Some fruit trees are highly susceptible to disease and pest infestation, such as stone fruits like peaches and plums, or apples.

Others, like the pomegranate, are far less likely to be stricken with serious diseases or ravaged by infestations. But there are a handful of pests and diseases to be on the lookout for.

Fortunately, most of these maladies will be visibly evident, as long as you’re paying attention – but how will you know what to look for?

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Read on to learn what signs and symptoms you can expect from a distressed pomegranate tree or shrub, and how to address problems when they arise.

What You’ll Learn

Planning Ahead

Even with the slightly lower likelihood that maladies might afflict your pomegranate plants in the first place, you’ll still want to take some preventative measures to support their health.

If you haven’t planted your tree or shrub yet, you should be sure to choose a location where the soil drains well. Soil that stays too wet, or that stays wet for too long, will harbor pathogens that can lead to infection.

If you’ve got an existing tree that is growing in soil with poor drainage, there are several ways to correct the issue, including installing drains, adding trenches to divert water, or if all else fails, relocating the tree.

You’ll also want to make sure you’re not overwatering. These plants have a deep taproot that can find buried moisture even in drought conditions, so you should only need to offer about one inch of water per week to mature trees during times of little rainfall.

Don’t underestimate the importance of the soil to overall plant health – it’s one of the keys to keeping your plants thriving. If you need more information on soil health, and how to address less than ideal conditions, read our guide.

Pruning is important for pomegranate plants, whether you choose to shape them into trees with a single leader or allow them to grow in their natural shrub form.

Crowded or dense plants can hold humidity, and dense branches and foliage may reduce airflow or light penetration, leading to conditions that can invite disease and infestation.

Without adequate pruning, many varieties of pomegranate can become large – some standards grow up to 30 feet in height and nearly as wide.

If they become overgrown, you may have a very dense, thorny shrub on your hands to try to treat, which can be very difficult.

One of the simplest ways to prevent issues with plant health is to frequently observe the condition of the plant.

Often, you’ll be able to see signs that indicate problems in advance, before they become severe. If multiple trees are growing in close proximity, you’ll want to be extra vigilant to prevent potential spread.

If you’ve had previous issues with pests and you want to bolster your plants’ defenses against reinfestation, you can introduce beneficial nematodes or attract beneficial insects such as green lacewings, praying mantises, and ladybugs.

Birds are also helpful, as they consume pest insects, and there are a number of ways to make your yard more inviting for them as described in this article.

There are only a few common pests and diseases that are known to affect pomegranates, and fortunately, many of these are relatively easy to mitigate.

Pests

Let’s take a look at the unwanted guests you might see perusing your plants first.

Herbivores

Pomegranates are a type of tree that most animals will pass up. The thick exterior of the fruit is enough of a deterrent that many avoid them entirely, choosing other easier-to-eat foods from your garden instead.

There is but one known herbivorous creature that can give you quite a hassle – the squirrel.

They’re cute, aren’t they? Hopping along, tiny fingers grasping at the railing of your porch, fluffy tails twitching behind them?

Cute, that is, until they decide the fruits you’ve been waiting on to ripen for six months look like a nice choice for breakfast.

Even more annoying, they’ll not only gnaw on the fruits to extract some of the seeds, but they’ll discard more than half after they tire of chewing the tough exteriors, leaving them to rot on the ground.

You’ll probably see crows or other larger birds picking at the exposed seeds left behind.

There are very few deterrents or methods available for barring access to squirrels; they’re generally able to chew through, climb over, or weasel their way into any defensive system you have spent time and money installing.

You can start with using mesh or paper barrier bags to wrap each fruit individually.

This can be extremely time consuming and a huge inconvenience, but once the pollinated buds begin to plump up, you can cover them. Be sure to tie the bags tightly closed.

You can find a 10-pack of reusable mesh barrier bags available from Amazon, but be warned – they’re not chew-proof.

You may need a tall ladder if you plan to cover all of the fruit on your tree, or you may consider leaving the fruits at the top exposed as a sacrifice.

A spray of capsaicin on forming fruits may help to deter the fuzzy foragers for a short time, but after a heavy rain, it’ll likely wash away. You can continue to reapply if you notice some success in keeping their fidgety whiskers off of your pomegranates.

In conjunction with one of the other aforementioned methods, you can add a plastic decoy to the tree or shrub, such as this faux hawk, available from Walmart.

Decoys such as these can give the squirrels a scare that keeps them away temporarily, but you’ll need to move it every so often to keep them guessing so they don’t get used to its presence.

Ultimately, you may end up standing in your yard banging a pot with a wooden spoon to scare them off. Trust me – we’ve all considered doing this!

Not all pests that you may encounter are the kind with whiskers and fur. Insects can also target your pomegranate trees. Read on to discover the most common types you may encounter.

Aphids

Once again, it’s our old foe, the aphid. You might wonder, how could an insect so small cause enough damage to affect an entire tree?

The answer is twofold: they not only pierce plants to feed on the sap inside in large amounts – much larger than you might imagine – but they also spread disease by carrying pathogens between infected and healthy plants.

Issues such as these might be minor if not for the fact that they tend to breed exponentially throughout the spring and summer, leading to a major infestation of insects that are all constantly feeding.

Aphids can be a nuisance to get rid of as well, often hiding effectively and laying so many eggs that they keep coming back. It can be even more challenging to rid a tree of them when most are out of sight and out of reach.

Learn about combating aphid infestations in our comprehensive guide to aphid control.

Citrus Flat Mites

Among the more difficult pests to spot, you’ll find Brevipalpus lewisi, the citrus flat mite. These pests are also known as false spider mites.

If you’re familiar with spider mites and know how difficult they are to detect prior to spotting their webs or the damage they cause, then you’ll understand how difficult the citrus flat mite can be to spot.

This is an even smaller species, measuring in at just one-tenth of a millimeter long.

The adults, which are amber-colored, prefer warm temperatures in arid climates, and will most commonly infest pomegranates during the warmest months of the year.

Depending upon the seasonal temperatures in your region, you may see them any time between April and September.

Their eggs are nearly imperceptible with the naked eye even though they are red in color. These are laid through the summer months on both fruit and leaves.

Both nymphs and adults feed on plant fluids. They tend to target fruits that have already been damaged, and may cohabitate with thrips and other insects that leave breaches in the surface of the fruit, making access easy.

Damage appears as scabbing or russeting, patches on the surface of the fruit that are rough and brown. Signs of viral or fungal illness may appear when they’re present as well, as they’re known to spread disease they pierce the plant to feed.

When temperatures begin to fall, the mites will prepare for dormancy by colonizing under bark, in deep ridges, and inside the folds of blooms, where they’ll overwinter until spring.

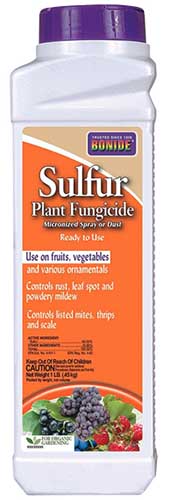

Eradicating citrus flat mites typically involves two steps: an application of neem oil in the dormant months, and an application of sulfur between spring and summer.

Sulfur products can be applied as a powder, or mixed with water and sprayed according to package directions. Allow at least two months between applications of neem oil and sulfur.

Bonide Sulfur Fungicide is available in one-pound bottles or four-pound bags from Arbico Organics.

It works well to combat citrus flat mites, other mite species, and fungal pathogens as well. Be careful not to over-apply it, as this can lead to resistance.

Leaf-Footed Bugs

There are dozens of insects in the family Coreidae, including Leptoglossus phyllopus, the Eastern leaf-footed bug.

These insects bear a strong resemblance to assassin bugs, which are known to be beneficial predatory insects in the garden. However, while they’re similar in form, they differ greatly in function.

Whereas assassin bugs prey on other insects, and can sometimes aid in ridding the garden of annoying pests, leaf-footed bugs are herbivorous and pierce plants with their mouthparts to suck the sap out like aphids do.

Adult leaf-footed bugs are large – sometimes three-quarters of an inch to one inch long. They tend to be dark brown or gray in color, although some display bright colors like yellow and orange as well.

Some have distinctive markings on their backs, like a checkerboard pattern or brightly colored spots.

Their heads are small and pointed, their antennae and legs are long and spindly, and they have violin-shaped bodies. The adults typically have a frill along the ends of their rear legs, the reason for their common moniker, “leaf-footed.”

Adults are fairly slow-moving, but they can fly, so they are capable of infesting plants across the garden at a quick clip. They feed on many types of fruit and vegetables, but particularly enjoy tomatoes, blackberries, and pomegranates.

The adults can lay their brown eggs throughout the year in USDA Hardiness Zones 7 to 11, depositing them underneath leaves and on branches where they will often go unnoticed.

The nymphs, which are typically bright red or orange, then hatch and begin to feed, consuming as much as they can in the six to eight weeks required for them to mature.

Both adults and nymphs can overwinter in protected areas, and since they are typically present in warmer climates, they can be found in the garden year-round. It takes consistent temperatures in the 20°F or lower range to kill them.

Adults also give off a pungent odor when disturbed, deterring predation.

It can be difficult to find evidence of damage on fruits. You’re more likely to see the insects themselves as they tend to congregate together, especially while in nymph form.

You may see dozens of insects gathered to feed, particularly on fruits that have split on the tree where access is easy.

Damage can sometimes be seen when fruits are cut open, as the proboscis of the insect pierces through and leaves a brown mark on the interior.

Arils on the inside of the fruit may be withered where the insects have sucked the juices from them. You may also observe soft sections of rotting on the exterior of the fruit.

Be sure to check for signs of disease, such as heart rot as described below, on the interior of the fruit, as insects that puncture the flesh to feed can easily introduce disease pathogens as well.

Arils that are not damaged are still safe to consume.

While chemical pesticides such as permethrin can be used to combat these insects, the more environmentally-friendly method is to pull on a pair of garden gloves and gather them up to toss into a bucket of soapy water, provided they are within reach.

One or more applications of neem oil can also be sprayed on the plant, according to package instructions, when the insects are in the nymph stage. Be sure to apply it prior to the onset of temperatures over 90°F to avoid smothering the tree.

Creating an environment in your yard that is friendly to birds, frogs, lizards, and snakes can bring those beneficial creatures in to help keep pest numbers down.

Leafroller Caterpillars

The omnivorous leafroller moth (Platynota stultana) deposits eggs in the spring on weeds, tree trunks, and grass near fruit and nut trees, flowering shrubs, and ornamental plants.

The larvae spend the winter tucked into dense plant material, so it’s important to control weeds and remove tall grass that’s growing near your trees.

Eggs are gray-green and nearly flat. They are laid in a shingle-like formation that can appear scaly.

The adult moths are rusty brown in color with an extended snout-like mouth. They’re small – only about half an inch long – so it can be difficult to see them among the foliage of plants and weeds.

When the eggs are laid, it’ll only take about a week for them to hatch. The caterpillars that emerge will then begin to feed, munching on leaves and burrowing into fruits where they may go entirely undetected.

The caterpillars are only about one-quarter of an inch in length, with a bright green color and rusty brown to orange-colored heads.

After they’ve eaten their fill, they’ll pull a leaf against the side of a fruit and form a silky cocoon where they’ll await emergence as adults.

Caterpillars can ruin your fruits by tunneling into them, but the more significant danger is the potential spread of pathogens that cause diseases, such as Alternaria alternata, the fungus that causes heart rot.

Fruits that have been breached by the caterpillars may still be consumed if the arils are firm and healthy upon inspection, but be sure to look for any signs of rotting, as this may indicate disease. Diseased fruits should not be consumed.

It’s best to stop a serious infestation before it can take hold, as it’s nearly impossible to kill larvae that have reached the pupa stage when they’ve cocooned and shielded themselves inside rolled leaves.

A generous application of neem oil can be sprayed on the tree according to package directions in late winter or early spring, and again in late spring or early summer, while fruits are still small and developing.

You can also use pheromone traps to attract adults and disrupt their mating cycle. Pheromone traps, lures, and glue strips are available from Arbico Organics.

Beneficial bacteria can be applied to the tree to destroy larvae as they hatch, such as Bacillus thuringiensis v. kurstaki.

You can find products that contain the bacteria, such as Bonide Thuricide, available in quart- or gallon-size bottles at Arbico Organics.

Mealybugs

You can find mealybug infestations on a vast number of plant species. Much like aphids, they’ll take what they can get and consume as much of it as possible.

Adults are mostly immobile, attached at the mouth to the plants they pierce to feed from. They can lay hundreds of eggs in a short timespan and typically lay in more than one cycle throughout the warmer months of the year.

Their nymphs, known as crawlers, are more mobile and very small – usually no more than one-quarter of an inch in length.

Again, it can be tough to fight an infestation of minute insects on a large fruit tree, but there are several methods that you can put into practice to reduce their numbers and limit the damage they cause.

For complete information on this pest, see our guide to identifying and controlling mealybugs.

Thrips

There are several species of thrips that are known to inhabit pomegranate trees and shrubs, and most are actually beneficial predators of pest insects, such as mites.

But one of these species, Rhipiphorothrips cruentatus, is not beneficial. This species feeds on the sap of pomegranate plants, much like aphids or mealybugs, and leaves evidence of this behind in the form of damage to your plants.

Young fruits that are infested by thrips may exhibit scabs that don’t allow them to grow properly.

The tight, brown scabs cause deformities that may make the fruit less than desirable fruit. A large infestation can cause leaf curling and discoloration, bud drop, and stunted growth.

Fortunately, an infestation is unlikely to lead to the death of a mature tree, but it can still be a nuisance that you’ll want to address to prevent further issues.

For information on managing an infestation of harmful thrips, see our comprehensive guide to identifying and controlling these pests.

Diseases

There are remarkably few diseases that commonly affect pomegranate trees – that’s the good news. The bad news is that these are often difficult or impossible to treat, and they can lead to significant crop loss or even plant death.

It’s best to keep a close eye on your plants for signs of a problem, so you can catch it early.

Botrytis

One of the most common fungal diseases that gardeners and fruit growers encounter is gray mold, caused by Botrytis cinerea.

This fungus spreads through airborne spores that colonize on damp surfaces. The spores can attach to immature fruits and remain dormant inside the calyxes of the flowers until they mature and ripen.

While it’s uncommon for botrytis to colonize on fruits that are still growing, you’ll need to keep an eye out after the harvest.

Fruits are more likely to fall victim to fungal development when they’re washed but not allowed adequate time and airflow to dry thoroughly, or they’re not kept at cool enough temperatures between 32 and 40°F.

Signs of infection are obvious: thick gray mold develops on the surface of the pericarp, frequently overtaking the entire exterior – sometimes within a matter of days – causing rapid decay.

It’s not possible to prevent the spores from coming into contact with your plants, but there are a few measures you can take to deter the formation of gray mold.

Be sure that your plant is pruned to allow air and sunlight to reach the fruits. Plant surfaces that are dry are less likely to harbor the fungus, while dense foliage retains humidity and water more readily than pruned plants with adequate spacing.

Fungicides can technically be applied both pre- and postharvest, but avoid doing so unless you’ve had a serious issue with botrytis on your pomegranate plants before, or other neighboring plants.

Over-application of fungicides can do more harm than good, leading to resistance.

After harvesting the ripe fruits, be absolutely sure to allow them time to dry in an area with good ventilation.

Spread them out on a dry towel or tabletop for a few hours, and direct a fan toward them if you’ve noticed moisture or live in a humid environment.

Unless you’re going to use them immediately, you should move them to cold storage right away after drying. Fruits that are stored at room temperature between 60 and 75°F are more likely to develop mold.

Or better yet, wait to wash your harvest until just before eating, and dispose of any harvested fruit that show signs of spoilage.

Cercospora Fruit Spot

Signs of this fungal infection, caused by Cercospora punicae, include oval-shaped black spots on branches, brown spots on leaves that spread until they form black patches, and leaf discoloration.

This infection is also commonly referred to as black mold, and it can lead to leaf and fruit drop, as well as eventual death of the tree if left untreated.

In most cases, you’ll likely notice obvious signs before it has overtaken the tree, but it can still cause crop loss.

The fungi often overwinter in bark, rotting fruit, or soil, and spores are spread during periods of heavy rainfall coinciding with warm temperatures.

You’ll want to immediately prune away any infected plant material and discard it by burning or placing it in a well-sealed trash bag away from other plants.

Any shears or equipment that come into contact with infected material should be disinfected before they’re stored or used on other plants.

Be sure that drainage is adequate surrounding the tree, as wet soil will continue to harbor and spread the fungal spores, potentially leading to reinfection. Allow the soil to dry out after watering.

Fungicides can be applied, such as BioWorks Cease, available from Arbico Organics – but again, beware of over-application as it can lead to resistance.

Heart Rot

Heart rot, also known as black heart, is another fungal infection you may encounter. It’s caused by Alternaria alternata, a fungus that affects the interior of the fruit while the exterior retains its healthy appearance.

In fact, you aren’t likely to notice any outward symptoms at all as the fungus spreads through the interior of immature fruits that have been affected, rendering them inedible.

By the time you’re planning to harvest, infected fruits might have an unusually light weight, or they may make a hollow sound when tapped upon.

Arils infected with A. alternata will have a mushy texture, and appear brown or black as the fungus breaks down the flesh. This fungus is known to affect pomegranates and other fruit crops throughout the world.

Heart rot often goes undetected because the fungus actually penetrates the forming blossoms as the tree blooms, remaining dormant inside the reproductive area or ovary at the base until the fruit begins to form.

In essence, the infection grows with the fruit.

At present, there is no known cure or treatment for this condition available. Unfortunately, the most you can do is cull the affected fruits and start over.

At harvest time, you can sometimes shake the tree or shrub gently and infected fruits may fall off on their own.

Be sure to disinfect any garden tools that you use to remove or collect the fruits to avoid spreading spores to other plants.

Planning and Vigilance Go a Long Way

Always do your best to give your pomegranate plants a once-over each day. Taking stock of plant health on a regular basis will make it so much easier to prevent serious problems from developing later on.

Now that you know the warning signs for the most common varieties of pest and disease that may affect your pomegranates, you’ll be more prepared to act when you see them.

How do you keep your pomegranate plants healthy? Share your tips with us in the comments section below – and pictures too, if you have them!

If you’re in search of more information about caring for pomegranate plants, take a look at these guides next:

Great info, but we have termites in the area..any tips? Thanks for you info, much appreciated

Hi Incabell, I’m so sorry that I didn’t see your question sooner! I’m guessing that you’ve already spotted signs of infestation in your pomegranate trees, such as mud tubes on the exterior built but subterranean species. But, fortunately, if you’ve spotted those signs early on, you should be able to deal with the infestation pretty easily. The first thing you can do is inject the nest with termicide. Foam is the easiest to use, but if you’re not comfortable doing this yourself, an exterminator can help with application. Next, you or the exterminator can spray a liquid termicide on the… Read more »

Hi, is the pomegranate susceptible to verticilliose? I have this in my soil apparently.

Hi, and thanks for your question!

Verticilliose, or verticillium wilt, is caused by two species of fungi that only infect vegetable crops. If you’ve got a garden growing, you might see signs of wilt there among plants like peppers, tomatoes, and other common garden varieties.

Pomegranate trees are in the clear!

Hi everyone,

Can anyone tell me what is the difference between a pomegranate fruit fly and a carob moth?

The carob moth – aka the date, almond, or locust bean moth – is Ectomyelois ceratoniae. Small white eggs turn pink just before hatching. The larvae are white or light pink with black heads, and about 20 millimeters long. These pupate, and the adult moths that emerge are about 12 millimeters long and gray. Bacillus thuringiensis can be used to kill the larvae, and cold winter weather will slow down their development. I’m not sure that there’s one type of fruit fly in particular commonly known as the pomegranate fruit fly but several species will attack them, including the African… Read more »