Ustilaginomycetes

Smut fungi, or Ustilaginomycetes, are parasites that infect plants with teliospores that enter plant tissue, and have the ability to overwinter and return from year to year. They are known as “true” smuts.

There are approximately 1,400 species that blight mainly cereal crops, such as barley, corn, rice, and wheat. Other crops, such as onions, and ornamentals like anemones, carnations, dahlias, and gladiolas, may also be affected.

Plants that contract smut may have stunted growth, discoloration, disfigurement, spotted leaves, and damaged fruit.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

They may develop unsightly balls of spores called galls, or sori. Inside are masses of teliospores. As the galls age, they release clouds of spores that waft through a growing space and land on foliage and soil.

In this article, we discuss black smut fungus, its effects on various plants, and ways to avoid infection in the home garden.

Here’s what’s in store:

What You’ll Learn

Let’s learn about this challenging disease.

Host-Specific Species

There isn’t just one type of black smut fungus. Rather, there are many host-specific species.

Some varieties inflict systemic damage, living in plant tissue and evolving as a plant grows.

Others are localized, damaging only the parts they come in direct contact with.

When an infection is systemic, entire plants are affected, and their seed and debris can further spread disease.

Localized damage, on the other hand, affects specific portions of plants. Some fruits may be unaffected, and seed and debris may not carry the disease.

The fungi cause dark streaks and blisters on plants that develop into galls that contain masses of spores. When the spores are dispersed, they may be carried by a breeze, an insect, or water to species-specific host plants.

Spores can overwinter in soil, plant debris, rootstock, or seeds, just waiting to germinate.

Examples of smuts and the species-specific fungi that cause them include, but are not limited to:

Anemone

Anemone smut, Urocystis anemones, appears as yellow/brown blisters on the foliage and stems that darken to brown/black, and release masses of sooty spores.

This type is systemic, and can winter over in the anemone rhizome, or fleshy root, and cause infection again the following year.

Anther

Anther smut fungus was formerly classified as Ustilago violacea, in the Ustilaginaceae family, and considered a “true” smut.

It is now known as Microbotryum violaceum, and has been reassigned to the Microbotryaceae family, which also contains fungi.

There has been and will continue to be much reclassification with scientific advancement in this area.

This type affects members of the carnation family. It retards growth, makes the foliage grassy-looking, and damages flower buds and blooms. Where there should be pollen-laden anthers, there are sooty spores instead.

This is a systemic disease that invades foliar tissue and germinates there. It affects mostly young vegetation, and is not harbored in soil.

Fungicides containing tebuconazole have proven effective against this disease.

Barley

Loose smut of barley, caused by Ustilago nuda, is a systemic condition that affects entire plants.

This is a systemic disease that invades flowers, contaminates seed, and colonizes grain heads with spore-filled galls.

Seeds are often pre-treated with fungicidal triadimefon to inhibit infection.

Corn

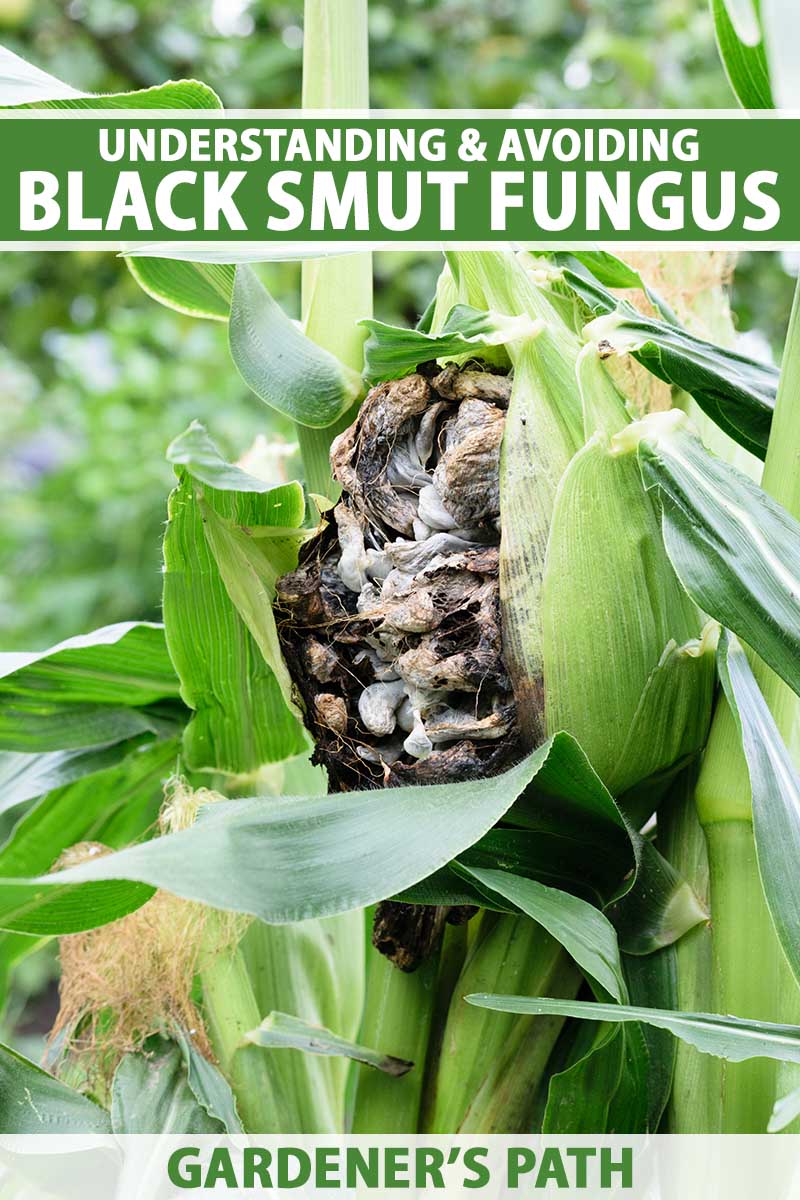

Corn smut, aka common smut, Ustilago maydis, affects sweet corn.

It winters over in soil and foliar debris, and penetrates developing ears and sometimes tassels (cornsilk).

Galls full of mold spores form, giving the kernels a swollen, gray/black appearance.

This kind may attack multiple times during the growing season, and may deform or kill the youngest vegetation.

And while unsightly, the affected ears are not only still edible, but considered a culinary treat in places such as Central Mexico, where these “huitlacoche,” aka maize mushrooms or Mexican truffles, are savored.

Corn smut is considered a localized infection that does not affect the entire plant.

There is no chemical control for this disease. Remove all galls and dispose of them along with all plant debris in the trash to avoid spreading it.

Another fungus known as head smut, Sphacelotheca reiliana, is also soilborne. Unlike corn smut, it is systemic, lurking inside a plant’s cells as it matures, and attacking with galls at the flowering stage.

This type is not a “true” smut of the Ustilaginaceae family, but a member of the Microbotryaceae family of fungi.

Fig

Several species are known commonly as fig smut – Aspergillus carbonarius, A. japonicus, and A. niger. These attack the inside of the fruit, filling it with a mass of teliospores that puff into a black, sooty cloud once dry.

Spores live in the soil and vegetal debris. They can be carried by insects, or they can penetrate maturing fruits directly through cracks.

Aspergillus molds are members of the Trichocomaceae family, and are not true smuts.

There is no available chemical control for this disease. Discard all affected figs and vegetation in the trash to inhibit its spread.

Onion

Onion smut, caused by Urocystis cepulae, U. magica, and U. colchici, affects the first cotyledon, or seed leaf, of onions, as well as chives and shallots.

It can live for 15 or more years in soil. Dark streaks are followed by spore masses, and then the death of most seedlings.

The infection is systemic, and surviving onion plants aren’t likely to enter the reproductive stage and produce onions.

Some farmers drench furrows of onion seeds with a fungicide containing mancozeb at planting time to inhibit this disease, but many gardening experts recommend using seed that has been examined microscopically and certified disease-free instead.

What is most unique about this disease is that once seedlings are past the cotyledon or seed leaf stage, they can be transplanted to soil infected with onion smut with no fear of contracting it.

U. colchici also has other hosts, including the autumn crocus, a flower native to the United Kingdom. The telltale signs are trails of sooty black spores along the foliage.

It occurs so rarely in the UK that it is classified as a protected and endangered species, and the picking of infected flowers is prohibited.

Rice

Rice kernel smut, aka kernel bunt of rice, is caused by Tilletia barclayana. It lives in soil and can float on the water in rice fields. It can also be found inside the seeds themselves.

Mature galls release teliospores that infiltrate rice blossoms, and blacken rice kernels. Infection may be systemic or localized.

Rice kernel smut may respond to fungicidal treatment with a product containing propiconazole.

It must be applied when the rice has a “… two- to four-inch panicle around the mid-boot stage of development,” per Dr. Dustin Harrell, an extension rice specialist from Louisiana.

Once the boot, or bulge in the leaf that contains the rice kernel, splits, it’s too late.

In addition, there is also a false smut of rice, Ustilaginoidea virens, that penetrates rice and causes yellow-orange galls to develop that deepen to blackish green and destroy kernels.

This infection is localized, and is also generally treated with propiconazole.

Turfgrass

There are multiple species that may affect lawns. They are often referred to as leaf smuts and fall mainly into the Urocystis and Ustilago genera.

Symptoms include yellow striping on the blades that turns grayish before releasing spores.

Two types, stripe, Ustilago striiformis, and flag, Urocystis agropyri, affect cool-weather perennial grasses like Kentucky blue, redtop, and timothy.

The term “flag” refers to the last leaf to form before seed sets, or the final stage in the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth.

Fungi specific to turfgrass may live in soil for years before causing systemic infection.

With good cultivation practices, chemical treatments are usually unnecessary. However, fungicides containing propiconazole may be suitable for use.

Wheat

Loose smut of wheat, Ustilago tritici, is seedborne. With the naked eye, there is no way to know that seed is affected.

Infection occurs when spores invade a flower that then sets seed. A silent threat until the seed is sown, this results in stunted growth, and kernels compromised by masses of dark brown spores.

The infection is systemic.

In addition, there is also flag smut of wheat, Urocystis tritici. It differs from loose smut in that it is not systemic, and only affects the developing kernels, as opposed to the entire plant.

And there are two species of stinking smut of wheat, Tilletia tritici and T. laevis, that originate in infected seed and cause stunting, greasy greenish discoloration, and masses of black spores where healthy kernels should be. It gets its name from the fishy odor of the dispersed teliospores.

These types originate in seed and cause systemic infections.

Fungal infections of wheat are often addressed at the seed level. Commercial growers commonly treat seeds with a product called Charter F2, an FDA-registered fungicide product that contains triticonazole and metalaxyl.

A Word on White Smut Fungi

In addition to black smut fungi, there are white smut species of the Entyloma genus that may affect garden ornamentals.

The infection begins in the foliar tissue, causing white, tan, or yellow patches to form on foliage that darken and join, causing tissue to turn black, or necrotic, and die.

Entyloma species are soilborne, and they can winter over and cause repeated localized infections.

Examples are fungi that affect dahlias, E. dahlia, calendulas, E. calendulae, and sunflowers, E. helianthi.

Other ornamentals that are susceptible include alliums, coneflowers, forget-me-nots, and rudbeckia.

However, instead of there being identifiable causative species for each, the offending fungi are currently lumped into the generic classification E. polysporum.

White species are considered manageable, and a one-size-fits-all fungicide that is effective against rusts and mildews is generally the treatment of choice.

Favorable Conditions

With an overview of numerous species and the threats they pose, let’s move on and try to understand what activates them in the first place.

Conditions that stimulate fungal germination and teliospore dispersal include:

Injured Tissue

Flora that is compromised because of damage to roots, stems, foliage, and flowers is more susceptible to opportunistic parasites that reach their hosts via air, insects, and water, and seek a point of entry.

Nitrogen-Rich Environments

A characteristic of parasitic fungi is that they seem to be the most aggressive in places where the soil is especially rich in nitrogen.

This may be due to the use of a fertilizer that has an N-P-K ratio that is heavy on the “N,” instead of being well-balanced.

A nitrogen excess may also be the result of runoff from overfertilized turfgrass.

Overcrowding

When plants are too close together, moisture evaporates more slowly, causing foliage to stay wet for prolonged periods, and the ambient humidity to rise.

Wetness and humidity are conditions that some fungi favor.

Poor Sanitation

Failing to disinfect garden tools after working with diseased flora, as well as the shoes you wore at the time, can contribute to the spread of pathogens.

Similarly, debris like spore-contaminated fruits and foliage that remain on the ground can further support fungal development and overwintering.

Temperature-Moisture Connection

Conditions that are extremely dry may render plants vulnerable to flag smut of wheat, Urocystis agropyri, and stripe smut, Ustilago striiformis, especially when temperatures are cool.

On the other hand, onion smut, Urocystis cepulae, prefers conditions that are wet and cool.

And weather that is very rainy with high humidity and temperatures between 80 and 95°F creates the perfect setting for corn smut, Ustilago maydis.

Tips for Avoidance

Knowing the conditions conducive to fungal disease informs our gardening practices, so we can do our best to avoid contracting it altogether.

Here are some proactive steps to take:

Adjust Planting Times

It’s possible to vary planting times somewhat to avoid conditions fungi favor, like commercial growers strive to do.

For example, as mentioned, corn smut requires temperatures between 80 and 95°F for gall formation. So, at home, you may try sowing early-season varieties that are well underway before summer heats up.

Avoid Nitrogen-Heavy Fertilizers

As mentioned, smuts thrive well with heavy nitrogen, so opt for well-balanced fertilizers, or those with a lower percentage of “N” in the N-P-K mixture.

In addition, don’t fertilize the lawn until autumn, when the temperatures have cooled and the fungi are dormant.

Buy Disease-Resistant Plants and Seeds

Always deal with reputable purveyors.

Quality seed that is pre-treated with fungicide, as well as disease-resistant cultivars raised in greenhouses with minimal pathogens, go a long way toward supporting the health of crops and ornamentals.

However, understand that there may be numerous “races” of pathogens within any given fungal species, so pre-treatment is not foolproof.

Additionally, over time, fungi can develop resistance to specific fungicides, rendering them ineffective.

Don’t Overcrowd

The biggest crop yield or fullest ornamental garden will be pipedreams unless you remember that in addition to sunlight and water, plants need breathing room to inhibit the spread of disease.

Ample airflow is essential, especially to deter fungi that thrive in excess humidity generated by overcrowding.

Remove Weeds and Debris

Vigilant weeding to maintain airflow and keep disease-carrying insects from congregating contributes significantly to garden health.

And removing damaged and/or diseased plants helps to prevent the spread of pathogens.

Dispose of all vegetal debris. Non-infected material can go on the compost heap. Diseased material like stems, leaves, and fruits must go into the trash.

Rotate Growing Areas

In the event of a disease outbreak, don’t sow the affected plant variety in the same place next time. As we have discussed, pathogens can winter over in soil and foliar debris, just waiting for the same host to appear again.

As the fungi are species specific, rotating crops helps to inhibit recurrent infections.

Sanitize Equipment

From pruning shears to gardening shoes, disinfecting equipment after use minimizes the manual transmission of pathogens throughout a growing space.

You can sanitize your equipment by using a 10 percent bleach solution or 70 percent alcohol.

It’s a chore that is well worth the effort.

Water with Care

Always water at the soil level, not over the foliage, to avoid perpetual dampness.

Consider a drip irrigation system to facilitate the process. This is an especially good way to water the lawn.

Take care not to over- or underwater.

Maintain lawn moisture to impede turfgrass fungi that thrive in dry blades.

Where microscopic spores exist in the soil, a splash can wash them up and onto the foliage of a host species.

So, when watering the lawn, avoid dousing ornamentals growing nearby. Their lower leaves are especially susceptible, and as they are shaded by those above, they are likely to become damp breeding grounds.

And lastly, take care not to bump into crops and ornamentals with equipment like garden hoses, as injuring them creates openings for spore penetration.

Prevention Is Best

To sum up, the best way to deal with smut fungus is to avoid it to the best of your ability with disease-resistant seed and plants, an understanding of conditions that favor its development, and appropriate practices to avoid contracting host-specific diseases.

There are many pathogens that may present gardeners with challenges. Symptoms are often difficult to distinguish, especially if there is more than one disease underway.

To handle what you believe to be an outbreak, consult your local agricultural extension service for confirmation and further advice.

And finally, if you have mold allergies, consult with your allergist or GP before dealing with fungus in the garden.

Have you battled smut fungus in your garden? Let us know in the comments section below!

If you found this guide informative, and want to learn more about fungal diseases of plants, we recommend reading the following next: