Tunnels and cold frames can only get you so far.

If you really want to extend your growing season and increase the number of different types of crops you can grow, it’s time to level up with a hotbed.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

I like to imagine that some gardeners centuries back noticed how hot a manure pile can get, and they had a lightbulb moment – or maybe an oil lamp moment?

That natural heat offers a darn good way to keep plants warmer during the cool months. And if you happen to have horses, chickens, or cattle, or know someone who does, it’s also pretty much free.

Of course, the process has been refined over time and there are modern tools you can use to make your hotbed even more efficient, but the fundamentals remain the same.

If you’re dreaming of fresh veggies in winter or having the ability to start your seeds earlier by a month or more, you’re going to love your new hotbed.

To help make your warm and burgeoning dreams a reality, here’s what we’re going to discuss:

What You’ll Learn

The process of building a hotbed isn’t that complicated and the time it adds onto your growing season is invaluable. Ready to heat things up? Here we go!

What Is a Hotbed?

If you’ve ever had a thriving compost pile, then you already know that decomposing matter generates heat.

A hotbed harnesses this heat to keep your winter crops warm and toasty. You can put any type of decomposing matter to work this way, but most gardeners stick with decaying compost or manure.

Some barns that support a lot of livestock will generate large manure piles.

If you walk past one of these piles, you’ll notice that the snow melts off faster and weeds are able to grow around the pile when they succumb easily to the cold just a few feet away.

That’s the magic of hot poop.

You could probably set a tray of seeds on top of a manure pile and have some luck, but to really harness the power of the decomposing matter, we usually contain it in some way.

This could be as simple as heaping a pile inside some chicken wire in your high tunnel. Or you could place a cold frame over a pile.

While having a hotbed doesn’t mean you’ll suddenly be able to grow tomatoes in your Minnesota yard in January, it does open up a ton of growing options.

Creating Heat

If you’ve ever established a healthy compost pile, then this part is going to sound pretty familiar. The best material is manure because it heats up really well, but you can also use “green” matter like kitchen scraps, garden waste, green leaves, and the like.

Whichever you choose, mix it with equal parts dry or “brown” matter. This could be dead leaves, straw, wood chips, and so on.

Combine your brown and green materials well and place them in a pile or inside the container you built for them. We’ll discuss your options there next.

If you have access to manure mixed with shavings from a barn or chicken coop on your property, or from a nearby neighbor, you’re in luck.

This is the perfect stuff to get you started. You don’t need to add anything because it’s usually already composed of the perfect mix of brown and green matter.

Building a Container

If you have a greenhouse or high tunnels, you’ll want to contain the heating material in something similar to a raised bed. This increases the amount of heat that will be generated, plus it keeps things nice and tidy.

A longer-lasting solution is to build a raised bed using cinder blocks, stacked stones, or bricks. If you don’t mind rebuilding your container every year or two, you can also use wood, logs, or hay bales.

Depending on the size of your greenhouse or tunnel, you’d need quite a large pile to create ambient heat in sufficient quantities.

A pile that takes up about a sixth of your floor space will raise the temperature inside the structure by a few degrees. But there are definitely more efficient ways to raise the ambient temperature for best results!

Most gardeners use their pile as a base underneath their plants, instead of using it to try and heat up the entire overall area.

To create a base, you’ll need to fill your frame with about two to three feet of manure at the bottom of the bed, and about a foot of gardening soil at the top for the plants. Sprinkle with water so the top two feet are moist but not soggy.

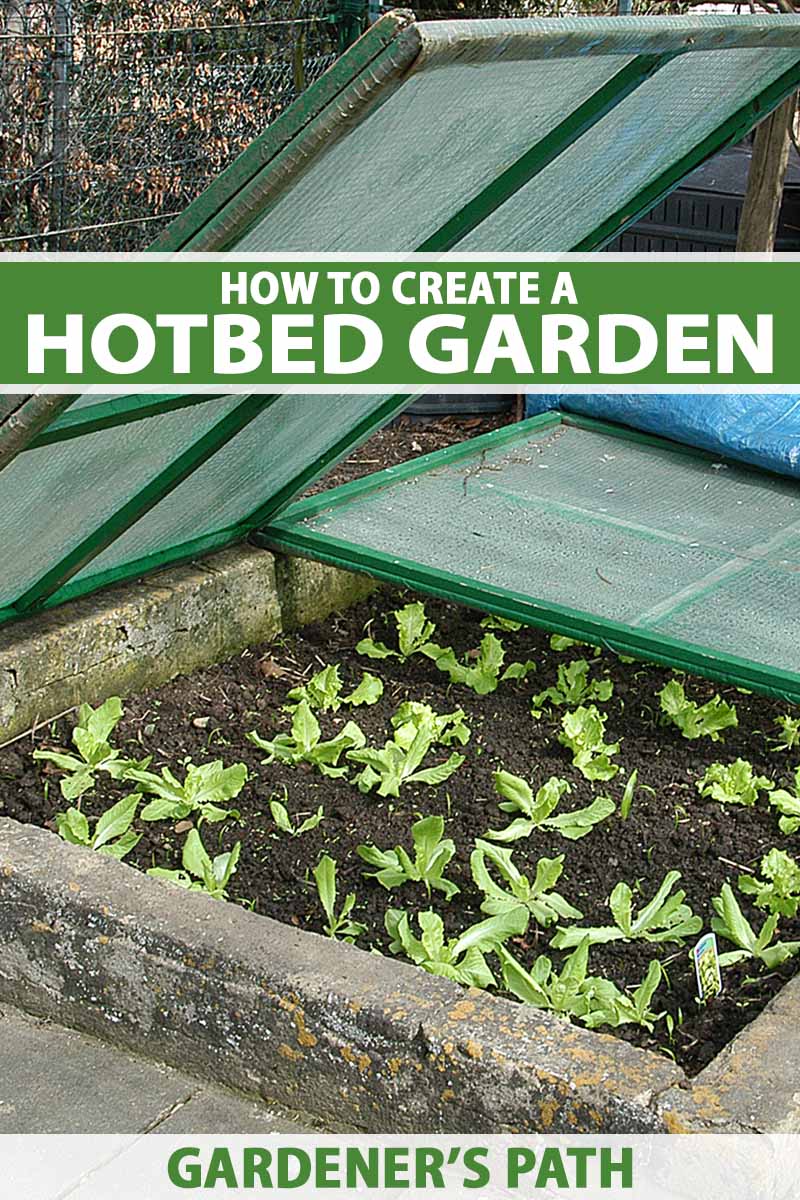

If you opt to put a cold frame over your hotbed, you’ll need to dig down approximately three feet and fill the hole with about 30 inches of your mixed material.

Place your cold frame over the hole and fill it with a foot of gardening soil. The soil should extend about six inches up the walls of the cold frame. Sprinkle with water.

At this point, heap straw or soil against the taller, back side of the cold frame as insulation. You can do this on the sides as well, if you like.

If you have raised beds that are tall enough, you can fill them with two or three feet of manure and a foot of gardening soil and then place low tunnels over the bed, but this option won’t hold nearly as much heat as a cold frame or plant bed in a greenhouse will.

Regardless of the method you choose, you’re going to let the pile heat up for a few days. Place plastic sheeting or a tarp over the bed for a day or two to really start the heating process.

If you don’t feel a distinct heat coming off your bed after a day or two, add some more water and adjust the quantity of brown or green matter as needed if your mix isn’t equal.

Eventually, your pile should reach a toasty 90°F of more, which you can check with a soil thermometer.

At this point, remove the plastic and allow it to cool a bit before placing your seeds or seedlings in the soil. How much you allow the bed to cool depends on the temperature range your plants can tolerate. Something around 60°F is ideal for most plants.

Before you plant anything, remove any weeds that might have started popping up. You never know when some sneaky seeds might hitch a ride in your compost or manure pile.

Using Your Hotbed

Keep a probe thermometer on hand because you need to keep a close eye on the temperature.

Cold-season plants such as spinach, miner’s lettuce, kale, beets, and radishes grow well in soil temperatures ranging from 55 to 65°F. Warm-season crops need temperatures about 10 degrees higher.

You can also plant root crops such as potatoes, turnips, and radishes in raised beds.

If you opt to plant something long such as carrots or some of the larger potatoes, you’ll need to make your topsoil layer at least six inches deeper, though a foot deeper would be better still.

Both cold- and warm-season crops will be fine if the temperature creeps up to around 85°F, but at that point, you should open the cold frame or door to the greenhouse to create a little ventilation.

Be sure to close everything up at night or you might be greeted by a sad sight in the morning.

Also remember that when it starts to become too warm, some cold-loving plants like lettuce might bolt.

It can be difficult to regulate the temperature using compost or manure, so you will need to check the temperature regularly and act quickly if things start to heat up too much.

If the temperature starts to drop too low, add a layer of plastic over the top of your bed and keep it in place until the bed comes back up to the temperature you’re aiming for.

Make sure the plastic doesn’t touch any of the plants. You can reuse tomato cages or garden stakes to prop the plastic up as needed.

You’ll need to replace your heating material annually. Toss the used stuff in your garden beds as compost unless you’ve had problems with soilborne fungal issues over the winter. If that’s the case, it’s probably safest to dispose of it.

You can also go the easier route of using heating cables, but you’ll need access to electricity if you want to use this method.

Heating Cables

Similar in effect to the method described above, you’ll be using heating cables to warm up a planting bed instead of manure or compost, placing them underneath your top layer of soil.

To install electric cables, lay down landscape fabric at the base of the frame. Attach the heating cables using string, twist ties, or wire. Follow the manufacturer’s directions for spacing, though about two or three inches is typical. Don’t cross any wires.

Add an inch-thick layer of sand and lightly water it. Now, add your top layer of garden soil.

You can find heating cables at many specialty nurseries or online from Walmart.

This 48-foot length of soil heating cable that would be perfect for warming up a larger raised bed.

Heat Things Up with a Hotbed

Old Man Winter, we’ve outsmarted you again! I’m going to enjoy fresh veggies in the winter and there’s nothing you can do to stop me! I mean, please don’t take that as a dare, though…

In all seriousness, you have to love a gardening solution that is so simple and so effective. You’ll never look at a pile of manure in the same way again!

What do you plan to grow in your hotbed? Give us all the details in the comment section below.

If you’re looking for other ways to extend your growing season, we have some guides that you might find useful, including:

I’m new at gardening, however it seems really comforting.

Enjoy your gardening Shikey!