Black rot of cabbage is a bacterial infection that causes extensive damage to brassicas, aka cruciferous vegetables, including bok choy, broccoli, cauliflower, kale, and turnip greens.

Caused by Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris (or Xcc), the bacteria enters a cabbage via a leaf pore or wound, such as a broken leaf. It spreads systemically, rendering all plant tissue vulnerable.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

In our guide to growing cabbage, we offer information on how to cultivate this cool-weather crop in your garden.

In this article, we zero in on cabbage black rot disease, ways to inhibit it, and how to deal with an outbreak.

Here’s what’s in store.

What You’ll Learn

We’ll begin with an overview of bacterial black rot.

A Brutal Bacterial Infection

Let’s get right to the point. This disease is so pervasive and challenging that by the time we recognize it in the garden, there’s a high probability that it’s already too late to salvage not only the visibly affected plant, but most likely, your entire cabbage crop and other brassicas in the vicinity.

And after removing affected plants, the ground is contaminated and unable to sustain healthy cruciferous vegetables for the next four years.

Folks, this is huge!

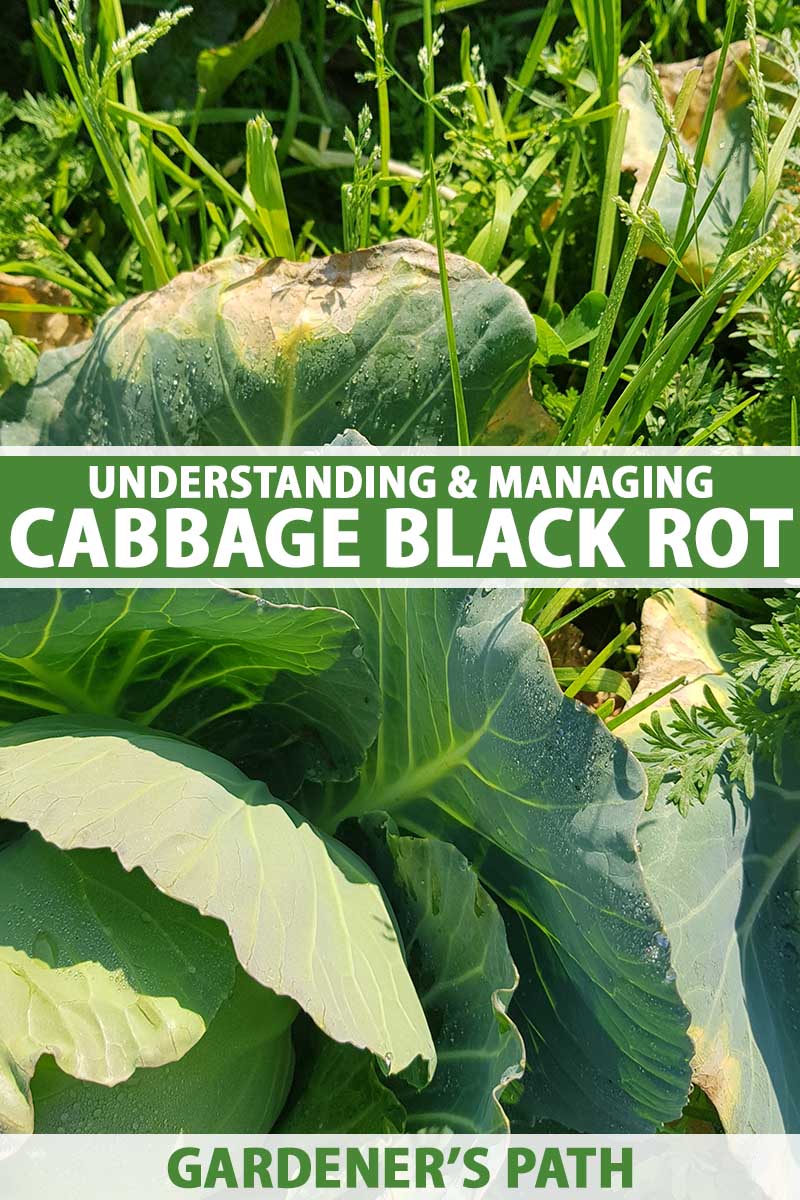

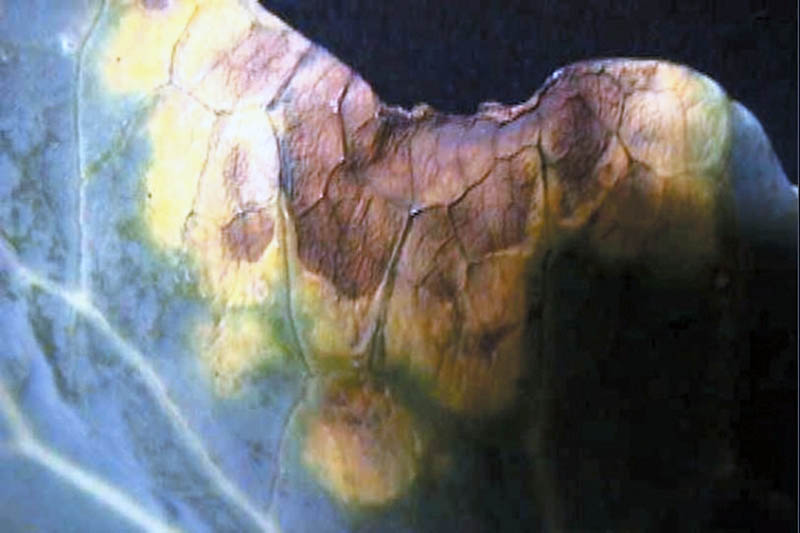

The visible signs of the disease are unmistakable. At any point during a plant’s maturation, from germination to heading, the leaves can develop yellow or chlorotic patches on the outer edges or margins.

The patches form V-shapes that align with the leaf veins. After yellowing, the leaf tissue becomes necrotic, turning brown and dry.

At the same time, the bacteria exude sweet, sticky xanthan which clogs the veins, blackening and rotting them, hence the name “black rot.”

Yes, readers, we said xanthan – as in gum. When this brassica-battering bacterium grows on a carbohydrate, it produces the food thickening agent, xanthan gum!

But that’s another story.

By the time the leaves begin to droop and die, a cabbage’s stem and roots are already compromised, because the sneak attack begins at the soil level and works its way up.

And as if that isn’t bad enough, guttation, the nocturnal process of releasing tiny drops of sap we call morning dew, causes a leaf to exude infectious bacteria that land on the soil and maybe other brassicas.

Yikes! What’s a gardener to do?

Let’s find out.

Avoidance Measures

In order to avoid contracting this disease, we need to consider the conditions favorable to its development and ways to address them.

One way bacteria can take a firm hold is through contaminated seed.

The best way to avoid letting a pathogen have the upper hand from the start is to purchase disease-resistant seed that has been bred for above-average tolerance to black rot. It may also be heat treated to destroy bacteria within the seed.

If your seed has not been heat treated, you can do it yourself.

Soak the cabbage seeds in 122°F water for 25 minutes, as recommended by the pros in the UMASS Extension Vegetable Program of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment.

This is also an effective means of controlling other cabbage diseases including Alternaria leaf spot, bacterial leaf spot, and black leg.

Xcc can winter over on infected plant material, especially when it is turned under the soil.

Weeding and removing debris from the garden go a long way toward deterring infestation by insects that may be vectors, or carriers of plant diseases, like the sap-sucking aphid.

Speaking of weeds, in addition to the vegetables with which most people are familiar, there are weeds in the brassica family that are also prone to black rot.

Wild versions of mustard and radish can harbor disease just like cultivated varieties of mustard greens and horseradish.

Rotating cabbages and other cruciferous plants to a new location every two to three years is a smart way to reduce the risk of infection in general.

In the event of an Xcc outbreak, don’t plant brassicas on the same site for at least four years. It’s fine to sow seeds of other plant families that aren’t prone to black rot.

Another way to inhibit Xcc development is to avoid excess moisture on and around cabbages. Use a hose or watering can aimed at the soil, and avoid splashing potentially bacteria-contaminated water on the leaves.

Avoid overwatering, especially in humid weather, as excessively moist conditions are favorable for bacterial growth.

Sow plants in full sun with mature dimensions in mind, to avoid moisture buildup between them.

Consider a preventative pre-application of a copper-containing antibacterial treatment. Apply it before you notice leaf symptoms.

In addition or as an alternative to this, you may also treat plants with a product containing copper at the first sign of chlorosis. While it’s not a cure, treatment may inhibit the spread of disease to neighboring flora.

If a mature head becomes infected close to harvest time, you may be able to remove the affected outermost leaves and harvest a quality cabbage head from within them.

Discard any damaged, discolored, distorted, malodorous, or rotten leaves, and keep them out of your compost pile to prevent further spread.

Damage Control

If you find an infected plant, wear disposable gloves and washable garden shoes to deal with it. Dig it up and seal it in a plastic trash bag for disposal.

Sanitize all equipment with a 10 percent bleach solution (one part bleach to 10 parts water) to avoid spreading Xcc throughout the garden.

After an infected plant is removed, apply a copper-containing treatment to others in close proximity.

A Little TLC to Beat the Dreaded Xcc

A little TLC goes a long way toward preventing the Xcc pathogen from making inroads into a vegetable patch.

To recap:

Remember to start with quality seed and take the time to heat treat it if necessary

Keep the garden weeded and free of unwanted debris. Remember that weedy wild brassicas are potential carriers and spreaders of Xcc.

Rotate crops regularly.

Avoid overwatering and getting water on the foliage.

Space plants adequately to inhibit moisture buildup.

Apply a copper-containing treatment to prevent and inhibit the spread of Xcc.

Take out your garden planner and outline a proactive regimen for this year’s cabbage patch.

Remember that cabbage black rot is a fatal plant disease that can destroy many cruciferous vegetables. An outbreak may lead to an enormous amount of cleanup, yield loss, and heartache.

Please do not consume leaves that show signs of disease, such as leaf damage, discoloration, distortion, a foul odor, or rotting.

It can be difficult to diagnose a plant disease. When in doubt, contact your local agricultural extension for confirmation before taking action.

Have you had a bout of black rot in your cabbage patch? Please share your experience in the comments section below.

If you found this guide informative and would like to learn more about growing cabbage in your garden, we recommend the following:

So there’s no specific chemical to cure black rot?

Hi Usman4life –

Black rot is bacterial, so fungicides are ineffective.

There are copper-based bactericides, but they can damage crops, and bacteria can develop resistance to them.

Using disease-resistant seed and practicing the avoidance measures discussed are the best ways to grow healthy brassicas.