Claytonia spp.

As a teenager out on a hike on a cloudy March day, I came across a plant that had strange round leaves, each with a stem sticking right through the middle and a tiny white flower at the top. I was out hunting for ghost towns, but I’d found something much more exciting.

I’d heard about the fabled “miner’s lettuce,” a plant that prospectors carried with them into the gold mines during the days of the gold rush in western North America to help them avoid scurvy.

Now, let’s be clear. While we don’t have any clear records to confirm as much, I’d bet my last dollar that these laborers learned about the plant from the native people inhabiting the area.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Native people had been eating the plants for centuries before prospectors started tunneling into the ground.

Anyway, here I was, a teenager looking at those legendary greens, and I was so excited that my companions wondered if I had discovered literal gold. In my mind, it was even better.

The distinctive leaves made it easy to identify my first foraged greens. I munched tentatively on a few leaves, and I immediately had the foraging bug.

I enjoyed them so much, and since I couldn’t always count on finding them in my suburban neighborhood, I figured I’d need to grow my own.

Cut to a few years later and me begging my mom to stop pulling up the seedlings I’d surreptitiously planted among her ornamentals. She insisted they were weeds, but I knew better.

Now that I’m an adult with my own garden, I can and do grow this plant every winter and spring in my garden, and year-round as microgreens on my windowsill.

If you’re looking for an unbiased account of miner’s lettuce, I can’t give you that. I’m unabashedly a fan. But if you want to learn how to grow and care for this delectable green, look no further.

I’ll also help you figure out how to forage them if you’re a budding forager like I was.

Here’s what we’re going to chat about:

What You’ll Learn

The faster we get started, the better, because my mouth is watering just thinking about the leaves.

What Is Miner’s Lettuce?

Claytonia (formerly Montia) species are also known as spring beauties, while the “miner’s lettuce” term is reserved for several species that grow in western North America, a few of which are extremely common and others which you might only rarely stumble across.

These species are all part of the Montiaceae family, but were formerly classified in the purslane family, Portulacaceae. They are closely related to the succulent plants in the Lewisia genus.

C. perfoliata, also known as common miner’s lettuce or winter purslane, is found growing wild across western North America.

The subspecies perfoliata is found in the Pacific Northwest and northern California, while the subspecies intermontana grows wild in the interior regions as far west as the Rockies. Subspecies mexicana hails from southern California and Mexico and as far east as Arizona.

This species has even hopped over the Rocky Mountains and grows in areas where it isn’t native, including Arkansas.

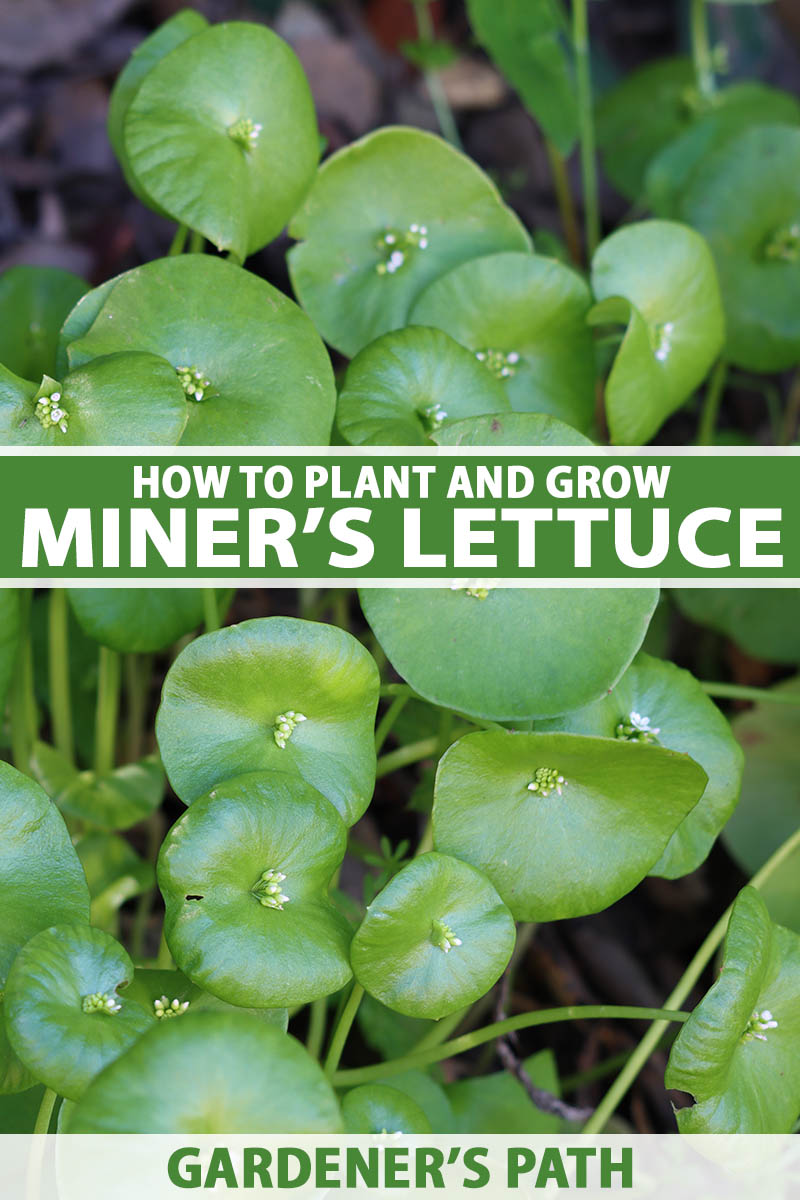

Perhaps the most notable characteristic of these plants are the leaves. It looks like the flower stalk has punched through the center of the leaf, which is actually comprised of two leaves that have fused together. This type of growth is known as being perfoliate, hence the species name.

The leaves can be orbicular (round) or rhombic (square), and they grow at the end of long petioles.

The young leaves are ovate, and transition to cordate (heart-shaped), before taking on their final form.

Tiny white or pale pink flowers emerge in late spring or early summer. The plants can reach up to a foot tall in ideal conditions but will stay shorter if planted in heavy soil or shade.

Identifying the mature miner’s lettuce is much easier than the younger plants, so stick to foraging the mature plants if you’re new to the game. Look for those saucer-like leaves with the flower stem growing out of the middle.

The only lookalike is dollar weed, aka water pennywort (Hydrocotyle spp.), but the flowers grow on separate stalks, not through the middle of the leaves.

Siberian miner’s lettuce (C. sibirica) is found on islands in the Bering Strait and from Alaska to the Santa Cruz mountains of California.

The flowers have five petals that are white or pink with dark pink stripes. They appear on the plant as early as February, depending on the area, and can continue until the fall.

The glossy, veined leaves are lanceolate when young, which means they’re long and narrow with a slight flare in the middle. Once they mature, they become deltate or triangular, with two leaves per stem. The leaves of this species do not fuse as they do in the case of C. perfoliata.

This one is a little harder to identify because it has a few lookalikes, the most common being red campion (Silene dioica) when it’s young and not in bloom.

C. sibirica is more common in the wild in its native range. But both species are found in most moist, somewhat shady areas. It doesn’t matter if it’s a woodland, a field, or disturbed sites, if it’s moist, miner’s lettuce is moving in.

I grab it from the abandoned roadside and next to riverbeds near my house.

Bees, butterflies, moths, and other pollinators love these plants, and the birds will eat the leaves and seeds, as will small mammals.

In hot, dry weather, the plant dries up and goes dormant until the winter.

A few other species are sometimes cultivated or foraged, but they aren’t nearly as common as the species described above. They’re all edible to some degree, though the two mentioned above are the tastiest.

In western North America, C. lanceolata has fleshy, strappy leaves and looks more like a desert succulent than a herbaceous green.

Another western native, C. parviflora, known by the outdated moniker of Indian lettuce, looks nearly identical to C. perfoliata, but it grows in drier, warmer areas.

C. rubra, or erubescent miner’s lettuce, looks similar to C. perfoliata but has red foliage.

Marsh claytonia, C. palustris, looks nearly identical to C. sibirica.

On the eastern side of the Rockies, eastern spring beauty, C. virginica, grows in the eastern half of North America and has similar flowers to Siberian miner’s lettuce, but the leaves are long and strappy.

Also growing in eastern North America, C. caroliniana, or Carolina springbeauty or spring beauty, looks extremely similar to C. sibirica and grows in similar conditions. The leaves are just as flavorful, with the added bonus that you can eat the tuberous root as you would a potato.

While we’re on the topic, all parts of the Claytonia species mentioned here are edible, with some species, like C. caroliniana and C. tuberosa having large, tuberous roots that are quite tasty. These plants are full of vitamin C, protein, iron, and beta-carotene.

The name Claytonia pays homage to botanist John Clayton, who collected many plant specimens in the 1700s.

Cultivation and History

The story of plant migration in North America has a typical pattern.

European settlers brought plants to North America that they’d collected at home or from countries they’d explored, such as China or India, and those plants gradually naturalized in their new location. In some cases, these species became a downright menace.

But only a few North American native species managed to prove special enough to make the trip in the opposite direction, from North America to Europe, to become a common wild and garden plant rather than just a specimen in a museum. Miner’s lettuce is one of those plants.

Miner’s lettuce was brought by European explorers back to Europe and has since been introduced to other areas like Argentina, Cuba, Australia, and New Zealand, where it has naturalized.

Scottish naturalist Archibald Menzies usually gets the credit for bringing the plant to the UK during the 1700s, and that’s probably a good guess, since he was well-known for collecting all kinds of species.

It’s likely that he brought some miner’s lettuce on his ships to keep his crew healthy. He eventually presented some plants to the Royal Botanical Garden at Kew in 1794.

From there, home growers became interested in the plant and began growing it in their home gardens.

It became such a vital crop that it’s credited with keeping soldiers healthy in the UK during WWII.

Back in its native home, people such as the Kawaiisu, Diegueno, Costanoan, and Mendocino ate the plants, and many tribes used C. perfoliata as an appetite restorer, eye medicine, and for arthritic pain. C. sibirica was used as a hair wash, eye treatment, and for relieving sore throats.

Miner’s Lettuce Propagation

The vast majority of us will grow miner’s lettuce from seed, but if you know where a patch is growing, you can divide some of the plants and put them in your garden, so long as it’s legal to do so.

Let’s start with the most common method.

From Seed

When sourcing seeds, look for reputable sellers. Some areas have been deprived of this lovely ephemeral because of overharvesting by commercial seed sellers.

Similarly, if you are foraging, make sure you leave enough behind so the plant can replenish itself.

Miner’s lettuce seeds germinate best in cool conditions when the soil is between 50 and 65°F. You can direct sow outdoors whenever the soil is between these temperatures, or start seeds indoors.

The seeds will germinate in cooler soil, but they will take longer to sprout or remain dormant until temperatures increase.

Where I live, the plants emerge from the ground in the winter when the soil is around 40°F or a bit below – so as long as the soil can be worked and it isn’t too soggy, you should be fine.

Work some well-rotted compost into the soil if your soil is somewhat sandy or clay.

Sow the seeds half an inch deep and either scatter them or space them about an inch apart. A shallow seed tray works well indoors or you can sow directly outdoors.

As the seeds germinate, which happens rapidly – usually within a week in ideal temperatures – thin the seedlings to about four inches apart once they’re about an inch tall. Eat the baby greens, don’t waste them.

Give the developing seedlings about six hours of light per day, whether that’s sunlight or indoors with supplemental light.

Keep sowing every few weeks for a successive harvest.

If you started the plants indoors, wait until they have developed at least two true leaves and then harden them off for a week before putting them in the ground.

If you’ve never hardened plants off before, the process is simple.

Take the seedlings to the location where you’re going to transplant them and leave them there for an hour. Bring them back inside. The next day, add an hour. Keep doing this each day for a week.

By Division

If you have access to a clump of live miner’s lettuce plants, division is an easy process and a reliable way to propagate new plants.

Remember, know your local laws when foraging, and always ask permission of property owners before taking anything.

To divide, take a trowel and dig out a section of the plant.

It doesn’t matter how large of a section you take since each stem is an individual plant, but try to get at least a few stems to ensure enough survive the move to start a new clump.

You don’t need a wide margin, but dig down deep enough to get all the roots.

Keep the soil around the roots moist as you move the division to its new area, if necessary.

Dig a hole in the ground that is the same size as the root ball you dug up, and place the plant in the hole, and backfill with soil. Water well.

Transplanting

I’ve never seen miner’s lettuce nursery starts for sale, but that doesn’t mean that there aren’t a few sellers out there offering them up.

If you find some, or if you want to transplant your own seedlings that you started inside, the process is the same.

Work some well-rotted compost into the ground where you intend to plant unless your soil is already loamy.

Dig a hole about the same size as the growing container. Gently remove the clumps from their existing container and lower them into the hole you made.

Firm the soil up around the clump and water well. If the soil settles, add a bit more.

How to Grow Miner’s Lettuce

Before you decide where to put miner’s lettuce, think about how much you really want to grow.

In the right conditions, it reproduces rapidly and can spread far and wide.

You might think you’re providing it with just a little partially shady corner in your garden, but in a few years, you’ll be digging it out of your driveway and next to the front lawn.

In addition, when the birds and ants snatch the seeds and carry them, they help spread this plant around the garden.

For most people, it’s not a problem. It’s a pretty plant, and it isn’t invasive, it’s just opportunistic.

I personally harvest all of mine before it sets seed in the late spring, and I’ve never had it escape.

If you’re really worried about it spreading, plant in an area with some boundaries, like a raised bed or a container, and harvest before it goes to seed.

Keep in mind that if you do that, miner’s lettuce might not come back next year if it’s too warm or dry for too long, and you’ll have to sow new seed.

So long as the weather is cool, miner’s lettuce will grow in anything from full shade to full sun in Zones 6 to 9. Temperatures below freezing won’t bother them, but anything above 70°F is the danger zone.

Those in shadier areas will produce fewer blooms and will be a bit leggier, but since each stalk only grows one leaf (or set of leaves), it doesn’t matter how long the petiole is. There will just be more for the munching.

Although miner’s lettuce is adaptable, it prefers humus-rich soil.

The plants are extremely cold-hardy and they’re a favorite for gardeners who want to grow winter crops in a cold frame or even out in the garden.

They will overwinter in most parts of North America, though they might be buried under snow for part of the time.

Just as miner’s lettuce will adapt to a variety of different sun exposures and soil types, it’s also adaptable when it comes to moisture.

When the plants are young, the soil must be kept consistently moist. As they mature, a little bit of drought won’t hurt, but try to keep the soil evenly moist.

Don’t bother fertilizing this plant, though working in a good bit of well-rotted compost when you plant won’t go amiss.

Growing Tips

- Work in well-rotted compost at planting time.

- Grow miner’s lettuce full sun to full shade.

- Keep the soil consistently moist.

Maintenance

As the days get hot, the miner’s lettuce will go to seed and then will die back to the ground. If you want a new patch next year, let the plants go to seed and drop to the ground naturally.

But if your goal is to prevent miner’s lettuce from going to seed, pluck the flowers as soon as the temperatures start climbing over 70°F and the flowers close.

Where to Buy Miner’s Lettuce

Remember, you want to source seeds from reliable and ethical growers so as not to harm indigenous populations of miner’s lettuce.

You should also carefully examine the images when buying because C. sibirica and C. perfoliata are often mislabeled.

A quick internet search shows plants that are clearly labeled as the other species.

They grow in similar conditions and taste similar, though some people prefer the more succulent crunch of C. perfoliata.

Miner’s Lettuce, C. perfoliata

C. perfoliata is much more common in the commercial market.

High Mowing Organic Seeds is a reliable seller that carries C. perfoliata seeds in a variety of packet sizes and in bulk.

Managing Pests and Disease

Don’t you just love a plant that has hardly any problems with pests and disease? Claytonia is pretty tough.

Slugs and snails and herbivores like rabbits and deer are the most common pests to watch for.

Unless you have free-ranging chickens. Don’t even let them hear you say the words miner’s lettuce.

Herbivores

These plants are tasty, and we certainly can’t expect herbivores to disagree.

Deer

Deer will graze on the miner’s lettuce leaves, but unless they really go to town, it’s not a big deal.

The plant grows right back pretty quickly. Still, if you’d rather not share, fencing or netting is going to be your friend.

Visit our guide for some tips on excluding deer from your garden.

Rabbits

I have an adorable little rabbit living in my old greenhouse, and she sticks around my urban lot, no doubt, because of all the tasty treats I have in my garden.

She seems to love the miner’s lettuce, in particular. I don’t mind sharing, because I plant a pretty good-sized patch every winter, and there’s more than enough to go around.

But if you want to keep the goods for yourself, plant in a container and keep the container close to your home. Or use netting to keep our bouncy friends out.

We have more tips about how to control rabbits in our guide.

Slugs and Snails

Most of us have dealt with slugs and snails at some point. If the leaves are missing entirely, leaving a bare petiole behind, it’s often the work of mollusks.

They’ll also chew ragged holes in the foliage. I use pellets to control them, but we have lots of other useful techniques for snail control in our guide.

Insects

Insects aren’t much of a problem. Even if they do visit, the damage they do is usually minimal. The most common ones to watch out for are:

Aphids

Aphids are sap-sucking insects in the superfamily Aphidoidea.

They are pretty common in the garden and feed on most plants. They aren’t a big deal on miner’s lettuce, causing a little yellowing on the leaves, but the real problem is that they spread turnip yellows virus (TuYV) to the plant.

Once they feed on the plant, they’ve already spread the disease, so prevention is key. Read our guide to learn how to control aphids.

Purslane Sawfly

The larvae of purslane sawflies (Schizocerella pilicornis) will eat the seeds of miner’s lettuce, denying you a crop the following year if you rely on self-sowing.

It’s hard to tell they’re around unless you see the quarter-inch-long, green larvae that resemble caterpillars.

If they’re present, spray your plants with neem oil or insecticidal soap.

If you need to pick up a bottle, head to Arbico Organics, which carries Monterey brand insecticidal soap in 32-ounce ready-to-use spray bottles.

Disease

The only disease that harms miner’s lettuce, either cultivated or wild, is turnip yellows virus.

This disease is spread by aphids and causes the leaves to turn yellow between the veins, reddish spots, and distorted growth.

There is no cure, so if you see these symptoms, you’ll need to pull the plant and dispose of it.

It won’t hurt you to eat it, but the leaves won’t taste as good and it can spread to many species, including turnips and purslane.

Harvesting Miner’s Lettuce

Miner’s lettuce leaves can be harvested as soon as they’re large enough for your tastes.

When fully mature, I’ve seen individual leaves that can reach up to three inches in diameter, but they’re usually half that size.

Siberian miner’s lettuce tastes better when it’s young, while common miner’s lettuce is excellent at any stage.

Harvest by cutting the petiole off near the surface of the soil. You can eat both the petiole and the leaf, they taste the same and the petiole is incredibly tender.

The flavor is similar to spinach but a bit earthier, like a hint of beets, and with a succulent crunch.

Claytonia should be eaten right away after you harvest. It doesn’t store well at all, though you might get a few days if you put it in a plastic bag in the produce drawer of your refrigerator.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

The most obvious way to use your freshly harvested miner’s lettuce is by tossing it into a salad or using the leaves to dress a sandwich. But we can be more creative than that!

The leaves hold up well to brief cooking, so you can toss them at the last minute into stir-fries, risotto, or to top couscous or quinoa.

You can whip them up into a pesto. I like to chop them and toss them onto pasta or soup. You can use the leaves to make soup, too.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Annual or perennial forb | Water Needs: | Moderate |

| Native to: | North America | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 6-9 | Tolerance: | Freezing temperatures, some drought |

| Season: | Winter, spring | Soil Type: | Loamy, rich |

| Exposure: | Full sun to full shade | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.5 |

| Time to Maturity: | 40 days | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | 1/2 inch (seed) | Companion Planting: | Brassicas, lettuce, pansy, viola |

| Spacing: | 4 inches | Avoid Planting With: | Nightshades |

| Height: | 12 inches | Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Spread: | 12 inches | Family: | Montiaceae |

| Growth Rate: | Fast | Genus: | Claytonia |

| Common Pests and Disease: | Aphids, deer, purslane sawfly, rabbits, slugs and snails; turnip yellows | Species: | Caroliniana, lanceolata, palustris, parviflora, perfoliata, rubra, siberica, tuberosa, virginica |

Worth Its Weight In Gold

There aren’t many plants that can provide nutrition throughout the coldest months.

There also aren’t a ton of plants you can forage that taste delicious as-is, without any cooking, chopping, or dressing.

Maybe you can see why I was more excited to encounter this plant than any hard-to-reach ghost town.

I understand if you aren’t quite as excited as I was, but how do you intend to enjoy this delectable delight? Is it destined for a bright pesto or a scrumptious salad? Let us know how you like to use miner’s lettuce in the comments section below.

And if you’re looking for a few other leafy greens to join your miner’s lettuce, read these guides next:

Growing Miner’s Lettuce in your garden or foraging for it in the wild connects us to a rich heritage of sustainability and resourcefulness. It’s a reminder that nature provides us with a bounty of nourishing foods, waiting to be discovered and enjoyed.

Thanks for reading, Lucy!