Sanguinaria canadensis

It’s easy to think of a garden as a delicate place that’s free from danger… wimpy-sounding plant names like “baby’s breath” certainly don’t help.

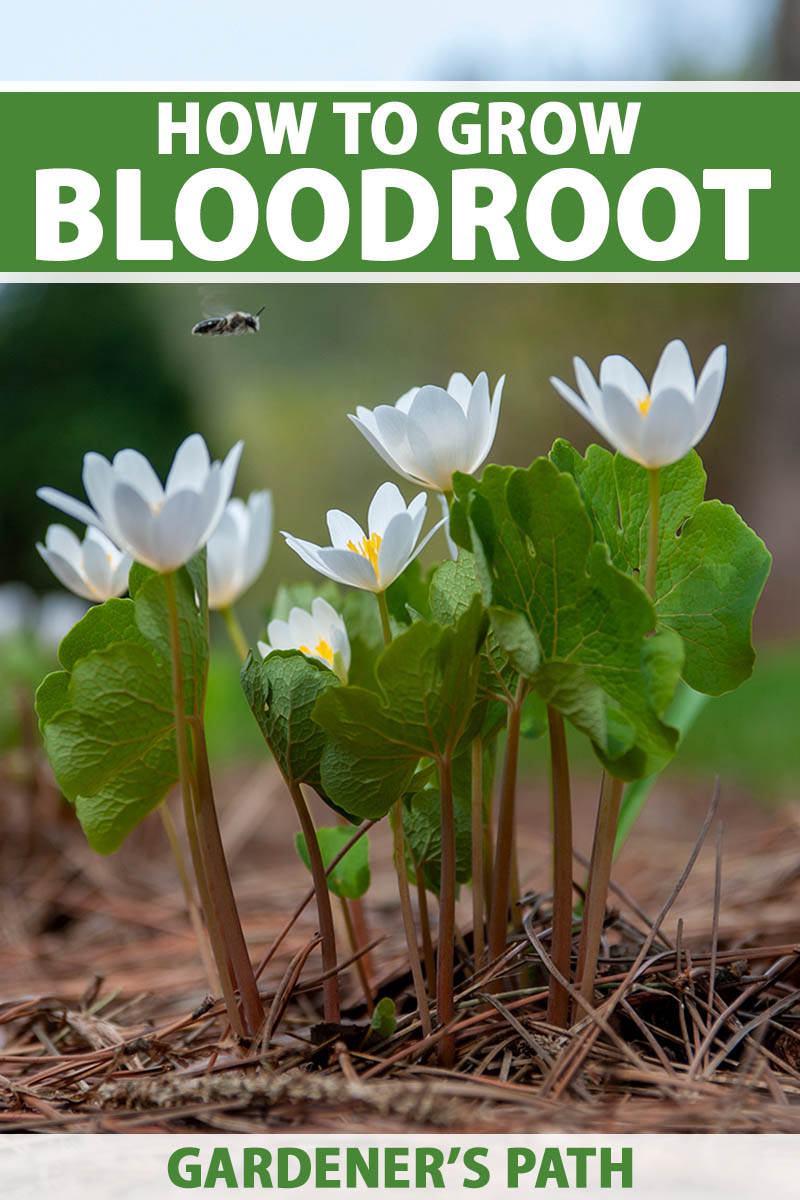

But if you’re trying to add an air of deadly elegance to your landscape, bloodroot is the plant for you.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Filled with toxic scarlet sap, Sanguinaria canadensis is a North American native that lives up to its name.

But aside from being a bit macabre, this plant has aesthetic beauty going for it – it flaunts palmate, deeply-lobed leaves and gorgeous white flowers, which are among the earliest to bloom in spring.

Combine all that with minimal maintenance, and bloodroot makes a pretty strong case for being grown in your garden. Court is adjourned!

Well… except it’s not, because you’ll need to know how to cultivate S. canadensis properly first. Hence, this guide. Bloodroot know-how, here we come!

Such an epic journey demands a map, of course:

What You’ll Learn

What Is Bloodroot?

Also known as puccoon, red puccoon, and bloodwort, bloodroot is a member of the Papaveraceae family, i.e. the poppies.

This family includes about 825 species, including the horticulturally famous bleeding heart and the criminally infamous opium poppy.

Hardy in USDA Zones 3 to 8 and native to the eastern half of North America, S. canadensis is distributed from Canada all the way south to Florida.

Across this rather large area, the plant can be found growing on damp forest floors, flood plains, and water-adjacent slopes. By slowly branching out from its root system to form large colonies, the plant can eventually cover substantial chunks of ground.

S. canadensis is the sole member of the Sanguinaria genus. Canadensis means “of Canada” in Latin, and this species name often applies to species native to the northeastern US as well, while the genus name comes from the Latin term sanguis, meaning “blood.”

The latter refers to the bloody-looking sap that flows through every part of the plant – and through the rhizomatous roots in particular.

S. canadensis produces vegetative stalks from its half-inch-thick, up to four-inch long, red-orange rhizomes in late winter or early spring.

Atop each stalk is a lone, two-inch-wide, white- or light pink-petaled flower with yellow stamens. Only living for about a day or two, the flowers close at night and during daytime temps below 46°F.

A single pale green, palmate, and deeply-notched leaf emerges tightly-wrapped around the middle of each stalk.

The foliage opens alongside the flowers and persists on the stalks after the flowers fade. Reaching up to nine inches wide, the leaves will senesce by midsummer as the plant goes dormant.

The flowers are pollinated by insects such as bees and flies, but their stamens can actually self-pollinate their own stigmas if it’s rainy, too cold, or if pollinating insects aren’t available.

After successful pollination, seed capsules will form where the flowers used to be, with each pod packing 20 to 30 red to black seeds that disperse in mid- to late spring.

Each seed comes with a fatty, protein-rich structure attached – an elaiosome – that is particularly tasty to ants.

Using their relative super-strength, ants move the seeds into their nests, munch on the elaiosomes, then dispose of the seeds in what’s essentially their nest’s dump.

This heap of composting organic matter protects the seeds until they germinate.

Cultivation and History

Along with pigmented sap, bloodroot contains sanguinarine: an anti-inflammatory and antiseptic alkaloid. Thus, S. canadensis has a history of usage in dye-making, medicine, and dental hygiene.

Native American tribes utilized the plant to dye fabric, baskets, and their skin.

Medicinally, they used bloodroot to treat conditions including, but not limited to: rheumatism, fever, pain, wounds, skin infections, insomnia, ringworm, ulcers, and coughs.

As they did in many different arenas, European colonists saw what Native Americans were doing and adopted many of those same practices.

According to the famed medical botanist and physician Willam P. C. Barton’s 1818 work “Vegetable Materia Medica,” bloodroot was found to have further applications as a stimulant, laxative, diaphoretic, and emetic… the last one being strong enough to expel worms from the stomach!

In the mid-1800s, S. canadensis had a brief stint as a purported treatment for skin cancers, fell out of use, and was later reutilized for that purpose by alternative medicine guru Harry Hoxey from 1920 to 1960.

After a forced shutdown by the FDA in the United States, Hoxey reopened his “Hoxey Therapy” clinic in Tijuana, Mexico… which, as of this writing, is still in operation today, despite no scientifically backed evidence for the safety or veracity of these treatments.

Today the plant is used in dye-making, and in dental products as an antiplaque agent.

Research pertaining to its potential for combating cancerous tumors is ongoing. The plant appears on the United Plant Savers “At-Risk” list – with a score of 47 out of 94 at the time of this writing – due to habitat loss and over-collection.

A Note of Caution:

Despite all the above historic and modern-day usages among some, I say this: for the love of all you consider holy, please don’t use this plant for anything beyond ornamental use.

It irritates the skin upon application, damaging blood vessels and causing disfigurement. Ingesting bloodroot can cause nausea and vomiting, a loss of consciousness, or even death via heart failure.

When comparing the pros and cons of potential human consumption, it’s not even close… and I wouldn’t allow your pets or livestock to take a nibble, either. Bloodroot is moderately toxic to dogs, cats, cows, and horses.

Propagation

To propagate bloodroot, you have a few options: from seed, by root division, or via transplanting.

Regardless of the method chosen, make sure to wear gloves when handling any part of this plant and wash your hands afterwards.

From Seed

You should probably save this one for when you actually have a bloodroot of your own to gather seeds from. I wouldn’t go foraging for any, for conservation reasons.

For those with S. canadensis already in your garden, take some cheesecloth or other gauzy material and loosely tie it like a pouch around young seed pods in early spring.

Upon opening in mid- to late spring, the pods will drop their seeds into the material instead of on the ground.

Any fresh seeds caught in the pouch should be planted immediately – sow them a quarter-inch deep and an inch or two apart in partially shaded, highly fertile, and well-draining soil with a pH of 5.5 to 6.5.

Have some dried, ethically sourced seeds on hand and you’re gardening in USDA Hardiness Zones 3 to 8? Sow these in the fall to naturally stratify outdoors.

Whenever you’re planting, moisten the soil, and then cover the planting area with two to three inches of pine or leaf mulch.

Continue to keep the soil around the seeds moist – germination should occur the following year after a naturally-occurring period of cold-stratification.

Via Division

During dormancy in fall or early winter, you can dig up mature bloodroot rhizomes and divide them into two-inch sections with a sterilized blade, ensuring that each piece has at least one bud attached.

In garden soil that’s similar to what you’d use for growing seeds, plant the rhizomes one to two inches deep with the buds facing up, spaced at least six inches apart.

Cover the planting area with two to three inches of pine or leaf mulch, and maintain soil moisture.

If you can’t plant the divided rhizomes right away, wrap them in wet paper towels and keep them refrigerated until it’s planting time.

Via Transplanting

But perhaps you’ve acquired a potted-up bloodroot from a vendor or nursery, and you need to put it in the ground.

First, you should gently tease the plant from its container.

Next, in a plot of that optimal garden soil mentioned earlier, bury the rhizome an inch or two deep, with the vegetative growth sticking up.

If you have multiple plants, space them at least six inches apart.

After setting a transplant in place, cover the root zone with mulch, and water it in.

How to Grow

Before you can make a claim as metal as “I grow bloodroot!” you gotta know how.

First and foremost, the optimal location for S. canadensis to thrive must be situated somewhere in USDA Hardiness Zones 3 to 8.

Within this ideal range, bloodroot should receive partial to full shade exposure. You’ll also want to keep it in a protected spot – even a mild breeze can knock the petals off the flowers.

The proper soil for bloodroot must be well-draining and fertile, with a pH of 5.5 to 6.5.

The soil around the plants must be kept moist, so water whenever the surface feels dry.

Ideally, if you choose a naturally moist and well-draining site from the get-go, it’ll save you a lot of effort on the irrigation front.

In order to satisfy the above fertility requirements, you should add some organic matter such as compost or well-rotted manure – a couple of inches worked into the soil each spring should do the trick.

Applying a complete, organic fertilizer alongside the humus will help combat nutrient deficiencies.

Hoss Tools Granular Fertilizer

A solid product for the job is this granular, OMRI-certified, 5-4-3 NPK fertilizer from Hoss Tools, available on Amazon.

Growing Tips

- Partial shade to full shade exposure is optimal.

- Make sure the growing site is protected from wind.

- Water whenever the surface of the soil feels dry.

Maintenance

Thankfully, this wildflower is pretty lax in its maintenance requirements.

S. canadensis can self-sow pretty easily, so you may have to dig up and pull or transplant any bloodroot colonies that spread beyond their bounds. Don’t forget to wear gloves!

Year-round, you should ensure that your bloodroot plantings are kept protected by a two- to three-inch layer of mulch.

Shredded leaves or pine straw will retain moisture and regulate soil temperature without potentially suffocating plants like heavier mulches may do.

Cultivars to Select

Whether it’s the standard species or a double-petaled cultivar, you’re probably jonesing for some bloodroot to plant right about now.

But before you go buying a specimen or seeds from any old vendor, you should definitely keep its threatened status in the wild in mind.

Because wild populations of S. canadensis have been reduced significantly in recent years, it’s important to only purchase from reputable sources of cultivated bloodroot.

Treat it like the opposite of salmon: if it comes from the wild, then it ain’t sustainable.

Additionally, you shouldn’t collect these plants from the wild yourself. Taking divisions or seeds from your own garden or acquiring them from a friend is acceptable, assuming that your pal was sustainable about it, anyway.

As if the flowers of a regular S. canadensis weren’t pretty enough, a double-flowered form of bloodroot exists as well!

Going by the synonymous names of ‘Plena,’ ‘Multiplex,’ and ‘Flore-pleno,’ this cultivar has an inner ring of petals where the stamens would normally be… meaning this infertile variety won’t spread via seed.

It’s beautiful enough to have won an Award of Garden Merit in 1993 from the UK’s Royal Horticultural Society!

Managing Pests and Disease

There are a few critters and pathogens who pose a threat to a bloodroot’s health. I suppose you could say that they’re “out for blood”…

Herbivores

For the following plant-eating mammals, S. canadensis isn’t their preferred meal, due to its bitter taste and toxicity in large quantities.

But beggars can’t be choosers, so don’t be surprised if these guys feast on your bloodroot when little else is available early in the season.

Deer

A perimeter of deer fencing around your property is the best way to keep these conniving cervids from breaking in and munching on all your hard work.

Should deer somehow infiltrate your yard, sprays of deer repellent on susceptible plants such as bloodroot will discourage feeding.

Our DIY deer fencing guide, and these six-pound tubs of granular deer repellent – sold by Enviro Pro on Amazon – will aid you in your deer deterring.

For further tips, check out our deer control guide.

Groundhogs

Also known as woodchucks or whistle-pigs, groundhogs will emerge from winter dormancy, mate and give birth, and then feast on your garden with their children… if given the opportunity.

The above-mentioned deer fencing will halt any aboveground woodchuck movement, but you’ll have to add two feet of subterranean fencing to keep any tunneling whistle-pigs out.

Install it in an L-shape at the base, with one foot of material sunk straight down and another foot jutting out at a 90-degree angle away from the garden.

Many different substances can act as groundhog repellent when placed around your plants and the garden perimeter, such as ground black pepper, blood meal, hair clippings, and predator urine.

Humane catch-and-release traps baited with fresh fruits or veggies can be used if you’re looking for a more aggressive approach – make sure to place them around susceptible plants or known burrow entrances.

Any captured groundhogs should be relocated to a field or woodland area at least 20 miles away from where they were caught, without violating any local regulations.

Turkeys

A wild turkey that shows up on your property can be a novelty at first. But after you witness the damage they can do to your garden, you’ll want them gone asap.

A scarecrow, fake predator, or actual dog in your garden can scare off turkeys pretty quick.

If your mutt is unleashed, stay close by so that you can call off Fido before his predatory instincts kick in and dog-on-turkey combat ensues.

Spraying turkeys with hoses or motion-activated sprinkler systems will frighten them, as will loud noises.

For the latter, you can shake a coin-filled coffee can, turn on a bullhorn’s siren, bang pots and pans together… have fun using your imagination!

Slugs

Slugs tend to strike in damp and shaded conditions, making bloodroot the perfect target.

These shell-less mollusks use their rasping, file-like mouthparts to feed on plant tissues, resulting in irregularly-shaped holes in foliage.

Along with the feeding damage, slugs leave behind their trademark slime trails as a sign of their presence.

To rid your plants of slugs, go out at night with a flashlight, remove the pests by hand when you find them, and drop them in a baggie for later disposal.

For less hands-on control, place beer traps, diatomaceous earth, and/or copper strips around your S. canadensis.

Slugs also tend to hide whenever the sun comes out, so remove any nearby hiding spots such as rocks, plant detritus, or shade-providing plants if you can.

Disease

Infections are more likely to occur in less-than-sanitary conditions.

Therefore, you’ll only want to use clean soil and disease-free S. canadensis specimens, and be sure to sanitize your gardening tools.

Additionally, the fungal conditions that we’ll quickly cover here tend to infect plants sitting in excessively wet soil, so make sure to provide ample drainage and avoid overhead irrigation.

Alternaria Leaf Blight

Caused by the fungus Alternaria dauci, Alternaria leaf blight is primarily noticeable on a bloodroot’s foliage.

Beginning with chlorosis and small necrotic spots, these grow in size as the condition progresses. Eventually, it could culminate in severe leaf loss, reduced root growth, and diminished seed production.

You should remove infected plantings if symptoms become apparent. There is no recommended treatment or cure.

Botrytis Gray Mold

When Botrytis cinerea fungi infect plants, the gray mold reveals itself as thin, grayish mycelium that appears on plant tissues, which contains spore-producing conidiophores.

Additional symptoms include spotted and decaying shoots, along with stem cankers.

Burn or otherwise dispose of infected plants so the condition doesn’t spread. Fungicides aren’t recommended for treating this petal-attacking disease.

As for prevention, be sure to deadhead any faded flowers and remove fallen plant detritus to prevent gray mold infections. Certain fungicides may be applied preventively as well.

Pythium Root Rot

This condition is caused by various species of Pythium, including P. irregulare, P. aphanidermatum, and P. ultimum.

Regardless of the exact causal species, infections lead to stunted growth, dead leaf tips, and water-soaked roots, resulting in an unhealthy, sorry-looking bloodroot.

Along with overwatering, overfertilization can also lead to Pythium root rot. You’ll want to remove any symptomatic plants and infected soil.

Fungicides labeled for Pythium control will provide the best results when applied preventatively.

Best Uses

The way that bloodroot colonizes an area via its seeds and rhizomatous root system makes it ideal for growing en masse in your landscape.

Because it can handle partial to full shade, S. canadensis is a perfect candidate for woodland and shade gardens, too.

As one of the first plants to put forth leaves and flowers in the spring, bloodroot can be situated in the vicinity of other early-sprouting flowers such as crocus or daffodil for an aesthetic punch of early color.

Just as the early bird gets the worm, an early-growing plant gets the attention.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Herbaceous flowering perennial | Flower/Foliage Color: | White or pink-tinged/pale green (red rhizomes) |

| Native to: | Eastern North America | Tolerance: | Drought, dry soil, black walnut juglone |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 3-8 | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Bloom Time: | Spring | Soil Type: | Moist, fertile |

| Exposure: | Partial shade to full shade | Soil pH: | 5.5-6.5 |

| Time to Maturity: | 2-3 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | 1/4 inch (seeds), up to 2 inches (rhizomes) | Attracts: | Ants, bees, flies |

| Spacing: | 1-2 inches (seeds), 6 inches (divisions/transplants) | Uses: | Flower gardens, planting en masse, native gardens, shade gardens, woodland gardens |

| Height: | Up to 12 inches | Family: | Papaveraceae |

| Spread: | Up to 10 inches | Genus: | Sanguinaria |

| Water Needs: | Low to moderate | Species: | Canadensis |

| Common Pests: | Deer, groundhogs, turkeys, slugs | Common Diseases: | Alternaria leaf blight, Botrytis gray mold, Pythium root rot |

Give a Salute to Good Ol’ Bloodroot

Such an awesome plant definitely deserves respect. Maybe a strict, military-style salute is overkill, but for an ornamental asset like bloodroot, a laid-back flick of the wrist is the least you could offer.

Don’t forget about the botanical backstory of S. canadensis – it’s the perfect icebreaker for when you’re showing off your garden to visitors, but don’t quite know what to say next.

Now, you’re able to wow them with your knowledge!

Still have questions? Anxious to chip in your two cents? The comments section is wide open!

For information on other flowers that bloom in early spring, have a gander at these growing guides next:

What a great resource this is. Thanks for the info on this really cool plant!

But of course, Sara! I’m glad you enjoyed it!

What an interesting read! Thank you Joe Butler.