Vigorous, varied and very, very tough, there’s a yucca for every occasion. These rough and ready succulents can be tall, leggy, and tree-like, or short, squat, and tidily compact.

Often overlooked in the horticultural trade, they’re great natives for dry soils that are difficult to grow in.

Hailing from the Americas, these spiky members of the Asparagaceae family inhabit a wide range of places, from the low and broiling desert to high montane scree fields.

Although a few species prefer humid environments, the majority thrive in arid conditions in freely draining, sandy soils.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

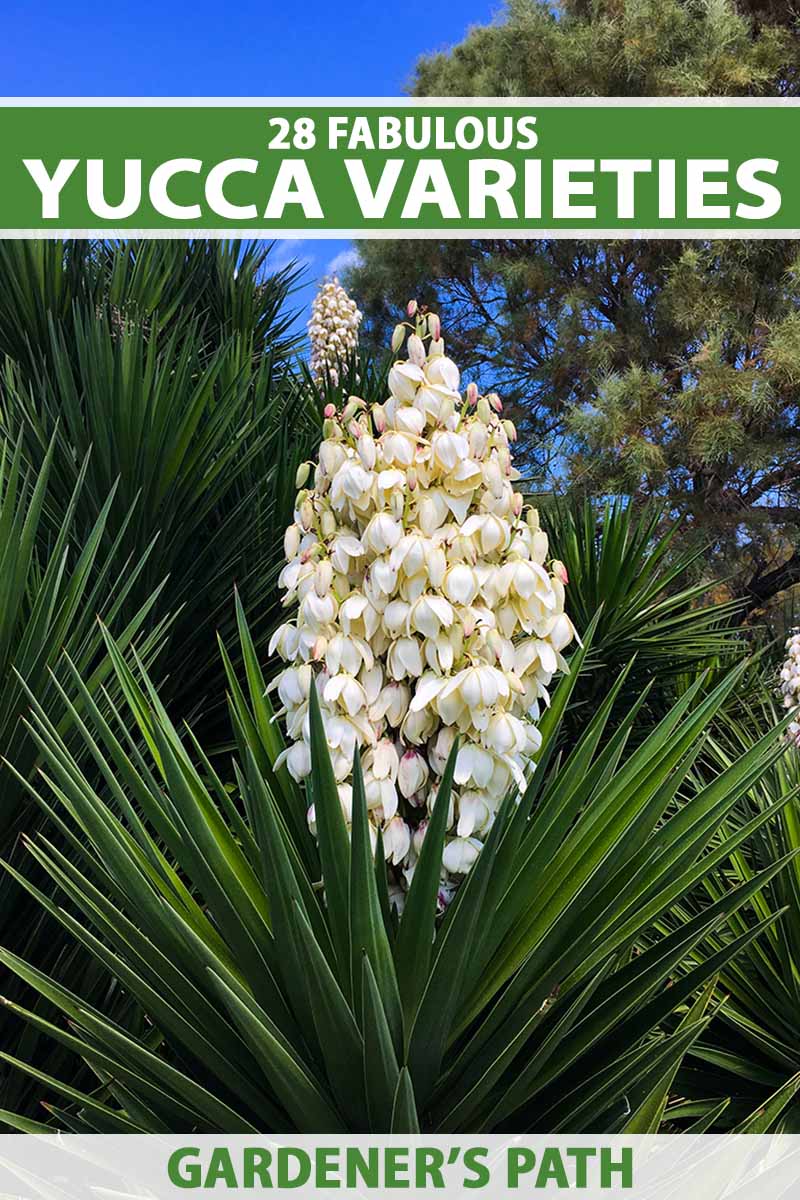

Yuccas’ whorls of long, sword-like leaves and tall panicles of creamy bell-shaped flowers unite the genus and are common across all species.

Interestingly, the flowers rely on moths for pollination. The yucca moth lays its eggs inside the flowers, transferring pollen from one plant to another as it does its work.

Hugely useful, yuccas have been utilized in a myriad of ways across their range.

In some areas, the sharp leaves of these plants were used for piercing and hanging meat. Certain members of the genus were widely valued by native people for their use as a natural soap.

This same soapy quality made a decoction of the plant’s leaves a favorite of native peoples for treating poison ivy, burns, and other skin ailments.

Most yuccas also have edible, sweet-smelling flowers.

The key to growing yucca starts with wise site selection. A happy homemaker on sunny, nutrient-poor, freely-draining soils, yucca wants to grow where many plants don’t.

Beyond that, there’s a smorgasbord of options, so long as you’re within your chosen species’ range of USDA Hardiness Zones.

For further instructions on raising your own yucca at home, read our guide.

Interested in adding this stalwart to your beds? Or identifying some of the best and most beautiful varieties out in the wild?

Read on for a roundup of 28 of the best species for plant lovers within this large, remarkable genus of long-lived plants.

28 Fabulous Yucca Varieties

1. Adam’s Needle

Native to the southeastern United States, Adam’s needle (Yucca filamentosa) is frequently found outside of its range due to its popularity as a hardy ornamental.

Growing up to three feet tall and almost as wide, this tough succulent produces tall spikes full of pale flowers at the beginning of summer, or in late spring.

In its native range, the naturally occurring toxins in this species’ roots were used by the Cherokee to stun fish.

Thriving in freely draining, gravelly substrate, Adam’s needle will grow in a garden bed but is best suited to spots where it won’t stand in moist soils for too long.

When happy, clusters of this yucca will pop up, borne from long, underground rhizomes.

Adam’s needle is hardy in USDA Zones 4 to 10.

You can find plants available in #2 and #3 containers at Nature Hills Nursery.

2. Aloe

This gorgeous native of the Gulf Coast and coastal plains loves sandy soils so much you can even plant it on beach dunes.

Capable of growing to 15 feet tall, aloe yucca (Y. aloifolia) boasts huge clusters of creamy white flowers suspended on long stalks in early summer.

Established aloe yucca produces lateral buds near the base of the plant. These side shoots grow to create a tall, thicket-like copse of trunks.

Evergreen, like the rest of its fellow yuccas, Y. aloifolia makes a great hedge or barrier plant. Plant in full sun for the fastest growth and happiest plants.

Relatively slow growing, but even more so in less than ideal conditions, this species is hardy in USDA Zones 6 to 11.

‘Magenta Magic’ is a dwarf cultivar that sports purple leaves and grows to a mature height of two to three feet tall.

You can find ‘Magenta Magic’ plants in four-inch pots available from Hirt’s Gardens via Walmart.

3. Arkansas

Naturally occurring, as the name suggests, in and around the state of Arkansas as well as Missouri and Texas, Y. arkansana loves freely draining, gritty soils as much as the next yucca.

In fact, mature Y. arkansana plants have taproots several feet in length so they may live long and prosper in the most arid of conditions.

The tough, leathery leaves of this species are about two feet long, gray-green in coloration and sharp tipped.

The plant spreads via lateral, underground stems known as rhizomes, forming colonies. The spindly rosettes can grow to two feet in height, blossoming in late spring.

Arkansas yucca is hardy in USDA Zones 6 to 9.

4. Banana

So named for the green fruits which look vaguely like miniature bananas, Y. baccata is great for soapmaking.

The stiff, spiky leaves were also used by native peoples to make rope and baskets.

The fruit is slightly sweet, and borne on a tall stalk. Growing three feet tall and up to four feet wide, banana yucca is hardy in USDA Zones 4 to 9.

Although this species prefers poor, sandy soils, it will tolerate most types of freely draining soil.

5. Beaked

Beaked yucca (Y. rostrata) is beloved by horticulturalists in the drier, hotter parts of the United States, where it happily tolerates drought and intense sunlight.

Growing a tall trunk up to 12 feet in height, Y. rostrata has long, narrow, relatively soft leaves up to two feet in length.

This species produces a fountain of flowers from the center of its rosette come spring.

Occasionally called “Big Bend yucca,” this moniker is a nod to the species’ native range in Texas.

You can find Y. rostrata available in one-gallon pots from Walmart.

6. Beargrass

Commonly found in the sandy soils of the southeastern United States, beargrass yucca (Y. flaccida) is surprisingly tolerant of cold weather and can even withstand a little frost.

This species is hardy in USDA Zones 3 to 9.

Not to be confused with Y. glauca, another species commonly called “beargrass,” Y. flaccida grows up to three feet tall and almost five feet wide under ideal conditions.

Sporting the same tall flowering spikes as the rest of the members of this genus, beargrass is a sensible choice for tricky, nutrient-poor soils in dry environments.

