidium species were separate genera, despite the plants looking similar.

The former grows in cold regions at higher elevations, while the latter grows in warmer regions at lower elevations.

Now, they’re all classified together in the Oncidium genus, and those formerly classified as Odontoglossum are simply referred to as cool-weather or cool-growing Oncidium.

You might also see the new grouping referred to as the Odontoglossum alliance or the Oncidium alliance. The original species in the Oncidium genus are referred to as lowland or warm-growing Oncidium.

It seems like sellers haven’t caught up with the update, so you’ll sometimes find these sold under their original name, and a lot of people continue to refer to them that way. Even some orchidists refuse to accept the reclassification.

These orchids are sympodial, which means that the growth emerges from a horizontal rhizome in the soil rather than a single vertical stem like a Phalaenopsis.

They have flat, oval pseudobulbs from which one to three leaves emerge. As you might have guessed, they can grow as terrestrial orchids, but they’re typically epiphytes.

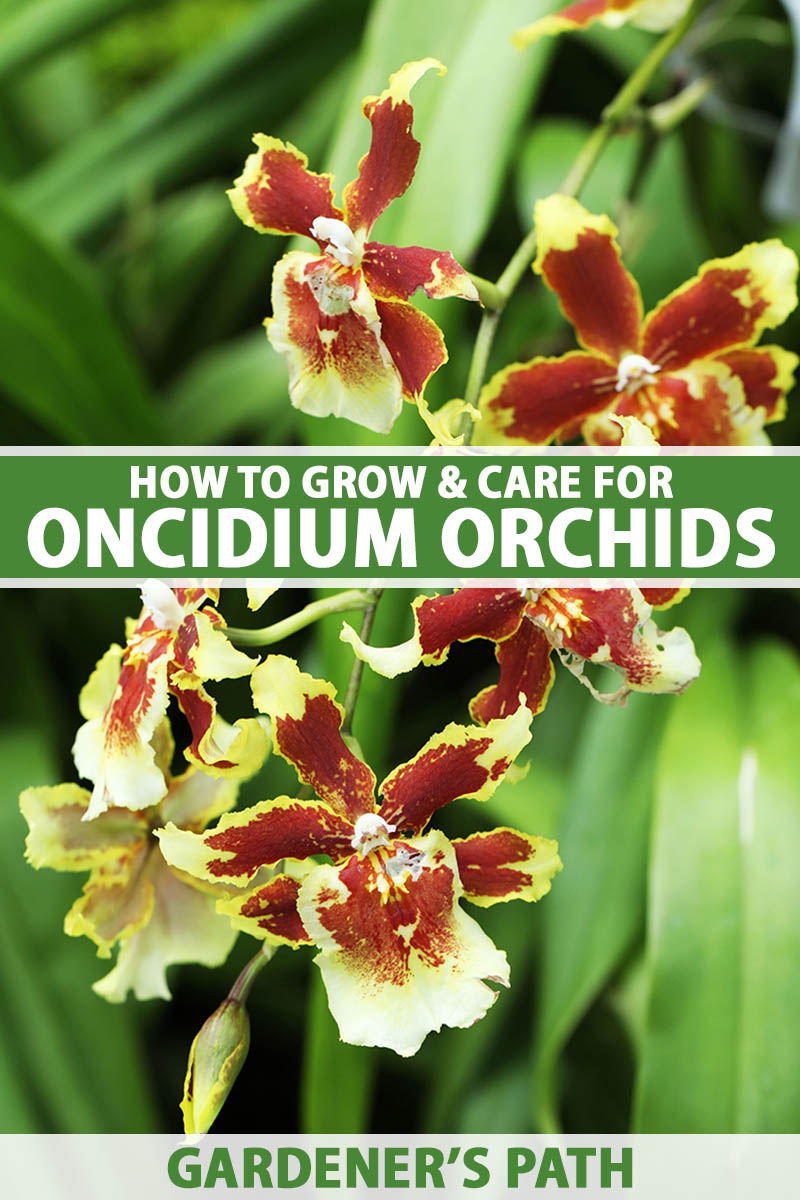

The showy flowers, which can be white, pink, red, purple, or any combination of those colors, typically emerge in the fall or winter, though a few species bloom in spring. Most species have dark speckling on the flowers, which can resemble the stripes on a tiger’s coat.

The blossoms are held on a flower stem that extends from the pseudobulbs, and each pseudobulb will form just one flower stem.

At the top of the stem are multiple flowers, each with three sepals, two petals, and a column and lip at the center. After the blossoms drop, that pseudobulb will never flower again, but new ones will form to take its place.

If you’ve never heard of pseudobulbs before, you can learn all about them in our guide.

In a nutshell, a pseudobulb is a stem-like growth at the base of the plant that stores water and nutrients.

Cool-growing Oncidium orchids are generally between one to four feet tall, depending on the species, though there are more compact hybrids available.

Cultivation and History

These plants grow indigenously across Central America and western South America from sea level to well over 8,000 feet.

They are generally hardy in Zones 7 to 10, depending on the species.

The plant was first identified by Westerners when German naturalist and explorer Friedrich Heinrich Alexander Baron von Humboldt found a specimen in Venezuela in 1799 that we now know as O. epidendroides.

It was sent to England for identification, and many other new species followed, as they were discovered by other explorers in the region.

The genus was named in 1816 by German botanist Karl Sigismund Kunth, who explored and studied the indigenous plants in the Americas.

In 1835, the first Odontoglossum bloomed in England to much fanfare when a specimen from Guatemala of the species O. bictoniense burst forth. This species rapidly became a favorite among collectors and plant breeders.

Breeders and home growers also focused on O. cordatum, O. crispum, O. harryanum, O. pulchellum, O. rossii. Today, many hybrids are cultivated from O. crispum and O. rossii.

Oncidium Propagation

It’s entirely possible to propagate orchids from seed if you’re adventurous. Our guide explains the process.

Division is also technically possible, but it’s challenging and best left to those with a lot of experience. Most of us will take the easy road and purchase our first plants.

When you bring your plant home, resist the urge to put it in a larger container.

Over-potting is a quick way to kill tiger orchids because they are extremely sensitive to growing in an overly large pot, which can contribute to root rot.

When you bring yours home, you can leave it in the existing container for another year or two.

How to Grow Oncidium Orchids

As I mentioned, these orchids have a reputation for being a little bit of a challenge to grow.

But, honestly, if you were used to the perfect climate of perpetual spring, you’d probably be a little annoyed if someone tried to make you live anywhere less idyllic.

The first matter you need to sort out is location. Cool-weather Oncidium plants need bright light, but they absolutely must stay cool, which can be tricky because often brightly lit areas in the home are also the warmest.

Avoid west-facing windows because of the amount of heat. East-facing windows will work, as will south-facing windows covered with light-filtering curtains – not sheer curtains – assuming you’re not in a very hot climate.

In very warm climates, you’d be better off keeping the plant away from any windows and providing supplemental lighting instead. Find a grow bulb that is low to medium light or one that is dimmable, and place it about 36 inches away from the plant.

This full-spectrum grow bulb available via Amazon has always worked well for me and you can put it in a conventional fixture so you don’t have some ugly grow light hanging in your living room or bedroom.

These plants grow natively at the edges of forests in “bright shade,” which may sound contradictory, but the shade under trees next to a meadow and the shade under trees in the middle of a forest is different.

Try to keep this in mind when choosing supplemental lighting or picking a spot in your home.

As I have mentioned, one of the main challenges of growing these orchids is that they require cool temperatures.

These plants should be kept consistently under 75°F. Healthy plants can tolerate brief periods warmer than this, but not for long.

At night, temperatures should drop to around 55°F. Any warmer than this, the plant will probably not thrive.

Most species can tolerate temperatures a bit below this range but will die in temperatures above 75°F. They also can’t tolerate freezing temperatures, so you need to keep the plants right in that sweet zone.

When you repot your orchid, note whether it’s an epiphyte or terrestrial.

Terrestrial types can grow in any loose, rich potting mix. Epiphytes need to be potted in orchid bark. Pure bark will work, but a medium with a little charcoal, lava, perlite, and/or peat is better.

You can find an excellent mix with moss, bark, perlite, and lava rock, available from rePotme in mini, junior, and standard bags via Amazon.

Whatever you use, a medium with a pH between 6.0 and 6.8 is ideal, and most potting mixes will be in this range unless they specify otherwise.

With some orchids, you can get away with growing them in a standard pot, but you need to use a slotted orchid pot with cold-weather Oncidium.

Feel free to place the pot inside a more decorative one, but a slotted container is essential when growing sensitive plants like these.

You can also opt to mount them on wood, wire, or something similar. In fact, I would recommend you mount your plants if you’re familiar with this growing method.

It’s hard to overwater them this way, and it more closely mimics their natural habitat. Your only concern is keeping the substrate as moist as a well-wrung-out sponge.

Next, we need to talk about water. These plants like lots of water, but the substrate must drain quickly and thoroughly.

They also need good quality water. That doesn’t mean you need to buy them the premium bottled stuff, though it wouldn’t hurt, but don’t use municipal water.

You can use filtered water, rainwater, or buy distilled water – ideally you want it to have a pH between 6.0 and 6.8.

The substrate should never be allowed to dry out, but it shouldn’t stay soggy and wet, either. In their natural habitat, these orchids receive consistent moisture year-round.

Once the pseudobulbs start to shrivel and wrinkle a little, they’re telling you they need moisture. You can learn more about watering orchids in our guide.

These orchids like a humidity level of between 55 and 80 percent. A lot of homes are drier than this, so use a humidifier or keep plants in the bathroom if it has the right light and temperature.

You can also group plants together to increase the ambient humidity around them.

Feed every other week during the spring and summer and weekly during the winter. If you are keeping your plant primarily in bark, it will need a stronger formulation than those grown in soil.

For a bark mix or soil, use something like a 3-1-2 NPK. For pure bark, use 6-2-4 or similar.

Liquid Indoor Plant Fertilizer

Leaves and Soul makes a 3-1-2 food for houseplants that you can find in an eight-ounce bottle at Amazon.

Growing Tips

- Grow in bright, indirect light and cool temperatures of under 75°F during the day and around 55°F at night.

- Provide humidity between 55 and 80 percent.

- Grow in a bark or bark mix.

Pruning and Maintenance

Most new orchids you purchase from the store come in a four- or five-inch pot. Leave your specimen in this for the first year.

Then, you’ll need to replace the substrate every year and repot into a larger container when necessary.

The best time to repot or change the substrate is in the spring or fall.

Remove the plant from its pot and gently knock out all of the substrate. Examine the roots and clip off any that are mushy, broken, or dead.

Hold the roots in the new pot and gently fill in around them with fresh substrate. Firm the substrate around the roots so that they are packed enough that you can lift the plant by the stem, and the pot won’t fall away.

When you start to see a lot of roots coming out of the slots in the pot, this is a signal that it’s time to go up a pot size.

If you have the plant mounted, you will need to remove the old substrate every year or two and replace it, increasing the size of the base slightly.

If your plant is mounted, it will typically be in a moss or bark substrate that is held together with mesh, string, or similar. You will need to replace this every few years as it breaks down, as well.

You need to replace the substrate periodically for potted plants, as well, because salts will build up from municipal water and fertilizer, and the substrate will break down over time.

You don’t need to repot the orchid, just remove the old substrate and replace it with new.

Some species will rebloom regularly every 10 months or so, regardless of what you do.

Others need to be exposed to temperatures about 10 degrees lower than normal for a month or so to encourage flowering. For more tips and the full run-down, check out our guide.

Oncidium Hybrids and Species to Select

As I mentioned, there are a number of modern cultivars and hybrids that are a bit less fussy than the species plants. Let’s look at a few stand-outs.

Cambria Hybrids

If taking care of Odontoglossum orchids feels overwhelming, look for O. x cambria hybrids.

They’re a little easier to grow in that they won’t give up the ghost if you don’t keep their growing environment just perfect.

Cambria is the name for various hybrid crosses between plants in the former Cochlioda, the former Miltonia, the former Odontoglossum, and Oncidium genera.

While they weren’t included in the original hybrids, modern Cambrias can also include plants in the Brassia genus.

Charles Vuylsteke, a grower in Lochristi, Belgium, bred the first Cambria out of Cochlioda, Miltonia, and cool weather Oncidium in 1911. The resulting bright red and white flowered plant was named O. x vuylstekeara in honor of the breeder.

Unlike other cool-weather Oncidium varieties, many of these hybrids bloom every nine months rather than annually.

The appearance of the plants is very diverse – with a variety of different leaf sizes and shapes, and flower colors and sizes.

Some people refer to any Oncidium alliance hybrids as Cambria, but now you know better.

Equitant

Equitant or O. x tolumnia orchids are smaller than your typical Oncidium alliance specimen.

They rarely grow more than eight inches tall and may never need anything larger than a four-inch pot.

The spring flower spike can be up to 18 inches long and come in colors that are unusual for orchids such as lavender, orange, pink, brown, burgundy, white, cream, and yellow.

These orchids tolerate warmer temperatures – up to the high 80s during the day and mid-60s at night.

Nobile

O. nobile is a fairly common species on the market, and that’s surely because of its flower stalks, which have clusters of up to 100 highly fragrant blooms.

They flower in the spring for weeks and weeks with blossoms in a wide range of colors from white to deep purple or red.

Managing Pests and Disease

Despite their fussy reputation, these orchids aren’t particularly troubled by pests.

You might see aphids or spider mites. Both of these sap-suckers use their mouthparts to extract the sap of orchids and many other houseplants.

Both can be eliminated by spraying them off with a strong stream of water and then treating plants with insecticidal soap.

The only disease to worry about is root rot. It can be caused by the fungus Rhizoctonia solani, but it’s usually caused by drowning the roots in too much water.

Orchids are notorious for being susceptible to root rot, and Oncidium species are even more so. You absolutely must ensure you don’t overwater, and you must grow your plant in a well-draining medium, like bark in a pot with drainage holes.

You should also be sure to regularly replace the growing medium because it will break down over time, reducing the amount of oxygen that can reach the roots.

Learn more about potential orchid problems and how to deal with them in our guide.

Best Uses for Oncidium Orchids

Most people opt to grow their orchids in pots, and they look lovely that way.

The long-lasting flowers and low-light tolerance make them perfect as a display on dining tables, bookshelves, coffee tables, and desks.

But they also grow well mounted on something like wood or mesh. Not only does it make for an interesting display, but it reduces the chance of the plant contracting root rot.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Evergreen epiphytic or terrestrial sympodial orchid | Flower/Foliage Color: | Bicolored, orange, pink, red, white, yellow/green |

| Native to: | Central and South America | Tolerance: | Low light for short periods |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 7-10 | Soil Type: | Orchid bark or bark mix |

| Bloom Time: | Winter or spring | Soil pH: | 6.0-6.8 |

| Exposure: | Bright, indirect light | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Time to Maturity: | Up to 5 years | Uses: | Container-grown or mounted houseplant |

| Planting Depth: | Same depth as previous container | Order: | Asparagales |

| Height: | Up to 4 feet, depending on variety | Family: | Orchidaceae |

| Spread: | Up to 2 feet, depending on variety | Tribe: | Cymbidieae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Subtribe: | Oncidiinae |

| Maintenance: | Moderate | Genus: | Oncidium (syn. Odontoglossum) |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, spider mites; Root rot | Species: | Blandum, constrictum, cirrhosum, gloriosum, harryanum, nobile, odoratum, tenuoides, tripudians, hybrids |

The Orchid With Teeth

Odontoglossum, Oncidium, Oncidium alliance, tiger orchids – whatever you call them, they’re undeniably beautiful plants with long-lasting flowers in striking colors.

Are you running into any problems growing yours? Maybe having trouble encouraging it to rebloom? Let us know in the comments and we’ll see if we can help.

Interested in more information about growing orchids? If so, have a read of these guides next: