Eutrema japonicum

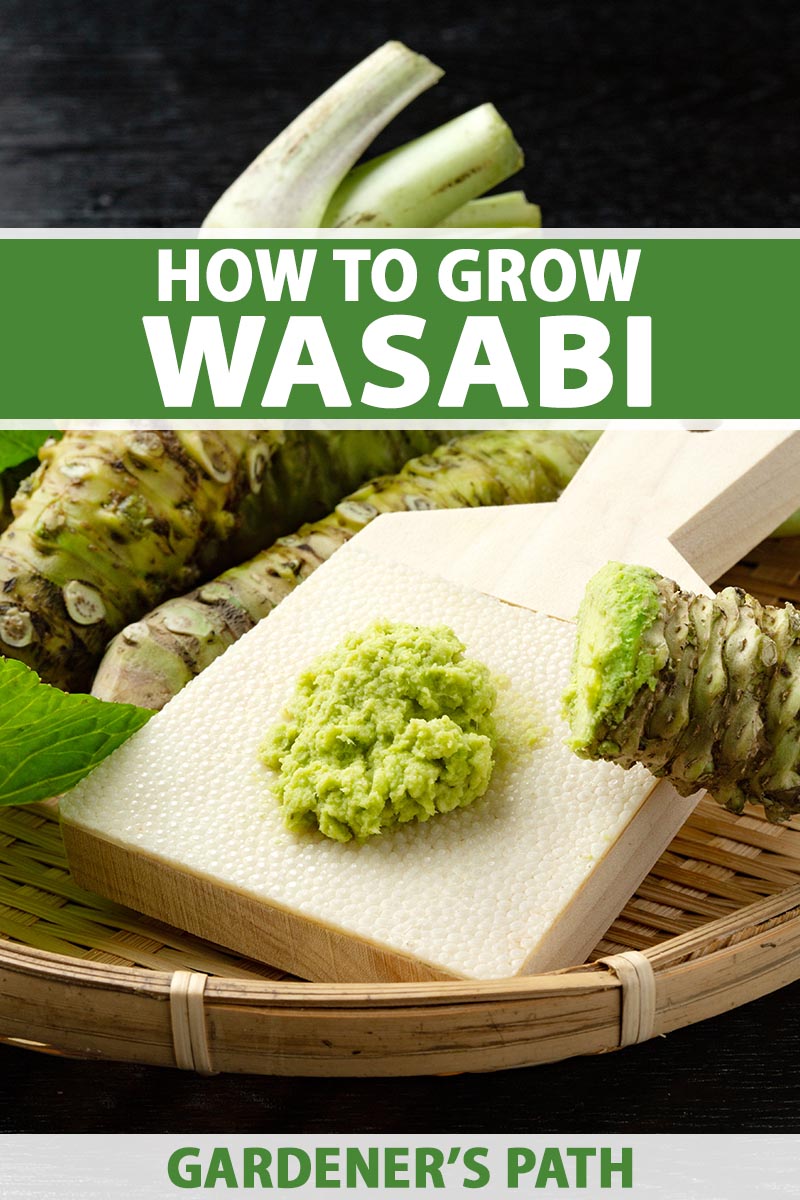

I remember the first time I had a bit of real wasabi. Unlike the neon green stuff I was so familiar with, it had an herbal complexity that I was totally unprepared for. It was, as they say, a revelation.

If you’ve never tasted real wasabi before, you’re in for a treat. The delicious edible leaves, stems, and flowers are just a special bonus, and one that is nearly impossible to find in stores in the US.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

It’s a good thing this herbaceous wonder is so incredibly tasty, because it’s a bit demanding in terms of the environmental conditions it requires to grow well.

You either really have to love wasabi or you have to love a gardening challenge if you plan on growing this marvel.

That’s not to scare you off. In the right climate, it’s actually not as difficult as its reputation suggests. If you’re giving it a go in, say, New Mexico, you have to prepare yourself for some work. But the rewards are oh-so worth it. No pain, no gain, right?!

If I haven’t sent you running for the hills, let’s get started on our adventure. Here’s what we’re going to talk about:

What You’ll Learn

In reality, it’s not the plants themselves that are difficult to grow if you don’t mind keeping them in containers.

If you can make mustard or horseradish thrive, this plant isn’t much different, and you’ll be drowning in tasty leaves and stems. But growing a magnificent rhizome worth dabbing on the finest fish? That’s a bit more challenging.

We’ll walk you through it.

What Is Wasabi?

Wasabi (Eutrema japonicum syn. E. japonica, Wasabia japonica) is a member of the brassica family, Brassicaceae, and it is closely related to mustard.

Famously difficult to cultivate, it is only grown commercially in the US in parts of the rainy Oregon coast, and in North Carolina and Tennessee in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

In Canada, it’s grown in parts of coastal British Columbia.

Don’t let that scare you off! You can grow wasabi anywhere, though you might need to baby these plants if you live somewhere hot, dry, or extremely cold.

These herbaceous veggies originally grew wild in Japan, parts of Russia, and South Korea near streambeds in temperate climates that rarely climb above 80°F or drop below freezing.

Now, having said that, I can personally attest to the fact that some cultivars can survive in warmer and colder regions.

My wasabi sat outside through weeks of freezing temps this last winter. One night even dropped down to 25°F.

I covered my plants with cardboard during the coldest nights, but left them out otherwise. They were buried by a foot of snow, and in the same year, were subjected to temperatures in the high 90s. It was a weird year, climate-wise, in my neck of the woods.

Some of the leaves burned at the edges a bit in the heat, but my plants were fine otherwise.

USDA Hardiness Zones 8 to 10 are ideal, and the best-tasting rhizomes grow in temperatures ranging from 43 to 68°F.

Hotter or colder temperatures can impact the flavor and texture of the rhizome. Extreme temperatures also leave the plant susceptible to fungal issues.

So, yes. You can grow wasabi if you don’t have the perfect climate. You’ll need to keep your plants in containers and you’ll have to be prepared to move them during extreme weather, but it can be done.

Alternatively, you can grow them indoors as well. They don’t need a lot of light and they prefer temperatures right around where most humans like it. Plus, they’re pretty!

They have big, kidney-shaped, edible leaves. In the spring, they have long stalks with small, also edible, white flowers, followed by seeds.

Seeds will only develop properly if the temperature drops low enough for vernalization, however. The leaf stems (petioles) can be green, purple, or red.

The plants can grow to about two feet tall and spread through plantlets on underground rhizomes. Each mother plant can produce up to two dozen of these. Underground, you’ll find a finger-shaped rhizome, which is actually a stem, that can be grated to release that marvelous, spicy magic.

If you’ve only ever had the typical wasabi substitute at a sushi restaurant, which is made using horseradish, you only have an inkling of how delicious real wasabi can be.

It lacks that intense bite that makes your sinuses weep and has a more complex, herbal, sweeter flavor.

You can eat a nibble of fresh wasabi and it won’t make your eyes water. It still has that spicy, sinus-based kick, but it’s just more subtle. The kick also fades faster than with mustard or horseradish.

That spicy flavor comes from the compound allyl isothiocyanate, which is felt more nasally than on the tongue as with chili peppers.

Those who cultivate wasabi commercially grow it in semi-aquatic conditions known as sawa, which means swamp in Japanese. The resulting rhizomes are considered superior to the stuff grown in the ground, which is called oka, for blossom in Japanese.

It might just be the pride of being able to grow such a notoriously difficult veggie, but the stuff I’ve grown tastes every bit as good as what I’ve bought at high-end sushi places.

Okay, I’m biased, but it’s still awfully good despite being cultivated in soil.

Cultivation and History

Wasabi was originally mentioned in texts as a medicinal plant and appears in Japanese writings from around 600 AD.

It wasn’t until the 17th or 18th century that people in Japan started cultivating it. By the early 1800s, people realized that it made an excellent addition to raw fish.

It’s not clear if people first used it for the flavor or for its antimicrobial properties. Perhaps a bit of both?

While we may not have had the scientific tools to prove it hundreds of years ago, people likely noticed that raw fish eaten with wasabi was less likely to make them sick.

Recent studies confirm what many had already figured out.

For instance, a study by Zhongjing Lu, Christopher R. Dockery, Michael Crosby, Katherine Chavarria, Brett Patterson, and Matthew Giedd, researchers from Kennesaw State University in Georgia, found wasabi to be effective against E. coli (Escherichia coli O157:H7) and staph (Staphylococcus aureus).

They published their findings in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology and while I appreciate their efforts, I’d probably be stuffing my face with wasabi even if it wasn’t an antimicrobial powerhouse.

Wasabi Plant Propagation

You can technically grow wasabi from seed, but best of luck to you getting your hands on them. Almost all seeds you find online are “wasabi” arugula or mustard seeds.

These plants don’t readily produce viable seeds, so real ones cost a fortune. Plus, they don’t germinate reliably, either.

That’s partially because the plants are self-incompatible. You need a male and a female to produce viable seeds. The seeds are also challenging to break out of dormancy and need pretty specific conditions to develop.

Stick to purchasing starts or dividing rhizomes.

You want loamy, rich, loose, well-draining soil regardless of which method you use. If you’re planting in the ground, make sure to work in tons and tons of well-rotted compost to make the soil as loamy, well-draining, and rich as possible.

Slightly acidic to neutral soil is best, with a pH between 6.0 and 7.0.

When it comes to selecting a container, it must have drainage holes and it should be light enough to move around. If you go with a heavy cement container, you should put it on wheels or your back will be hating you the first time the weather takes a turn.

All of the following options for propagation should be done in the spring or fall, and if you plant in the ground, provide 12 inches of space between each one.

From Nursery Transplants

You can sometimes find starts at local nurseries, depending on where you live.

If you’re in the Pacific Northwest or the Appalachian region, you may be able to find young plants at local or specialty shops. Those in places like Arizona or Wisconsin will probably have to go the online route.

Once you have your seedling, fill a large container with well-draining, loamy potting soil.

I’m always singing the praises of FoxFarm Ocean Forest potting mix, but I think it’s particularly perfect for wasabi. You don’t need to add anything. It’s just right the way it is.

Amazon carries this potting soil in 12-quart bags.

Remove the seedling from its nursery container and place it in your new pot, which needs to hold at least three gallons.

Make sure the rhizome is buried, but aim to keep the plant at the same depth as it was previously. You want the rhizome to be about half an inch below the top of the soil.

Fill in around it with potting soil and water well to settle everything. Add more soil if needed.

From Bare Roots

You can find bare root starts online. These usually include a small rhizome with a few leaves or young petioles.

You can also try planting the rhizomes you can buy at grocery stores, but they’re usually too old to sprout.

You should plant these the second you’re able to, but we all know life doesn’t make things that simple for us. Put your rhizomes in the fridge if you can’t plant them right away.

Plant each rhizome in a rich, loamy, well-draining potting soil so it is covered by about half an inch of soil. The container needs to have a capacity of three gallons or larger.

Make sure to plant the rhizome upright, with the leaves or petioles facing up. Water well and replace any settled potting soil with additional soil.

From Divisions

Once a plant is a few years old, you can pull it up and split up the rhizomes.

Keep a few for yourself to eat and separate a few to create new plants. Each rhizome, so long as it has a few nodes on it, can start a new plant.

To dig up your plant, dig around the drip line and down 18 inches. Leverage the plant out of the ground. If the plant is in a container, just remove it whole from the container.

Knock or wash away the soil and identify the rhizomes. Trim rhizomes away, taking care to include a few stems with each one, using a knife. Each one of these can develop into a new, individual plant.

Replant the rhizomes as described above for bare roots.

How to Grow Wasabi Plants

If you live somewhere with the perfect climate, go ahead and plant these directly in the ground.

Make things easier on yourself and put them in a raised bed filled with rich, loamy soil with a pH between 6.0 to 7.0.

For everyone else, plant your wasabi in containers. You WILL need to move your plants during extreme weather.

Wasabi tends to tolerate cold better than heat, so if you rarely see temps above 90°F, you’re probably fine leaving your plants in the ground.

Occasional freezes that hover above 29°F are fine, as well. If you experience more than just a few weeks of freezing temps or more than a few days at 28°F, your plant is toast.

If you have heavy snow throughout the winter, you will need to provide protection or move your plants to prevent them from being crushed.

When it comes to sun exposure, you probably want to stick to full shade. In cooler regions, you can get away with some dappled morning sun.

I find that mine grow best when provided with a little dappled sun in the morning, but the afternoon sun is an absolute killer. Or rather, your plant might survive, but the rhizome quality will be low.

Don’t forget that if you’re placing your wasabi under deciduous trees that they’ll be exposed to too much light in the winter.

Indoors, place your plants in bright but indirect light.

Yes, wasabi grows on the banks of mountain streams, but you don’t want your plants in standing water. That’s a common misconception.

If you had fresh, cold, constantly moving water as you find at the edges of a streambed, you could put your plants there, but they don’t do well at all in swampy conditions.

The amount of moisture you give arugula or lettuce? That’s what your spicy friends need.

In other words, consistently moist but not wet soil. It shouldn’t be allowed to dry out at any point. But it shouldn’t feel like a soggy mess. Aim for the consistency of a well-wrung-out sponge.

Fertilize your plants every three months with an all-purpose, mild fertilizer.

I use Down to Earth Vegetable Garden mix and I’ve had good success. I love this mix because it comes in compostable boxes and is formulated for veggies.

Down to Earth Vegetable Garden Fertilizer

Grab some for your garden at Arbico Organics. They carry one, five, or 15-pound boxes.

Growing Tips

- Keep the soil consistently moist but not wet.

- Plant in full shade or dappled morning sunlight.

- Protect plants during extreme weather.

Maintenance

There isn’t much maintenance required when growing wasabi. Divide the plants every few years as described above and replace the soil every three or four years if you’re growing in pots.

Potting soil tends to compact and leech nutrients, so it’s imperative that you refresh it regularly.

Trim away any dead or damaged leaves whenever you see them.

The mother plant will generally only have a viable lifespan of five or so years, which is why propagating root divisions is a good idea if you want to ensure an ongoing harvest.

Keep weeds away from your plants. Wasabi can’t compete and weeds act as hosts for diseases.

Pull the weeds rather than spraying them with an herbicide. Just be careful not to disturb the wasabi roots too much.

Wasabi Cultivars to Select

Here are some E. japonicum cultivars that stand out:

Daruma

‘Daruma’ is, by far, the most popular cultivar. This is the one you’re most likely to find.

That’s partially because it’s tougher than most other cultivars, tolerating hotter and colder weather. It’s also resistant to black leg and soft rot.

If you enjoy the stems, this is a good option because they’re thick, juicy, and flavorful.

The heart-shaped leaves are beautiful on an upright to spreading plant. Rhizomes are ready to harvest in about two years.

Ready to dive into the world of ‘Daruma?’ Fast Growing Trees can make your dreams a reality.

Daruma Fuji

This cultivar looks like ‘Daruma’ but it grows more quickly. The rhizomes are ready in about a year.

I’ve found it to be slightly more prone to fungal diseases, though. Unlike its cousin, it has a fully spreading growth habit.

Green Thumb

This cultivar was developed in Taiwan and is a quick grower. It also has big, impressive leaves on an upright plant.

Kamogiko 13

Resistant to soft rot, ‘Kamogiko 13’ has a spreading habit with bunches of large, heart-shaped leaves with purple petioles. The stems are flavorful and spicy.

Mazuma

This upright cultivar is the other common one that you’ll find for sale, along with ‘Daruma.’ It’s spicier than its cousin, with pretty heart-shaped leaves and purple petioles.

It isn’t as cold tolerant as ‘Daruma’ but it’s better in heat. Sadly, it’s more prone to soft rot and black leg.

The flavor is considered to be potentially some of the best, with an elegant sweetness under the heat. It takes at least two years to grow a usable rhizome and is nearly impossible to grow from seed.

Midori

‘Midori’ grows extremely fast and features lovely blue petioles. The downside is that this spreading cultivar is more prone to fungal diseases.

Misho

Ready in just a year, this cultivar resists fungal diseases. The rhizome is faintly sweet on a spreading plant.

Mochi Daruma

I’d grow this variety purely for the stems. They’re huge and flavorful with a bright green color. Sadly, this spreading type is susceptible to soft rot.

Sanpoo

Don’t grow this cultivar for the stems, which are thin and flavorless. But the tender leaves with red and white petioles are delicious.

The rhizome has an excellent flavor with medium spiciness and the spreading plant is resistant to soft rot.

Shimane 3

Don’t mistake this one for ‘Shimane Zairai,’ which is inferior in every way to ‘Shimane 3.’

The latter is resistant to fungal diseases, features good-quality stems and a pungent rhizome, and has tender leaves with reddish petioles. It has a spreading habit.

Shizukei 13

This cultivar has, hands-down, my favorite stems. They’re thick, and spicy, with sweet notes. Stir-fried with some vinegar and white pepper, you’ll be in heaven.

The rhizome is delicious, as are the young, tender leaves, which have purple petioles. It’s tolerant of soft rot and has a spreading growth habit.

Managing Pests and Disease

If you manage to nail the lighting, temperature, and soil, your next major challenge is dealing with pests and diseases.

Herbivores

Rabbits, deer, and chickens might try to snack on your plants, but only as a last resort.

One winter, the deer were making a meal out of my garden. They were eating everything, including the stuff that they typically ignored. Everything, that is, except my wasabi plants.

My chickens mostly ignored my wasabi as well. They’d occasionally try a bite and then move on to better stuff.

Since you’re probably growing your plants in containers, don’t stress about it too much. You can just create a little fence around your plants to prevent nibblers from taking a bite.

I use chicken wire and a few pieces of thick wire to create a makeshift fence in my pots.

Insects

There are a few common insects that will make a meal out of your wasabi. Some people are surprised to learn that since the plant itself has a real kick to it. Hungry insects don’t care.

Aphids

Wherever plants go, aphids go. Cabbage root (Pemphigus populitransversus), turnip (Lipaphis pseudobrassicae), green peach (Myzus persicae), and potato aphids (Macrosiphum euphorbiae) are the most common species.

We have a guide that explains how to identify and eliminate aphids.

Avoid using harsh chemicals which can both harm the plant and render the leaves inedible. Stick to spraying them with water, neem oil, or insecticidal soap.

Cabbage Worms

Some years I shake my fists impotently at the sky when I find cabbage worms on my wasabi, and other years I just sigh and get to work plucking them off.

The one thing that’s consistent is that I’ll be dealing with these little worms, and the only thing that I can change is my attitude.

Cabbage worms are the larvae of those pretty, tiny white butterflies with gray spots, known as cabbage white butterflies (Pieris rapae) you see flitting through the garden in late summer.

I used to love those butterflies until I realized what they were doing to my cole crops.

Now, when I see those butterflies flitting through the garden, I head out to my brassicas to (inevitably) find and get rid of the cabbage worms that follow.

The truth is that these worms aren’t all that bad. Not only are they probably to thank for the pungent taste of mustard and wasabi, but they don’t actually kill wasabi plants.

A massive infestation might be a problem, but if you head outside in late summer and just pluck off any worms you find, the worst of the damage is just cosmetic.

Even if you’re planning on eating the leaves, it’s the young foliage that tastes best, so it doesn’t matter if those older leaves look a bit tattered. I find these worms tend to focus on the older leaves.

I just pluck the worms off, but there are other tactics you can use like encouraging or buying natural predators or applying organic, natural products like those that contain the beneficial bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki (Btk).

Bonide Thuricide contains Btk and is highly effective against these pests.

You can pick up a quart or gallon of ready-to-use spray, or an eight- or 16-ounce concentrate, at Arbico Organics.

To learn more about figuring out if these pests are hanging out on your plants, and how to get rid of them, read our guide.

Slugs

Slugs are a major problem when the plants are young. Wasabi loves the same conditions that slugs and snails do and I’ve forgotten to keep an eye on my young plants in some years. I lost several plants to those slimy little jerks.

Luckily, as long as your plants have a few leaves left, they’re pretty good at regenerating new foliage even if they’ve been largely defoliated.

Use your favorite control techniques to keep gastropods away, or find some new ones in our guide to controlling slugs on cole crops.

Disease

There are several fungal diseases that impact wasabi, but black leg and soft rot are the most common and the most troublesome.

Breeders are working on creating more resistant plants, but in the meantime, here’s what to know:

Black Leg

The fungal disease black leg is caused by Phoma wasabiae and it is incredibly destructive. It starts with black spots all over the leaves and stems.

Then, the holes in the leaves become angular and rotten, and the veins turn dark. Eventually, the whole plant from root to tip turns mushy and black.

It’s more common in warm weather over 70°F and it tends to be more likely on older plants.

Look for brown spots with gray, fuzzy centers. The spots will expand rapidly in favorable conditions, killing off the entire leaf and, not long after, the entire plant.

Once symptoms appear, it’s too late.

There’s nothing you can do but cull the plant and toss out the soil it was growing in. Be sure to clean the container before planting wasabi or any of its relatives in there again.

If you find yourself dealing with this disease, no cultivar is totally immune, but look for resistant varieties next time to avoid the heartache.

Black Rot

Black or soft rot is a bacterial disease caused by Pectobacterium and Pseudomonas species.

The veins of the leaves on infected plants turn dark, followed by dark spots. These spots eventually turn white and the leaves turn yellow before dying.

‘Sanpoo’ and ‘Durama’ are resistant, but there is no available form of control once plants are infected. You’ll need to dispose of them.

Downy Mildew

Downy mildew is common but not terribly destructive if you catch it early.

Caused by Peronospora alliariae water molds (oomycetes), the leaves first turn pale yellowish-green before turning dark brown. A gray fuzz may develop on the undersides before leaves wilt.

It’s best controlled early and quickly.

Liquid copper fungicide spray is the best first line of attack. Use it alone or alternate it every two weeks with Fung-onil by Bonide.

This spray works against a broad range of fungi and water molds and is twice as effective when paired with copper. Pick up a 16-ounce bottle at Amazon.

Whichever you use, spray the plant thoroughly, taking care to get the top and bottom of the leaves as well as the stems. Prune away any heavily damaged leaves.

Harvesting Wasabi Roots

To harvest, gently dig up the plant and brush or wash away the soil.

Harvest any rhizomes that are at least six inches long and two inches in diameter. This should be done in the spring or fall after a good rainfall.

The ideal coloring is a medium green, but you can still eat dark green or light green rhizomes. They just tend to have an inferior flavor.

The rhizome should be tapered like a baby carrot. If it’s jagged or unevenly shaped, it’s likely that the climate conditions were highly variable throughout the season.

It doesn’t matter to us home growers, but these would be considered inferior by commercial growers.

You can pluck leaves any time of year, but the best ones are young.

Wasabi plants continue to grow new leaves throughout the year from spring until fall. Flowers appear in the early spring and you can eat them any time they’re present.

Preserving

To store the rhizome, wrap it in a damp paper towel and place it in a bag in the refrigerator.

Replace the paper towel every few days and eat the root within a few weeks. Leaves and flowers should be eaten immediately.

The rhizome can also be dried if you’re looking for ways to use up a large harvest, but keep in mind that you’ll lose a lot of that delicate flavor.

If you decide to dry it, slice the rhizome up into thin pieces and lay them flat on parchment paper. Bake in the oven on low heat until crisp.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Obviously, the rhizomes are traditionally grated on a fine, flat metal or wood grater. There are also pretty circular graters made just for grating wasabi.

I like the one made by Kinjirushi because it creates an extremely creamy texture. Snag one at Amazon.

More traditionally, wasabi root is grated into a paste using a samekawa-oroshi, which is a piece of wood covered in sharkskin to create a rough surface.

Grate up a bit and spoon it onto your plate. The paste should be eaten right away. As soon as you grate it, it starts to lose flavor.

If you want to use the wasabi in the traditional manner, you should dab it between the fish and the rice as you’re making your nigiri. You need a bit more paste with extremely fatty fish like fatty tuna or pungent fish like mackerel, and less with more subtly flavored fish.

You don’t need to add additional wasabi when you eat your nigiri unless you really want to.

If you want to add more, don’t mix it with soy sauce, just add a dab with your chopstick. (And don’t dip the rice side in your soy sauce! Dip the fish side.) You can take a small bit of wasabi and place it on sashimi before dipping it into your soy sauce as well.

If I hear that you’ve been mixing your fresh wasabi with your soy sauce, I might cry.

I think it’s perfectly fine to do this with the horseradish stuff, even though it isn’t how they do it in traditional sushi restaurants, but you’ve gone to all the trouble of growing this challenging plant. Don’t ruin the delicate flavor by mixing it with soy sauce.

If you only ever use your paste with raw fish or tataki (marinated beef), you already have a fantastic ingredient that doesn’t need to be put to use anywhere else.

But you can use it in so many other ways! And now that you aren’t paying extraordinary prices for a few ounces, you can afford to experiment.

Oregon Coast Wasabi has an excellent recipe for mint gazpacho that combines mint leaves, wasabi paste, chopped cucumber, lemon, garlic, olive oil, and salt.

I like to use the paste to make hummus and deviled eggs, while my husband uses it to make some killer bloody mary cocktails with the stems and leaves as a garnish.

Use the leaves on salads or to make pesto in place of basil leaves. They’re also tasty on sandwiches or chopped and added as a garnish to soup.

Surprise twist: wasabi and chocolate go together extremely well! One year I had more rhizomes than I knew what to do with, so I chopped up and crystalized a rhizome as you would ginger and added it to gooey chocolate cookies. To die for.

You can find instructions for crystallizing ginger on our sister site, Foodal.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Herbaceous perennial vegetable | Flower/Foliage Color: | White/green |

| Native to: | Japan, Russia, South Korea | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 8-10 | Tolerance | Excess moisture |

| Bloom Time: | Spring/evergreen | Soil Type: | Loamy, rich |

| Exposure: | Shade or dappled morning sun | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | 1-2 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 12 inches | Attracts: | Bees |

| Planting Depth: | 1/2 inch (rhizome) | Companion Planting: | Hostas, ferns |

| Height: | 2 feet | Avoid Planting With: | Other cole crops |

| Spread: | 2 feet | Order: | Brassicales |

| Growth Rate: | Fast | Family: | Brassicaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate to high | Genus: | Eutrema |

| Common Pests and Disease: | Aphids, cabbage worms, deer, rabbits, slugs, snails; black leg, downy mildew, soft rot | Species: | Japonicum syn. japonica |

Make Mine Spicy

I was plucking cabbage white worms off my wasabi plants the other day and I thought to myself, you know? I wouldn’t give these plants up despite their fussy nature, or even if you could buy cheap leaves and roots at any old grocery store.

It’s not just that they’re beautiful, though they are, but there’s a lot to be said for a gardening challenge. When it all goes well, it’s delightful, but it can still be rewarding even when it all goes wrong.

I haven’t gone so far as to name my plants yet, but I’ve definitely developed a relationship with them. Any suggestions for naming them?

While we’re at it, do you have any great recipe ideas? I mean, you’re going to be flush with rhizomes soon, so you’d better be thinking ahead, and I’m always up for some tasty ideas. Share them in the comments.

If you want to grow some of wasabi’s less difficult brassica cousins, we can help with that. Here are a few guides worth checking out. Just remember not to plant them too close to your wasabi or you’ll encourage pests and diseases.