The cicada is an insect in the Cicadoidea family of the Hemiptera, or true bug order, that is related to aphids, crickets, grasshoppers, leafhoppers, and stink bugs.

It makes its home in and around woody trees and shrubs, and has the potential to cause great damage.

And while it may not always be easy to spot, the cicada makes its presence in the landscape abundantly clear by producing a droning, rhythmic buzzing sound that starts out soft and gets louder.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

There are over 3,000 species of this true bug worldwide.

The summer ones are often referred to as “annuals,” because they appear in the landscape every year, although as individuals, each takes between two and five years to complete its life cycle.

Because of their various life cycles, their emergence is random and not overwhelming.

However, there are other species that come out in the spring and are called “periodicals.” They only appear every 13 to 17 years, and in the interim years, they are absent from the landscape.

Their emergence is simultaneous, and millions of them come out at once.

Periodicals are native to the Eastern and Midwestern United States. Any given cohort for a particular year and region is called a “brood” with a Roman numeral following, such as “Brood X,” a 2021 phenomenon I am watching for in my area.

In this brief article, we discuss which trees are at greatest risk for cicada damage, and how to avoid it.

What You’ll Learn

Let’s get started.

The Life Cycle of a Cicada

A cicada nymph lives in the ground near tree roots, where it nourishes itself with sap. It does not feed on the roots themselves.

When its genetically pre-wired timeclock says, “Go,” and the soil reaches an ideal temperature of 64°F, the nymph climbs up out of a hole in the ground.

Sometimes, perhaps if the ground is very wet, it may make a “turret,” or tunnel-like exit hole instead.

Once out, it must shed its exoskeleton and transform from a nymph to a winged adult. This process is called “molting.”

After shedding its skin, it is a “teneral” adult, somewhat whitish, and in need of hardening off before preparing to mate.

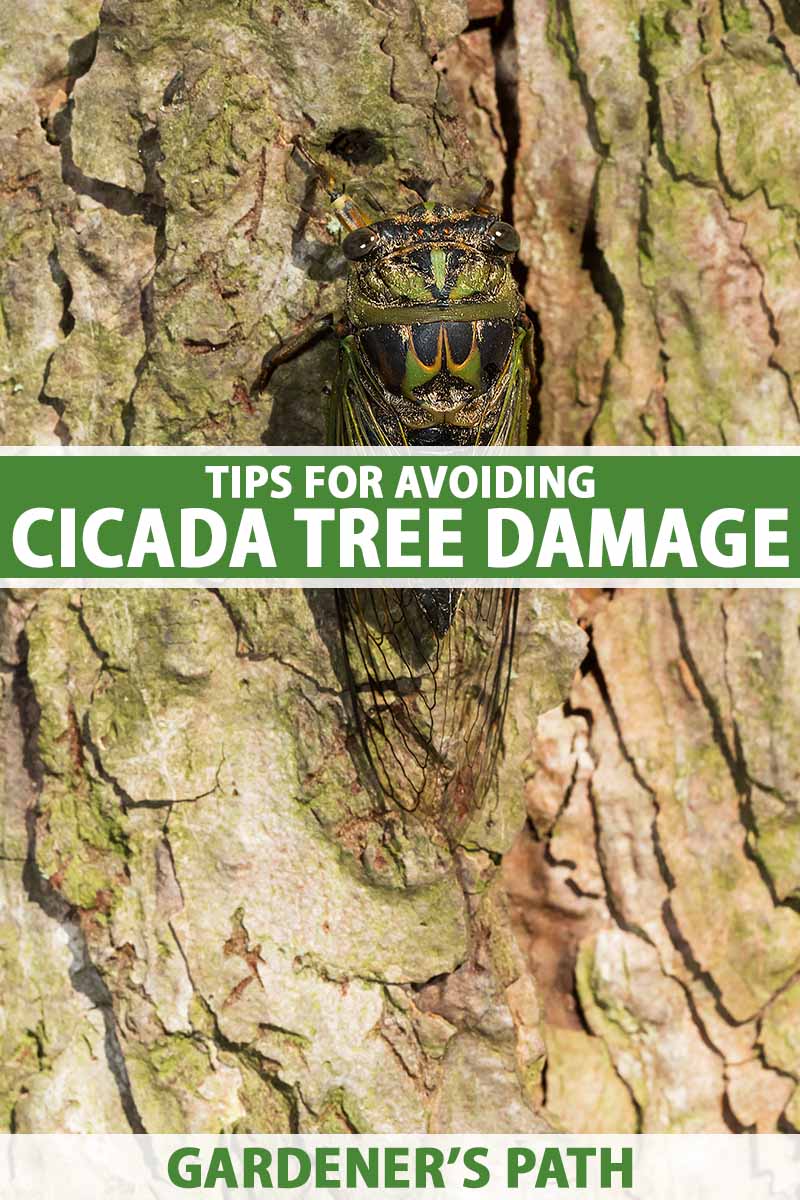

Adult annuals are green and black with black eyes. Their wings are clear with green veins. They can be up to one and three-fourths inches long.

Mature periodicals are black and red with red eyes, and they have clear wings with red veins. They are a little smaller, at up to one and one-fourth inches long.

The next step is for the males to send up their signature buzzing mating call, soon after which the females begin the work of egg-laying.

They locate narrow branches with a narrow diameter that range in size from 3/16 to 7/16 of an inch, and make slits in them with a sharp proboscis-like “ovipositor.” Here they deposit hundreds of eggs.

The tearing of outer bark and inner plant tissue results in damage called “flagging,” that causes branch tips and foliage to turn brown and die.

When the eggs hatch, nymphs fall to the ground and burrow into the soil near the roots, and the adults die.

The life cycle takes place over a span of about two months.

Neither annuals nor periodicals are harmful, so if one flies into you, don’t panic. They do, however, have that sharp ovipositor for wood cutting, so handling them is not advised, as it may result in a puncture wound.

Assessing Vulnerability of Your Trees

A cicada’s preference is for deciduous trees and shrubs, the kind that drop their leaves, and wood with a narrow diameter. And just because it crawled out from beneath one tree doesn’t mean it won’t seek out another to lay its eggs.

It might prefer a very young sapling or immature tree of four years or less, because of the small and tender branches. These trees stand to fare the worst, especially if their trunks are penetrated.

Dwarf trees, especially fruiting varieties that are regularly pruned, may be appealing as well, and may suffer crop losses.

Large, older trees may experience damage to their twiggy branch tips, but as a percentage of the overall area of the tree, it is likely to be minimal and survivable.

Adult bugs may feed on the foliage of trees, but the extent of the damage is usually minimal.

Avoidance Measures

With advance planning, it’s not hard to see trees safely through a spring or summer cicada onslaught.

Here’s how:

Avoid planting trees if a 13- or 17-year periodical event is due in the next four years.

Cover tree canopies with fine, lightweight mesh, such as mosquito netting, and use twine to anchor it snugly around the trunks of trees to prevent climbing nymphs and wingless females from reaching the branches. With care, this product is reusable.

You can also apply a wrap for tree trunks.

This product, available via Amazon, consists of white polypropylene in rolls of 3 by 100 feet. Use it to completely wrap trunks and prevent the upward climb of nymphs. It may be reusable, depending upon wear and tear.

You can also inhibit newborn nymphs from burrowing into the soil by laying landscape fabric around trees out to the “drip line,” or canopy perimeter. Anchor it with bricks or stones.

As a last resort, treat trees with a Pyrethroid insecticide, but use caution, as it is toxic and may kill beneficial insects as well.

Protective coverings for a 13- or 17-year periodical event need to be put in place in April and removed in June, when the reproductive cycle is complete.

And those intended for summer cicada avoidance should be in place in July and removed in September.

In the event of flagging, use sanitized pruners to remove damaged branches to their points of origin. It is unwise to leave decaying plant material in place, as it invites pests and pathogens.

A Choral Warning

In my childhood family, we referred to cicadas as locusts. However, that’s a misnomer, as they are an entirely different species in the Acrididae family of short-horned grasshoppers.

When we heard the droning sound in the morning, we said it meant that the day was “going to be a hot one.” And, being July or August in the Philly suburbs, we were usually right.

When their chorus created a din in the spring, we said, “It’s going to be an early summer,” and maybe it was.

As quaint and hokey as that sounds, what’s worth noting is that these bugs were so loud we couldn’t help but notice them.

And how is this relevant, you ask?

Because regardless of the season or the species, when you hear the males crooning, the females haven’t laid their eggs yet, and there’s still time to protect the most vulnerable trees in your landscape.

What does the brood outlook look like in your area, and have you experienced an onslaught of these insects in the past? How did your plants fare? Share your stories with us in the comments!

And if you found this guide informative and want to learn about other pests and disease that may affect your trees, we suggest the following:

Thanks for this informative article! I came online to see if Brood X was actually damaging my Black locust trees since there are lots of these dried up small branches falling into my driveway. 2004 is when we moved into this house but it was after the cicadas came and went.I’m thinking the trees survived then and should this time.