Forsythia is one of the earliest spring-blooming shrubs in USDA Hardiness Zones 5 to 8. It’s a tough bush that usually sails through winter unscathed.

However, sometimes a year comes along with record-setting chills and frequent snow and ice storms, often surprising us with a last blast in early spring, when the buds are awakening.

These freak weather flares can cause damage to plant tissue, undermining its ability to take up nutrients, and in severe cases, causing the tips of stems to die, and buds and flowers to freeze and wilt.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

In this article, we discuss how to recognize, manage, and inhibit cold damage to forsythia.

Here’s the lineup:

What You’ll Learn

Let’s begin with a chat about hardiness and growing zones.

But Forsythia Is Hardy, Right?

A plant’s hardiness is defined by the zones in which it can be cultivated. Forsythia is cold hardy to Zone 5, where winter temps can dip to -10 to -20 °F.

How can forsythia suffer cold damage if it’s grown in an appropriate zone?

Great question!

Growing zone parameters are determined by taking mathematical averages of past weather data.

However, as we remember from middle school math, there are both higher and lower numbers factored in to calculate these averages.

All of this means sometimes the temperature in a particular zone plummets below the average and exposes plants to chills beyond typical expectations.

The Effects of Cold and Freezing

Damaging cold snaps don’t just happen in wintertime. They can also surprise us in spring and fall.

The amount of harm they cause depends primarily upon three factors:

- Timing

- Precipitation

- Wind

Let’s discuss them.

Timing

During the winter, forsythia is dormant. On its hard, woody stems there are visible flower buds. Inside them is moisture-containing tissue.

A brief cold snap is unlikely to do harm, but a prolonged one can cause the moisture inside plant tissue to freeze, rupturing and destroying it.

The most vulnerable parts are the flower buds and stem tips, and only the arrival of spring will reveal the extent of the damage.

In the spring, the first warm days signal the end of dormancy, bursting buds, and a flush of foliage.

A dip in the mercury at this time can cause buds and freshly opened blooms to drop off. It can also shock fresh tip growth, causing it to wilt or die.

If a cold blast arrives prematurely in the fall, before the stems have hardened off for the winter, tender tissue – including next year’s buds – may be adversely affected. Unfortunately, the full scope of the harm won’t be evident until next spring.

Precipitation

As for precipitation, we have both ice and snow to consider.

A coating of ice puts stems at risk of snapping, especially when it’s windy.

Snow, however, can be advantageous when it falls during dormancy.

It acts like mulch, insulating roots, minimizing ground temperature fluctuations, and aiding in moisture retention.

And when it melts, it adds moisture to the soil, facilitating water and nutrient uptake.

Snow also offers root protection during a phenomenon called “heaving,” in which a shrub rises out of the ground during repeated episodes of freezing and thawing.

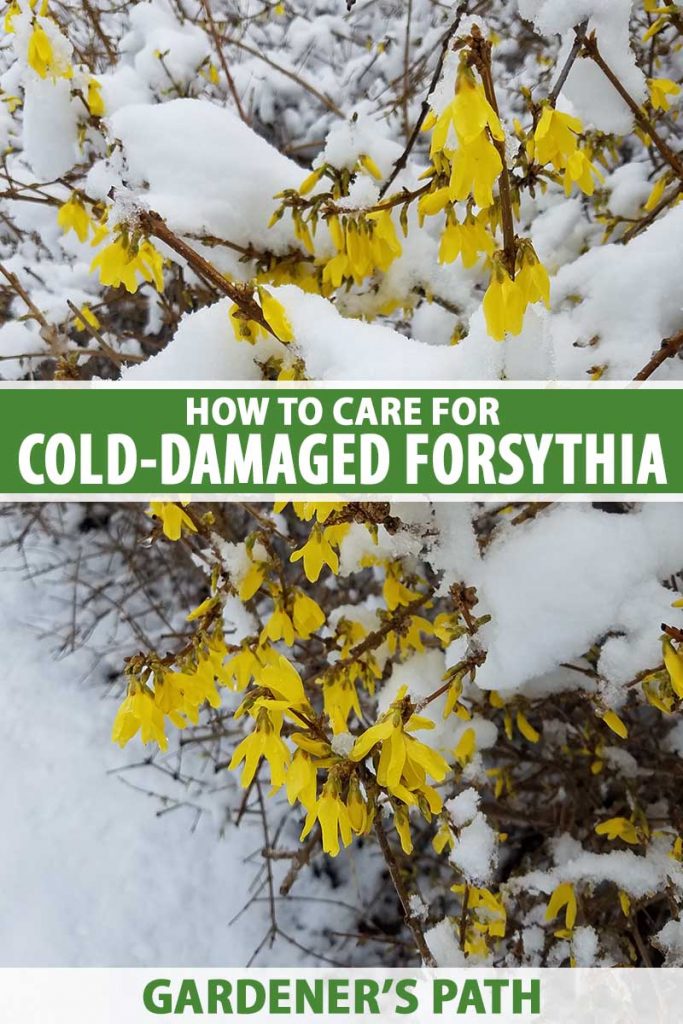

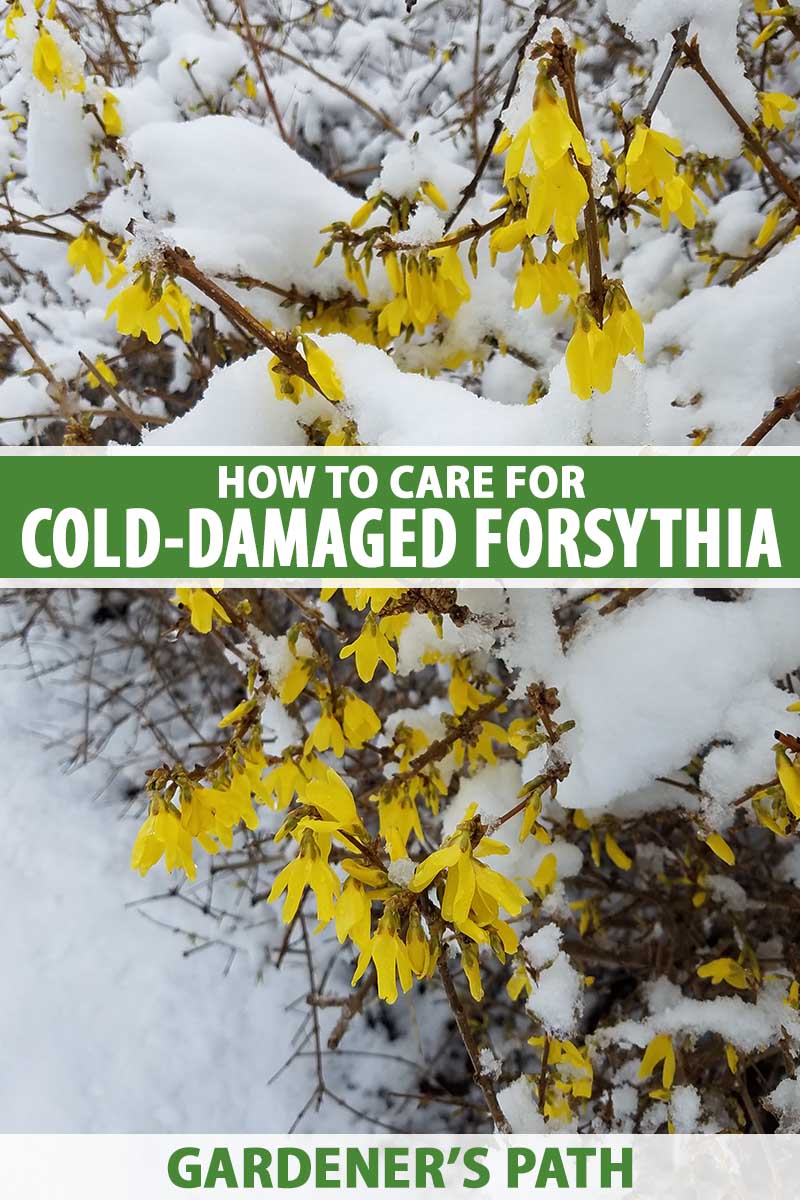

Often, when spring comes, you can tell just how deep the snow was during the winter by the condition of your shrubs.

Where branches were covered by lovely insulating white, they bloom better than those that remained fully exposed.

As good as it can be, there are times when snow is a problem, and this has to do with wind.

Wind

When bushes are repeatedly buffeted by cold wind gusts, stems begin to dry out. This drying of plant tissue is called “desiccation.”

In this state, a heavy accumulation of snow can cause breakage.

This is especially true of thin, twiggy top growth, the kind you can avoid with a good pruning regimen.

In the spring, stems affected by chilling winds may exhibit “bud kill,” or dead buds. They may also appear stunted and/or have dead tips.

And in cases where roots are exposed from heaving, wind exacerbates the problem by drying out these tender food and water transmitters, potentially killing the shrub.

Signs of Damage

Forsythia that is adversely affected by cold weather uncharacteristic of its appropriate growing zone may exhibit telltale signs, such as:

- Blackened or broken stems

- Brown, dry edges on flower buds, flowers, leaf nodes, or leaves

- Dead twigs

- Dead stem tips

- Droopy new stems

- Few to no blossoms

- Flower or leaf bud drop

- Flower wilting and premature drop

- Malformed or wilted leaves

- Mushy plant tissue

- Stiff, lifeless stems that produce no flowers or foliage

- Unearthed roots

Unless your forsythia suffers “winter kill,” in which all living parts succumb to the cold, a full recovery is likely, especially with a little TLC.

Shrub Rehabilitation Tips

Regardless of when the cold injury happens, it’s best to wait until dormancy breaks in the spring to make assessments and determine what action is needed, if any.

There are times when the cold may cause buds to drop before they bloom, or for blooming flowers to shrivel and fall prematurely.

However, if the first flush of spring foliage shows no signs of deformity, you may be in the clear and don’t need to do a thing.

If you find broken or discolored stems, as well as those that don’t bloom or grow foliage, removing them is a good place to begin.

Use clean pruning shears, loppers, or a pruning saw as needed to cut stems off at their points of origin.

This is how to grow healthy, long canes that bear an abundance of blossoms, as opposed to weak, twiggy ones that don’t.

We prune in the spring because soon after blooming, and often while the flowers are still attached, foliage sprouts, and sends up new canes that contain the buds for next year’s flowers.

This is what we refer to as blooming on “old” wood, or the growth from the previous year.

Pruning later in the growing season can leave you without fresh canes and few to no blooms next spring.

It’s best not to remove more than one-third of a shrub at a time to avoid shocking and possibly killing it.

However, if it seems to be completely dead with stiff, dry stems and no flowers or foliage, it’s worth cutting all of the stems as low as you can to try to rejuvenate it.

If the roots have been well insulated by snow, they may still be alive, and the jolt may just trigger them to send up new shoots. If you don’t see any signs of life by summer, call the bush a loss and dig it out.

In a case of “heaving,” the winter phenomenon we talked about in which repeated freezing and thawing cause uprooting, you’ll need to gently loosen the soil around the roots and settle the shrub back down again.

If there has been soil erosion, you may need to supply more to secure and cover the roots.

Once spring comes, there’s usually rain. But if there isn’t at least an inch per week, provide supplemental irrigation.

Cold-stressed flora benefits from consistent moisture for recovery. Just don’t overdo it – no soggy soil.

It’s a good idea to promote lush foliar growth by fertilizing recovering bushes in the spring. Use an all-purpose, slow-release granular product per package instructions.

Never fertilize at the end of the growing season, or you’ll end up with soft, weak stems that don’t have time to build strength and harden off before winter.

Shrubs that are stressed by adverse weather conditions are more vulnerable to pests and diseases than healthy ones, so it’s wise to rehabilitate ASAP.

Preventative Methods

In addition to knowing the signs of injury and how to restore affected foliage, there are proactive steps you can take to give your shrubs a leg up on weathering the worst.

Here are five:

- Plant in locations with shelter from wind, such as near building foundations and fences.

- Before the first frost of fall, water deeply at the soil level to allow stems to take up water and essential nutrients just prior to dormancy.

- Fertilize in spring with a well-balanced, slow-release fertilizer to stimulate healthy foliar growth.

- As summer draws to a close, place a two-inch layer of mulch over the roots to help minimize ground soil temperature fluctuations, inhibit heaving, and aid in moisture retention.

- Wrap dormant shrubs in burlap for added protection.

Burlap is an excellent protective fabric because it allows for good airflow, which is still essential, even in chilly weather. With poor circulation, foliage is more susceptible to fungal diseases.

Cover small bushes entirely and wrap the bundle with twine.

For larger ones, create a shelter using tall, sturdy stakes with burlap wrapped around them.

The top branches will likely be exposed, but even so, the overall warmth and wind resistance will be greater with perimeter coverage.

Biodegradable Natural Burlap from Burpee

Find biodegradable natural burlap from Burpee in 3-by-24-foot rolls.

A Good Prognosis

Temperatures that plunge suddenly, fluctuate wildly, and remain low for prolonged periods can cause harm that ranges from mild setbacks with snapped twigs and fewer blooms, to devastating cases of fatal winter kill.

Sometimes one shrub fails to survive a rough winter, while another sails through unscathed. This can happen because no two plants or their locations are exactly alike.

A host of differences may exist, such as:

- Age

- Health

- Height

- Variety

- Wind exposure

Overall, hardy forsythia that is grown in the appropriate zones is resilient and more likely to weather cold blasts than it is to fall victim to them.

How do you protect your forsythia from the winter chill? Let us know in the comments section below!

And for more information about growing forsythia in your garden, you may want to read these guides next:

- 7 Reasons Why Forsythia May Not Bloom

- How to Grow and Care for Forsythia

- How to Manage Forsythia Gall Disease

- 5 Common Causes of Forsythia Yellowing

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photo via Burpee. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock.