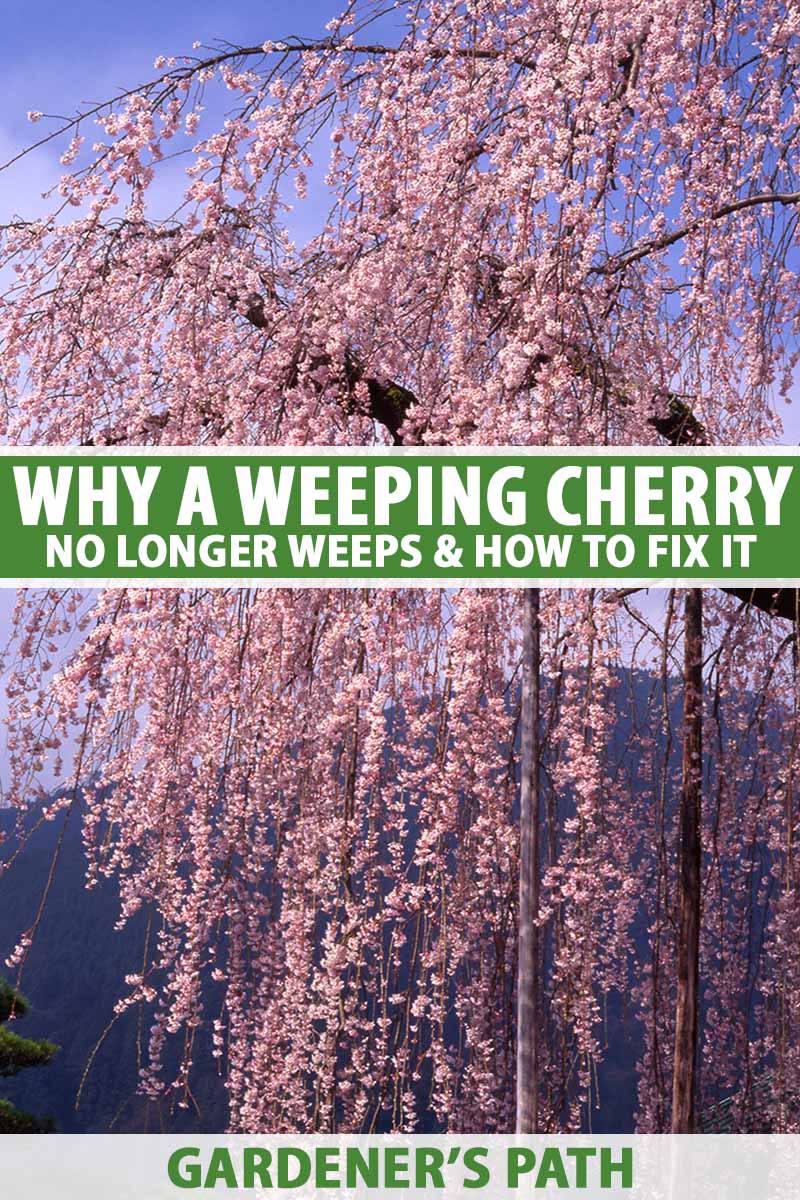

Weeping cherries are iconic. Those fountain-like sprays of magnificent blossoms are unlike anything else.

They seem like something straight out of our favorite fairytales and it’s little wonder they often feature in them.

I guess it shouldn’t come as a surprise, given their otherworldly beauty, that they don’t actually occur in nature.

That’s right – weeping cherries don’t naturally grow that way. They’re produced using grafting and judicious pruning. Then, they’re shipped off to the consumer to plant and enjoy.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Sometimes, those weeping beauties decide that they want to grow upright.

You’ve probably seen them. The ones that have a few errant stems poking out the top that just don’t seem to fit in with the rest of the tree.

We’re going to go over why that happens and what you can do to fix it. Coming up, here’s what we’ll discuss:

What You’ll Learn

Don’t worry, your beloved tree will be back to weeping in no time. To start with, let’s go into a bit more detail about how these trees are made.

And if you need a refresher on how to care for weeping cherries, check out our growing guide.

What Makes Cherry Trees Weep?

This is going to help us figure out how to handle the situation if we understand what it is that makes ornamental cherry trees weep in the first place.

To do that, we need to discuss apical dominance.

Apical dominance means the tip of the main, tallest shoot controls the dormancy and growth of buds that sit lower on the stem. They do this using a hormone called auxin.

Some species have strong apical dominance, meaning they are primarily composed of a single stem with little or no branching. Other plants show partial or even weak dominance. Sunflowers have strong apical dominance. Fuchsia has weak apical dominance.

Prunus species like ornamental cherries are somewhere on the partial to strong dominance end of the spectrum. That means, if we disturb the main growing stem by pruning it, it will send growth hormone to lower branches.

Growers take advantage of this to force a tree to have a stronger weeping habit than it would normally. They trim off the main growing stem to force the auxins into the lower branches and encourage weeping.

Then, there is grafting.

All modern weeping cherries except for some hybrid cultivars are grafted. There just isn’t a cherry tree in nature that naturally has the familiar weeping form.

The grower will make a horizontal graft at the top of the stem of a rootstock tree to create that waterfall-like shape that we so adore. The rootstock would produce upright growth if it was allowed to grow naturally rather than having a different type of tree grafted onto the top.

But sometimes, grafted plants of all species will revert, which means the rootstock sends out growth that overtakes the scion.

Let’s talk about this phenomenon next, because it’s the most common reason for a weeping cherry to form upright growth.

Reversion

As we mentioned, unless you are growing certain cultivars, your plant was propagated through a technique known as grafting.

And if your tree is producing upright growth in the canopy, it’s usually a problem with reversion. That means a grafted tree is trying to return to its roots.

Since these grafts are positioned higher up rather than just above the roots at the crown, as with plants like roses, reversion can happen in multiple areas.

Anywhere from the graft union down can produce upright growth consistent with what the rootstock species would have.

You can usually see the graft union inside the main mass of branches. It will look like a big, roundish, knobby growth. If you see straight stems growing anywhere below that knob, this is due to reversion.

Reverted stems are usually really obvious because the leaves will also look different from the rest of the tree, as will the blossoms. These branches might even bloom at a different time from the rest. And these growths are usually much more vigorous than the weeping parts.

If you catch them early, you can just cut off the reverted stems and go about your day. Cut them as close and as cleanly as you can to the growth point.

Then, you’re going to need to keep a sharp eye on your plant and prune it regularly, because those growths are going to keep happening. Once the rootstock gets a taste of freedom, it isn’t about to give it up.

If you neglect your duties and too many reverted stems start to grow, you will lose the shape of the tree, and it will essentially become an upright cherry. You’ll have to buy a new weeper if you want to start over.

Maybe these growths are taking a different form? When reversion happens at the ground level, we call it suckering. We’ll talk about that next.

Suckers

Suckers go hand in hand with grafting. These are just reversions that come directly off the roots rather than the branches.

A tree that is heavily suckering is often one that has been seriously damaged. Plants send out suckers as a way of starting new ones when the main one is weakened.

Storm damage, overzealous pruning, pests, drought, disease, and any other form of stress can cause suckers to form.

That means even after you remove the suckers – which you should do – it will likely continue to form new ones.

If it’s constantly forming a lot of new suckers, you might consider giving up on the tree. I know it hurts, but at a certain point, you’re fighting a losing battle.

That leads us to the least common form of upright growth, one which is also related to stress: water sprouts.

Water Sprouts

Water sprouts form in the canopy. Instead of emerging at the root level, these form from the buds of the plant when a plant is stressed, which can be caused by severe pruning, drought, storm damage, or breakage.

Water sprouts can be difficult to distinguish from reversion, but they should be treated in the same way: with the ol’ chop.

Water sprouts often form above the graft, though not always. If it happens above the graft union, it’s definitely water sprouts and not reversion that you’re dealing with.

This is typically the problem if you’re growing a specimen that isn’t grafted.

Sometimes All We Want Is a Good Weep

Normally, unless you’re watching the Hallmark Channel, I’d say habitual weeping is a bad thing. But in this case, it’s the best!

And none of us want to see our ornamental cherries go from a fountain of flowers to a barren bundle of sticks.

Which problem are you facing with your cherry? Do you have one that’s trying to revert back to the rootstock? Or maybe yours is sending up stress suckers? Share your experience in the comments section below.

If you’d like to learn a bit more about our more upright cherry tree friends, both flowering and fruiting, check out these guides next: