Vaccinium corymbosum

To heck with apples, eating some blueberries each day is what keeps the doctor away!

Or at least that’s what professor of nutrition and epidemiology Dr. Eric Rimm and his colleagues at Harvard Medical School announced, based on the results of a study published in 2013.

Truth be told, I’d eat them even if they weren’t so darned good for me. A fresh blueberry bursting in my mouth is the stuff of summer. And if you’re as big a fan as I am, perhaps you’ve gone berry picking before.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

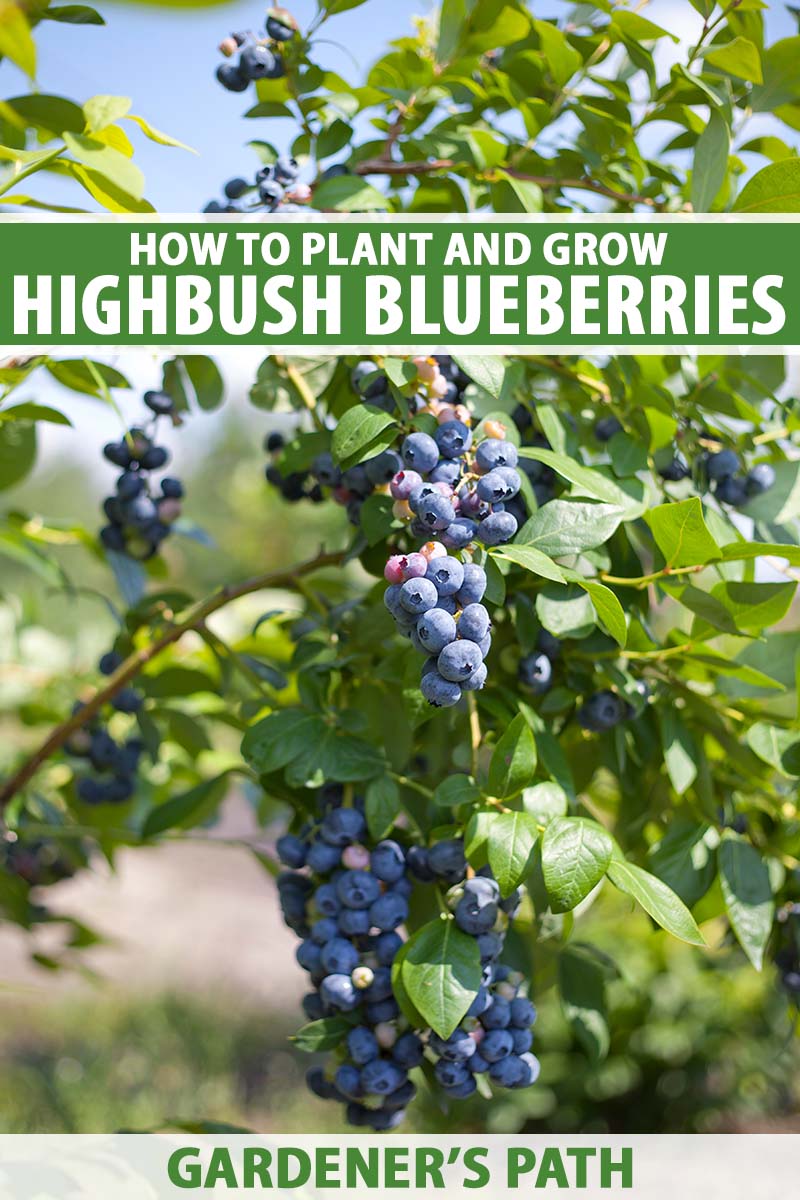

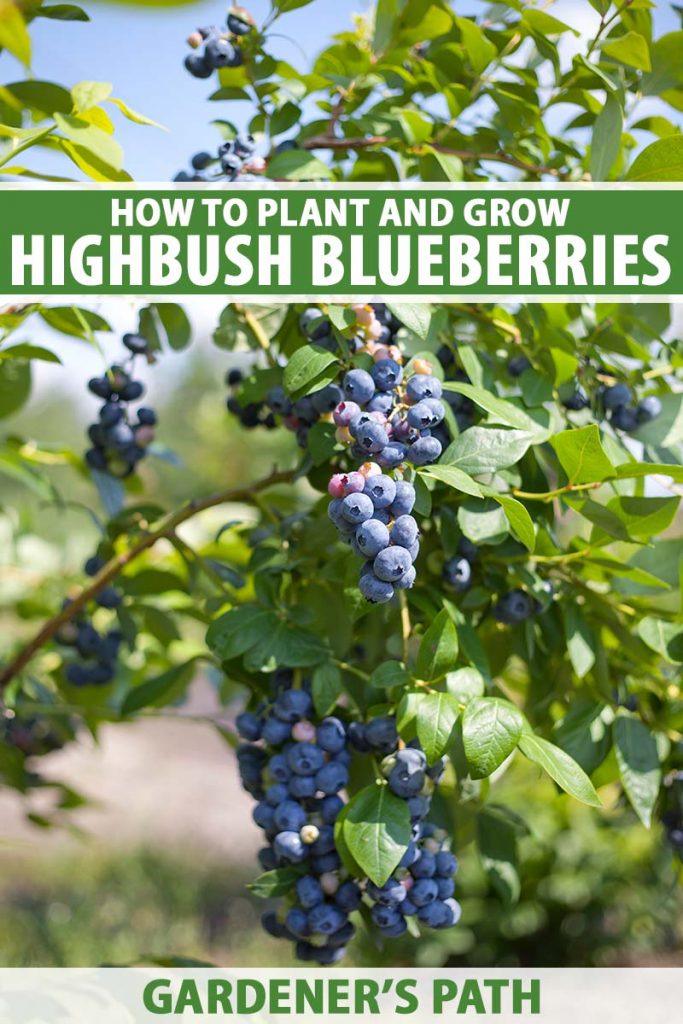

If you’ve ever driven past or visited a farm with rows of tall blueberry shrubs, those were probably highbush plants. Of all the available species and varieties, northern highbush is the most common type cultivated commercially.

That’s because these will grow in a wide range of climates and are self-fruitful, producing a large harvest of delicious berries even without a companion pollinator planted nearby.

So how do you keep a highbush plant happy and productive if you decide to grow this type yourself? We’ll cover everything you need to know. Here’s what’s up ahead:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Highbush Blueberries?

Vaccinium corymbosum is perhaps the most well-known species of blueberry, and the juicy berries they produce in the summer are the most common variety you’ll find at grocery stores.

The deciduous woody shrubs can reach up to eight feet tall at maturity.

These plants were bred to handle cool temperatures and to produce a high yield of sweet, large berries perfect for eating off the bush or using in recipes.

Highbush blueberries are easier to harvest than lowbush blueberries because you don’t have to squat down to pick them, and yields are typically higher.

These are divided into northern and southern types.

Northern types are grown widely in the eastern US, in the Mid-Atlantic region and New England in Zones 4 to 8, though some will grow in Zone 3.

Southern highbush types grow best in Zones 5 to 8, and may exhibit evergreen or deciduous foliage. These were bred and introduced in the 1980s by growers in southern states who wanted to grow this species in a warmer climate.

There are also hybrids of highbush and lowbush varieties, which are known as half-high blueberries.

When selecting your plants, in addition to the growing zone, you also need to keep “chill hours” in mind, or the number of hours each winter that the temperature falls between 32 and 45°F.

Blueberries require a certain number of chill hours to produce fruit. Though there are some exceptions, northern plants typically need more, while southern varieties require fewer chill hours.

Cultivation and History

Blueberry plants are native to eastern North America, and indigenous populations there both ate the fruits raw and used them to make a nutritious mash of berries and animal fat called pemmican.

Until 1911, all blueberries growing in North America were the wild, uncultivated lowbush type.

Highbushes came about when the daughter of a cranberry farmer named Elizabeth Coleman White decided to work with botanist Frederick V. Colville to cultivate a taller, more productive variety that she and her family could harvest to sell along with their cranberries.

Enter the highbush blueberry, which has become the dominant type for commercial growers in the US.

Chances are, if you’re picking up that familiar clamshell of blueberries at the grocery store, it’s filled with a type of highbush berry.

Propagation

There are several easy ways to propagate highbush blueberries, including rooting cuttings taken from a mature plant, or purchasing a bare root plant or transplant.

You can also grow them from seed, but the resulting plant might not grow true to type, and it takes a while. Still, it’s a fun project to do with the kids.

By Cuttings

If you have a local wild plant that you think tastes particularly good, you can reproduce it through cuttings.

Just be sure to check with your local government or the landowner before you start cutting plants that don’t belong to you.

You can also reproduce a hybrid plant using this method.

By Bare Root

You can purchase bare root plants from many nurseries and retailers.

The advantage with bare roots is that they cost less than transplants, but they will be ready for harvest in about the same amount of time.

You can learn more about propagating blueberry bushes in our guide.

Transplanting

Transplanting is a quick method to get from planting to eating your harvest.

We have an entire guide on how to transplant blueberries to help you succeed.

How to Grow Highbush Blueberry Bushes

You may have heard that blueberries thrive in acidic soil, and that’s true. They need a soil pH of between 4.5 and 5.5.

If you don’t have earth that is that acidic naturally, you’ll need to amend it. Finely ground sulfur or aluminum sulfate are reliable additives that you can use to lower soil pH.

Our guide to growing blueberries has more tips for helping you to create the right conditions for your plants, and it covers everything from prepping the soil for planting to pruning and mulching.

Almost all northern highbush cultivars are self-fertile, so they don’t need a companion to produce a bush full of berries. However, a companion can help increase the number and the size of the fruit.

Southern highbush plants, on the other hand, need a pollination pal if you want fruit. The trick is to pick two (or more) plants that bloom at about the same time.

Here are some common cultivars that make good friends:

- ‘Georgia Dawn’ and ‘Rebel’

- ‘Palmetto’ or ‘Southern Splendour’ and ‘Suziblue’

- ‘Blue Suede’ and ‘Camellia’

- ‘Summer Sunset’ and ‘Titan’

Standard plants should be spaced about four to six feet apart. Smaller cultivars can be planted two to four feet apart.

Blueberries naturally grow along the edges of waterways, or even on hills in swampy areas, where their roots won’t be submerged.

That should tell you that while they like a lot of water, they don’t appreciate it when their roots are sitting in standing water.

Ideally, you should place your plants in an area with a slight slope so water drains away from the roots. Frost also tends to settle in low areas and at the base of hills, so a higher point on a slope is a good location for preventing frost damage as well.

Keep in mind, however, that wind is typically more severe on hilltops. Wind can damage your plants, so position them next to a windbreak if you don’t have a protective slope available. A row of acid-loving conifers or a stone wall are ideal options.

Not only is it nice to be able to grow these plants near ponds, waterways, and other areas where veggies might not thrive, they’ll also attract local wildlife. But keep this in mind, since you may wind up sharing your harvest!

While they can grow in partial shade, a full sun location encourages more blossoms, which translates into more fruit. It also means more brightly colored fall leaves.

Though some larger highbush varieties have roots that can reach as deep as two feet, in general, these have shallow roots with most of the root structure located in the top foot of soil.

That means they need regular watering.

Plants need one to two inches of water a week, assuming you haven’t gotten any rain. If you aren’t sure how much precipitation you’ve received, try using a rain gauge.

You should also add a finely chopped wood mulch around your plants to help retain water (more on that below).

Don’t use your yard compost, since this usually has a pH that is too high (or alkaline) for growing blueberries. Spread the wood matter out about three feet wide around plants, and pile it three inches deep.

In the first year, you can add ammonium sulfate fertilizer in June or July, applying granules in a circle 15 inches away from the base of the plant.

But remember, you should test your soil first to determine if fertilizer is necessary.

Ammonium sulfate helps lower pH and adds nitrogen. Add one ounce per plant.

After that, fertilize while plants are blooming. You can apply half of the fertilizer when plants just start to bloom and then again in four weeks, or you can fertilize all at once two weeks after blossoms have emerged.

Fertilizing too early can result in failure to take up the nutrients you’ve provided.

Two-year-old plants need a 4-6-4 (NPK) organic fertilizer applied at a rate of about six ounces per plant, adding two additional ounces every year to follow until you reach a peak of 16 ounces.

You may need to apply more nitrogen if you are using fresh sawdust mulch, since it can tie up nitrogen. Use a half teaspoon of blood meal as a side dressing.

I like Down to Earth’s blood meal. If you want some for your garden, Arbico Organics carries containers in a variety of sizes, from a half pound to 50 pounds.

Be careful not to add too much nitrogen, because blueberry plants work together with a fungus in the soil called Ericoid endomycorrhizae to absorb nutrients.

Too much nitrogen can reduce the fungal population, which causes a whole host of problems.

That’s why yearly soil testing to determine the nitrogen level of your soil is recommended before you apply fertilizer.

Find more tips on fertilizing blueberry plants here.

Highbush blueberries produce best with regular pruning. And be sure to refresh the mulch annually in the spring, gradually building it up to a depth of about six inches from the original three inches of material that you added.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full sun, preferably on a slope.

- Maintain soil pH between 4.5 to 5.5.

- Provide one to two inches of water per week in the absence of rain.

- Regular pruning is essential.

Cultivars to Select

There are more than 50 cultivars of highbush blueberries available, a testament to how important they are as a commercial crop. Because there are so many varieties, you might want to check with local experts to see which are best suited to your area.

Remember that some plants, typically the southern cultivars, need companions to produce. All plants need a specific range of chill hours to fruit, and these are noted below.

Here are some of the most popular types. You can find more in our roundup of recommended varieties.

Bluegold

‘Bluegold’ is a northern cultivar that matures late in the season. It has excellent flavor with firm, medium-sized fruits that are ideal for freezing.

This variety grows best in Zones 4 to 7, requires 800-1,000 chill hours, and reaches heights of up to six feet tall. Watch out, though – it’s highly susceptible to blueberry shock virus.

You can find plants in #1 containers available at Nature Hills Nursery.

Duke

‘Duke’ produces firm fruit and is an abundant producer, which is probably why it’s one of the most widely planted northern varieties.

It blooms late and fruit ripens early, which means it doesn’t run the risk of being damaged by late spring frosts as often as early blooming types do.

It grows best in Zones 4 to 7, needs about 800 to 1,000 chill hours, and may require trellising because of its heavy yields. It grows to be about six feet tall at maturity.

One drawback is that it’s particularly sensitive to pH and nutrition in the soil. If you fail to provide what it needs, it won’t fruit or your harvest will be smaller than usual.

You can find plants available at Burpee, and in #1 and #3 containers at Nature Hills Nursery.

Ivanhoe

‘Ivanhoe’ berries are ideal for use in desserts because they’re so sweet, with a bold flavor.

The firm, medium-to-large berries are tender and they don’t store well, which is one reason why this cultivar has fallen out of favor with commercial growers.

But this isn’t a problem if you’re growing them yourself, and enjoying them straight off the bush!

This northern variety does well in Zones 5 to 8 and grows to be extremely tall, with some plants reaching eight feet in ideal conditions. Plant in regions where they will get about 800 chill hours.

Jersey

‘Jersey’ is one of the more common and oldest northern highbush varieties. It grows upright and produces large, sweet berries with an excellent flavor.

It’s exceptionally hardy, grows well in Zones 4 to 7, and needs 800 to 1,000 chill hours.

It can also reach up to eight feet tall, but keeping it pruned to six feet is recommended, to make harvesting easier and to encourage the plant to focus on producing fruit rather than gaining more height.

Sound good? You can purchase these plants from Burpee.

Midnight Cascade

‘Midnight Cascade’ is unique in that it’s the first commercially available blueberry suited to growing in hanging baskets.

The medium-sized fruits have a satisfying flavor with a subtle hint of vanilla, and plants have a cascading growth pattern.

This southern type reaches 24 inches tall and grows best in Zones 5 to 9, with 450 chill hours.

Grow with another ‘Midnight Cascade’ plant to facilitate pollination. You can nab these plants over at Nature Hills Nursery.

Northblue

Another option if you’re looking for something smaller, this northern dwarf cultivar reaches about two feet tall at maturity, and grows best in Zones 4 to 8.

It produces large, dark blue fruits with an exceptional flavor.

You can grab an 18- to 30-month-old ‘Northblue’ plant at Nature Hills Nursery.

Northsky

‘Northsky’ grows to be only two feet tall, but despite its small size, you can get up to five pounds of light blue berries per bush during the harvest.

This variety is suited to Zones 3 to 8 and needs 800 to 1,000 chill hours.

If you want to give ‘Northsky’ a go, plants in #1 containers are available at Nature Hills Nursery.

Patriot

‘Patriot’ was developed in Maine, so it grows well there, as you’d expect. It’s a northern cultivar that can tolerate heavy soil and frost.

It has large, flavorful fruits but produces a smaller yield than some other cultivars.

‘Patriot’ grows best in Zones 3 to 7 and will reach four to six feet tall at maturity. Give it 800 to 1,000 chill hours.

If you want ‘Patriot’ for your garden, you can buy plants at Burpee.

Perpetua

‘Perpetua’ grows up to five feet tall at maturity, is suited to Zones 4 to 8, and needs about 600 chill hours.

What sets it apart is that it produces two crops each year: one in midsummer, and another in the fall.

The small berries are intensely sweet.

If you want to add ‘Perpetua’ to your garden, you can find plants available at Nature Hills Nursery.

Managing Pests and Disease

Highbush blueberries specifically suffer from a number of pests and diseases, in addition to the pests and diseases that may bother all plants in the genus.

Pests

Birds and deer are big fans of blueberries of all varieties. Read more in our growing guide for tips to protect your blueberry harvest from hungry herbivores.

In addition to insect pests like maggots, beetles, and caterpillars, highbush blueberries are sometimes attacked by blueberry tip borers.

The larvae of Hendecaneura shawiana hatches in late spring as the new growth starts to harden on plants.

The caterpillars burrow into the canes, chewing up to a foot down the cane by the time winter arrives. They cause new shoots to wilt or arch, and the leaves may turn yellow with red veins.

Prune infected canes to get rid of them. If you notice damage on your plants, cut the affected cane at least a foot down, or trim it away altogether.

Diseases

Keep an eye out for the following diseases.

There are no cultivars available that are resistant to everything, and not all diseases occur in all areas, so you might want to check with your local agricultural extension office to find out what to grow in your area to avoid problems.

Blueberry Mosaic

Blueberry mosaic (BlMaV) is thought to have existed in native plants for centuries. It causes plant growth to become stunted and you’ll see the leaves start to turn yellow, pink, or mottled.

While most varieties are resistant, it does impact a few different cultivars. Since there is no cure for this virus, you must pull infected plants and destroy them.

Blueberry Shock Virus

Blueberry shock virus (BIShV) is common in the Pacific Northwest. It causes blossoms and flowers to die off rapidly during the blooming period.

The foliage will return, but the plant won’t fruit. After a few years, the plant will return to normal, though the virus remains in the tissue.

It’s carried from plant to plant by pollinators and infection sets in when plants are in bloom. Avoid susceptible cultivars and buy certified virus-free seeds or plants.

In the home garden, there isn’t much you can do but let the disease run its course. Commercial operations are often forced to cull plants and start anew so it doesn’t spread.

You can do this, but since the plants will continue producing as normal, you may opt to just live with it.

Chlorosis

Not technically a disease, but rather a physiological disorder caused by a nutrient deficiency, chlorosis occurs when the plant doesn’t receive enough iron and the leaves can’t produce chlorophyll.

You’ll often see yellow or discolored foliage and the plant may be stunted. Leaves may also drop prematurely.

It isn’t necessarily that there isn’t enough iron in the soil, but rather, your plants may be unable to access it because the soil is too alkaline. Anything above a pH of 6.0 may cause a problem.

In the short term, you can spray plants with chelated iron, which you can purchase at your local garden supply store or online.

Follow the manufacturer’s recommendations. In the long term, you may need to add sulfur or iron sulfate to the soil to make it more acidic.

You should also add a layer of sawdust mulch to protect the roots from overheating if you live in an area with temperatures that reach above 85°F.

Stressors like excessive heat reduce root growth and can also cause plants to have difficulty accessing iron in the soil.

Ripe Rot

Ripe rot, sometimes called anthracnose fruit rot, has been devastating to some orchards in the Pacific Northwest.

It’s caused by a fungus called Colletotrichum acutatum, which favors warm, moist conditions. It’s spread by water, whether that’s in the form of rain, humidity, or irrigation.

The first thing you’ll notice is a darkening of new shoot tips, followed by flowers that start to turn brown or black. You may eventually see pink spores on infected berries.

You might miss the pink spores on the plant, but you’re sure to notice them when you harvest the fruit.

Spores are picked up by your hands or tools like clippers and will spread rapidly as you pluck the fruit and move from bush to bush.

Your best defense is to try to improve air circulation and reduce wetness on plants. Don’t water from overhead and keep your plants pruned well.

Make sure to keep bushes spaced well when you plant. You can also use a copper-based fungicide treatment, according to the manufacturer’s directions.

Find more details in our blueberry pest and disease guide.

Harvesting

Highbush blueberries are the earliest species to start ripening, and some are ready to start plucking as early as April in some areas.

Under ideal conditions, with the right soil, water, weather, and minimal damage from pests and diseases, a single bush can produce nearly 20 pounds of berries. Plants can continue to produce for up to 50 years.

Let the berries ripen fully on the plant before picking them.

How will you know that it’s time? If you tug a berry, it should come away readily. Look at the fruit stem; it should be blue, not red or green. The berries should also be matte or dull, not shiny.

Berries growing in a cluster will ripen unevenly, so some will be ready to go and others may need another few days to a week.

Pick the individual berries by hand and gently place them in a bucket or basket.

Berries taste incredible right off the bush when they are warm from the sunshine, but if you don’t plan on eating them right away, stick them in a cool area or in the refrigerator.

This helps to improve their shelf life. Don’t wash the fruits until you are ready to dig in.

Learn more about how to harvest blueberries in this guide.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Recommended uses for this delicious homegrown fruit are pretty broad.

Many of us are sure to love them as a topping on yogurt or oatmeal for breakfast, or as a treat on ice cream or meringues for dessert, but don’t forget that they’re delicious in savory dishes as well!

You can make a sauce using fresh berries that is delicious as a topping on meat or fish. Or put them on soft brie on top of a slice of toast.

Try making blueberry kefir at home, a tasty probiotic beverage.

Our sister site Foodal has the recipe.

Or whip up these blueberry scones for breakfast – you can find the recipe on Foodal.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Perennial berry | Tolerance: | Heavy soil, flooding |

| Native to: | North America | Maintenance: | Medium |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 4-8 | Soil Type: | Sandy, loamy, high in organic matter |

| Season: | Spring-fall | Soil pH: | 4.5-5.5 |

| Exposure: | Full sun to part shade | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Time to Maturity: | 3 years | Attracts: | Butterflies, bees, birds, deer and other herbivores |

| Spacing: | 4-6 feet (standard), 2-4 feet (dwarf varieties) | Companion Planting: | Azaleas, basil, camellias, ornamental grasses, parsley, rhododendrons |

| Planting Depth: | 1/4 inch (seeds), same depth as container (transplants) | Avoid Planting With: | Plants that prefer alkaline soil |

| Height: | 2-8 feet | Family: | Ericaceae |

| Spread: | 1.5-4 feet | Genus: | Vaccinium |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Species: | Corymbosum |

| Common Pests: | Birds, blueberry maggots, blueberry tip borers, deer, Japanese beetles, yellow-necked caterpillars | Common Diseases: | Blueberry mosaic virus, blueberry shock virus, botrytis blight, mummy berry, ripe rot |

Prolific and Beautiful

If you’re willing to put in the effort, highbush blueberries will give you more fruit than you can probably handle, all while adding beauty to your yard.

On top of that, I think homegrown blueberries are far superior to the ones you can buy at the store.

I can’t wait to hear how your berry plants do – and I have no doubt that you’ll be eating homegrown fruit by the handful in no time. Let me know in the comments section below!

And for more information on growing blueberries and other berries in your garden, check out these guides next:

Good article