This species does not do well with a lot of rainfall or humidity.

7. Blue

One look at blue yucca (Y. rigida) and it’s easy to see the species’ resemblance to the closely related and equally spiky members of the Agave subfamily.

Growing up to 12 feet in height and about four feet wide, this succulent comes from the deserts of north central Mexico.

Small for a tree but still surly, Y. rigida bristles with erect, blue-gray, sharp-tipped, and slender leaves.

As the species ages, dead leaves lie down on its trunk forming a thick, textured skirt. In late spring, a tall, broad, flowering spike erupts from the middle of its leaves.

Hardy in Zones 7 to 11, the distinctly blue-gray leaves of this handsome succulent will add texture and structure to the garden if you can provide it with the dry, rocky, freely-draining substrate it needs to thrive.

8. Buckley’s

Buckley’s yucca (Y. constricta) makes its home among the dry hills of Texas.

Another clump-forming variety, this species also eventually grows a short woody trunk to support its rosettes of long, narrow, blue-green leaves.

Y. constricta sometimes inhabits dry woodlands and is tolerant of partly shady conditions.

Growing up to five feet tall, this spring-bloomer produces dense clusters of creamy bell-shaped flowers, beloved by hummingbirds and of course, yucca moths.

Preferring freely draining soils, this species will tolerate clay, loam, and sandy substrates, as long as rainfall is moderate. It prefers slightly alkaline soils and can be found growing on limestone outcrops in the wild.

Buckley’s yucca is hardy in Zones 8 to 11.

9. Cape Region

Currently listed on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature or IUCN’s “red list,” Y. capensis is extremely vulnerable due to its reduced natural range, and habitat destruction. Its native range covers Baja California Sur, Mexico.

Popular as an ornamental, the foliage has also historically been cut and used as forage for cattle.

Cape Region yucca grows up to 15 feet in height, occasionally branching out at the base, and forms large, dense panicles of flowers.

Requiring dry soils and very little water, this species is hardy in USDA Zones 9 to 11.

10. Carrii

A newly discovered species of yucca, this newest member of the genus doesn’t yet have a commonly accepted name.

Discovered along the gulf of Texas, Y. carrii forms colonies of several plants in small clusters.

Interestingly, this new species grows next to brackish or salt water, making it one of the most moisture-tolerant species known.

There’s a whole world of diversity still undiscovered out there, and the yuccas are no exception!

11. Coahuila

Also known as Coahuila soapwort, this species (Y. coahuilensis) touts high levels of the sudsy toxins known as saponins. When its roots are mashed it makes a fantastic, soapy lather.

Listed as “vulnerable” by the IUCN, Y. coahuilensis has a relatively limited native range, occurring in the grasslands of Texas and northern Coahuila, Mexico.

With a flowering spike up to eight feet tall, Coahuila soapwort sports the same rosette of sword-shaped, sharp leaves as many of its relatives.

Lover of dry, nutrient poor soils, this species thrives on minimal rainfall and is hardy in USDA Zones 8 to 10.

12. Creeping Dwarf

Classified as endangered by the IUCN, this short-statured species is exceedingly rare. Still, if you’re up for a challenge, you can find commercially grown seeds online.

Hailing from a small area of Mexico deep in the Chihuahuan Desert, creeping dwarf yucca (Y. endlichiana) stands only three feet tall, with its flowering spike tucked safely into long and spiky foliage.

Blue-green in coloration, Y. endlichiana prefers sandy, rocky soils and is hardy in USDA Zones 8 to 11.

Looking reminiscent of a Sarlaac monster (Star Wars, anyone?) this species is sure to be a unique addition to the garden.

13. Dwarf

Littlest of the bunch, dwarf yucca (Y. harrimanae) grows no larger than one foot tall by one foot wide.

This tough succulent is no less hardy than its larger counterparts, however, and is a good choice for container gardening, or smaller rock gardens.

Hardy in Zones 5 to 9, Y. harrimanae comes equipped with very sharp spines at the ends of its leaves and has dense filaments, or wiry hairs, on its leaf margins.

Fortunately, this yucca-in-miniature still produces the same prolific display of white flowers in spring.

For best results, plant Y. harrimanae in nutrient poor, sandy soils.

14. Giant Spanish Dagger

Endemic to Texas and northern Mexico, this desert dweller is widely cultivated in arid places across the west.

Growing up to 20 feet in height, giant Spanish dagger (Y. carnerosana) is hardy in USDA Zones 8 to 11, requiring maximal sunlight and heat, and minimal rainfall.

This species’ flowering spike emerges right at the top of its rosette, giving it a comical hat of creamy white blossoms perched atop a bulky trunk.

Exceptionally durable and forgiving, this unique succulent is actually quite easy to grow.

15. Giant White

Hardy in USDA Zones 5 to 10, giant white (Y. faxoniana) is another trunk-forming, striking standout within the genus.

Although it closely resembles beaked yucca, its leaves are a little longer, growing up to four feet, and a little wider.

It has the same habit of making wonderful, spherical rosettes, like a bristling pin cushion.

This species prefers the same general conditions as the rest of its kin and thrives in sandy, freely draining soils in full sun.

Like many of the other tree-like types, the spent leaves of Y. faxoniana form a beautiful shaggy skirt up and down the trunk.

16. Joshua Tree

Icon of the Mojave Desert and the American Southwest, Joshua tree (Y. brevifolia) is the largest of all yucca species.

Growing up to 30 feet in height, the Joshua tree is the darling of the national park named in its honor.

Once this tall succulent reaches about 10 feet in height it spreads out, making a crown of vegetation with pom-pom-like rosettes adorning each branch.

Y. brevifolia needs the same nutrient poor, sandy, freely-draining soils present in its native desert home in order to thrive.

It can be grown in rock gardens or xeriscapes but it’s important to make sure specimens or seed for sale were not pilfered from the wild.

Like other yuccas, Joshua tree is susceptible to root rot in humid climates, or places with high rainfall. This species can tolerate low nighttime temperatures, however, and is hardy in USDA Zones 6 to 8.

Read our guide for more info on growing and caring for Joshua trees.

17. Mojave

Mojave yucca (Y. schidigera) is so named as the bulk of this succulent’s population occurs in, you guessed it, the Mojave Desert.

Long-lived and slow growing, this species can reach heights of 20 feet, producing new trunks as it ages. Some Mojave yuccas have been estimated to be 200 years old!

Like many species in the genus Y. schidigera often produces rhizomatous sprouts, creating clusters, or colonies, of new plants.

This species favors hot and dry climates. The hotter, the better! In fact, Y. schidigera is considered fire tolerant and resprouts following lower intensity burns.

This species is hardy in USDA Zones 9 and 10 but does not tolerate ample rainfall or humidity.

18. Narrowleaf

Native to the rocky hills and pinyon forests of the Colorado Plateau, narrowleaf yucca thrives in rocky, freely-draining soils, with lots of sunshine.

Hardy in Zones 6 to 9, Y. angustissima grows approximately 18 inches tall and about two feet wide. Although it is shorter statured, the flowering spike of this species towers above its diminutive rosette at a whopping six to seven feet tall.

Clusters of Y. angustissima rosettes typically form large colonies thanks to plentiful rhizomes beneath the ground.

19. Navajo

This smaller-sized yucca (Y. baileyi) is so named due to its abundance on the tribal lands of the Navajo (Dine) people.

Pounded down to make soap and shredded for its useful fibers, this species has long been culturally significant to the Navajo.

Capable of forming quite dense, compact colonies, Navajo yucca only grows to approximately 18 inches in height, and about as wide. It is hardy in USDA Zones 8 to 11.

Wild populations of Y. baileyi are reportedly stable. Growing this plant at home requires emulating the conditions it receives in its natural habitat.

This species likes freely-draining sandy soils, full sun, and minimal rainfall.

20. Our Lord’s Candle

A truly striking representative of the genus, our Lord’s candle (Y. whipplei) is brilliant and statuesque when its six- to 10-foot-tall flowering spike is on full display.

The native people inhabiting the plant’s range across southern California and Baja California in Mexico used this species to make soap and baskets. The stems can be roasted and eaten, too.

Although our Lord’s candle is utilized in horticulture, it is purportedly difficult to grow outside of its native region, likely due to its extreme sensitivity to overwatering.

This species is hardy in USDA Zones 7 to 9.

21. Pale Leaf

This Texas native grows to two feet high and almost three feet wide.

As its common name suggests, its narrow, slender leaves are paler than those of most other yuccas, and come in a shade of grayish-green.

Hardy in Zones 6 to 10, pale leaf yucca (Y. pallida) prefers sandy, freely draining soils and tolerates drought and high temperatures.

Although this species does have spines on its leaf tips, its leaves are flexible, making it a friendlier plant to have in a garden setting.

22. Palm

Reminiscent of its cousin, the Joshua tree, palm yucca (Y. decipiens) is another tall, branching, tree-like member of the genus, growing to 20 feet in height.

Inhabiting dry montane habitat from Northern Mexico north to Colorado, this species is hardy in Zones 8 to 11.

Not commonly seen in cultivation, Y. decipiens has the same requirements as its desert-dwelling relatives but is not quite as striking.

23. Plains

Native to the grasslands and deserts of the American Southwest, plains yucca or soapweed (Y. glauca) is culturally important to an array of native peoples.

The fibers from its leaves were used for basket making, and a mashed preparation of its roots was used as soap.

Y. glauca grows to about four feet tall and about two feet wide. Its scientific name is a nod to its leaves which can be waxy, and pale green in coloration.

Hardy in USDA Zones 4 to 10, this species is capable of growing across a wide range of climatic zones, given adequately draining soils.

24. Soaptree

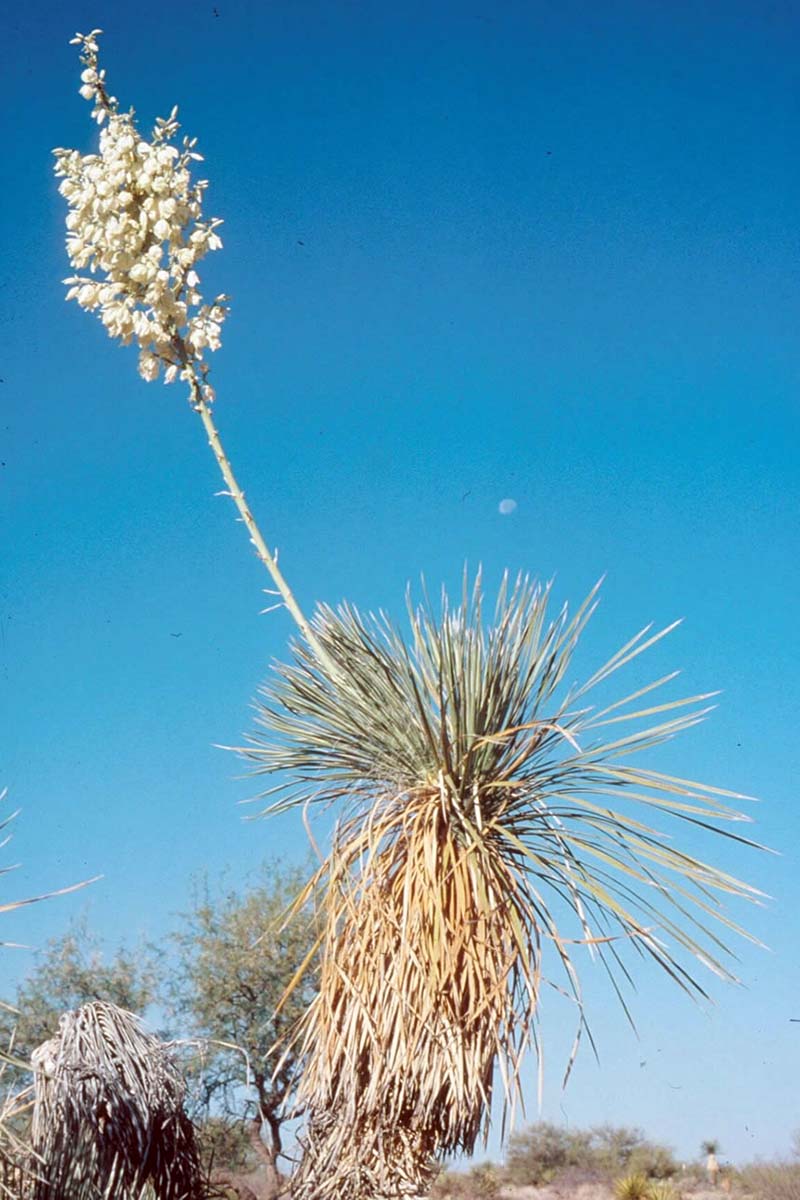

One of the most attractive, fine-leaved yuccas, soaptree yucca (Y. elata) has a tall, shaggy trunk with a dense rosette of leaves perched on top.

The flowering spike erupts from the center of the rosette, ascending to a lofty 18 feet.

Utilized for the sudsy lather its mashed roots make, this species is easily grown in freely draining, dry soils like the rest of its brethren.

Hailing from Arizona, Texas, and Mexico, Y. elata is hardy in Zones 6 to 11.

25. Spanish Dagger

Here, thank goodness, is an example of a humidity-tolerant yucca. Eastern gardeners, rejoice!

Bearing all the hallmarks of its genus, the Spanish dagger (Y. gloriosa) has a handsome rosette of pointed, strap-shaped leaves, and a striking spike of creamy white bell-shaped flowers come late spring.

Growing up to 16 feet in height, this species will eventually, very slowly, grow a short trunk and can develop lateral branches at ground level.

A popular variety, Y. gloriosa var. recurvifolia has recurved, or backward bending, leaves. This variety’s abundant, drooping, leathery leaves have given it the common name “weeping” or “curved” yucca.

Hardy in Zones 7 to 11, Spanish dagger can also tolerate frost.

Although highly drought tolerant and happier in arid soils like the rest of its genus, this species can tolerate more regular rainfall so long as drainage is adequate.

26. Spineless

Finally, a yucca you can hug! Spineless yucca (Y. elephantipes, syn. Y. gigantea) is as friendly as its common name suggests, boasting smooth, un-spiny, shiny leaves atop a short trunk.

Though Y. elephantipes rarely flowers in a pot, it’s easy to care for and performs as a houseplant in all other ways.

So if you don’t have the freely draining soils and mild temperatures this species requires as an outdoor specimen, grow it indoors!

Make sure to use very low nutrient soils high in perlite or other additives that aid drainage and place it in full sun.

Y. elephantipes is hardy in Zones 9 to 10 and can reach 15 feet tall and over 25 feet wide, if it is given the space to branch laterally.

In its native Mexico it has been known to grow 30 feet tall and is considered one of the tallest members of its genus.

27. Thompson’s

Similar to beaked yucca but a little bit smaller, Thompson’s yucca (Y. thompsoniana) reaches heights of about 12 feet and can spread six feet wide.

A trunk-forming type, this species produces a flower spike at the center of its rosettes in late spring, and blooms in early summer.

Native to the rocky hills, slopes, and plains of Texas, New Mexico, and Mexico, Y. thompsoniana is found on limestone outcroppings and in rocky, freely draining soils where it receives plenty of sunlight.

Hardy in Zones 7 to 11, this species can tolerate frost, but will be much more vigorous in warmer, arid conditions.

28. Twisted

Twisted yucca (Y. rupicola) gets its name from its wavy, narrow, olive-green leaves which twist as they age.

Endemic to southern Texas and northeastern Mexico, this small yucca grows two feet tall and two feet wide.

Once its flower spike emerges in late spring, this otherwise petite member of the genus adds another three feet of height.

Inhabiting rocky places with dry, nutrient-poor soils, this plant’s specific epithet means rock-dweller, or cliff-dweller.

Y. rupicola does not produce a trunk, but forms small colonies from underground rhizomes. Hardy in Zones 6 to 10, it’s an excellent choice for rock gardens in areas with minimal rainfall.

Durable and Diverse

This list is just a small sample of the plentiful, low-maintenance members of the Yucca genus.

Although there are only minor variations in how some of the different species look, there is abundant genetic diversity present in the genus.

If you live in a climate zone with ample rainfall or humid summers, try planting one of these tough succulents in a pot so its substrate can drain quickly. If you are lucky enough to have a rocky or sandy hillside, give yucca a try there!

Remember, these plants thrive in places other plants can’t. They’ll light up an otherwise barren landscape with their flower-packed displays.

Just pay attention to the minimum hardiness requirements of the species you select and watch it on the watering.

Where have you successfully grown yucca in your garden? Which members of the genus have you seen on hikes at home? Leave us a comment below, or ask us a question to help you on your yucca growing journey.

To learn more about bringing yuccas to your backyard, check these articles out next: